Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Alabama

Overview >> Alabama

The first Jew to settle in Alabama was Abraham Mordecai, who arrived in Montgomery County in 1785. A colorful character who thought the Native Americans he encountered were one of the lost tribes of Israel, Mordecai established a post on the banks of the Alabama River to trade with the Creek and Chickasaw tribes. This post eventually grew into the state capital of Montgomery. Mordecai spent several decades living among these tribes, often acting as the liaison between the natives and the growing number of American settlers in the area. He even married a Creek woman. Mordecai’s status as a Jewish pioneer led to a life of isolation, as no Jewish community existed in the area yet. By the end of his life, he lived alone as a pauper in an abandoned Indian hut on the outskirts of Montgomery. Some of his few possessions at the time included his own coffin, which he had built himself, and an old Hebrew bible.

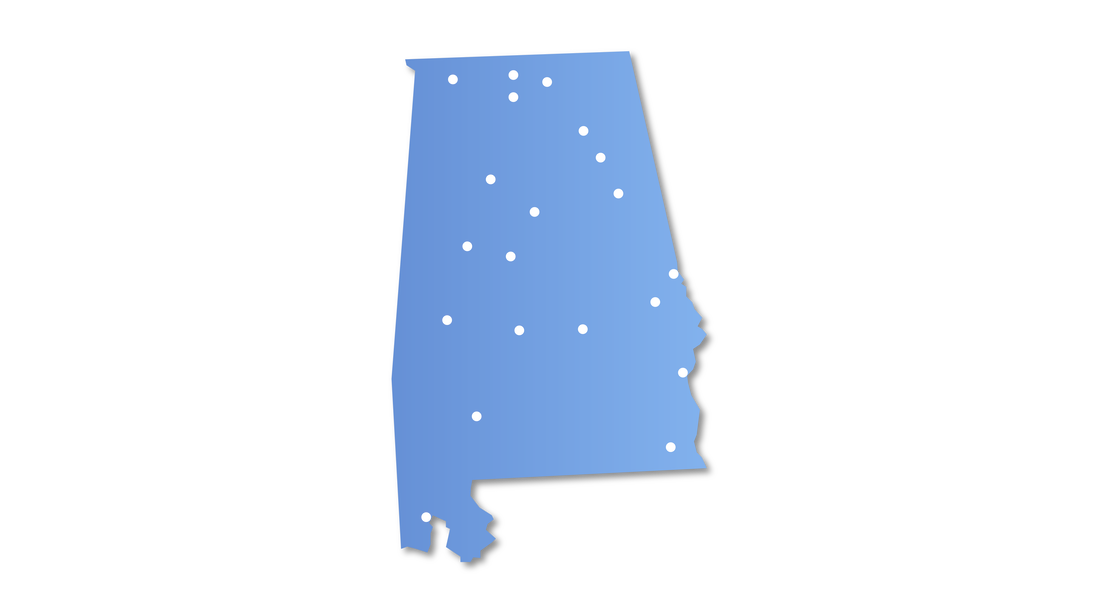

Despite the pioneering exploits of Mordecai, Jews did not begin to settle in Alabama in significant numbers until the 1830s. The first permanent Jewish community was located in the port city of Mobile, which attracted Jewish immigrants as early as the 1820s. By the 1840s, Jewish immigrants from the German states were living in cotton market towns like Montgomery, Claiborne, Eufaula, Selma, and Demopolis. Soon after the Civil War, growing numbers of Jews settled in Decatur, Athens, Huntsville, Opelika, Tuscaloosa, and Dothan. As coal mining and iron production arose in the eastern part of the state after the war, Jewish merchants settled in the towns and cities that sprouted in its wake, including Birmingham, Bessemer, West Blocton, Anniston, Jasper, and Gadsden. Perhaps the most unusual Jewish community in state was founded on Sand Mountain in 1903. Led by Jacob Daneman, a group of Jewish immigrants established a socialist farming commune in the northeast corner of the state, though the group struggled for survival for two years before disbanding in 1905.

The first Jewish congregation in Alabama was established in Mobile in 1844. Later congregations were founded in Claiborne (1846), Montgomery (1852), Demopolis (1858), Lanett (1859), Selma (left - 1867), Eufaula (1867), Huntsville (1876), Birmingham (1882), Anniston (1888), Bessemer (1892), Tuscaloosa (1903), West Blocton (1905), Tri-Cities (1906), Gadsden (1908), Jasper (1913), Decatur (1916), Athens (1916), Dothan (1928), and Auburn (1989). Most of the early congregations eventually adopted Reform Judaism, though in larger cities like Montgomery, Birmingham, and Mobile, Eastern European Jewish immigrants established their own separate traditional congregations. A significant number of Sephardic Jews from the Isle of Rhodes settled in Montgomery in the early 20th century and established the state’s only Sephardic congregation.

The first Jewish congregation in Alabama was established in Mobile in 1844. Later congregations were founded in Claiborne (1846), Montgomery (1852), Demopolis (1858), Lanett (1859), Selma (left - 1867), Eufaula (1867), Huntsville (1876), Birmingham (1882), Anniston (1888), Bessemer (1892), Tuscaloosa (1903), West Blocton (1905), Tri-Cities (1906), Gadsden (1908), Jasper (1913), Decatur (1916), Athens (1916), Dothan (1928), and Auburn (1989). Most of the early congregations eventually adopted Reform Judaism, though in larger cities like Montgomery, Birmingham, and Mobile, Eastern European Jewish immigrants established their own separate traditional congregations. A significant number of Sephardic Jews from the Isle of Rhodes settled in Montgomery in the early 20th century and established the state’s only Sephardic congregation.

Alabama Jews have played an important role in the state’s development. Prior to the Civil War, Emanuel and Mayer Lehman moved into cotton brokering after they began accepting cotton as payment for merchandise at their dry goods store in Montgomery. Later, both brothers moved to New York, where their cotton trading form, Lehman Brothers, grew into one of the most successful investment banks in the country. Another pair of brothers, Alfred and Mordecai Moses, moved from Charleston, South Carolina to Montgomery, where they both became important civic leaders. Mordecai won election as mayor in 1875 as a Democrat, ending the political reign of Reconstruction in Montgomery. The brothers later launched a plan to build a new industrial town on the banks of the Tennessee River across from Florence. Naming the city Sheffield, Alfred sought to turn it into a new industrial center, though their venture soon went bankrupt. Sheffield did not emerge as a thriving industrial town until after the turn of the century.

Mordecai Moses was just one of a handful of Jews who served as mayor of their town; Jews served as mayors of Demopolis, Madison, Mobile, Montgomery, Pollard, Selma, and Sheffield. Perhaps the most notable Alabama Jew to be elected to public office was Philip Phillips (left). After serving in the Alabama State Legislature, Phillips was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives from Mobile in 1852. Though he supported slavery, Philips was also a Unionist and remained in Washington after secession, becoming a successful lawyer after the Civil War. His wife Eugenia was a staunch Confederate, and was even briefly imprisoned for espionage against the United States.

Alabama Jews have long been active civic leaders in the state. Samuel Ullman (right) came to Birmingham from Natchez, Mississippi and quickly got involved in public education, joining the local board of education. In 1899, Ullman persuaded the city to build its first permanent public high school. He was also a strong advocate of education for the city’s African American population, pushing the city to build a high school for black students in 1900. Burghard and Sigfried Steiner opened a successful bank in Birmingham in 1887; during the Panic of 1893, they saved the city from bankruptcy with their “Steiner Plan” in which they underwrote the interest on the city’s bonds.

Alabama Jews have long been active civic leaders in the state. Samuel Ullman (right) came to Birmingham from Natchez, Mississippi and quickly got involved in public education, joining the local board of education. In 1899, Ullman persuaded the city to build its first permanent public high school. He was also a strong advocate of education for the city’s African American population, pushing the city to build a high school for black students in 1900. Burghard and Sigfried Steiner opened a successful bank in Birmingham in 1887; during the Panic of 1893, they saved the city from bankruptcy with their “Steiner Plan” in which they underwrote the interest on the city’s bonds.

This tradition of community involvement has continued through recent times. Rubin Hanan was an immigrant from Rhodes who became a leader of Montgomery’s strong Sephardic community. He was very politically active, working on the staffs of three different Alabama governors in the mid 20th century. Hanan became an activist for the elderly and was appointed to the Advisory Committee for Older Americans by President Lyndon Johnson. Mayer “Bubba” Mitchell was a successful real estate developer in Mobile who became a tremendous benefactor of the University of South Alabama and other local institutions as well as an important national leader of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee.

The Jewish population of Alabama peaked in 1927 at 12,891 people. Since then, the state’s Jewish community has slowly shrunk, and today numbers around 9,000. Over 90% of the state’s Jews are concentrated in Alabama’s four largest cities, including Birmingham (5,300 Jews), Montgomery (1,200), Mobile (1,100), and Huntsville (750). Birmingham, with its multiple congregations, Jewish Community Center, and Jewish Day School, remains the largest and most active Jewish community in the state. Smaller Jewish communities like Gadsden, Anniston, Jasper, and Demopolis have seen sharp declines in their Jewish populations over the past several decades. Other Jewish communities like Tuscaloosa and Dothan have fought these demographic trends by making strong efforts to attract Jews to their cities. Working with the University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa’s Jewish community is building a new synagogue on campus while Dothan’s Jewish community is offering financial incentives for Jewish families to move to the city. Despite these efforts, Alabama’s Jewish population will likely follow the regional trend of concentrating in the larger cities while the small Jewish communities in the state continue to struggle.

The Jewish population of Alabama peaked in 1927 at 12,891 people. Since then, the state’s Jewish community has slowly shrunk, and today numbers around 9,000. Over 90% of the state’s Jews are concentrated in Alabama’s four largest cities, including Birmingham (5,300 Jews), Montgomery (1,200), Mobile (1,100), and Huntsville (750). Birmingham, with its multiple congregations, Jewish Community Center, and Jewish Day School, remains the largest and most active Jewish community in the state. Smaller Jewish communities like Gadsden, Anniston, Jasper, and Demopolis have seen sharp declines in their Jewish populations over the past several decades. Other Jewish communities like Tuscaloosa and Dothan have fought these demographic trends by making strong efforts to attract Jews to their cities. Working with the University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa’s Jewish community is building a new synagogue on campus while Dothan’s Jewish community is offering financial incentives for Jewish families to move to the city. Despite these efforts, Alabama’s Jewish population will likely follow the regional trend of concentrating in the larger cities while the small Jewish communities in the state continue to struggle.