Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Anniston, Alabama

Historical Overview

|

Situated in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains in northeast Alabama, Anniston has had a Jewish presence for over 120 years. Surrounded by iron ore deposits, Anniston was a private company town for its first two decades of existence. It was first developed during the Civil War, but wasn't appreciably settled until the arrival of industrialist Samuel Noble in the early 1870s. Noble established a major iron and steel works company, and Anniston was a private company town for employees. Deemed the “model city” by Atlanta newspaperman Henry Grady for its meticulously planned quality of life, Anniston flourished. It was chartered as a city in 1879, and finally opened to public settlement in 1883, under pressure from a rival real estate company looking to build a competing community.

|

Stories of the Jewish Community in Anniston

Early Jewish Residents

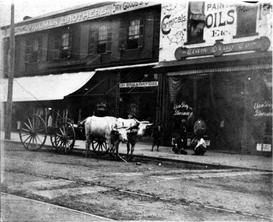

The first Jews arrived in Anniston after it opened to public settlement. Leon Ullman, likely the town's first Jewish resident, arrived in 1884. Ullman emigrated from German-speaking territories, worked as a traveling merchant, and had most recently spent time in Talladega, Alabama, 35 miles to the east. There, he had operated the Ullman Brothers Store with his brothers August, Solomon, Abe, and Leopold. All four brothers would eventually join Leon in his new Ullman brothers store in Anniston, selling dry goods on Noble Street.

A Growing Community

The Jewish population grew rapidly in its first decade as Jews from Germany and Russia joined the community. The 1887 Anniston city directory contained the names of Jewish merchants like Adolph Adler, Abe Fry, Simon Katzenstein, and Joseph Saks, and by the last decade of thenineteenth century, almost every store on Noble Street was owned by Jews.

The first Jews arrived in Anniston after it opened to public settlement. Leon Ullman, likely the town's first Jewish resident, arrived in 1884. Ullman emigrated from German-speaking territories, worked as a traveling merchant, and had most recently spent time in Talladega, Alabama, 35 miles to the east. There, he had operated the Ullman Brothers Store with his brothers August, Solomon, Abe, and Leopold. All four brothers would eventually join Leon in his new Ullman brothers store in Anniston, selling dry goods on Noble Street.

A Growing Community

The Jewish population grew rapidly in its first decade as Jews from Germany and Russia joined the community. The 1887 Anniston city directory contained the names of Jewish merchants like Adolph Adler, Abe Fry, Simon Katzenstein, and Joseph Saks, and by the last decade of thenineteenth century, almost every store on Noble Street was owned by Jews.

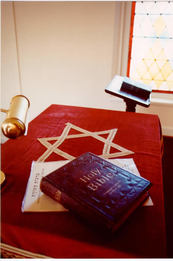

Organized Jewish Life in Anniston

In 1888, the 24 Jews of Anniston formed a Reform Jewish congregation, with the intent to establish the “worship of God in accordance with the usages and customs of our ancient religion” and “the preservation and perpetuation of the tenets and principles of Judaism.” The role of Anniston’s Jewish women in developing a religious and social community was considerable. Fifteen women of the Beth El congregation formed the Ladies Hebrew Benevolent Society in 1890, and promptly began to raise funds for a temple. For three years, the women actively solicited donations through a wide array of events and activities. Instead of limiting themselves to the traditional ancillary position in development efforts, the Anniston women expanded their influence into other areas of the project, including naming the building Temple Beth El, appointing the building committee, and raising the necessary money to construct the synagogue. Thanks to their efforts, the building was dedicated debt-free in December of 1893 by the esteemed New Orleans Rabbi Max Heller. The temple is still in use today.

The Sterne Family

Few congregants played as major a role in fostering the early growth of the Anniston Jewish community as Anselm and Henrietta Smith Sterne. Anselm, a veteran of the Confederate army, brought his wife and seven children to Anniston from Albany, Georgia around 1888. Henrietta, who hosted the founding meeting of the Ladies Hebrew Benevolent Society in 1890, was elected its first president; she had already organized the first religious school a year earlier. She held the office until her death in 1915, at which point the organization renamed itself the Henrietta Sterne Sisterhood in her honor. Anselm helped facilitate the construction of the Beth El Temple and arranged for the first student rabbi from Hebrew Union College to lead services in Anniston in 1900; previously, lay leaders such as Sterne had led prayers.

In 1888, the 24 Jews of Anniston formed a Reform Jewish congregation, with the intent to establish the “worship of God in accordance with the usages and customs of our ancient religion” and “the preservation and perpetuation of the tenets and principles of Judaism.” The role of Anniston’s Jewish women in developing a religious and social community was considerable. Fifteen women of the Beth El congregation formed the Ladies Hebrew Benevolent Society in 1890, and promptly began to raise funds for a temple. For three years, the women actively solicited donations through a wide array of events and activities. Instead of limiting themselves to the traditional ancillary position in development efforts, the Anniston women expanded their influence into other areas of the project, including naming the building Temple Beth El, appointing the building committee, and raising the necessary money to construct the synagogue. Thanks to their efforts, the building was dedicated debt-free in December of 1893 by the esteemed New Orleans Rabbi Max Heller. The temple is still in use today.

The Sterne Family

Few congregants played as major a role in fostering the early growth of the Anniston Jewish community as Anselm and Henrietta Smith Sterne. Anselm, a veteran of the Confederate army, brought his wife and seven children to Anniston from Albany, Georgia around 1888. Henrietta, who hosted the founding meeting of the Ladies Hebrew Benevolent Society in 1890, was elected its first president; she had already organized the first religious school a year earlier. She held the office until her death in 1915, at which point the organization renamed itself the Henrietta Sterne Sisterhood in her honor. Anselm helped facilitate the construction of the Beth El Temple and arranged for the first student rabbi from Hebrew Union College to lead services in Anniston in 1900; previously, lay leaders such as Sterne had led prayers.

The Murder of Harry Shiretzki

There were no acts of anti-Semitism recorded in the the early years of the Jewish community in Anniston, but in 1924 a terrible tragedy jarred the community. On May 23, Harry Shiretzki, the Jewish police chief of Anniston, was murdered by the owner of an illegal moonshining operation during a raid on the business. Shiretzki had gained local renown for his previous efforts to rid the town of liquor rackets—editorials in the Anniston newspaper called him the “terror of the tigers,” a nickname for moonshiners. His death prompted town-wide mourning. The funeral cortege spanned blocks in its parade through central Anniston and the temple sanctuary overflowed as Annistonians mourned their champion of law and order.

Holocaust Survivors in Anniston

The Anniston Jewish community received a relatively large number of Holocaust survivors in the twentieth century. Newlyweds Greta and Rudy Kemp fled Nazi Germany in 1937, crossing the border into Holland. They quickly immigrated to America in December 1937 and chose Anniston because of Greta’s many relatives who already lived there. Survivor Alfred Caro arrived in Anniston in 1955, setting up a staple of Anniston’s culinary scene, The Annistonian. For twenty years until Caro sold the business, the restaurant served as the center of both Anniston’s power brokers and fans of gourmet food. In 1974, grateful non-Jewish citizens placed a lighted menorah on the dome of Beth El in Caro’s honor.

There were no acts of anti-Semitism recorded in the the early years of the Jewish community in Anniston, but in 1924 a terrible tragedy jarred the community. On May 23, Harry Shiretzki, the Jewish police chief of Anniston, was murdered by the owner of an illegal moonshining operation during a raid on the business. Shiretzki had gained local renown for his previous efforts to rid the town of liquor rackets—editorials in the Anniston newspaper called him the “terror of the tigers,” a nickname for moonshiners. His death prompted town-wide mourning. The funeral cortege spanned blocks in its parade through central Anniston and the temple sanctuary overflowed as Annistonians mourned their champion of law and order.

Holocaust Survivors in Anniston

The Anniston Jewish community received a relatively large number of Holocaust survivors in the twentieth century. Newlyweds Greta and Rudy Kemp fled Nazi Germany in 1937, crossing the border into Holland. They quickly immigrated to America in December 1937 and chose Anniston because of Greta’s many relatives who already lived there. Survivor Alfred Caro arrived in Anniston in 1955, setting up a staple of Anniston’s culinary scene, The Annistonian. For twenty years until Caro sold the business, the restaurant served as the center of both Anniston’s power brokers and fans of gourmet food. In 1974, grateful non-Jewish citizens placed a lighted menorah on the dome of Beth El in Caro’s honor.

Jewish Businesses in Anniston

In Anniston’s early years, most of the local Jews were merchants, a vocation most had practiced earlier in Germany. Families like the Sternes, Saks, and Ullmans owned and operated major department stores along Noble Street. Smaller Jewish-owned stores like Adolph Adler’s Beehive Store and Julius Levy’s tailoring store coexisted with these larger establishments. Later in the twentieth century, Jewish entrepreneurs like Alfred Caro, with his upscale restaurant, pursued different businesses. Gershon Weinberg, an active member of Beth El, owned the Old Smokehouse Bar-B-Q on South Quintard Street.

The Civil Rights Movement

The Civil Rights movement of the late 1950s and early 1960s rattled the relatively tranquil existence of Anniston Jews. As some Southern Jews, especially rabbis, began to join African Americans in their fight for equality, white supremacist groups like the Ku Klux Klan sought retaliation. Anniston Jews watched as their surrounding communities weathered assaults. A failed bomb attempt on Birmingham’s Temple Beth El occurred in April of 1958, and on October 12th of that year, extremists bombed The Temple in Atlanta with dynamite. Gadsden, Alabama, closer than either city to Anniston, was targeted in March of 1965 when a homemade bomb was thrown into the sanctuary.

On Mother’s Day, May 1961, Anniston Jews witnessed an incident in their own town. One of the desegregated buses housing the “Freedom Riders” was assaulted on the perimeter of Anniston, with agitators throwing rocks and eventually setting fire to the bus. As the Civil Rights protestors escaped from the burning vehicle, the mob beat them. Anniston’s student rabbi, Sanford Ragis, witnessed the incident, later recalling the “terrible times as we tried to establish justice in our country—and that Anniston was for a short time in an uncomfortable spotlight.” Like many Southern Jews, they were diffident in responding against white aggression, but a newspaper advertisement from the time condemning the violence included the names of thirteen local Jews.

In Anniston’s early years, most of the local Jews were merchants, a vocation most had practiced earlier in Germany. Families like the Sternes, Saks, and Ullmans owned and operated major department stores along Noble Street. Smaller Jewish-owned stores like Adolph Adler’s Beehive Store and Julius Levy’s tailoring store coexisted with these larger establishments. Later in the twentieth century, Jewish entrepreneurs like Alfred Caro, with his upscale restaurant, pursued different businesses. Gershon Weinberg, an active member of Beth El, owned the Old Smokehouse Bar-B-Q on South Quintard Street.

The Civil Rights Movement

The Civil Rights movement of the late 1950s and early 1960s rattled the relatively tranquil existence of Anniston Jews. As some Southern Jews, especially rabbis, began to join African Americans in their fight for equality, white supremacist groups like the Ku Klux Klan sought retaliation. Anniston Jews watched as their surrounding communities weathered assaults. A failed bomb attempt on Birmingham’s Temple Beth El occurred in April of 1958, and on October 12th of that year, extremists bombed The Temple in Atlanta with dynamite. Gadsden, Alabama, closer than either city to Anniston, was targeted in March of 1965 when a homemade bomb was thrown into the sanctuary.

On Mother’s Day, May 1961, Anniston Jews witnessed an incident in their own town. One of the desegregated buses housing the “Freedom Riders” was assaulted on the perimeter of Anniston, with agitators throwing rocks and eventually setting fire to the bus. As the Civil Rights protestors escaped from the burning vehicle, the mob beat them. Anniston’s student rabbi, Sanford Ragis, witnessed the incident, later recalling the “terrible times as we tried to establish justice in our country—and that Anniston was for a short time in an uncomfortable spotlight.” Like many Southern Jews, they were diffident in responding against white aggression, but a newspaper advertisement from the time condemning the violence included the names of thirteen local Jews.

The Jewish Community in Anniston Today

In recent years, Anniston Jews have faced the same issues confronting other small Jewish communities in the South. The Beth El congregation membership has aged or left the town for economic reasons, and outside Jewish families are not replacing them. Despite this decline, Beth El celebrated its 120th birthday in 2004, and remains financially stable.

Anniston has worked to revitalize itself as an attractive residential town. In 2003, the U.S. Army began destroying the nerve agents it had stored in the army depot there, a feature that had produced the city’s nickname of “Toxic Town.” The defunct army base of Fort McClellan is being redeveloped for civilian use. Against this background, the continuation of the Anniston Jewish community will likely hinge on the vagaries of demographic and economic change that have always guided the path of the “Model City.” In the spirit of the founding families—the Ullman, Saks, and Sterne clans—contemporary Anniston Jews continue to sustain their small community. In 1999, an exhibit on Anniston’s Jewish community, produced by local historian Sherry Blanton, opened at the Calhoun County Public Library and is currently on display in the social hall at Temple Beth El.

Anniston has worked to revitalize itself as an attractive residential town. In 2003, the U.S. Army began destroying the nerve agents it had stored in the army depot there, a feature that had produced the city’s nickname of “Toxic Town.” The defunct army base of Fort McClellan is being redeveloped for civilian use. Against this background, the continuation of the Anniston Jewish community will likely hinge on the vagaries of demographic and economic change that have always guided the path of the “Model City.” In the spirit of the founding families—the Ullman, Saks, and Sterne clans—contemporary Anniston Jews continue to sustain their small community. In 1999, an exhibit on Anniston’s Jewish community, produced by local historian Sherry Blanton, opened at the Calhoun County Public Library and is currently on display in the social hall at Temple Beth El.

Sources

Blanton, Sherry. “Lives of Quiet Affirmation: the Jews of Calhoun County,” and “A History of Temple Beth El.