Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Columbus, Mississippi

Overview >> Mississippi >> Columbus

Historical Overview

|

Located along the Tombigbee River, Columbus, Mississippi, is the seat of Lowndes County in the northeastern part of the state. Euro-American settlers and enslaved African Americans began moving to the area in large numbers during the 1830s, after treaties between the United States and the Choctaw and Chickasaw Nations initiated Indian Removal and opened the Black Prairie area for settlement.

By 1840 the population of Lowndes County had swelled to more than 14,000 people, including 8,700 enslaved Black workers. Local agricultural production boomed due to both the fertile land and the forced labor of the majority Black workforce. Columbus developed into the area’s main commercial hub and soon attracted a handful of Jewish migrants. Most Jewish men initially earned their living as peddlers, carrying goods in wagons in order to sell in nearby rural areas, and some of these early peddlers later opened their own stores. Jews became an active part of the community, from joining the Confederate war effort during the Civil War—when the Confederate Army housed an arsenal in Columbus—to developing commerce in the 19th and 20th centuries. Organized Jewish Life

|

Archie Bernstein in front of Ruth's Department Store, which he founded in 1940. Photo by Bill Aron. c. 1990.

Archie Bernstein in front of Ruth's Department Store, which he founded in 1940. Photo by Bill Aron. c. 1990.

Jewish Columbus residents began praying together during the 1840s, but it took several decades for them to organize community institutions. Rather than buying their own cemetery, they purchased a separate section in Columbus’s Friendship Cemetery in 1850. In 1871 they founded a local chapter of B’nai B’rith. According to an 1877 report published in the national Jewish newspaper the American Israelite, the presence of “cliques” among the Columbus Jewish community impeded the founding of a congregation, despite the presence of “sufficient people” and “sufficient means” to do so.

Columbus Jews established a Sunday school that year, however, and began the process of organizing a congregation in 1878. The following year they founded B’nai Israel (Children of Israel), and I. Bluhm served as the congregation’s first president. The board of B’nai Israel included a finance committee whose purpose was to raise contributions from larger Jewish communities in the East—a common source of monetary support for “frontier” Jewish congregations in the 19th century.

From its founding, B’nai Israel was Reform in practice, although it did not join the Union of American Hebrew Congregations (the national organization of Reform Judaism) until well into the 20th century. In its early years, B’nai Israel charted its own course of religious practice, distinct from both classical Reform Judaism and from traditional observance. From their founding, B’nai Israel adopted Isaac Mayer Wise’s “Minhag America” as their mode of worship. Not long after they formed, they hired Joseph Herz as rabbi at a salary of $25 a month. They also hired a music and choir director and purchased an organ. An early board motion passed requiring the rabbi to wear a kippah, but the board voted down a motion that would have required him to wear a tallit.

The young congregation rented a building from the local Odd Fellows society, which they used as their house of worship for almost thirty years. In 1880 they dedicated the synagogue space at a public ceremony attended by congregants, elected officials, clergy, and press. Soon after, B’nai Israel had 39 members, though there were several Columbus Jews who had not joined the congregation. Most of these unaffiliated were young men without spouses or families; non-members were charged $2.00 for seats at High Holiday services. In 1882, Jewish women formed the Ladies’ Hebrew Benevolent Association of Columbus. Mrs. T. Loeb served as president, Mrs. L. Weiman, vice-president and Mrs. L. Fleishman, secretary.

During its early years, B’nai Israel experienced economic hardship. The congregation cut its dues to attract new members, created a “detailed account” of all congregants in arrears, and suspended those with outstanding debts. In June of 1884, B’nai Israel raffled off a clock in an attempt to raise money, and in 1885 the congregation was forced to reduce the rabbi’s salary from $400 to $300 a year.

Columbus Jews established a Sunday school that year, however, and began the process of organizing a congregation in 1878. The following year they founded B’nai Israel (Children of Israel), and I. Bluhm served as the congregation’s first president. The board of B’nai Israel included a finance committee whose purpose was to raise contributions from larger Jewish communities in the East—a common source of monetary support for “frontier” Jewish congregations in the 19th century.

From its founding, B’nai Israel was Reform in practice, although it did not join the Union of American Hebrew Congregations (the national organization of Reform Judaism) until well into the 20th century. In its early years, B’nai Israel charted its own course of religious practice, distinct from both classical Reform Judaism and from traditional observance. From their founding, B’nai Israel adopted Isaac Mayer Wise’s “Minhag America” as their mode of worship. Not long after they formed, they hired Joseph Herz as rabbi at a salary of $25 a month. They also hired a music and choir director and purchased an organ. An early board motion passed requiring the rabbi to wear a kippah, but the board voted down a motion that would have required him to wear a tallit.

The young congregation rented a building from the local Odd Fellows society, which they used as their house of worship for almost thirty years. In 1880 they dedicated the synagogue space at a public ceremony attended by congregants, elected officials, clergy, and press. Soon after, B’nai Israel had 39 members, though there were several Columbus Jews who had not joined the congregation. Most of these unaffiliated were young men without spouses or families; non-members were charged $2.00 for seats at High Holiday services. In 1882, Jewish women formed the Ladies’ Hebrew Benevolent Association of Columbus. Mrs. T. Loeb served as president, Mrs. L. Weiman, vice-president and Mrs. L. Fleishman, secretary.

During its early years, B’nai Israel experienced economic hardship. The congregation cut its dues to attract new members, created a “detailed account” of all congregants in arrears, and suspended those with outstanding debts. In June of 1884, B’nai Israel raffled off a clock in an attempt to raise money, and in 1885 the congregation was forced to reduce the rabbi’s salary from $400 to $300 a year.

Business and Civic Life

For the most part, Jews felt welcome in Columbus, but they did face anti-Jewish sentiments. In 1875, an anonymous writer criticized Columbus’ Jewish population in the local newspaper, claiming that they were “clannish” and “housed up like the terrapin within his shell” in both social and economic affairs. He also accused Jews of not buying real estate (thus avoiding local property taxes) and buying their merchandise in other cities rather than patronizing local gentile-owned stores.

A Columbus Jew responded to these charges in the American Israelite, a national Jewish newspaper published in Cincinnati. He argued that the social exclusion started with the town’s gentiles, writing, “you will not admit the Jew to your home circle; your wives and daughters will not meet their’s on a footing of equality.” He also explained that many of the town’s Jews were young and recently arrived in the United States, so they did not have the means to purchase property and found renting to be more economically advantageous. As for not shopping in Columbus’s stores, he claimed that local shops catered to local tastes that these Jewish immigrants did not share, writing that Jews were, “not accustomed to an unvarying diet of bacon and corn meal” and appreciated “other luxuries in life than whiskey and tobacco.”

This remarkable exchange shows that Columbus Jews were not well integrated into local (white) society in the 1870s. But the Jewish writer mentioned the means through which they would gain acceptance in town when he wrote that Jews were “the backbone of Southern commerce, and as necessary to it as steam or iron.” Indeed, Jewish merchants played integral roles as Columbus and the rest of the South reemerged following the economic upheavals of the Civil War and the abolition of the slavery.

A Columbus Jew responded to these charges in the American Israelite, a national Jewish newspaper published in Cincinnati. He argued that the social exclusion started with the town’s gentiles, writing, “you will not admit the Jew to your home circle; your wives and daughters will not meet their’s on a footing of equality.” He also explained that many of the town’s Jews were young and recently arrived in the United States, so they did not have the means to purchase property and found renting to be more economically advantageous. As for not shopping in Columbus’s stores, he claimed that local shops catered to local tastes that these Jewish immigrants did not share, writing that Jews were, “not accustomed to an unvarying diet of bacon and corn meal” and appreciated “other luxuries in life than whiskey and tobacco.”

This remarkable exchange shows that Columbus Jews were not well integrated into local (white) society in the 1870s. But the Jewish writer mentioned the means through which they would gain acceptance in town when he wrote that Jews were “the backbone of Southern commerce, and as necessary to it as steam or iron.” Indeed, Jewish merchants played integral roles as Columbus and the rest of the South reemerged following the economic upheavals of the Civil War and the abolition of the slavery.

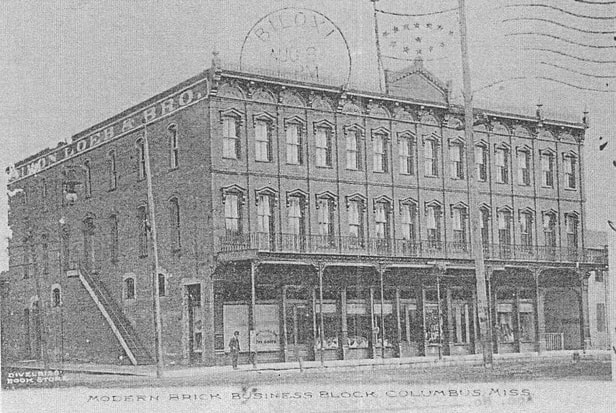

By the early 20th century Jewish stores occupied a central role in local commercial life. The 1912 city directory lists three businesses for clothing retail, two of which were run by Jewish families. Jews also owned nearly half of the dry goods stores that appear in the 1912 directory. The Kaufman Brothers store, founded in 1896, included both a retail and wholesale operation. The store’s owners were the three sons of Herman Kaufman, a German speaking Jewish immigrant who had served in the Mississippi Infantry during the Civil War. After the war Kaufman worked for another Jewish retail firm, Simon Loeb and Brothers. (In the early days of B’nai Israel, the congregation held Sunday school at the Loeb store.) The Loeb family business lasted well into the 20th century, and the Kaufman Brothers store remained successful until 1931, when a catastrophic fire destroyed $65,000 of merchandise and forced the business to close.

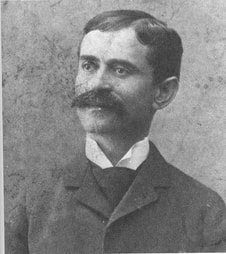

Simon Loeb

Simon Loeb

Jewish success in retail led to opportunities for civic leadership. Sidney Loeb was vice president of the local Chamber of Commerce, a founder of the Columbus Rotary Club, and on the board of the First National Bank of Columbus. Edna Loeb, the daughter of Simon Loeb, became the first female attorney in Lowndes County, passing the bar in 1936. Irvin Kaufman served as president of the Columbus Athletic Association and was later asked to serve on the board of the Y.M.C.A. When Columbus celebrated its 100th anniversary in 1921, Kaufman served on the executive committee. He was also a longtime leader of the local Elks Club. Morris Goldstein was involved in the local Masonic Lodge and the Chamber of Commerce.

In addition to their secular fraternal activities, Columbus Jews were active in B’nai B’rith. The local lodge raised money for Jewish causes around the country, including the National Jewish Hospital in Denver, the Jewish Orphanage in New Orleans, and the Hebrew Sheltering and Immigrant Aid Society. The lodge also provided death benefits to the dependents of deceased members. They renamed the lodge after Joseph Herz, the longtime rabbi of B’nai Israel who died in 1909. The lodge had many members from the small towns outside of Columbus, such as West Point, Tupelo, Booneville, New Albany, and Pontotoc.

In addition to their secular fraternal activities, Columbus Jews were active in B’nai B’rith. The local lodge raised money for Jewish causes around the country, including the National Jewish Hospital in Denver, the Jewish Orphanage in New Orleans, and the Hebrew Sheltering and Immigrant Aid Society. The lodge also provided death benefits to the dependents of deceased members. They renamed the lodge after Joseph Herz, the longtime rabbi of B’nai Israel who died in 1909. The lodge had many members from the small towns outside of Columbus, such as West Point, Tupelo, Booneville, New Albany, and Pontotoc.

B’nai Israel in the Early 20th Century

As early as 1891, congregants began to raise money for the construction of a larger synagogue. Because of their small size and the high rate of turnover, however, B’nai Israel was not able to purchase or build a building of their own for more than a decade. In 1897 the congregation had shrunk to only 15 households, and the board began to recruit members from such neighboring towns as Starkville, West Point, Aberdeen, and Macon. In 1904 a group of Jews in Aberdeen successfully organized and petitioned B’nai Israel to join the congregation. B’nai Israel thus became a regional congregation, and it continues to draw Jewish residents of nearby towns in the early 21st century.

The congregation persisted in raising funds for a new house of worship. They even solicited and received a $100 donation from New York financier Jacob Schiff. At the 1906 annual meeting, congregation president Simon Loeb exhorted members to “stand up for their religion and put their shoulders to the wheel” in the fundraising effort. In 1906, when the congregation was without a space to hold services, several local churches offered B’nai Israel free use of their facilities. B’nai Israel accepted the kind offer of the Christian Church, and donated a new carpet to the church as thanks for their generosity. In December of 1906 the congregation voted to purchase an old building in town for use as a temple. Built in 1844 as a Methodist Church, the building had been a military hospital during the Civil War, a private military school, a city gymnasium, and a community concert hall. Upon purchasing the building for $2,400, the congregation began a program of renovations, transforming the former church into the synagogue that would house them for the next 53 years.

Rabbi Brill of Greenville led the dedication service in 1908. In a description of the dedication one author credited the “untiring efforts and devoted loyalty,” of the ladies of the congregation for ensuring its completion. At the time, the congregation numbered over 200 families. When Rabbi Joseph Herz died a year later, he had served as the B’nai Israel rabbi for 28 years. Rabbi Herz was well loved by the congregation, who recognized his potential early on. In 1883, one congregant described him as “a promising young man who labors faithfully in the ranks of Judaism.”

After Rabbi Herz’s death, Sol Schwab, a B’nai Israel member and dry goods merchant, served as spiritual leader of the congregation. For years, the congregation functioned with lay leaders rather than an ordained rabbi. In 1939 they hired Rabbi Bernard Adler. The congregation’s membership and financial means had declined during the Great Depression, however, and they were unable to maintain the expense of a full-time rabbi. He left in 1940, and the congregation hired visiting rabbis to lead services on a monthly basis.

The congregation persisted in raising funds for a new house of worship. They even solicited and received a $100 donation from New York financier Jacob Schiff. At the 1906 annual meeting, congregation president Simon Loeb exhorted members to “stand up for their religion and put their shoulders to the wheel” in the fundraising effort. In 1906, when the congregation was without a space to hold services, several local churches offered B’nai Israel free use of their facilities. B’nai Israel accepted the kind offer of the Christian Church, and donated a new carpet to the church as thanks for their generosity. In December of 1906 the congregation voted to purchase an old building in town for use as a temple. Built in 1844 as a Methodist Church, the building had been a military hospital during the Civil War, a private military school, a city gymnasium, and a community concert hall. Upon purchasing the building for $2,400, the congregation began a program of renovations, transforming the former church into the synagogue that would house them for the next 53 years.

Rabbi Brill of Greenville led the dedication service in 1908. In a description of the dedication one author credited the “untiring efforts and devoted loyalty,” of the ladies of the congregation for ensuring its completion. At the time, the congregation numbered over 200 families. When Rabbi Joseph Herz died a year later, he had served as the B’nai Israel rabbi for 28 years. Rabbi Herz was well loved by the congregation, who recognized his potential early on. In 1883, one congregant described him as “a promising young man who labors faithfully in the ranks of Judaism.”

After Rabbi Herz’s death, Sol Schwab, a B’nai Israel member and dry goods merchant, served as spiritual leader of the congregation. For years, the congregation functioned with lay leaders rather than an ordained rabbi. In 1939 they hired Rabbi Bernard Adler. The congregation’s membership and financial means had declined during the Great Depression, however, and they were unable to maintain the expense of a full-time rabbi. He left in 1940, and the congregation hired visiting rabbis to lead services on a monthly basis.

World War II and the Post-War Era

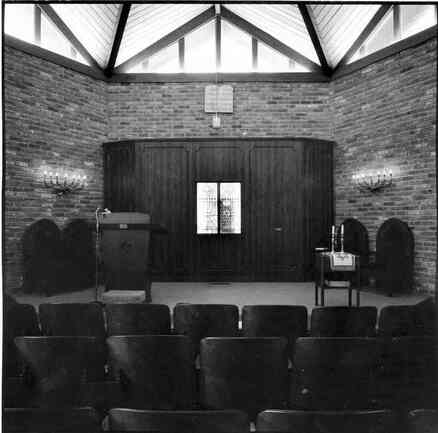

Exterior of the B'nai Israel synagogue, built in 1960. Photo by Bill Aron.

Exterior of the B'nai Israel synagogue, built in 1960. Photo by Bill Aron.

The opening of an Air Force base in Columbus in 1942 brought new prosperity to the congregation. Columbus Jews were closely involved in the town’s commerce, owning seven retail stores, a shoe shop, two theaters, an insurance agency, and a garment plant that employed over 1,000 people. As a result, the influx of over 8,000 troops to the area proved especially beneficial to the Jewish community. B’nai Israel’s recurring problem with congregants in arrears vanished, as years of unpaid dues came pouring into the synagogue. The treasury balance grew from a paltry $13 in November of 1941 to over $3,000 in March of 1946. They were now able to afford a full-time rabbi and hired J. Spear for the position. B’nai Israel also took the opportunity to revamp its temple building and purchase new sets of prayer books. The congregation also threw its support behind the Zionist movement. Efforts to support Jewish settlement in Palestine and the emergent state of Israel included food drives for settlers held in 1946 and 1947.

The Air Force base also brought in new worshippers over the years. The Columbus Jewish community welcomed Jewish military personnel to the synagogue, and the local B’nai B’rith lodge reached out to Jews who were stationed at the base. That tradition continued into the 21st century; a 2002-2003 congregational brochure notes that “Air Force personnel and their children are welcome at all events and occasions” and “no dues are charged.”

In decades after World War II Jews continued to play prominent roles in local communities. In nearby Starkville, Henry Mayer owned and edited The Starkville News for many years. Popular Jewish retail shops in Columbus included the Globe, a men’s clothing store founded by Archie Gordon and later run by his son Leon, and Ruth’s Department Store, owned by Archie Bernstein.

Congregational life underwent a series of changes in the postwar era. B’nai Israel fired an unpopular rabbi in 1946. The following year they hired Dr. Louis Kuppin, who served the congregation until 1962. Rabbi Kuppin also taught in the music department at the Mississippi State College for Women, located in Columbus. Following his retirement B’nai Israel began to employ visiting student rabbis from Hebrew Union College.

During Rabbi Kuppin’s tenure the congregation’s synagogue building became a financial burden, due to the need for constant repairs. In 1960 members voted to tear down the aging building and to rebuild a smaller structure on the same site. Bricks from the old temple were used in the new construction. While the new home was being built, B’nai Israel held services at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, reflecting the close ties between B’nai Israel and the town’s Christian population.

B’nai Israel remained a small but active community during the late 20th century. In 1961 the first confirmation ceremony to take place in the new synagogue honored five students: Paul Rechtman, Michael Kleban, Marcia Lasky, David Smith, and Rachel Ann Berman. Karen Katz became bat mitzvah in 1968—the first such ceremony in the new building—and there was not a bar mitzvah ceremony in the synagogue until 1980, when Gregg Adam Fine came of age.

The Air Force base also brought in new worshippers over the years. The Columbus Jewish community welcomed Jewish military personnel to the synagogue, and the local B’nai B’rith lodge reached out to Jews who were stationed at the base. That tradition continued into the 21st century; a 2002-2003 congregational brochure notes that “Air Force personnel and their children are welcome at all events and occasions” and “no dues are charged.”

In decades after World War II Jews continued to play prominent roles in local communities. In nearby Starkville, Henry Mayer owned and edited The Starkville News for many years. Popular Jewish retail shops in Columbus included the Globe, a men’s clothing store founded by Archie Gordon and later run by his son Leon, and Ruth’s Department Store, owned by Archie Bernstein.

Congregational life underwent a series of changes in the postwar era. B’nai Israel fired an unpopular rabbi in 1946. The following year they hired Dr. Louis Kuppin, who served the congregation until 1962. Rabbi Kuppin also taught in the music department at the Mississippi State College for Women, located in Columbus. Following his retirement B’nai Israel began to employ visiting student rabbis from Hebrew Union College.

During Rabbi Kuppin’s tenure the congregation’s synagogue building became a financial burden, due to the need for constant repairs. In 1960 members voted to tear down the aging building and to rebuild a smaller structure on the same site. Bricks from the old temple were used in the new construction. While the new home was being built, B’nai Israel held services at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, reflecting the close ties between B’nai Israel and the town’s Christian population.

B’nai Israel remained a small but active community during the late 20th century. In 1961 the first confirmation ceremony to take place in the new synagogue honored five students: Paul Rechtman, Michael Kleban, Marcia Lasky, David Smith, and Rachel Ann Berman. Karen Katz became bat mitzvah in 1968—the first such ceremony in the new building—and there was not a bar mitzvah ceremony in the synagogue until 1980, when Gregg Adam Fine came of age.

The Jewish Community in Columbus Today

As of 2020 Columbus’s B’nai Israel remains a hub for Jews in the “Golden Triangle” of Mississippi—Starkville, Aberdeen, West Point, and Columbus—and in western Alabama. The congregation holds regular services (including online Shabbat services during the COVID-19 pandemic), which are conducted by Rabbi Seth Oppenheimer. Rabbi Oppenheimer is a professor and administrator at Mississippi State University in Starkville and served the congregation as a lay leader for many years before receiving his official ordination in 2019. His affiliation with Mississippi State reflects a general trend in the area’s Jewish community, as many of the congregation’s 15-20 members now live and work in Starkville.