Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Camden, Arkansas

Historical Overview

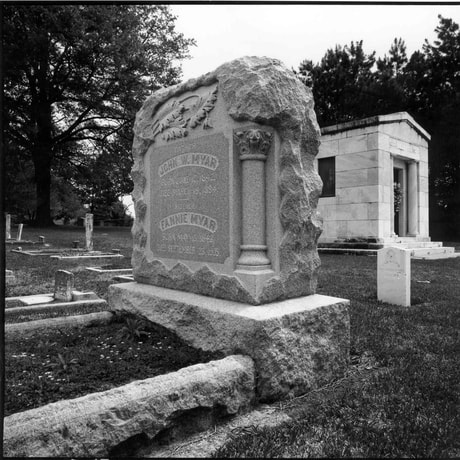

Memorial stone for John and Fannie Myar, c. 1990. Photo by Bill Aron.

Memorial stone for John and Fannie Myar, c. 1990. Photo by Bill Aron.

Camden, the seat of Ouachita County, lies on the Ouachita River in south-central Arkansas, approximately 50 miles north of the Louisiana border. The eventual site of Camden served as a point of trade and cultural exchange for American Indian groups, and French settlers established a trading post called Ecore a Fabri (Fabre’s Bluff) there in the 18th century. By the time of the town’s incorporation in 1844, Camden (renamed in 1842) had become a commercial hub for the surrounding area, as steamboat travel to and from New Orleans terminated at the local riverport. In 1860, Camden was the second largest city in Arkansas, with 2,219 residents, but it never became a large town, despite its early promise.

Jewish migrants found their way to Camden and surrounding settlements in the mid-1840s, where they first engaged in mercantile trade and soon became deeply involved in the agricultural economy, which centered on cotton produced by enslaved Black people. By 1870, a small group of local Jews established a local congregation that served as the center of local Jewish life into the early 20th century. While several Jewish families played important roles in Camden’s development and civic life, the local Jewish population was never large, and the congregation ceased regular activity by 1930 or so.

Jewish migrants found their way to Camden and surrounding settlements in the mid-1840s, where they first engaged in mercantile trade and soon became deeply involved in the agricultural economy, which centered on cotton produced by enslaved Black people. By 1870, a small group of local Jews established a local congregation that served as the center of local Jewish life into the early 20th century. While several Jewish families played important roles in Camden’s development and civic life, the local Jewish population was never large, and the congregation ceased regular activity by 1930 or so.

Early Jewish Settlers

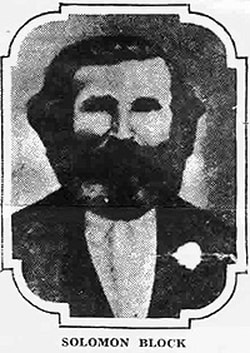

At least one Jewish settler, Solomon Block, arrived in Camden before 1850. A native of Bohemia, Block did well for himself and later went into business with Edward Feibleman. The two purchased a large sugar plantation in St. Mary’s Parish, Louisiana, which lies due south of Ouachita County. The 1860 U.S. Census indicates that Block enslaved 8 individuals in Camden; depending on when Block and Feibleman purchased their Louisiana lands, they may also have relied on enslaved labor there as well.

Meyer (or Myar) Berg was another early Jewish arrival to Camden. He and his wife, Gette, opened M. Berg Mercantile in or around 1856, and some of their descendants remain in Camden as of the early 21st century. Like most of their Jewish contemporaries, Meyer and Gette Berg came from German territories; the 1880 U.S. Census lists his birthplace as Prussia and hers as Bavaria. Around 24 Jewish men—some with families and some single—lived in Camden by 1860.

After the Civil War broke out in 1861, several Jewish men from Camden and Ouachita County joined the Confederate Army. David Felsenthal, for example, reportedly closed his mercantile business in order to volunteer for service, and lost most of his property as a result. After his capture by the Union Army, his older brother (Rabbi Bernard Felsenthal of Chicago) helped secure David’s release from a military prison, after which he returned to Camden. Other Jewish Confederates from the area included Sam Winter and Henry Myar. Despite their apparent support for the cause of slavery, census records suggest that only a minority of Camden Jews enslaved Black workers at the outbreak of the war.

After the Civil War broke out in 1861, several Jewish men from Camden and Ouachita County joined the Confederate Army. David Felsenthal, for example, reportedly closed his mercantile business in order to volunteer for service, and lost most of his property as a result. After his capture by the Union Army, his older brother (Rabbi Bernard Felsenthal of Chicago) helped secure David’s release from a military prison, after which he returned to Camden. Other Jewish Confederates from the area included Sam Winter and Henry Myar. Despite their apparent support for the cause of slavery, census records suggest that only a minority of Camden Jews enslaved Black workers at the outbreak of the war.

An Emerging Jewish Community

As in other areas of the South, the economic restructuring that occurred in the post-Civil War period attracted new Jewish migrants, which spurred the creation of Jewish organizations. Jews in Camden and Ouachita County began to establish their own institutions in 1865, beginning with a Hebrew Benevolent Society. By 1870 the group had purchased land for a cemetery. Local Jews also opened a Sunday school and prayed together in services led by merchant Aaron Freidheim.

In December 1870, 24 Jewish men officially founded a congregation, Beth El Emeth (House of God of Truth). Its first officers were: Solomon Block, president; John Lazarus, secretary; Moses Winter, treasurer; and Edward Feibelman, Sol Levy, and David Felsenthal, trustees. All but three of these 24 founders were immigrants; most were from the German states and owned retail stores. A handful of the founders, such as Solomon Block, Meyer Berg, and Henry Myar, were very successful businessmen and used their significant financial means to support the fledgling congregation.

Although most of the founders had been raised Orthodox, Beth El Emeth was founded as a Reform congregation. They soon joined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, the central organization of Reform Judaism in the United States. As merchants, congregation members were unable to close their stores on Saturday, the biggest business day of the week, and thus had to adjust their religious practice to fit their new environment. Additionally, it would have been extremely difficult for Camden Jews to obtain kosher meat on a regular basis.

Members of Beth El Emeth had discussed their intention to construct a synagogue at their founding meeting, and they broke ground on the corner of Adams Avenue and Jackson Street within two years. The small congregation also hired a full-time spiritual leader in 1872, Rabbi M. Sukenheimer from Chicago. Rabbi Sukenheimer presided over the formal dedication of the synagogue in October 1873, an event which attracted congregants and non-Jewish community members alike. During the ceremony, Sukenheimer spoke about the importance of religious liberty and toleration in America, contrasting it with the repression that Jews experienced elsewhere in the world.

The synagogue was a tall frame building with a brick foundation and a high ceiling. Two winding staircases led from the front entrance into the main sanctuary, which sat 150 people. In 1887 the congregation added a lower-level meeting room, which was used for Sunday School classes. According to member Adolph Felsenthal, “in design, it was crude perhaps, but with a simple austerity of plan that reflects the sober minded character of the men who first provided it.” The building cost the congregation $8,000, which they paid in full by the time of the dedication. Camden Jews’ ability to construct even a small synagogue without significant debt reflected the tremendous economic success of its most affluent members.

Rabbi Sukenheimer departed in 1874, and Beth El Emeth continued to employ rabbis for short stints in subsequent years. Their most notable clergyman was Rabbi Nachman Benson, who proved popular and memorable, despite staying for only a year. In addition to leading weekly services, Rabbi Benson ran a day school at the temple since there was no public school system in town at the time. Known as a charismatic speaker, his Friday night sermons attracted non-Jews to the temple. Benson left Camden to serve a congregation in Macon, Georgia, and later returned to Arkansas to lead B’nai Israel in Little Rock.

Camden Jews also maintained family and social links to other Jewish communities in the state. An 1898 newspaper article indicates that Claudia and Hannah Myar, daughters of Henry and Lena Myar, attended a ball held by the Young Men’s Hebrew Association of Pine Bluff; Claudia and a younger sister, Gertrude, both married into Pine Bluff families. A decade later, Congregation Beth El Emeth participated in the Arkansas Conference of Jewish Religious School Teachers, hosted by B’nai Israel of Little Rock and drawing representatives from Pine Bluff, Fort Smith, Helena, and Hot Springs.

Although most of the founders had been raised Orthodox, Beth El Emeth was founded as a Reform congregation. They soon joined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, the central organization of Reform Judaism in the United States. As merchants, congregation members were unable to close their stores on Saturday, the biggest business day of the week, and thus had to adjust their religious practice to fit their new environment. Additionally, it would have been extremely difficult for Camden Jews to obtain kosher meat on a regular basis.

Members of Beth El Emeth had discussed their intention to construct a synagogue at their founding meeting, and they broke ground on the corner of Adams Avenue and Jackson Street within two years. The small congregation also hired a full-time spiritual leader in 1872, Rabbi M. Sukenheimer from Chicago. Rabbi Sukenheimer presided over the formal dedication of the synagogue in October 1873, an event which attracted congregants and non-Jewish community members alike. During the ceremony, Sukenheimer spoke about the importance of religious liberty and toleration in America, contrasting it with the repression that Jews experienced elsewhere in the world.

The synagogue was a tall frame building with a brick foundation and a high ceiling. Two winding staircases led from the front entrance into the main sanctuary, which sat 150 people. In 1887 the congregation added a lower-level meeting room, which was used for Sunday School classes. According to member Adolph Felsenthal, “in design, it was crude perhaps, but with a simple austerity of plan that reflects the sober minded character of the men who first provided it.” The building cost the congregation $8,000, which they paid in full by the time of the dedication. Camden Jews’ ability to construct even a small synagogue without significant debt reflected the tremendous economic success of its most affluent members.

Rabbi Sukenheimer departed in 1874, and Beth El Emeth continued to employ rabbis for short stints in subsequent years. Their most notable clergyman was Rabbi Nachman Benson, who proved popular and memorable, despite staying for only a year. In addition to leading weekly services, Rabbi Benson ran a day school at the temple since there was no public school system in town at the time. Known as a charismatic speaker, his Friday night sermons attracted non-Jews to the temple. Benson left Camden to serve a congregation in Macon, Georgia, and later returned to Arkansas to lead B’nai Israel in Little Rock.

Camden Jews also maintained family and social links to other Jewish communities in the state. An 1898 newspaper article indicates that Claudia and Hannah Myar, daughters of Henry and Lena Myar, attended a ball held by the Young Men’s Hebrew Association of Pine Bluff; Claudia and a younger sister, Gertrude, both married into Pine Bluff families. A decade later, Congregation Beth El Emeth participated in the Arkansas Conference of Jewish Religious School Teachers, hosted by B’nai Israel of Little Rock and drawing representatives from Pine Bluff, Fort Smith, Helena, and Hot Springs.

Business and Civic Life

Memoirs by Camden Jews and general local histories regularly note the prominent roles played by the area’s most successful Jewish families. Early arrivals such as Solomon Block and Meyer Berg were quite visible in the public life of the town. Block, for example, led the local school board and opposed mandatory Bible readings in the public schools. Jewish women also participated in non-Jewish social and civic organizations; Lena Myar, wife of Henry Myar, participated in Camden sewing circles and held a leadership position in the local chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, in addition to her membership in the Beth El Emeth Ladies Aid Society. Nathan and Louis Bry found their way to Camden after the Civil War and opened the first modern department store in south Arkansas, with such innovations as cash-only sales, clearly marked prices, and women clerks. By the early 1890s they had hired managers to run the store and relocated to St. Louis.

A welcome sign in Felsenthal, Arkansas, founded by Adolph Felsenthal and his brothers in the early 20th century. Photograph by Emily Williams, 2023.

A welcome sign in Felsenthal, Arkansas, founded by Adolph Felsenthal and his brothers in the early 20th century. Photograph by Emily Williams, 2023.

Beth El Emeth itself held a significant place in local life. White, non-Jewish residents attended events there on a number of occasions, and the congregation made its synagogue building available (at no charge) to multiple white, Christian congregations when their churches were under construction. In later years, when the congregation was without a building, Camden churches reciprocated by hosting Jewish funerals.

As in other parts of Arkansas and the South, white supremacy dictated the structure of economic and social life in Camden and Ouachita County, and several documented instances of racist, anti-Black violence took place there. While the Ku Klux Klan grew powerful in 1920s Arkansas, however, the white elite of Camden managed to keep the organization out of local elected positions. Leo Berg, the son of Meyer Berg, served as mayor during the period, which reflected the general acceptance of Jews into white society.

Other Jewish men who held public office included Adolph Felsenthal (county assessor, early 20th century), Abe Lazarus (longtime school board member, early 20th century), and Leonard Stern (alderman and judge, early and mid-20th century). All three of these officeholders, as well as Leo Berg, were the sons of 19th-century immigrants who had settled in Camden.

Adolph Felsenthal also gained recognition for promoting the early-20th-century development of the Ouachita River, including engineering projects that assured year-round navigability and led to the construction of dams and hydroelectric power plants. He had a direct financial stake in such advances due to his involvement in the south Arkansas lumber industry. He and three brothers established the Felsenthal Land and Timber Company around 1900, and shortly afterward they founded Felsenthal, Arkansas, a company town located on the Ouachita River in Union County.

As in other parts of Arkansas and the South, white supremacy dictated the structure of economic and social life in Camden and Ouachita County, and several documented instances of racist, anti-Black violence took place there. While the Ku Klux Klan grew powerful in 1920s Arkansas, however, the white elite of Camden managed to keep the organization out of local elected positions. Leo Berg, the son of Meyer Berg, served as mayor during the period, which reflected the general acceptance of Jews into white society.

Other Jewish men who held public office included Adolph Felsenthal (county assessor, early 20th century), Abe Lazarus (longtime school board member, early 20th century), and Leonard Stern (alderman and judge, early and mid-20th century). All three of these officeholders, as well as Leo Berg, were the sons of 19th-century immigrants who had settled in Camden.

Adolph Felsenthal also gained recognition for promoting the early-20th-century development of the Ouachita River, including engineering projects that assured year-round navigability and led to the construction of dams and hydroelectric power plants. He had a direct financial stake in such advances due to his involvement in the south Arkansas lumber industry. He and three brothers established the Felsenthal Land and Timber Company around 1900, and shortly afterward they founded Felsenthal, Arkansas, a company town located on the Ouachita River in Union County.

The 20th Century

Although Camden Jews enjoyed a high level of acceptance and, in several cases, experienced significant economic success, the community did not continue to grow in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Whereas new Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe bolstered Jewish populations in many American small towns, Camden only attracted a handful of newcomers. Frank and Yetta Phillips opened a small dry goods store in Camden from approximately 1903 to 1930, and Mose and Ida Zavelo (U.S.-born children of East European immigrants) opened a ladies’ clothing shop in the 1920s which was continued by their son Burton into the 1960s.

The membership of Beth El Emeth likely peaked in the late 19th century. An estimated 86 Jews lived in Camden in 1878, and that number dwindled to 60 or so by 1937. In the meantime, the congregation claimed no more than 13 member families during the early 20th century. The small community struggled to attract full-time rabbinical services, and they often relied on student rabbis from Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati. (One student rabbi, Samuel Goldenson, met his future wife Claudia Myar while staying with her family; he went on to serve at Temple Emanu-El of New York City, a nationally renowned congregation.) By 1919 Beth El Emeth dispensed with weekly services and met only on Jewish holidays.

The southern Arkansas portion of the West Gulf Coastal Plain never drew heavy industry and does not boast the rich soil of the Arkansas Delta. As a result, a number of other Arkansas cities surpassed Camden in population and economic growth. The opening of a new papermill and the discovery of oil in Ouachita County did offer some new opportunities in the 1920s, but even the general population growth that took place from 1920 to 1950 could not reinvigorate the local Jewish community.

With little hope that the Camden Jewish population would grow in the future, the members of Beth El Emeth decided to sell their aging synagogue building in 1927. One third of the sale proceeds went to a perpetual care fund for their synagogue. Henry Berg paid for the construction of a modest new synagogue on Clifton Street in the late 1930s, but it did not enjoy regular use. That building was also sold eventually and converted to a private residence, with proceeds once again adding to the cemetery fund.

By the 1990s only one Jewish family remained in Camden, and the congregation had long since dissolved. The town’s few remaining Jews made the long drive to Little Rock for weekly Religious School services. In the early 21st century, the most visible marker of Camden’s once-prominent Jewish community is the Hebrew Rest Cemetery.

The membership of Beth El Emeth likely peaked in the late 19th century. An estimated 86 Jews lived in Camden in 1878, and that number dwindled to 60 or so by 1937. In the meantime, the congregation claimed no more than 13 member families during the early 20th century. The small community struggled to attract full-time rabbinical services, and they often relied on student rabbis from Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati. (One student rabbi, Samuel Goldenson, met his future wife Claudia Myar while staying with her family; he went on to serve at Temple Emanu-El of New York City, a nationally renowned congregation.) By 1919 Beth El Emeth dispensed with weekly services and met only on Jewish holidays.

The southern Arkansas portion of the West Gulf Coastal Plain never drew heavy industry and does not boast the rich soil of the Arkansas Delta. As a result, a number of other Arkansas cities surpassed Camden in population and economic growth. The opening of a new papermill and the discovery of oil in Ouachita County did offer some new opportunities in the 1920s, but even the general population growth that took place from 1920 to 1950 could not reinvigorate the local Jewish community.

With little hope that the Camden Jewish population would grow in the future, the members of Beth El Emeth decided to sell their aging synagogue building in 1927. One third of the sale proceeds went to a perpetual care fund for their synagogue. Henry Berg paid for the construction of a modest new synagogue on Clifton Street in the late 1930s, but it did not enjoy regular use. That building was also sold eventually and converted to a private residence, with proceeds once again adding to the cemetery fund.

By the 1990s only one Jewish family remained in Camden, and the congregation had long since dissolved. The town’s few remaining Jews made the long drive to Little Rock for weekly Religious School services. In the early 21st century, the most visible marker of Camden’s once-prominent Jewish community is the Hebrew Rest Cemetery.