Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Treasure Coast, FL

Overview

Florida’s Treasure Coast includes (from north to south) Indian River, St. Lucie, and Martin Counties. It is bordered to the north by Brevard County and the Space Coast and to the south by Palm Beach County. Like other small communities on the Atlantic Coast, the area’s Jewish population first consisted of a few families who owned department stores and small businesses. Fort Pierce in St. Lucie County attracted the majority of early Jewish settlers, and they started the area’s first synagogue there in 1948. Over subsequent decades the area’s Jewish population grew due to the rise of retirement communities and a thriving tourism industry, and Port St. Lucie and Stuart—in St. Lucie and Martin Counties, respectively—now serve as the largest centers of Jewish life on the Treasure Coast.

Early Jewish Settlement

The Treasure Coast remained sparsely populated well into the twentieth century, but small towns developed as market hubs for nearby fishing villages and citrus orchards. While there may have been other Jews in the area prior to 1910, the first known Jewish family on the Treasure Coast were Isadore and Sara Holtsberg. According to family history, they lived in New York City during the 1890s, when Isadore left Sara and their children to seek a fortune in the Klondike gold rush. He returned without striking it rich, however, and the family remained in New York until around 1910, when they relocated to Jensen, Florida, across the St. Lucie River from Stuart in Martin County. By 1912, the Holtsbergs and their younger children had settled in Fort Pierce, where they opened a department store on Second Street. Their adult son Fred followed not long after and started a grocery business that delivered goods by rowboat up and down the coast.

Brothers Morris, Isadore, and Ralph Rubin, 1967. Isadore Rubin lived for a time in Cocoa and was the son-in-law of Sara and Isadore Holtsberg, and his brother Ralph bought the Holtsberg Department Store in 1928. State Archives of Florida.

Brothers Morris, Isadore, and Ralph Rubin, 1967. Isadore Rubin lived for a time in Cocoa and was the son-in-law of Sara and Isadore Holtsberg, and his brother Ralph bought the Holtsberg Department Store in 1928. State Archives of Florida.

The arrival of the Holtsbergs brought other Jews to the area. First, their daughter Anna and her husband Isadore Rubin settled up the coast in Cocoa around 1914. After Isadore Holtsberg died in 1921, Sara ran the Holtsberg Department Store in Fort Pierce until 1928, when she sold it to Ralph Rubin, Anna Holtsberg Rubin’s brother-in-law. The Rubin family operated the store as Rubin Brothers for decades. Both the Holtsberg and Rubin families received a warm welcome in Fort Pierce, and they became popular civic and business leaders. This early success set the tone for Jewish acceptance among the broader community in coming years.

While the Holtsberg and Rubin families may have been the first Jews to settle permanently in the Treasure Coast region, others followed suit by 1930 or so. Louis Miller, a Jewish immigrant from Russia, lived with his family in St. Pierce and sold real estate in the late 1920s. The family relocated by 1935, however, and it is not clear if they were involved in Jewish life. In 1925, Nathan Zelmenovitz moved to Okeechobee (inland from Port St. Lucie in Okeechobee County), where he operated a cattle ranch. Several later members of the local Jewish congregation arrived in Fort Pierce between 1930 and 1935, including Ben and Gerri Duke and George and Sybil Gilbert.

While the Holtsberg and Rubin families may have been the first Jews to settle permanently in the Treasure Coast region, others followed suit by 1930 or so. Louis Miller, a Jewish immigrant from Russia, lived with his family in St. Pierce and sold real estate in the late 1920s. The family relocated by 1935, however, and it is not clear if they were involved in Jewish life. In 1925, Nathan Zelmenovitz moved to Okeechobee (inland from Port St. Lucie in Okeechobee County), where he operated a cattle ranch. Several later members of the local Jewish congregation arrived in Fort Pierce between 1930 and 1935, including Ben and Gerri Duke and George and Sybil Gilbert.

Organized Jewish Life

Like many other parts of Florida, the Treasure Coast served as a military training ground during World War II. The influx of service members and military construction spurred development in the area, which had been home to about 27 thousand residents in 1940, split between Indian River, St. Lucie, and Martin Counties. In the absence of local Jewish communal institutions, the Rubin family opened their home for social events and religious services with Jewish military personnel.

By the end of the 1940s, the small Jewish community had grown large enough to establish its own congregation, spurred in part by the arrival of a retired rabbi, Menachem “Uncle Jack” Freedman. When Freedman arrived in Fort Pierce in 1948 to open Uncle Jack’s Pawn Shop, he expressed “dismay” that there was no synagogue. Freedman quickly organized weekly Friday-night services held at the Women’s Club in Fort Pierce. By High Holy Days of that year, local Jews gathered for services in a Methodist church, where they decided to found Temple Beth El and establish a building fund for the construction of a synagogue.

At the time of Temple Beth El’s founding, the congregation reportedly drew 22 Jewish families—17 from Fort Pierce, one from Vero Beach, three from Stuart, and one from Okeechobee. Ben and Gerri Duke donated a small plot of land on 23rd Street for a synagogue, and the congregation began construction on a building in the spring of 1949. The project reportedly cost $13,500, and more than 10% of that sum came from non-Jewish donors. The modest synagogue featured “an assortment of seats and no air conditioning” for its first High Holiday services, and the congregation had to close the windows after their small choir drew the accompaniment of a rooster and several chickens from the barnyard nextdoor. In the early 1950s, Fort Pierce newcomers Meyer and Dorothy Heller made a large donation that allowed Temple Beth El to add a social hall and install air conditioning. In later years the congregation published an annual souvenir yearbook that helped to fund the addition of classrooms, an administrative office, and a rabbi’s study.

At the time of Temple Beth El’s founding, the congregation reportedly drew 22 Jewish families—17 from Fort Pierce, one from Vero Beach, three from Stuart, and one from Okeechobee. Ben and Gerri Duke donated a small plot of land on 23rd Street for a synagogue, and the congregation began construction on a building in the spring of 1949. The project reportedly cost $13,500, and more than 10% of that sum came from non-Jewish donors. The modest synagogue featured “an assortment of seats and no air conditioning” for its first High Holiday services, and the congregation had to close the windows after their small choir drew the accompaniment of a rooster and several chickens from the barnyard nextdoor. In the early 1950s, Fort Pierce newcomers Meyer and Dorothy Heller made a large donation that allowed Temple Beth El to add a social hall and install air conditioning. In later years the congregation published an annual souvenir yearbook that helped to fund the addition of classrooms, an administrative office, and a rabbi’s study.

Civic and Social Life

Nathan Zelmenovitz served as the state representative for Okeechobee County in the 1950s before relocating to Fort Pierce. State Archives of Florida.

Nathan Zelmenovitz served as the state representative for Okeechobee County in the 1950s before relocating to Fort Pierce. State Archives of Florida.

Newspaper articles and congregational histories emphasize the local Jewish community’s acceptance among the broader population. The Rubin Bros. store, formerly Holtsberg’s Department Store, was a popular retail establishment, and the family earned further good will by extending credit to their customers during the Great Depression. Fred Holtsberg left the grocery business in the 1930s and bought an orange grove north of Vero Beach. He continued to live in Fort Pierce, however, and was elected mayor in 1938. As mayor, Holtsberg helped pass an ordinance against public mask wearing by the Ku Klux Klan. Ralph and Ida Rubin’s son Bernard also served as mayor from 1956 to 1958. Their other son, Arthur, ran the family store until 1987 and served as a leader of several local civic groups. Menachem Freedman also developed a reputation as one of the better clergy in the Fort Pierce area, and non-Jews reportedly attended Temple Beth El on occasion to hear his sermons.

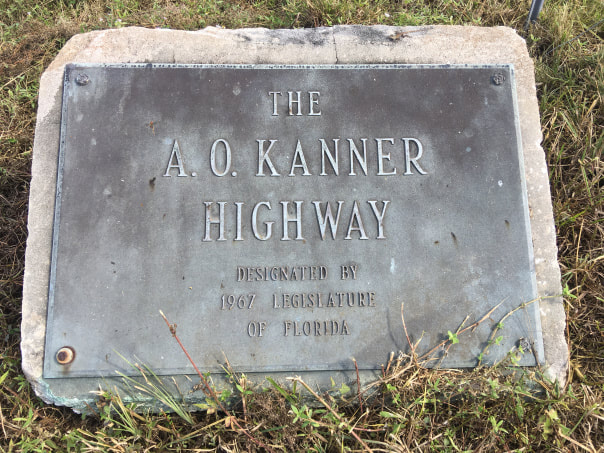

Stuart also boasted a prominent Jewish politician: Judge Abram Otto (A. O.) Kanner. The Sanford native moved to Stuart in 1925, when the town became the seat of newly formed Martin County. He had previously worked as an attorney in Jacksonville and, along with law partner Edward Joseph Smith, was a friend and supporter of Jacksonville Mayor and Florida Governor John W. Martin, namesake of Martin County. When the state created Martin County after John Martin’s election to governor in 1925, Governor Martin appointed Kanner and Smith to judgeships in Stuart. Over the years Kanner served in a number of appointed and elected positions, including state circuit judge, state representative and senator, and federal judge. A state road was named in Kanner’s honor following his death in 1967. The town of Stuart elected another Jewish resident, department store owner Irving Kanarek, as mayor in 1954. Kanarek's son Paul served for many years as a 19th Circuit Judge based in Vero Beach.

While Jewish families made their marks as civic and political leaders in Fort Pierce and Stuart, Nathan Zelmenovitz became a popular figure in Okeechobee. The Georgia native and was known as a leader in the cattle industry for decades before winning election to the Florida legislature as a representative for Okeechobee County in 1952. He also helped to build a hospital and community swimming pool in Okeechobee, as well as donating the building that served as the city’s first public library. After three terms as a state congressman, he relocated to Fort Pierce, where he quickly became involved in local civic groups, especially as head of the Fort Pierce Housing Authority.

Stuart also boasted a prominent Jewish politician: Judge Abram Otto (A. O.) Kanner. The Sanford native moved to Stuart in 1925, when the town became the seat of newly formed Martin County. He had previously worked as an attorney in Jacksonville and, along with law partner Edward Joseph Smith, was a friend and supporter of Jacksonville Mayor and Florida Governor John W. Martin, namesake of Martin County. When the state created Martin County after John Martin’s election to governor in 1925, Governor Martin appointed Kanner and Smith to judgeships in Stuart. Over the years Kanner served in a number of appointed and elected positions, including state circuit judge, state representative and senator, and federal judge. A state road was named in Kanner’s honor following his death in 1967. The town of Stuart elected another Jewish resident, department store owner Irving Kanarek, as mayor in 1954. Kanarek's son Paul served for many years as a 19th Circuit Judge based in Vero Beach.

While Jewish families made their marks as civic and political leaders in Fort Pierce and Stuart, Nathan Zelmenovitz became a popular figure in Okeechobee. The Georgia native and was known as a leader in the cattle industry for decades before winning election to the Florida legislature as a representative for Okeechobee County in 1952. He also helped to build a hospital and community swimming pool in Okeechobee, as well as donating the building that served as the city’s first public library. After three terms as a state congressman, he relocated to Fort Pierce, where he quickly became involved in local civic groups, especially as head of the Fort Pierce Housing Authority.

Jewish Growth

Temple Beth El remained the only Jewish congregation on the Treasure Coast for several decades, which required the synagogue to balance the needs and preferences of members from a variety of denominational backgrounds. The congregation identified as Reform from its founding, however. Rabbi Louis Schecter, who had previously served an Orthodox congregation in Louisville, joined Temple Beth El in 1953 as its first full-time rabbi. He only stayed in Fort Pierce for a two years or so, at which point Rabbi Freedman and other congregants once again took over religious leadership. Beginning in 1960, Temple Beth El began to hire Reform rabbis, a series of which served the congregation for four- and five-year terms until the 1980s.

Despite expansions, the original Temple Beth El building grew too small for the congregation during the 1970s. A 1975 newspaper notice asked High Holiday service attendees to contact the congregation in advance “since limited seating will be available.” They sold the building to a local church in the late 1970s and soon built a new synagogue in White City, an unincorporated area south of Fort Pierce. The relocation seems to have motivated Jewish families in Vero Beach (to the north in Indian River County) to establish their own synagogue, as the new site required a longer drive. They founded Temple Beth Shalom (Reform) in 1979 and initially used rented spaces to hold services.

Despite expansions, the original Temple Beth El building grew too small for the congregation during the 1970s. A 1975 newspaper notice asked High Holiday service attendees to contact the congregation in advance “since limited seating will be available.” They sold the building to a local church in the late 1970s and soon built a new synagogue in White City, an unincorporated area south of Fort Pierce. The relocation seems to have motivated Jewish families in Vero Beach (to the north in Indian River County) to establish their own synagogue, as the new site required a longer drive. They founded Temple Beth Shalom (Reform) in 1979 and initially used rented spaces to hold services.

As Temple Beth El prepared for its first move, the Treasure Coast experienced a period of rapid population growth among both the general and Jewish populations. While an estimated 200 Jews lived in the area as of 1970, that figure rose to more than 2,500 by the mid-1980s. Many of the newcomers—especially retirees from the Northeast and from Greater Miami—settled in the general area of Port St. Lucie. Temple Beth El’s southward move reflected this shift in the geographical center of the local Jewish population, as did the emergence of new congregations in the 1980s: Congregation Beth Abraham (Conservative) in Port Salerno and Temple Israel (Reform) in Port St. Lucie. Temple Beth Shalom of Vero Beach also grew during the early and mid-1980s, reaching 110 families in 1985. Temple Beth El reported 150 member families at that time, and Congregation Beth Abraham (operated out of the Treasure Coast Jewish Center) claimed 66 households in 1983.

Late 20th and 21st Centuries

Community histories and newspaper articles about Jewish life on the Treasure Coast tend to emphasize Jews’ acceptance among the general population, but the area could also be home to alarming anti-Semitic undercurrents. In the late 1980s a prominent racist skinhead organizer lived in Fort Pierce, contributing to an increased threat of anti-Jewish actions. In May 1990 unidentified vandals desecrated the buildings of both Temple Beth El and Temple Beth Israel with spraypainted swastikas and anti-Semitic slogans. The culprits were never arrested, and white nationalist groups, including neo Nazis and the Ku Klux Klan, continued to operate visibly in the Treasure Coast and other areas of Florida through the mid-1990s.

Despite moments of turbulence, Jewish life in Indian River, St. Lucie, and Martin Counties continued. At the southern end of the Treasure Coast in Martin County, Beth Abraham and the Treasure Coast Jewish Center stopped operations around 1990. A group of young families in and around Stuart organized a Reform congregation, Temple Beit HaYam in 1993, however, to fill the gap. The congregation reached a membership of 165 families in their first year. They hired a full-time spiritual leader, Rabbi Jonathan Kendall, in 1995 and built their own synagogue in 2000. As Temple Beit HaYam got started, St. Lucie County’s two Reform congregations negotiated a merger, with Temple Beth El and Temple Beth Israel joining together in 1994 to create Temple Beth El Israel, a 250-family congregation. The newly combined group sold both of their former synagogue buildings and constructed a new facility in the planned community of St. Lucie West, which opened in 1998. The Chabad-Lubavitch movement also began to develop a presence in Martin and St. Lucie Counties by the mid-1990s, and another short-lived Conservative congregation, Congregation B’nai Emet, operated in Vero Beach from that time until around 2005.

These changes in the Jewish congregational landscape of the Treasure Coast stemmed from the area’s continued development and population growth in the 1990s and 2000s. A 1999 demographic study indicated that the local Jewish community had one of the highest concentrations of older adults outside of Palm Beach County, and a 2004 update to that study showed that the Jewish population in Martin and southern Port-St. Lucie Counties had more than doubled in the past 18 years. Whereas the Treasure Coast Jewish community began as a somewhat isolated collection of small-town merchants and business people, it now bears some resemblance to larger, retirement-driven Jewish communities elsewhere on the Florida coast.

Despite moments of turbulence, Jewish life in Indian River, St. Lucie, and Martin Counties continued. At the southern end of the Treasure Coast in Martin County, Beth Abraham and the Treasure Coast Jewish Center stopped operations around 1990. A group of young families in and around Stuart organized a Reform congregation, Temple Beit HaYam in 1993, however, to fill the gap. The congregation reached a membership of 165 families in their first year. They hired a full-time spiritual leader, Rabbi Jonathan Kendall, in 1995 and built their own synagogue in 2000. As Temple Beit HaYam got started, St. Lucie County’s two Reform congregations negotiated a merger, with Temple Beth El and Temple Beth Israel joining together in 1994 to create Temple Beth El Israel, a 250-family congregation. The newly combined group sold both of their former synagogue buildings and constructed a new facility in the planned community of St. Lucie West, which opened in 1998. The Chabad-Lubavitch movement also began to develop a presence in Martin and St. Lucie Counties by the mid-1990s, and another short-lived Conservative congregation, Congregation B’nai Emet, operated in Vero Beach from that time until around 2005.

These changes in the Jewish congregational landscape of the Treasure Coast stemmed from the area’s continued development and population growth in the 1990s and 2000s. A 1999 demographic study indicated that the local Jewish community had one of the highest concentrations of older adults outside of Palm Beach County, and a 2004 update to that study showed that the Jewish population in Martin and southern Port-St. Lucie Counties had more than doubled in the past 18 years. Whereas the Treasure Coast Jewish community began as a somewhat isolated collection of small-town merchants and business people, it now bears some resemblance to larger, retirement-driven Jewish communities elsewhere on the Florida coast.

Selected Bibliography

Jewish Museum of Florida, Cocoa Beach and Fort Pierce files.

Estelle Linola Paden, “The Pioneers,” unpublished history, 1977. Available online.

Ira Sheskin, Jewish Community Studies – Martin-Port St. Lucie, 1983 and 1999.

Ellen Ann Stein, “So. Fla Temples Desecrated,” Jewish Floridian of South County, 1 June 1990.

Temple Beth El Israel, “Our History.”

Temple Beth Shalom, “History & Mission.”

Jewish Museum of Florida, Cocoa Beach and Fort Pierce files.

Estelle Linola Paden, “The Pioneers,” unpublished history, 1977. Available online.

Ira Sheskin, Jewish Community Studies – Martin-Port St. Lucie, 1983 and 1999.

Ellen Ann Stein, “So. Fla Temples Desecrated,” Jewish Floridian of South County, 1 June 1990.

Temple Beth El Israel, “Our History.”

Temple Beth Shalom, “History & Mission.”