Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Dumas/McGehee, Arkansas

Overview

Desha County in southeast Arkansas is part of the historical home of the Quapaw Nation, who planted crops in the fertile alluvial soil and hunted game in the hardwood forests that grew there. The area was also a site of frequent floods from the Arkansas, White, and Mississippi Rivers, which converge in the northeast portion of Desha County. Euro-American settlement proceeded somewhat slowly in Desha County, but steamboat travel allowed for the establishment of large cotton farms by the mid-19th century. The 1860 census recorded some 5,400 residents in the county, nearly sixty percent of whom were enslaved Black workers. As the area continued to develop in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, towns including Dumas, Arkansas City, and McGehee emerged as local market hubs that served the surrounding countryside.

Jewish settlement in Desha County began in the late 19th century and accelerated in the early 20th century, but the small Jewish population never concentrated in a single town. The dispersed Jewish community of far southeast Arkansas included residents of neighboring Drew and Chicot Counties as well. Additionally, family and business connections linked many Jews of far southeast Arkansas to nearby Pine Bluff, the largest city in the area. Several Jewish families played significant roles in local business and civic life during the 20th century, even before Temple Meir Chayim of McGehee emerged as a local hub for Jewish congregational life in the 1940s. The area’s Jewish population began to decline by the 1970s, however, and the small Jewish community of southeast Arkansas closed Meir Chayim in 2016.

Jewish settlement in Desha County began in the late 19th century and accelerated in the early 20th century, but the small Jewish population never concentrated in a single town. The dispersed Jewish community of far southeast Arkansas included residents of neighboring Drew and Chicot Counties as well. Additionally, family and business connections linked many Jews of far southeast Arkansas to nearby Pine Bluff, the largest city in the area. Several Jewish families played significant roles in local business and civic life during the 20th century, even before Temple Meir Chayim of McGehee emerged as a local hub for Jewish congregational life in the 1940s. The area’s Jewish population began to decline by the 1970s, however, and the small Jewish community of southeast Arkansas closed Meir Chayim in 2016.

Early Jewish Settlers

The intersection of Waterman and Main Streets in downtown Dumas, 2023.

The intersection of Waterman and Main Streets in downtown Dumas, 2023.

The first known Jew to put down roots in Dumas was Gus Waterman, who arrived in the United States from Prussia in 1866 at the age of seventeen. Waterman first settled in Maine but eventually made his way to Memphis, where he worked as a peddler. In 1879 he opened a store in Dumas, betting that the arrival of rail transport would lead to a boom in the local economy. Waterman’s mercantile business succeeded, and he also took on a variety of other civic and commercial endeavors. He served as postmaster from 1881 to 1887 and won election as the first mayor of Dumas following its incorporation in 1904. He was also credited for promoting a levee system to protect Dumas from flooding. Waterman additionally owned a livery stable business and acquired a large amount of farmland, which was presumably maintained by Black sharecroppers and tenant farmers. In 1882 he wed Rachel Ulman of Memphis; while she lived with their children in Pine Bluff, he maintained a rented room in Dumas during the early 20th century.

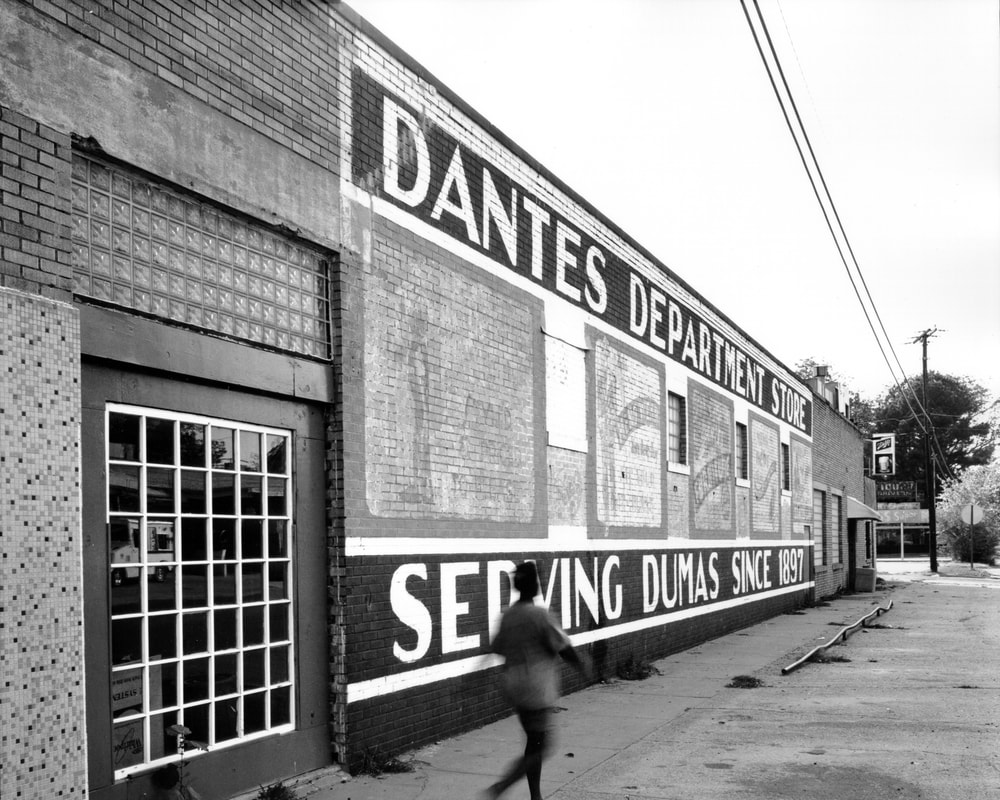

As southeast Arkansas continued to develop in the late 19th century, it attracted new Jewish settlers. Charles Dante arrived in Pine Bluff in 1892 after immigrating from Eastern Europe in 1890 and spending time in New York City. A cousin in Pine Bluff encouraged him to move there and helped him secure a position with William Rozenzweig’s mercantile company. Dante peddled merchandise and worked as a store clerk. On the side, he also carved matches from salvaged wood. Having identified Dumas as a promising location for a retail business, Dante saved $500 and opened a store there in 1897. He was twenty years old. Three years later he married Antoinette “Toney” Stiel of Little Rock and opened a larger store. When a 1925 fire destroyed that business, he once again opened a larger one, this time named Dante’s Department Store. Like other successful retailers, Dante branched out into the cotton business, establishing a ginning company that stayed in the family for generations. He also owned thousands of acres of farmland.

As southeast Arkansas continued to develop in the late 19th century, it attracted new Jewish settlers. Charles Dante arrived in Pine Bluff in 1892 after immigrating from Eastern Europe in 1890 and spending time in New York City. A cousin in Pine Bluff encouraged him to move there and helped him secure a position with William Rozenzweig’s mercantile company. Dante peddled merchandise and worked as a store clerk. On the side, he also carved matches from salvaged wood. Having identified Dumas as a promising location for a retail business, Dante saved $500 and opened a store there in 1897. He was twenty years old. Three years later he married Antoinette “Toney” Stiel of Little Rock and opened a larger store. When a 1925 fire destroyed that business, he once again opened a larger one, this time named Dante’s Department Store. Like other successful retailers, Dante branched out into the cotton business, establishing a ginning company that stayed in the family for generations. He also owned thousands of acres of farmland.

McGehee, twenty miles south of Dumas, developed a Jewish population somewhat later. Jewish migrants to southern Desha County initially gravitated toward Arkansas City, a port town on the Mississippi River. Abraham Dreidel, for instance, owned a string of confectionary stores in the area with non-Jewish business partners. He served several terms as the mayor of Arkansas City in the early years of the twentieth century and became Arkansas’s first Jewish state senator in 1907.

The Wolff family constituted another significant piece of the local Jewish community and linked Dumas to McGehee, twenty miles to the south. Leo Wolff first arrived in the area in the 1910s and opened a branch of the Wolff Brothers Department Store in McGehee. A brother and sister-in-law, Sam and Sadie Wolff, opened a Dumas location in 1925. Their son Haskell joined the Dumas business after World War II and became a visible business and civic leader in his own right.

McGehee attracted additional Jewish residents after the Great Flood of 1927 not only caused catastrophic damage to Arkansas City but also put an end to the town’s growth. As the waters subsided, the river settled into a new channel approximately a mile east of the town, rendering the river port and the nearby railroads obsolete. McGehee, located on higher ground and with its own rail access, drew a number of former Arkansas City residents, including several Jewish business owners.

By 1930 it was home to approximately 3,500 people, including about fifty Jews. Among prominent local Jews were Bill and Adolph Hamburger, who sold livestock and horses before getting into the cotton business. Martin Dreyfus ran a large grain store in McGehee and served as president of the local Lions Club. Charles Fleisig had owned stores in De Witt and Little Rock before moving to McGehee and opening the New York Bargain Store in 1932. Like Charles Dante, David Meyer had worked for William Rosenzweig of Pine Bluff, first managing Rosenzweig’s McGehee store and then opening his own successful business.

The Wolff family constituted another significant piece of the local Jewish community and linked Dumas to McGehee, twenty miles to the south. Leo Wolff first arrived in the area in the 1910s and opened a branch of the Wolff Brothers Department Store in McGehee. A brother and sister-in-law, Sam and Sadie Wolff, opened a Dumas location in 1925. Their son Haskell joined the Dumas business after World War II and became a visible business and civic leader in his own right.

McGehee attracted additional Jewish residents after the Great Flood of 1927 not only caused catastrophic damage to Arkansas City but also put an end to the town’s growth. As the waters subsided, the river settled into a new channel approximately a mile east of the town, rendering the river port and the nearby railroads obsolete. McGehee, located on higher ground and with its own rail access, drew a number of former Arkansas City residents, including several Jewish business owners.

By 1930 it was home to approximately 3,500 people, including about fifty Jews. Among prominent local Jews were Bill and Adolph Hamburger, who sold livestock and horses before getting into the cotton business. Martin Dreyfus ran a large grain store in McGehee and served as president of the local Lions Club. Charles Fleisig had owned stores in De Witt and Little Rock before moving to McGehee and opening the New York Bargain Store in 1932. Like Charles Dante, David Meyer had worked for William Rosenzweig of Pine Bluff, first managing Rosenzweig’s McGehee store and then opening his own successful business.

Jewish Life in Dumas and McGehee

The number of Jewish residents in southeast Arkansas increased during the early 20th century, but the population was both small and widely dispersed among the small towns of the area. From 1905 until the 1920s local Jews met for holidays in Dermott (south of McGehee in Chicot County) or traveled north to Pine Bluff. A 1913 newspaper, for instance, indicates that Charles and Toney Dante traveled from Dumas to Pine Bluff for Yom Kippur services, as did the family of Morris Rosenzweig of Lake Village.

Although the Jewish residents of southeast Arkansas were physically distant from major centers of Jewish life, they remained connected to national and transnational Jewish networks. Sadie Wolff, for instance, was born in New York City, and her parents still lived there. Sadie and Sam Wolff’s daughter Grace spent several summers with her grandparents in New York during her childhood, but ultimately married a Jewish man from Dermott and spent most of her life in Dumas.

As conditions for Jews living in Germany deteriorated during the 1930s, Jews in southeast Arkansas paid close attention. Adolph and Bill Hamburger assisted several relatives in escaping Europe, including their brother and his family. In 1936 Adolph Hamburger helped secure a visa for their niece Elsie Hamburger (later Phillips) to leave Bad Kissingen. Two years later her parents, Henry and Rose, and a sister, Ruth, emigrated to the United States, living first in New York and then in McGehee. Elsie eventually married another local emigree, Harry Phillips. Phillips was a nephew of Charles Dante and just one of the refugees whom Dante supported. Phillips came from Poland in 1938 and worked in Dante’s store before serving in the United States military during World War II. After the war he returned to Dumas, married Elsie Hamburger, and worked for the Dante-Tanenbaum business for many years.

Although the Jewish residents of southeast Arkansas were physically distant from major centers of Jewish life, they remained connected to national and transnational Jewish networks. Sadie Wolff, for instance, was born in New York City, and her parents still lived there. Sadie and Sam Wolff’s daughter Grace spent several summers with her grandparents in New York during her childhood, but ultimately married a Jewish man from Dermott and spent most of her life in Dumas.

As conditions for Jews living in Germany deteriorated during the 1930s, Jews in southeast Arkansas paid close attention. Adolph and Bill Hamburger assisted several relatives in escaping Europe, including their brother and his family. In 1936 Adolph Hamburger helped secure a visa for their niece Elsie Hamburger (later Phillips) to leave Bad Kissingen. Two years later her parents, Henry and Rose, and a sister, Ruth, emigrated to the United States, living first in New York and then in McGehee. Elsie eventually married another local emigree, Harry Phillips. Phillips was a nephew of Charles Dante and just one of the refugees whom Dante supported. Phillips came from Poland in 1938 and worked in Dante’s store before serving in the United States military during World War II. After the war he returned to Dumas, married Elsie Hamburger, and worked for the Dante-Tanenbaum business for many years.

|

Multimedia: Ruth Frenkel was born in Bad Kissingen, Germany, and came with her family to the United States when she was a young child. In this excerpt from a 2013 oral history interview, Ruth talks about her family's escape from Nazi Germany and their new lives in southeast Arkansas.

|

|

Civic and Social Life

Throughout the twentieth century Jewish residents of southeast Arkansas involved themselves in local civic life, as Gus Waterman had in early-20th-century Dumas. In the wake of the devastating 1927 flood, Jewish merchants such as Charles Dante, Sam Abowitz, and Sam Wolchansky earned recognition for helping local farmers obtain supplies to revive the local agricultural economy. Charles Dante stood out especially as a local leader. He served as president of the local school board and chamber of commerce, and he won the Dumas mayoral election in 1919, making him Dumas’s second Jewish mayor in its first fifteen years of existence. Over the decades, the Dante family donated land for a city park, a public pool, and a new public school, along with several churches. Charles’ wife, Antoinette “Toney” Dante, was also a local leader in the early 20th century. She helped found the first public library in Dumas and participated in the United Methodist Women’s Circle since there were no Jewish women’s groups in the area at the time. Her participation in the church group reflected local Jews’ acceptance among their white, Christian neighbors.

Jews in Dumas, McGehee, and nearby towns occupied a relatively privileged position in a society defined by racial segregation, economic inequality, and political disenfranchisement. As in other parts of Arkansas Delta, Black residents made up a majority of the population in Desha County, but social customs, legal restrictions, and anti-Black violence limited their economic and political power. In some instances, Jewish families acted to ameliorate the most glaring inequalities, but they also played leading roles in a fundamentally white supremacist power structure.

An incident from 1920 illustrates the complexity of Jewish participation in Desha County’s racial hierarchy. According to newspaper reports, on January 21, 1920, Deputy Sheriff J. H. Breedlove and two other white men attempted to arrest a Black man, “Doc” Hayes, in a Black settlement about eight miles east of Dumas. A group of armed Black residents confronted Breedlove and demanded that he release Hayes. They opened fire when Breedlove refused, and Hayes escaped. This affront to white authority aroused fear among some local white residents; newspapers reported that more than 95 percent of the population east of Dumas was Black, and unfounded rumors of a Black uprising in Phillips County (some sixty miles north) had led to catastrophic anti-Black violence in Elaine, Arkansas, less than four months earlier.

Newspaper accounts indicate that Charles Dante, who had been elected mayor of Dumas in 1919, responded quickly to the potential crisis. A white posse failed to locate the escapee or his accomplices the night after the attack, and white locals held a mass meeting that evening at which they apparently came to the consensus that there was no risk of Black insurrection. Mayor Dante immediately requested the assistance of federal soldiers from Camp Pike, who arrived the next day. Mass violence did not erupt, however, and the troops quickly returned from Dumas.

Inflammatory accounts of the potential “race riot” circulated in white newspapers throughout Arkansas and surrounding states. The articles, loaded with racist insinuations, obscure Mayor Dante’s motivations for requesting the military intervention. They emphasize the threat of Black lawlessness, presenting the presence of heavily armed federal troops as a deterrent for Black insurrection. (Some accounts of the Elaine Massacre describe indiscriminate killing by United States soldiers.) At the same time, however, Dante may have been equally concerned about anti-Black mob violence. According to the Arkansas Democrat, Mayor Dante “felt that if civilian posses were sent out to search for the ring leaders in Wednesday’s affair their judgment might have been overbalanced by their personal feelings and bloodshed might have resulted.” Ultimately, Dante appears in this instance as both a pillar of the local white power structure and an opponent of extralegal mob violence.

Jews in Dumas, McGehee, and nearby towns occupied a relatively privileged position in a society defined by racial segregation, economic inequality, and political disenfranchisement. As in other parts of Arkansas Delta, Black residents made up a majority of the population in Desha County, but social customs, legal restrictions, and anti-Black violence limited their economic and political power. In some instances, Jewish families acted to ameliorate the most glaring inequalities, but they also played leading roles in a fundamentally white supremacist power structure.

An incident from 1920 illustrates the complexity of Jewish participation in Desha County’s racial hierarchy. According to newspaper reports, on January 21, 1920, Deputy Sheriff J. H. Breedlove and two other white men attempted to arrest a Black man, “Doc” Hayes, in a Black settlement about eight miles east of Dumas. A group of armed Black residents confronted Breedlove and demanded that he release Hayes. They opened fire when Breedlove refused, and Hayes escaped. This affront to white authority aroused fear among some local white residents; newspapers reported that more than 95 percent of the population east of Dumas was Black, and unfounded rumors of a Black uprising in Phillips County (some sixty miles north) had led to catastrophic anti-Black violence in Elaine, Arkansas, less than four months earlier.

Newspaper accounts indicate that Charles Dante, who had been elected mayor of Dumas in 1919, responded quickly to the potential crisis. A white posse failed to locate the escapee or his accomplices the night after the attack, and white locals held a mass meeting that evening at which they apparently came to the consensus that there was no risk of Black insurrection. Mayor Dante immediately requested the assistance of federal soldiers from Camp Pike, who arrived the next day. Mass violence did not erupt, however, and the troops quickly returned from Dumas.

Inflammatory accounts of the potential “race riot” circulated in white newspapers throughout Arkansas and surrounding states. The articles, loaded with racist insinuations, obscure Mayor Dante’s motivations for requesting the military intervention. They emphasize the threat of Black lawlessness, presenting the presence of heavily armed federal troops as a deterrent for Black insurrection. (Some accounts of the Elaine Massacre describe indiscriminate killing by United States soldiers.) At the same time, however, Dante may have been equally concerned about anti-Black mob violence. According to the Arkansas Democrat, Mayor Dante “felt that if civilian posses were sent out to search for the ring leaders in Wednesday’s affair their judgment might have been overbalanced by their personal feelings and bloodshed might have resulted.” Ultimately, Dante appears in this instance as both a pillar of the local white power structure and an opponent of extralegal mob violence.

In subsequent decades, the descendants of early Jewish arrivals to Dumas and surrounding towns continued to play significant roles in local and state affairs. Julian Waterman, the son of Gus and Rachel (Ulman) Waterman, became the founding dean of the University of Arkansas Law School in 1924. State leaders reportedly considered nominating Waterman to the state supreme court at one point, although he declined the offer. His brother Lawrence remained in Dumas and ran the Waterman family business until his death in 1948.

In 1929 Naomi Dante, daughter of Charles and Toney, married Bernard Tanenbaum of Monroe, Louisiana. After the couple settled in Dumas in 1932, the Tanenbaum and Dante names became closely linked. Bernard Tanenbaum joined the Dante business and later formed the DanTan clothing manufacturing company, which became a major industrial employer in Dumas. The family sold DanTan in 1957, at which point Tanenbaum created United Dollar Store, which originally occupied the site of the Dante Department Store in downtown Dumas but soon grew into a successful regional chain. The Tanenbaums continued the Dante family’s philanthropic legacy throughout the 20th century, donating land for a new high school and the Desha County Museum. When the city opened a new white-only library in the 1950s, the Tanenbaum family donated money to build a second library for the Black community and ensured that it contained the same collection of books. In 1994 the Tanenbaums dedicated a community theater in Dumas in the old Dante’s Department Store building, which operated for a number of years under the direction of the Dumas Area Arts Council.

In 1929 Naomi Dante, daughter of Charles and Toney, married Bernard Tanenbaum of Monroe, Louisiana. After the couple settled in Dumas in 1932, the Tanenbaum and Dante names became closely linked. Bernard Tanenbaum joined the Dante business and later formed the DanTan clothing manufacturing company, which became a major industrial employer in Dumas. The family sold DanTan in 1957, at which point Tanenbaum created United Dollar Store, which originally occupied the site of the Dante Department Store in downtown Dumas but soon grew into a successful regional chain. The Tanenbaums continued the Dante family’s philanthropic legacy throughout the 20th century, donating land for a new high school and the Desha County Museum. When the city opened a new white-only library in the 1950s, the Tanenbaum family donated money to build a second library for the Black community and ensured that it contained the same collection of books. In 1994 the Tanenbaums dedicated a community theater in Dumas in the old Dante’s Department Store building, which operated for a number of years under the direction of the Dumas Area Arts Council.

Meir Chayim

Although Jewish residents of Dumas and nearby towns played pivotal roles in the development of Desha County, it took several decades to establish local Jewish institutions. In 1927 a group of Jewish men founded a local B’nai B’rith chapter, but the scattered Jewish population of Desha County did not meet regularly for religious services until 1940, when Henry Hamburger of McGehee hosted high holiday services in his home. Soon the community secured other venues in McGehee, including the Missouri Pacific Railroad Booster Hall and the Sunday school building of the St. Paul Episcopal Church. Brothers Sol and David Meyer usually led services, and the Meyer family also assisted in running classes for the children. For a brief time, Rabbi Morris Clark of Pine Bluff traveled to McGehee to lead a Sunday service and assist with religious school.

During a B’nai B’rith meeting in 1946, David Meyer proposed that local Jews build a synagogue, and the motion drew strong support. They formed a congregation named Beth Chayim (House of Life) to serve Jews in the small towns of southeast Arkansas, renaming it Meir Chayim shortly thereafter to honor a local resident, Sergeant Herbert M. Abowitz, who had died in military service during World War II. David Meyer served as the first chairperson of the congregation, which affiliated with the Union of American Hebrew Congregations (later known as the Union for Reform Judaism).

During a B’nai B’rith meeting in 1946, David Meyer proposed that local Jews build a synagogue, and the motion drew strong support. They formed a congregation named Beth Chayim (House of Life) to serve Jews in the small towns of southeast Arkansas, renaming it Meir Chayim shortly thereafter to honor a local resident, Sergeant Herbert M. Abowitz, who had died in military service during World War II. David Meyer served as the first chairperson of the congregation, which affiliated with the Union of American Hebrew Congregations (later known as the Union for Reform Judaism).

Meir Chayim soon undertook the work of constructing a synagogue. They raised money by soliciting donations from Jewish communities around Arkansas and neighboring states, and also by holding a raffle contest that featured a car and a thousand dollar bill among the prizes. The congregation’s building committee did not hire an architect but designed the synagogue themselves after studying other synagogues and churches in the area. Sam Wolchansky—who played a hands-on role in all aspects of the construction process—donated two lots to the congregation, but the congregation opted to sell that land and build on a more appealing site. They eventually purchased two lots from the McGehee Church of Christ.

A shortage of building supplies in the immediate aftermath of World War II delayed construction, and some of the lumber for the building came from trees that were cut down on members’ own property. Wolchansky and other members eventually obtained the necessary materials, and the building was completed in 1947. The official dedication did not take place until 1949, however, at which time Rabbi Ira Sanders of Little Rock delivered the keynote address. Other rabbis attended from Hot Springs, Fort Smith, Pine Bluff, and Belleville, Illinois.

The gothic-style building seated 150 people in its sanctuary and featured ten stained glass windows. Two pairs of tablets depicting the ten commandments came from out-of-town congregations that had previously closed—one from Temple B’nai Sholom in Bastrop, Louisiana, hung in the sanctuary, and one from Temple Beth El Emeth in Camden, Arkansas, hung above the front entrance.

A shortage of building supplies in the immediate aftermath of World War II delayed construction, and some of the lumber for the building came from trees that were cut down on members’ own property. Wolchansky and other members eventually obtained the necessary materials, and the building was completed in 1947. The official dedication did not take place until 1949, however, at which time Rabbi Ira Sanders of Little Rock delivered the keynote address. Other rabbis attended from Hot Springs, Fort Smith, Pine Bluff, and Belleville, Illinois.

The gothic-style building seated 150 people in its sanctuary and featured ten stained glass windows. Two pairs of tablets depicting the ten commandments came from out-of-town congregations that had previously closed—one from Temple B’nai Sholom in Bastrop, Louisiana, hung in the sanctuary, and one from Temple Beth El Emeth in Camden, Arkansas, hung above the front entrance.

Jewish Life and Congregational Leadership

Meir Chayim was never a large congregation, but local leaders maintained an active calendar. Rose Wolff founded a sisterhood in the 1940s. The religious school continued to serve local Jewish children for decades; Else Phillips taught there for thirty-five years. The congregation, like many other rural synagogues, enjoyed a longstanding partnership with Hebrew Union College, which sent rabbinical students to lead regular religious services for more than sixty years.

While a number of people—including members of the Hamburger, Wolff, Phillips, and Pinkus families—provided congregational leadership over the decades, the Tanenbaums also became leaders in regional, national, and international Jewish organizations. Bernard Tanenbaum’s son Jerry, who succeeded his father as the president of the United Dollar Store chain, served for years as the chairman of the board of Henry S. Jacobs Camp in Utica, Mississippi. He also served on the boards of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations (the governing body of American Reform Judaism) and Hebrew Union College (its seminary). In later years he became active with the World Union of Progressive Judaism, which supports Reform Jewish communities across the world. Pat Wise (originally of Columbus, Georgia) married Jerry Tanenbaum in 1955 and became a well-known figure in local and regional organizations herself. She was president of Meir Chayim and regional president of the Women of Reform Judaism, and served on its national board. After Jerry and Pat retired to Hot Springs in 1991, she was elected president of Congregation House of Israel, the first woman to hold the position. She also promoted Reform Judaism abroad through the Union of Jewish Congregations of Latin America (UJCA), which established a foundation in her memory following her death in 2008.

While a number of people—including members of the Hamburger, Wolff, Phillips, and Pinkus families—provided congregational leadership over the decades, the Tanenbaums also became leaders in regional, national, and international Jewish organizations. Bernard Tanenbaum’s son Jerry, who succeeded his father as the president of the United Dollar Store chain, served for years as the chairman of the board of Henry S. Jacobs Camp in Utica, Mississippi. He also served on the boards of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations (the governing body of American Reform Judaism) and Hebrew Union College (its seminary). In later years he became active with the World Union of Progressive Judaism, which supports Reform Jewish communities across the world. Pat Wise (originally of Columbus, Georgia) married Jerry Tanenbaum in 1955 and became a well-known figure in local and regional organizations herself. She was president of Meir Chayim and regional president of the Women of Reform Judaism, and served on its national board. After Jerry and Pat retired to Hot Springs in 1991, she was elected president of Congregation House of Israel, the first woman to hold the position. She also promoted Reform Judaism abroad through the Union of Jewish Congregations of Latin America (UJCA), which established a foundation in her memory following her death in 2008.

A Declining Jewish Population

By the late 20th century, many of the Jewish families of southeast Arkansas began to close their businesses, and younger generations often made their homes in larger cities. In McGehee, the Eagle Store (the Marcus/Lewis family) closed in 1966; the Morris R. Dissent Dry Goods Store closed in 1978; and the Fleisig New York Store closed in 1982. A similar trend played out in Dumas where the Wolff Department Store remained open into the 1990s under the leadership of Haskell Wolff. As elsewhere, the disappearance of small, Jewish-owned retail businesses followed decades of population decline in Desha County and the beginnings of population loss in the towns of Dumas and McGehee, both of which peaked around 1980. At the same time, the rise of discount chains (including the Tanenbaum family’s United Dollar Store) created new competition for small retailers.

According to a news article from 1984, Meir Chayim served a 1,200-square-mile area in which fewer than 100 Jews lived. Membership had fallen to approximately twenty families by that time, and the four Jewish children who belonged to the congregation attended religious school in Greenville, Mississippi (42 miles from McGehee by car).

Meir Chayim continued to operate into the 21st century, holding monthly Friday night services led by visiting student rabbis. The aging membership continued to draw from Desha, Chicot, and Drew counties, but it only included fifteen people by 2007. The remaining members opted to sell their building and liquidate their assets in 2016, and the congregation hosted a deconsecration ceremony in June of that year in order to mark the transition and celebrate their history. The audience included current and former members, non-Jewish locals, and three rabbis. Rabbi Barry Kogan of Hebrew Union College had served as a student rabbi for Meir Chayim in 1968-1969 and remarked on the fond memories that he and other rabbis-in-training had of the local community. Rabbi Debra Kassoff had served the congregation during her tenure at the Institute of Southern Jewish Life and also attended as a representative of Hebrew Union Congregation in Greenville, Mississippi, which received a torah scroll from Meir Chayim. In the typically bittersweet fashion of a small-town synagogue deconsecration, the event also served as a reunion for descendants of local families, and the entire 1968 confirmation class attended the closing ceremony in McGehee.

As of the 2020s only a handful of Jewish residents remain in southeast Arkansas. (Temple Anshe Emeth in Pine Bluff, once the largest congregation in the area, closed its doors just a week before Meir Chayim.) Whereas Jewish residents once played a significant role in local commercial and civic activities, economic conditions no longer support the kind of small-scale retail operations that first drew Jews to the area, and the descendants of southeast Arkansas’s prominent Jewish families have generally moved to larger urban areas. While the Dumas-McGehee Jewish population may stand out for the depth of their civic engagement, the community’s arc from early settlement, growth, and eventual decline mirrors the stories of other small-town Jewish communities in and beyond the South.

Meir Chayim continued to operate into the 21st century, holding monthly Friday night services led by visiting student rabbis. The aging membership continued to draw from Desha, Chicot, and Drew counties, but it only included fifteen people by 2007. The remaining members opted to sell their building and liquidate their assets in 2016, and the congregation hosted a deconsecration ceremony in June of that year in order to mark the transition and celebrate their history. The audience included current and former members, non-Jewish locals, and three rabbis. Rabbi Barry Kogan of Hebrew Union College had served as a student rabbi for Meir Chayim in 1968-1969 and remarked on the fond memories that he and other rabbis-in-training had of the local community. Rabbi Debra Kassoff had served the congregation during her tenure at the Institute of Southern Jewish Life and also attended as a representative of Hebrew Union Congregation in Greenville, Mississippi, which received a torah scroll from Meir Chayim. In the typically bittersweet fashion of a small-town synagogue deconsecration, the event also served as a reunion for descendants of local families, and the entire 1968 confirmation class attended the closing ceremony in McGehee.

As of the 2020s only a handful of Jewish residents remain in southeast Arkansas. (Temple Anshe Emeth in Pine Bluff, once the largest congregation in the area, closed its doors just a week before Meir Chayim.) Whereas Jewish residents once played a significant role in local commercial and civic activities, economic conditions no longer support the kind of small-scale retail operations that first drew Jews to the area, and the descendants of southeast Arkansas’s prominent Jewish families have generally moved to larger urban areas. While the Dumas-McGehee Jewish population may stand out for the depth of their civic engagement, the community’s arc from early settlement, growth, and eventual decline mirrors the stories of other small-town Jewish communities in and beyond the South.

Updated Dec. 2023.