Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Arkansas

Overview >> Arkansas

The first Jew to settle in Arkansas was Abraham Block, who opened a store in Washington in 1823, soon becoming one of the wealthiest men in Hempstead County. Block settled in Washington when there were no Jewish congregations or institutions in the Arkansas Terrritory. He was a charter member of the first Jewish synagogue in the region, Congregation Gates of Mercy in New Orleans, joining in 1828. Yet the lack of any organized Jewish life in Arkansas at the time took its toll on his family, and few of his children remained within the faith. Block’s life in Arkansas highlights the challenges that Jews have often faced in a state largely isolated from the centers of American Jewish life.

These difficulties became a little easier as growing numbers of Jews from central Europe began to arrive in Arkansas in the years before the civil war. These immigrants were part of the “German wave” of Jewish immigration, which settled primarily in the large cities of the Northeast and Midwest. But a significant minority of Jews from the German states and from Alsace-Lorraine settled in the rural South, including Arkansas. At the time of the Civil War, they had established small but growing Jewish communities in Little Rock, Fort Smith, Pine Bluff, Devalls Bluff, Van Buren, Jonesboro, and Batesville. Despite their relatively short time in the state, Jews felt closely tied to their new home. Of the approximately 300 Jews in Arkansas at the time of the war, fifty-three fought for the Confederacy.

These difficulties became a little easier as growing numbers of Jews from central Europe began to arrive in Arkansas in the years before the civil war. These immigrants were part of the “German wave” of Jewish immigration, which settled primarily in the large cities of the Northeast and Midwest. But a significant minority of Jews from the German states and from Alsace-Lorraine settled in the rural South, including Arkansas. At the time of the Civil War, they had established small but growing Jewish communities in Little Rock, Fort Smith, Pine Bluff, Devalls Bluff, Van Buren, Jonesboro, and Batesville. Despite their relatively short time in the state, Jews felt closely tied to their new home. Of the approximately 300 Jews in Arkansas at the time of the war, fifty-three fought for the Confederacy.

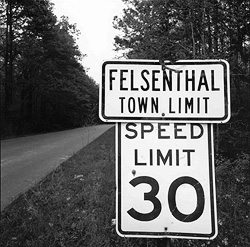

After the war, as Arkansas became increasingly tied into national trading markets, Jewish peddlers and merchants were drawn to the state. With close economic connections to Jewish wholesalers in Memphis, St. Louis, Cincinnati, and Louisville, these peddlers and merchants fanned out across Arkansas, helping to develop isolated parts of the state. Fourteen towns in Arkansas were founded by Jews, or named after early Jewish residents, including Atheimer, Berger, Bertig, Felsenthal, Goldman, and Levy.

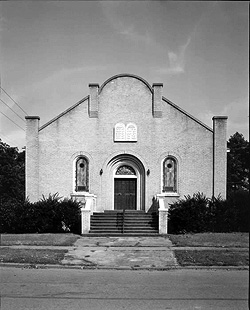

Arkansas Jews began to form religious institutions soon after they began to arrive in the state in significant numbers. In 1839, the small but growing number of Jews in Little Rock first began to worship together. It was not until 1866 that the state’s first Jewish congregation, B’nai Israel in Little Rock, was formally chartered. Soon after, a spate of congregations were formed in the state, reflecting how widely Jews had settled in Arkansas. In 1867, Congregation Anshe Emeth of Pine Bluff and Temple Beth El of Helena were founded. Congregations were also founded in Camden (1869), Hot Springs (1878), Texarkana (1884), Jonesboro (1897), Newport (1905), Dermott (1905), Eudora (1912), Osceola (1913), Forrest City (1914), Wynne (1915), Marianna (1920), Blytheville (1924), El Dorado (1926), McGehee (1947), Fayetteville (1981), and Bentonville (2004).

Arkansas Jews began to form religious institutions soon after they began to arrive in the state in significant numbers. In 1839, the small but growing number of Jews in Little Rock first began to worship together. It was not until 1866 that the state’s first Jewish congregation, B’nai Israel in Little Rock, was formally chartered. Soon after, a spate of congregations were formed in the state, reflecting how widely Jews had settled in Arkansas. In 1867, Congregation Anshe Emeth of Pine Bluff and Temple Beth El of Helena were founded. Congregations were also founded in Camden (1869), Hot Springs (1878), Texarkana (1884), Jonesboro (1897), Newport (1905), Dermott (1905), Eudora (1912), Osceola (1913), Forrest City (1914), Wynne (1915), Marianna (1920), Blytheville (1924), El Dorado (1926), McGehee (1947), Fayetteville (1981), and Bentonville (2004).

In the late 19th and early 20th century, a new wave of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe began to arrive in the United States. Pushed to leave Europe by anti-Semitic violence and legal restrictions, these new arrivals crowded into the urban ghettos of the Northeast and Midwest. A tiny minority came to the South, often drawn by family ties and greater economic opportunity. The Jewish population of Arkansas swelled from this influx of new immigrants. In 1878, 1,466 Jews lived in Arkansas, most from Germany or Alsace. By 1927, just after the Eastern European immigration wave was ended by national immigration restriction, 8,850 Jews lived in Arkansas. These newcomers followed the path cut by earlier Jewish immigrants, beginning as roving peddlers and working their way up to retail store ownership. In many small towns, these Eastern European Jews fit into the congregations and societies that had been founded by the earlier German Jews. Where their numbers were great enough, Eastern European Jews formed their own congregations that were more Orthodox in practice. Most of the state’s early congregations had become Reform by the end of the 19th century, incorporating English prayers, mixed-gender seating, and other elements of Protestant Christian worship. In Little Rock, El Dorado, Fort Smith, Hot Springs, Jonesboro, and Pine Bluff, Eastern European Jews founded their own Orthodox congregations.

When the first rabbi settled in Arkansas in the 1870s, state law required that a minister be Christian in order to officiate at a wedding. After a lobbying effort by Arkansas Jews, the state legislature amended the law to include rabbis. As this example shows, Arkansas Jews have been very involved in civic affairs in their state. They have served as mayors of Little Rock, Dumas, Helena, El Dorado, Holly Grove, West Memphis, and Pine Bluff. Jonas Levy was elected to the Little Rock city council in 1857, and served as mayor throughout the Civil War. Several Jews were elected to local office and the state legislature. Charles Jacobson, a close ally of populist Governor and Senator Jeff Davis, served two terms in the state senate. Samuel Levine represented Pine Bluff in the Arkansas House of Representatives and Senate for twenty years; he even once ran for lieutenant governor. This high degree of political involvement was not unique to Arkansas, as Jews across the South won election to political office in areas where they were a tiny minority. Their prominent role in the southern merchant class usually served as their entree to local politics.

When the first rabbi settled in Arkansas in the 1870s, state law required that a minister be Christian in order to officiate at a wedding. After a lobbying effort by Arkansas Jews, the state legislature amended the law to include rabbis. As this example shows, Arkansas Jews have been very involved in civic affairs in their state. They have served as mayors of Little Rock, Dumas, Helena, El Dorado, Holly Grove, West Memphis, and Pine Bluff. Jonas Levy was elected to the Little Rock city council in 1857, and served as mayor throughout the Civil War. Several Jews were elected to local office and the state legislature. Charles Jacobson, a close ally of populist Governor and Senator Jeff Davis, served two terms in the state senate. Samuel Levine represented Pine Bluff in the Arkansas House of Representatives and Senate for twenty years; he even once ran for lieutenant governor. This high degree of political involvement was not unique to Arkansas, as Jews across the South won election to political office in areas where they were a tiny minority. Their prominent role in the southern merchant class usually served as their entree to local politics.

Despite the fact that they were always less than one-half of one percent of Arkansas’ population, Jews have played an important role in the social and economic development of the state. The Kempner, Blass, and Pfeiffer families all owned leading department stores. Howard Eichenbaum was a celebrated architect who designed many significant buildings in Little Rock. Jacob Treiber of Helena was the first Jew in America ever appointed as a federal judge, serving the Eastern Arkansas district from 1900 to 1927. Julian Waterman was the first dean of the University of Arkansas Law School. Rabbi Ira Sanders, who served Little Rock’s Congregation B’nai Israel from 1926 to 1963, became an outspoken supporter of racial equality during the turbulent era of civil rights. Cyrus Adler, who was born in Van Buren, became one of the most prominent Jewish leaders in America during the early 20th century, serving as president of the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York, the American Jewish Committee, and the American Jewish Historical Society.

In 1937, the year of the most comprehensive study of America’s Jewish population ever conducted, 6,510 Jews lived in 72 different cities or towns in Arkansas. Little Rock had the largest community, with 2,500 Jews, while 37 towns had ten or fewer Jews. During the second half of the 20th century, the Jewish population of Arkansas steadily decreased. In 2001, there were only an estimated 1,675 Jews in the state. Congregations in Helena, Blytheville, and El Dorado closed, while others struggled to survive. The Jewish population has become concentrated in a few communities like Little Rock, Hot Springs, Fayetteville, and Bentonville. In 1937, thirteen cities in Arkansas had more than fifty Jews. In 2006, only four did. As of 2006, only congregations in Little Rock and Hot Springs had full-time rabbis.

In 1937, the year of the most comprehensive study of America’s Jewish population ever conducted, 6,510 Jews lived in 72 different cities or towns in Arkansas. Little Rock had the largest community, with 2,500 Jews, while 37 towns had ten or fewer Jews. During the second half of the 20th century, the Jewish population of Arkansas steadily decreased. In 2001, there were only an estimated 1,675 Jews in the state. Congregations in Helena, Blytheville, and El Dorado closed, while others struggled to survive. The Jewish population has become concentrated in a few communities like Little Rock, Hot Springs, Fayetteville, and Bentonville. In 1937, thirteen cities in Arkansas had more than fifty Jews. In 2006, only four did. As of 2006, only congregations in Little Rock and Hot Springs had full-time rabbis.

The only exception to this downward trend is Bentonville. In the 21st century, as WalMart has encouraged major suppliers to open offices in its corporate hometown, Bentonville has seen its Jewish population skyrocket. In 2004, a group of thirty families founded Bentonville’s first Jewish congregation, Etz Chaim, which has quickly become the fastest growing congregation in the state. Bentonville is the exception to the regional trend of small town Jewish communities declining. Most of the founding members of Etz Chaim are not Arkansas natives. Unlike the peddlers and merchants who initially settled in Arkansas in the 19th century, these 21st century migrants are executives at large corporations. They represent the generation of Jewish professionals who have largely replaced the Jewish merchant class in the south’s metropolitan areas.

With this tremendous growth in Bentonville, the Jewish population of Arkansas will likely remain steady, though small Jewish congregations and communities will continue to decline. Many Jewish children raised in Arkansas, as in small towns throughout the South, do not return home after college, as they seek greater economic opportunity elsewhere, the same impulse that brought Jews to Arkansas during the 19th and early 20th centuries.

The definitive work on the Jews of Arkansas is Carolyn Gray LeMaster's A Corner of the Tapestry: A History of the Jewish Experience in Arkansas, 1820s-1990s (University of Arkansas Press, 1994). Our Arkansas Digital Archive owes a great deal to her research.

With this tremendous growth in Bentonville, the Jewish population of Arkansas will likely remain steady, though small Jewish congregations and communities will continue to decline. Many Jewish children raised in Arkansas, as in small towns throughout the South, do not return home after college, as they seek greater economic opportunity elsewhere, the same impulse that brought Jews to Arkansas during the 19th and early 20th centuries.

The definitive work on the Jews of Arkansas is Carolyn Gray LeMaster's A Corner of the Tapestry: A History of the Jewish Experience in Arkansas, 1820s-1990s (University of Arkansas Press, 1994). Our Arkansas Digital Archive owes a great deal to her research.