Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Montgomery, Alabama

Historical Overview

|

Montgomery was incorporated in 1819 and has been the capital of Alabama since 1846. Jews have were part of the city's history even before its incorporation, with the first Jew arriving in the area in 1785. Starting with a single Jewish trader and growing to an entire community, Jews have played an important part in the development of Montgomery and its economic and civic life.

|

Stories of the Jewish Community in Montgomery

Abraham Mordecai and the Lost Tribe of Israel

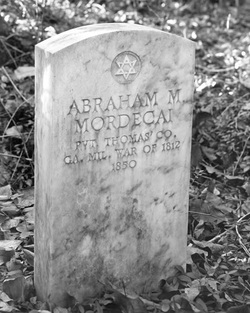

In the history of encounters between Europeans and indigenous groups of the New World, there is persistent trend of misinterpretation and cultural projection. When Columbus landed on Hispaniola he was certain the Arawak people were some tribal group of the Indian Ocean. Supposedly, when the Aztecs saw Spanish conquistador Hernan Cortez they believed him to be their god Quetzalcoatl. And when Abraham Mordecai first settled in Montgomery County in 1785, he was certain that he had discovered a Lost Tribe of Israel. When he spoke to the Creek and Chickasaw people, he fervently believed that one day he would understand their language, which he assumed was a derivation of Hebrew.

“Muccose,” “Old Mordecai,” and “the Little Chief”, were among the names given to Montgomery County’s infamous first Euro-American settler, but before he was any of those he was simply born as Abraham in 1750, the son of Jewish merchants in Pennsylvania. In his twenties, he served in the War for Independence. At the war’s end, he ventured into the unsettled west of Alabama. He worked along the Pensacola Trading Trail, running missions for trading companies, and traveling with a horde of pack ponies. In 1785, Abraham eventually came to the western bank of the Alabama River, previously untouched by European settlers, where he established his solitary trading post in Creek and Chickasaw territory. The local tribes were not immediately hostile to Mordecai. They must have viewed him quizzically as he greeted them with a hearty “shalom,” expecting them to understand. Apparently, Mordecai thought he recognized Hebrew words in the rituals of the Creek corn festival. He was convinced they were praying to his very same God.

Mordecai lived with the Creek, Chickasaw, and Coosawda for nearly twenty years. He conducted trade in furs, hickory, and nut oil, paddling his canoe as far as Mobile and New Orleans. He brought the first cotton gin to Alabama. Often, Mordecai acted as a liaison between the tribes and white settlements in the east, negotiating ransom for captives or trade deals. Though he lived in relative stability with the native groups, his time there was not without a skirmish or two. In an oft-recounted tale, Chief Towerculla of the Coosawda tribe appeared outside of Mordecai’s cabin with twelve of his soldiers one day in 1802. They were angry. In one version of the story, Mordecai had upset the tribe by trying to seduce an already married woman. In another, Mordecai had trampled over Coosawda corn fields in an attempt to seize more land for himself. For whichever reason, Chief Towerculla and his soldiers surrounded him, pinned him to the ground, beat him with sticks, and cut off his ear. They also raided his home and destroyed the cotton gin.

Despite the occasional confrontation, Mordecai did live more-or-less peacefully with the local tribes, learning their language and customs. Eventually, he was successful in marrying a Creek woman. Mordecai's wife shared his home for several years, until Andrew Jackson's Indian forced her to travel the Trail of Tears and relocate to western unorganized territory in 1836. Not long after the violent rupture of his marriage, Mordecai moved away from his original settlement. With the purging of Alabama’s native groups, more and more white settlers were struck with “Alabama Fever” and moved to Montgomery to take advantage of its strategic location on the Alabama River. By 1846, it was a thriving community and the site of Mordecai’s original trading post became Alabama’s state capital.

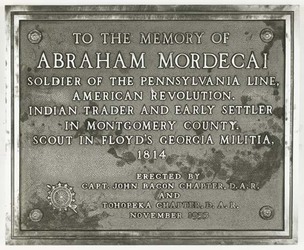

In 1847, Albert James Pickett, a journalist from Montgomery, discovered Mordecai in a remote mountain cabin near Dudleyville. In his old age Mordecai had become increasingly eccentric, having built his own coffin on the floor next to his bed. Relishing the company of another human being, he told Pickett all about his life as a trader living among the strange, lost tribe of Israel. Mordecai died at the age of ninety-nine, three years after that final interview. He was buried in the coffin he built himself. The Montgomery Evening News proposed the construction of a monument to the Little Chief, who they deemed “the cradle rocker of Montgomery’s infancy.” The Daughters of the American Revolution erected a small plaque in Dudleyville that stands to this day.

In the history of encounters between Europeans and indigenous groups of the New World, there is persistent trend of misinterpretation and cultural projection. When Columbus landed on Hispaniola he was certain the Arawak people were some tribal group of the Indian Ocean. Supposedly, when the Aztecs saw Spanish conquistador Hernan Cortez they believed him to be their god Quetzalcoatl. And when Abraham Mordecai first settled in Montgomery County in 1785, he was certain that he had discovered a Lost Tribe of Israel. When he spoke to the Creek and Chickasaw people, he fervently believed that one day he would understand their language, which he assumed was a derivation of Hebrew.

“Muccose,” “Old Mordecai,” and “the Little Chief”, were among the names given to Montgomery County’s infamous first Euro-American settler, but before he was any of those he was simply born as Abraham in 1750, the son of Jewish merchants in Pennsylvania. In his twenties, he served in the War for Independence. At the war’s end, he ventured into the unsettled west of Alabama. He worked along the Pensacola Trading Trail, running missions for trading companies, and traveling with a horde of pack ponies. In 1785, Abraham eventually came to the western bank of the Alabama River, previously untouched by European settlers, where he established his solitary trading post in Creek and Chickasaw territory. The local tribes were not immediately hostile to Mordecai. They must have viewed him quizzically as he greeted them with a hearty “shalom,” expecting them to understand. Apparently, Mordecai thought he recognized Hebrew words in the rituals of the Creek corn festival. He was convinced they were praying to his very same God.

Mordecai lived with the Creek, Chickasaw, and Coosawda for nearly twenty years. He conducted trade in furs, hickory, and nut oil, paddling his canoe as far as Mobile and New Orleans. He brought the first cotton gin to Alabama. Often, Mordecai acted as a liaison between the tribes and white settlements in the east, negotiating ransom for captives or trade deals. Though he lived in relative stability with the native groups, his time there was not without a skirmish or two. In an oft-recounted tale, Chief Towerculla of the Coosawda tribe appeared outside of Mordecai’s cabin with twelve of his soldiers one day in 1802. They were angry. In one version of the story, Mordecai had upset the tribe by trying to seduce an already married woman. In another, Mordecai had trampled over Coosawda corn fields in an attempt to seize more land for himself. For whichever reason, Chief Towerculla and his soldiers surrounded him, pinned him to the ground, beat him with sticks, and cut off his ear. They also raided his home and destroyed the cotton gin.

Despite the occasional confrontation, Mordecai did live more-or-less peacefully with the local tribes, learning their language and customs. Eventually, he was successful in marrying a Creek woman. Mordecai's wife shared his home for several years, until Andrew Jackson's Indian forced her to travel the Trail of Tears and relocate to western unorganized territory in 1836. Not long after the violent rupture of his marriage, Mordecai moved away from his original settlement. With the purging of Alabama’s native groups, more and more white settlers were struck with “Alabama Fever” and moved to Montgomery to take advantage of its strategic location on the Alabama River. By 1846, it was a thriving community and the site of Mordecai’s original trading post became Alabama’s state capital.

In 1847, Albert James Pickett, a journalist from Montgomery, discovered Mordecai in a remote mountain cabin near Dudleyville. In his old age Mordecai had become increasingly eccentric, having built his own coffin on the floor next to his bed. Relishing the company of another human being, he told Pickett all about his life as a trader living among the strange, lost tribe of Israel. Mordecai died at the age of ninety-nine, three years after that final interview. He was buried in the coffin he built himself. The Montgomery Evening News proposed the construction of a monument to the Little Chief, who they deemed “the cradle rocker of Montgomery’s infancy.” The Daughters of the American Revolution erected a small plaque in Dudleyville that stands to this day.

A Growing Community

As Montgomery began to blossom as a bustling capital, it attracted a growing immigrant population. Among them were a group of Jewish immigrants from Bavaria. The very first Jew in Montgomery was Jacob Sacerdote, who was quick to found a restaurant at Court Square, the heart of the burgeoning downtown. Soon to follow were a series of families that would come to define and exemplify the presence of Jews in Montgomery.

Bavarian law limited the amount of Jews in any given town and required a permit for Jewish residents. Thus, when Henry, Emanuel, and Mayer Lehman’s oldest brother received a permit to stay in their village, the three younger Lehmans had little future in their homeland. Henry arrived in Montgomery in 1844, immediately establishing a small general store, and was able to save up enough money for Emanuel to join him in 1847 and Mayer to follow in 1848. Because the majority of their customers were farmers, they traded consumer goods for cotton in their store. Eventually, Lehman Brothers the general store transformed into Lehman Brothers the cotton brokerage firm, and over the course of its history, Lehman Brothers would become a leader in global finance.

The Weil brothers, Josiah, Heinrich, and Jacob, came from Oberlustadt early in the 1840s and took part in the booming cotton trade. Samuel Leopold Schloss came around the same time and started off as a grocer. Soon there after, Jacob Kohn came from Bavaria and brought his old world shoe making skills with him. These immigrants, mostly young and fresh from their homelands, saw the need to establish some sort of organization to provide services to the fledgling Jewish community. In November of 1846, while meeting at the home of the Gans brothers, the Jews of Montgomery formed Chevra Mevacher Cholim, a society for administering to the sick and preparing the dead for burial.

As Montgomery began to blossom as a bustling capital, it attracted a growing immigrant population. Among them were a group of Jewish immigrants from Bavaria. The very first Jew in Montgomery was Jacob Sacerdote, who was quick to found a restaurant at Court Square, the heart of the burgeoning downtown. Soon to follow were a series of families that would come to define and exemplify the presence of Jews in Montgomery.

Bavarian law limited the amount of Jews in any given town and required a permit for Jewish residents. Thus, when Henry, Emanuel, and Mayer Lehman’s oldest brother received a permit to stay in their village, the three younger Lehmans had little future in their homeland. Henry arrived in Montgomery in 1844, immediately establishing a small general store, and was able to save up enough money for Emanuel to join him in 1847 and Mayer to follow in 1848. Because the majority of their customers were farmers, they traded consumer goods for cotton in their store. Eventually, Lehman Brothers the general store transformed into Lehman Brothers the cotton brokerage firm, and over the course of its history, Lehman Brothers would become a leader in global finance.

The Weil brothers, Josiah, Heinrich, and Jacob, came from Oberlustadt early in the 1840s and took part in the booming cotton trade. Samuel Leopold Schloss came around the same time and started off as a grocer. Soon there after, Jacob Kohn came from Bavaria and brought his old world shoe making skills with him. These immigrants, mostly young and fresh from their homelands, saw the need to establish some sort of organization to provide services to the fledgling Jewish community. In November of 1846, while meeting at the home of the Gans brothers, the Jews of Montgomery formed Chevra Mevacher Cholim, a society for administering to the sick and preparing the dead for burial.

Organized Jewish Life in Montgomery

With twelve families in all, the Jews of Montgomery organized Congregation Kahl Montgomery on May 6, 1849. At first they worshiped in congregants' homes, organizing lay-led, Orthodox services, but as their numbers expanded they began to rent out Lyceum Hall on Dexter Avenue. Jews from neighboring towns came to Montgomery weekly to participate in services. Gentiles, never having seen Jews or their religious practices before, came to watch the ceremonies with an awed curiosity.

Kahl Montgomery drafted an official charter in 1852, and they continued to practice in rented space, without the resources to buy their own building. However, when wealthy New Orleans philanthropist Judah Touro died in 1858, he left money for Jewish congregations around the country, including Kahl Montgomery, which received $2,000 to build a synagogue. With this exciting development, Josiah Weil became Kahl Montgomery’s first president and established a committee to plan for the construction of a new building. In 1859, the group voted to purchase a plot on the corner of Church and Catoma Street.

The Jewish community became increasingly unified as they thought and planned for their new house of worship. The nation at large, however, was becoming increasingly fractured. In December of 1860, South Carolina was the first of the Southern states to declare secession. Alabama was soon to follow. Montgomery became the first capital of the newly formed Confederacy, and Jefferson Davis’ inauguration took place on the steps of its capitol building. War was imminent. As the members of Kahl Montgomery celebrated their ninth anniversary on April 12, 1861, hundreds of miles away Confederate troops fired the first shots of the Civil War.

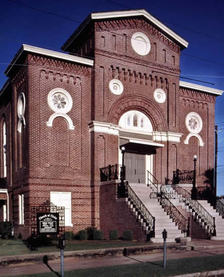

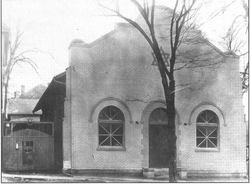

On March 8, 1862 the members of congregation Kahl Montgomery gathered to celebrate the dedication of their newly completed home. Rabbi James K. Gutheim, visiting from New Orleans, led services and delivered a sermon. In a radical departure from their Orthodox tradition, the dedication services included a choir and portions of English reading. Described as a “perfect example of Italian Romanesque architecture” by the Daily Advertiser, the building loomed above its congregants with its intricate brickwork, round windows, and impressive balustrades. As the Jews of Montgomery looked gratefully at their new house of worship, the world experienced its first ironclad battle off the coast of Virginia, and the nation sunk deep into the realities of a grim and sustained civil war.

Confederate Capital & Montgomery Jews

During the war, Montgomery did not face the same level of large-scale destruction that many Southern cities endured. The Confederate capital moved to Richmond, so Montgomery was spared from much of the Union’s attacks. Its citizens did, however, face the hardships of food shortage and lacking basic supplies for living. Many Jewish businessmen suffered under these challenging economic conditions. However, due to the high cost of goods, many dry goods merchants prospered through the war.

Many Montgomery Jews also worked within the ranks of the Confederacy. Judah P. Benjamin, a senator from Louisiana before the war and cabinet official in the Confederate government, spent some time in Montgomery during the war. Meyer Lehman was sent to Europe on a secret Confederate mission to sells bonds. Jacob Kohn, the shoemaker from Bavaria, became superintendent of the Confederacy’s shoe factory in Montgomery. When the war was over, Kohn took over the factory completely, and it became one of the largest factories in the South during the Reconstruction era. After the Union army captured New Orleans, Rabbi Gutheim, who had been fondly received during their dedication service, was unwilling to pledge allegiance to the Union. In June of 1863, he moved to Montgomery and became the first full time rabbi of Kahl Montgomery.

After the Civil War

Many members of Kahl Montgomery emerged from the war and achieved a great deal of success. The Lehman Brothers, whose cotton exchange firm had won them a fortune prior to the war, entered Reconstruction on the brink of controlling one of the most successful investment banks in the country. Prior to the war, Emanuel traveled to New York to open up an office of their firm on Wall Street. After the war, they closed their Montgomery office, and relocated the entire business to New York, where they helped establish the Cotton Exchange. With increasing investments in the railroad industry, Lehman Brothers Incorporated soon extended its operations to include the buying and selling of securities and rose to be one of the top financial institutions in the country. From its roots as a Montgomery-based cotton trading company, Lehman Brothers Holdings Incorporated went on to become a diversified global finance firm. The Lehmans were not alone in enjoying the transition from Old South to New South. As the nation struggled over Reconstruction, many Jews in Montgomery ascended the economic and political strata of the recently reunited states of America.

With twelve families in all, the Jews of Montgomery organized Congregation Kahl Montgomery on May 6, 1849. At first they worshiped in congregants' homes, organizing lay-led, Orthodox services, but as their numbers expanded they began to rent out Lyceum Hall on Dexter Avenue. Jews from neighboring towns came to Montgomery weekly to participate in services. Gentiles, never having seen Jews or their religious practices before, came to watch the ceremonies with an awed curiosity.

Kahl Montgomery drafted an official charter in 1852, and they continued to practice in rented space, without the resources to buy their own building. However, when wealthy New Orleans philanthropist Judah Touro died in 1858, he left money for Jewish congregations around the country, including Kahl Montgomery, which received $2,000 to build a synagogue. With this exciting development, Josiah Weil became Kahl Montgomery’s first president and established a committee to plan for the construction of a new building. In 1859, the group voted to purchase a plot on the corner of Church and Catoma Street.

The Jewish community became increasingly unified as they thought and planned for their new house of worship. The nation at large, however, was becoming increasingly fractured. In December of 1860, South Carolina was the first of the Southern states to declare secession. Alabama was soon to follow. Montgomery became the first capital of the newly formed Confederacy, and Jefferson Davis’ inauguration took place on the steps of its capitol building. War was imminent. As the members of Kahl Montgomery celebrated their ninth anniversary on April 12, 1861, hundreds of miles away Confederate troops fired the first shots of the Civil War.

On March 8, 1862 the members of congregation Kahl Montgomery gathered to celebrate the dedication of their newly completed home. Rabbi James K. Gutheim, visiting from New Orleans, led services and delivered a sermon. In a radical departure from their Orthodox tradition, the dedication services included a choir and portions of English reading. Described as a “perfect example of Italian Romanesque architecture” by the Daily Advertiser, the building loomed above its congregants with its intricate brickwork, round windows, and impressive balustrades. As the Jews of Montgomery looked gratefully at their new house of worship, the world experienced its first ironclad battle off the coast of Virginia, and the nation sunk deep into the realities of a grim and sustained civil war.

Confederate Capital & Montgomery Jews

During the war, Montgomery did not face the same level of large-scale destruction that many Southern cities endured. The Confederate capital moved to Richmond, so Montgomery was spared from much of the Union’s attacks. Its citizens did, however, face the hardships of food shortage and lacking basic supplies for living. Many Jewish businessmen suffered under these challenging economic conditions. However, due to the high cost of goods, many dry goods merchants prospered through the war.

Many Montgomery Jews also worked within the ranks of the Confederacy. Judah P. Benjamin, a senator from Louisiana before the war and cabinet official in the Confederate government, spent some time in Montgomery during the war. Meyer Lehman was sent to Europe on a secret Confederate mission to sells bonds. Jacob Kohn, the shoemaker from Bavaria, became superintendent of the Confederacy’s shoe factory in Montgomery. When the war was over, Kohn took over the factory completely, and it became one of the largest factories in the South during the Reconstruction era. After the Union army captured New Orleans, Rabbi Gutheim, who had been fondly received during their dedication service, was unwilling to pledge allegiance to the Union. In June of 1863, he moved to Montgomery and became the first full time rabbi of Kahl Montgomery.

After the Civil War

Many members of Kahl Montgomery emerged from the war and achieved a great deal of success. The Lehman Brothers, whose cotton exchange firm had won them a fortune prior to the war, entered Reconstruction on the brink of controlling one of the most successful investment banks in the country. Prior to the war, Emanuel traveled to New York to open up an office of their firm on Wall Street. After the war, they closed their Montgomery office, and relocated the entire business to New York, where they helped establish the Cotton Exchange. With increasing investments in the railroad industry, Lehman Brothers Incorporated soon extended its operations to include the buying and selling of securities and rose to be one of the top financial institutions in the country. From its roots as a Montgomery-based cotton trading company, Lehman Brothers Holdings Incorporated went on to become a diversified global finance firm. The Lehmans were not alone in enjoying the transition from Old South to New South. As the nation struggled over Reconstruction, many Jews in Montgomery ascended the economic and political strata of the recently reunited states of America.

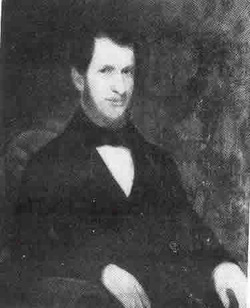

The Moses Brothers of Montgomery

Among the most prominent Jews in Montgomery following the war was Mordecai Moses, who rose through the ranks of local political alliances and became Montgomery’s first Democratic Mayor following Republican-ruled Reconstruction. Moses’ brother Alfred came to Montgomery from Charleston, South Carolina, as a young man to clerk at a law firm. He may have been the first Jewish professional in the city. Mordecai soon followed. Both served in the Confederacy, and following the war began a real estate and insurance company called Moses Brothers. Together with other members of Kahl Montgomery like the Weils, the Griels, and the Lehmans, the Moses brothers made up a new Jewish aristocracy in the city, those with the sufficient wealth and property to interact with the Gentiles in power. With his ties to the larger community and his renowned winning smile, Mordecai achieved the title of alderman in 1871, and from this position was elected mayor in 1875.

Mordecai Moses’ rise to power and his subsequent tenure as mayor were not without anti-Semitic challenges to his character. If it had not been for his friendship with editor of the Montgomery Advertiser, William Wallace Screws, he might not have been able to withstand the assaults. During the 1875 campaign, Screws diligently portrayed Moses’ opponent—the incumbent H.E. Faber—as a “bumbling, anti-Semitic, Reconstructionist.” According to the Advertiser, Republican Faber was beholden to the black vote and Democratic Moses was the “true white man’s candidate.” In 1879, when Moses was up for reelection for his second term, many critics cited his Judaism as an impetus for electing a new mayor. Screws published an editorial entitled “He’s a Jew,” which defended Moses’ Judaism: “Moses the wisest of law, was a Jew… David, a man after God’s heart, was a Jew… Jesus Christ himself was a Jew… It is too late in the history of the world for any illiberality to prevail as that a man does not deserve public confidence because he is a Jew.” Moses won reelection that year.

When Moses entered office, Montgomery was in debt and had little money in its public treasury. With the arrival of six new railroads and the continued navigational developments of the Alabama River, Montgomery experienced a tremendous boom in the 1870s and 1880s. Moses brought ample funds into the city government and paid off all floating debts. He also led the campaign to bring electricity to Montgomery with new electric street cars and street lights. After leaving the mayor’s office, Moses reunited with his brother in several new business ventures. They built a six story office building by Court Square, which was the largest in the city for years. Together the Moses brothers led successful projects in suburban development, and even founded a new town.

One day, while Alfred Moses stopped to inspect some cotton fields near the banks of the Tennessee River, he became overwhelmed with the potential that the peaceful spot had as an industrial hub. With this vision for real estate and industry, Mordecai and Alfred founded the Sheffield Land, Iron, and Coal Company and soon the town of Sheffield was born. Alfred became mayor in 1886. He oversaw the construction of the public school, all the municipal buildings, and the installation of the first iron furnace. He watched as industrial workers and their families moved into small settlements.

With its company town growing, and the chimneys of its factories billowing, the Sheffield Land, Iron, and Coal Company achieved a net worth of $4.5 million in 1888. However, by the end of the year, when a large investment company went bankrupt, it was a huge blow to many Southern businesses, the Sheffield Company included. In 1889, the furnace at Sheffield closed, and the town went mostly defunct. The Moses brothers lost hundreds of thousands of dollars, and, when the Panic of 1893 hit, they were financially ruined. The whole family moved to St. Louis where the brothers lived in their sisters’ boarding house and ran a modest real estate firm.

Among the most prominent Jews in Montgomery following the war was Mordecai Moses, who rose through the ranks of local political alliances and became Montgomery’s first Democratic Mayor following Republican-ruled Reconstruction. Moses’ brother Alfred came to Montgomery from Charleston, South Carolina, as a young man to clerk at a law firm. He may have been the first Jewish professional in the city. Mordecai soon followed. Both served in the Confederacy, and following the war began a real estate and insurance company called Moses Brothers. Together with other members of Kahl Montgomery like the Weils, the Griels, and the Lehmans, the Moses brothers made up a new Jewish aristocracy in the city, those with the sufficient wealth and property to interact with the Gentiles in power. With his ties to the larger community and his renowned winning smile, Mordecai achieved the title of alderman in 1871, and from this position was elected mayor in 1875.

Mordecai Moses’ rise to power and his subsequent tenure as mayor were not without anti-Semitic challenges to his character. If it had not been for his friendship with editor of the Montgomery Advertiser, William Wallace Screws, he might not have been able to withstand the assaults. During the 1875 campaign, Screws diligently portrayed Moses’ opponent—the incumbent H.E. Faber—as a “bumbling, anti-Semitic, Reconstructionist.” According to the Advertiser, Republican Faber was beholden to the black vote and Democratic Moses was the “true white man’s candidate.” In 1879, when Moses was up for reelection for his second term, many critics cited his Judaism as an impetus for electing a new mayor. Screws published an editorial entitled “He’s a Jew,” which defended Moses’ Judaism: “Moses the wisest of law, was a Jew… David, a man after God’s heart, was a Jew… Jesus Christ himself was a Jew… It is too late in the history of the world for any illiberality to prevail as that a man does not deserve public confidence because he is a Jew.” Moses won reelection that year.

When Moses entered office, Montgomery was in debt and had little money in its public treasury. With the arrival of six new railroads and the continued navigational developments of the Alabama River, Montgomery experienced a tremendous boom in the 1870s and 1880s. Moses brought ample funds into the city government and paid off all floating debts. He also led the campaign to bring electricity to Montgomery with new electric street cars and street lights. After leaving the mayor’s office, Moses reunited with his brother in several new business ventures. They built a six story office building by Court Square, which was the largest in the city for years. Together the Moses brothers led successful projects in suburban development, and even founded a new town.

One day, while Alfred Moses stopped to inspect some cotton fields near the banks of the Tennessee River, he became overwhelmed with the potential that the peaceful spot had as an industrial hub. With this vision for real estate and industry, Mordecai and Alfred founded the Sheffield Land, Iron, and Coal Company and soon the town of Sheffield was born. Alfred became mayor in 1886. He oversaw the construction of the public school, all the municipal buildings, and the installation of the first iron furnace. He watched as industrial workers and their families moved into small settlements.

With its company town growing, and the chimneys of its factories billowing, the Sheffield Land, Iron, and Coal Company achieved a net worth of $4.5 million in 1888. However, by the end of the year, when a large investment company went bankrupt, it was a huge blow to many Southern businesses, the Sheffield Company included. In 1889, the furnace at Sheffield closed, and the town went mostly defunct. The Moses brothers lost hundreds of thousands of dollars, and, when the Panic of 1893 hit, they were financially ruined. The whole family moved to St. Louis where the brothers lived in their sisters’ boarding house and ran a modest real estate firm.

Embracing Religious Reform

Reconstruction also proved to be a flourishing time for Kahl Montgomery as the congregation began to grow with the arrival of new immigrant groups from Eastern Europe. In 1871, affluent members of the community donated their money to establish the Standard Club, a social club for Jews. Located across the street from the popular Davis Theater, the Standard Club stood as a lively symbol of the Jewish community’s prominence in Montgomery.

Besides enjoying growth and prosperity, Kahl Montgomery underwent a great deal of transformation following the war. The community had shifted farther and farther away from its Orthodox origins and had adopted various Reform rituals. Many feared that by sticking to stricter traditions, the congregation would suffer from lower attendance by business people who could not conform to the strictures of an Orthodox lifestyle. In 1873, the congregation decided to amend its constitution to reflect these changes in practice. These changes caused much debate among congregants over such issues as head coverings and the seating location of women and children during services. They decided that head coverings could be optional, and that women should sit with men in services. To reflect this change in ritual, the congregation decided it must also change its name. In 1874, Congregation Kahl Montgomery became Temple Beth Or (House of Light).

More changes and progress occurred as Beth Or moved towards the twentieth century. By 1873, they had instituted the Reform confirmation ritual. In 1876, Rabbi Sigmund Hecht became their first rabbi to serve for over a year, leading the congregation for twelve years. In 1879, they joined the Union of America Hebrew Congregations, the official body of the Reform movement. At about this time, Beth Or also founded a Sunday school. Though there were only seventy members in the congregation, their new Sunday school had 112 children enrolled. Given the growing number of children in their religious school, by the end of the nineteenth century, Beth Or began planning construction of a new, larger synagogue. Montgomery Jews also established The Falcon Club in 1899, a "literary and social" organization for young people that became well known for its annual, weekend-long courtship event, as well as dances and lectures. Despite these developments, a segment of newly arrived Montgomery Jews soon sought a new home, outside of the bounds of Beth Or.

Reconstruction also proved to be a flourishing time for Kahl Montgomery as the congregation began to grow with the arrival of new immigrant groups from Eastern Europe. In 1871, affluent members of the community donated their money to establish the Standard Club, a social club for Jews. Located across the street from the popular Davis Theater, the Standard Club stood as a lively symbol of the Jewish community’s prominence in Montgomery.

Besides enjoying growth and prosperity, Kahl Montgomery underwent a great deal of transformation following the war. The community had shifted farther and farther away from its Orthodox origins and had adopted various Reform rituals. Many feared that by sticking to stricter traditions, the congregation would suffer from lower attendance by business people who could not conform to the strictures of an Orthodox lifestyle. In 1873, the congregation decided to amend its constitution to reflect these changes in practice. These changes caused much debate among congregants over such issues as head coverings and the seating location of women and children during services. They decided that head coverings could be optional, and that women should sit with men in services. To reflect this change in ritual, the congregation decided it must also change its name. In 1874, Congregation Kahl Montgomery became Temple Beth Or (House of Light).

More changes and progress occurred as Beth Or moved towards the twentieth century. By 1873, they had instituted the Reform confirmation ritual. In 1876, Rabbi Sigmund Hecht became their first rabbi to serve for over a year, leading the congregation for twelve years. In 1879, they joined the Union of America Hebrew Congregations, the official body of the Reform movement. At about this time, Beth Or also founded a Sunday school. Though there were only seventy members in the congregation, their new Sunday school had 112 children enrolled. Given the growing number of children in their religious school, by the end of the nineteenth century, Beth Or began planning construction of a new, larger synagogue. Montgomery Jews also established The Falcon Club in 1899, a "literary and social" organization for young people that became well known for its annual, weekend-long courtship event, as well as dances and lectures. Despite these developments, a segment of newly arrived Montgomery Jews soon sought a new home, outside of the bounds of Beth Or.

A New Brotherhood, A New Century

In 1900, Beth Or was in the middle of negotiating a deal with a church group to sell their original building. Though there was some resistance to selling their former place of worship to another religious group, committee members came to a resolution and were successful at selling the building to what is now the Catoma Street Church, which still stands today. Beth Or members also began to finish plans for their new home. On January 1, 1901, Beth Or laid of the cornerstone of their new building on the corner of Sayre and Clayton Street and celebrated with a lively procession from their old building to the new one, carrying Torah scrolls and singing songs as they went. A young Lucien Loeb held an eternal light; fifty-nine years later his son would do the same at a similar procession. The mayor of Montgomery and a well known Baptist minister took part in the service, alongside congregational president David Weil. In the year that followed, Beth Or saw the completion of its new building.

That same year, sixteen members of Beth Or announced that they were embarking on a new chapter of Montgomery Jewish history. The growing number of immigrants from Eastern Europe had attended services regularly and spent hours praying in Beth Or’s sanctuary. Longing for Hebrew-language services and Orthodox ritual, these members of Beth Or decided it was time for Montgomery to have a second Jewish congregation. The breakaway group called themselves Congregation Agudath Israel (Brothers of Israel). Agudath Israel’s first president, Max Shulwolf, originally from Hungary by way of Galveston, Texas, ran a small dry goods store with M.S. Katz. Shulwolf and his wife donated two rooms of their house to function as an open worship place for the members of the new congregation. It was there that Agudath Israel drafted its first constitution, written in Yiddish. During their services, men sat separately from women, wore head coverings, and prayed in Yiddish and Hebrew.

In the following years, Agudath Israel grew and had to move from place to place for High Holiday services. They prayed in such diverse locations as a rented office space above the National Shirt Company on Court Square and an annex of the First National Bank. Many Orthodox Jews flocked to Montgomery to join Agudath Israel, excited to practice the customs of their former homelands once again. In 1914, Montgomery enjoyed yet another Jewish dedication ceremony when Agudath Israel moved into their first permanent synagogue on Monroe Street.

The Road from Rhodes: Sephardim in Montgomery

On the other side of the world, on the small Aegean island of Rhodes, in a neighborhood called Juderia, a tight-knit group of Jewish families began to hear good things about Montgomery, Alabama. These Sephardic Jews left Spain during the Inquisition and came to Rhodes where they established a lively Jewish community. At one point there were six synagogues on the small island. Their main synagogue, Kahal Shalom, was the oldest in all of Greece. Having been under the authority of various empires and states, the island had a wide mix of cultures—walking outside one could hear French, Turkish, Italian Greek, Hebrew, and Ladino. However, by the beginning of the 20th century, many young Jews had few economic opportunities, given the small size of Rhodes. Morris Capouya, who immigrated to the United States in 1927, explained that he chose to leave Rhodes because there was “no future on the island for young men.” When their Greek Orthodox neighbors returned to the island after having been to the United States, with stories of booming American cities, hopeful young Jews took note.

In the summer of 1906, Ralph Nace Cohen embarked from the Isle of Patmos on a small frigate crossing the Aegean Sea. From there, he likely boarded another ship, which crossed the Mediterranean, and then another for the long trip across the Atlantic. He then made his way to Montgomery, probably by train, where he became the first Sephardic Jew in the city. Capouya recalled a local story that upon arriving in New York, a group of Sephardic immigrants went to the train station, presented all the money they had at the ticket counter, and asked to go as far south as their money could take them. They ended up in Montgomery. Without knowing anyone, and with little ability to speak English, Cohen opened a hat shop. News of Cohen’s safe and prosperous landing in Montgomery must have reached Rhodes, because within that year 11 other young Jews from Rhodes found their way to Montgomery. As more Sephardic Jews came to Montgomery, its reputation as a thriving community bounced from coast to coast of the Aegean Sea. Montgomery became home to Sephardic Jews from all over Turkey and Greece. Around the same time, Sephardic Jews from the Ottoman Empire and the Balkans were immigrating to and building Sephardic communities throughout the Americas from Florida, to southern California, to Buenos Aires.

In 1908, the Sephardic immigrants who settled in Montgomery gathered at the Orthodox Community Center, a rented space established by Agudath Israel, to celebrate their first Sephardic High Holidays services. Although Sephardic Jews also came from Salonica, Turkey, and elsewhere in the Balkans and Ottoman Empire, the majority had immigrated from Rhodes; as a result, Rhodian minhagim became the established norm.

In 1900, Beth Or was in the middle of negotiating a deal with a church group to sell their original building. Though there was some resistance to selling their former place of worship to another religious group, committee members came to a resolution and were successful at selling the building to what is now the Catoma Street Church, which still stands today. Beth Or members also began to finish plans for their new home. On January 1, 1901, Beth Or laid of the cornerstone of their new building on the corner of Sayre and Clayton Street and celebrated with a lively procession from their old building to the new one, carrying Torah scrolls and singing songs as they went. A young Lucien Loeb held an eternal light; fifty-nine years later his son would do the same at a similar procession. The mayor of Montgomery and a well known Baptist minister took part in the service, alongside congregational president David Weil. In the year that followed, Beth Or saw the completion of its new building.

That same year, sixteen members of Beth Or announced that they were embarking on a new chapter of Montgomery Jewish history. The growing number of immigrants from Eastern Europe had attended services regularly and spent hours praying in Beth Or’s sanctuary. Longing for Hebrew-language services and Orthodox ritual, these members of Beth Or decided it was time for Montgomery to have a second Jewish congregation. The breakaway group called themselves Congregation Agudath Israel (Brothers of Israel). Agudath Israel’s first president, Max Shulwolf, originally from Hungary by way of Galveston, Texas, ran a small dry goods store with M.S. Katz. Shulwolf and his wife donated two rooms of their house to function as an open worship place for the members of the new congregation. It was there that Agudath Israel drafted its first constitution, written in Yiddish. During their services, men sat separately from women, wore head coverings, and prayed in Yiddish and Hebrew.

In the following years, Agudath Israel grew and had to move from place to place for High Holiday services. They prayed in such diverse locations as a rented office space above the National Shirt Company on Court Square and an annex of the First National Bank. Many Orthodox Jews flocked to Montgomery to join Agudath Israel, excited to practice the customs of their former homelands once again. In 1914, Montgomery enjoyed yet another Jewish dedication ceremony when Agudath Israel moved into their first permanent synagogue on Monroe Street.

The Road from Rhodes: Sephardim in Montgomery

On the other side of the world, on the small Aegean island of Rhodes, in a neighborhood called Juderia, a tight-knit group of Jewish families began to hear good things about Montgomery, Alabama. These Sephardic Jews left Spain during the Inquisition and came to Rhodes where they established a lively Jewish community. At one point there were six synagogues on the small island. Their main synagogue, Kahal Shalom, was the oldest in all of Greece. Having been under the authority of various empires and states, the island had a wide mix of cultures—walking outside one could hear French, Turkish, Italian Greek, Hebrew, and Ladino. However, by the beginning of the 20th century, many young Jews had few economic opportunities, given the small size of Rhodes. Morris Capouya, who immigrated to the United States in 1927, explained that he chose to leave Rhodes because there was “no future on the island for young men.” When their Greek Orthodox neighbors returned to the island after having been to the United States, with stories of booming American cities, hopeful young Jews took note.

In the summer of 1906, Ralph Nace Cohen embarked from the Isle of Patmos on a small frigate crossing the Aegean Sea. From there, he likely boarded another ship, which crossed the Mediterranean, and then another for the long trip across the Atlantic. He then made his way to Montgomery, probably by train, where he became the first Sephardic Jew in the city. Capouya recalled a local story that upon arriving in New York, a group of Sephardic immigrants went to the train station, presented all the money they had at the ticket counter, and asked to go as far south as their money could take them. They ended up in Montgomery. Without knowing anyone, and with little ability to speak English, Cohen opened a hat shop. News of Cohen’s safe and prosperous landing in Montgomery must have reached Rhodes, because within that year 11 other young Jews from Rhodes found their way to Montgomery. As more Sephardic Jews came to Montgomery, its reputation as a thriving community bounced from coast to coast of the Aegean Sea. Montgomery became home to Sephardic Jews from all over Turkey and Greece. Around the same time, Sephardic Jews from the Ottoman Empire and the Balkans were immigrating to and building Sephardic communities throughout the Americas from Florida, to southern California, to Buenos Aires.

In 1908, the Sephardic immigrants who settled in Montgomery gathered at the Orthodox Community Center, a rented space established by Agudath Israel, to celebrate their first Sephardic High Holidays services. Although Sephardic Jews also came from Salonica, Turkey, and elsewhere in the Balkans and Ottoman Empire, the majority had immigrated from Rhodes; as a result, Rhodian minhagim became the established norm.

|

In 1912, the small collection of Sephardic Jews came together and wrote a constitution in Ladino. They called themselves Congregation Etz Ahayem, Tree of Life, a traditional name in the Sephardic Jewish tradition. For the entirety of their existence, Etz Ahayem would try to preserve their customs, passing down traditional recipes and Ladino songs. These traditions, however, often raised skepticism among the Ashkenazi community. Some Ashkenazi Jews doubted the authenticity of Sephardim as they did not speak Yiddish, spoke Hebrew with a Sephardic accent, and conducted services differently. For example, Etz Ahayem observed the minhag of “selling” mitzvot, in which congregation members would bid against one another for various honors, such as Torah and Haftarah aliyot, the opening of the ark, and the carrying of the Torah. Sephardic foodways also differed from their Ashkenazi neighbors, as they were heavily influenced by Greek and Turkish traditions. Morris Capouya recalled eating rice at every lunch and supper, as well as meats, dolmades, and grape leaves.

|

Albert Capp (1922-2008) and Ralph Franco (1922-2003) grew up in Etz Ahayem. In this video, Capp and Franco describe the Sephardic minhagim (customs) practiced at Etz Ahayem synagogue in Montgomery, Alabama. They discuss the Sephardic pronunciation of prayers and the Sephardic practice of "selling" mitzvot to community members. |

Members of Beth Or, having lived in the city for generations, were more established financially and socially. The Sephardim of Etz Ahayem, mostly working class and newly immigrated, did not initially have the same level of prestige or power. Ralph Franco recalled that some social organizations, such as the Standard Club and non-Jewish social clubs, did not accept most Sephardim. Despite these discriminatory practices, he explained that any contention was primarily between individuals rather than between the communities as a whole. Other clubs, such as The Falcon, welcomed Sephardim at their events. Despite some tension, Temple Beth Or gave a Torah to Etz Ahayem in 1918, only six years after Etz Ahayem was established. Temple Beth Or also invited Sephardic children to attend their Sunday school, which facilitated interaction between the congregations. Over time, the communities became more integrated as intermarriage between Sephardim and Ashkenazim increased.

The Early 20th Century

The coming of World War I brought about a new period of Jewish participation in civic life. Young men from all three congregations served in the armed forces. The following decades were ones of intense challenges brought on Great Depression and yet another world war. The Jews of Montgomery, however, persevered and continued.

At the end of World War I, Beth Or’s new building was already in need of repairs. They embarked on many renovations of their temple, making it up to date for a new modern age. In 1926, Beth Or added a kitchen to their building. In 1927, they celebrated their 75 years as an organized congregation with a huge banquet at the Standard Club.

Agudath Israel also experienced a great deal of growth during this time period. In 1914, they moved into their own building on Monroe Street and hired their first full time rabbi. With a rabbi and new building, the members of Agudath contentedly worshiped for several years, until the state of Alabama bought the property for public use in 1927. By this time Agudath Israel had grown to 65 families, so they looked forward to moving to a larger space. In April of 1927, construction began on newly purchased land on McDonough and High Street, and within months the building was ready for High Holiday services. With a huge and festive dedication ceremony, Agudath Israel moved homes with a stately procession of Torah scrolls.

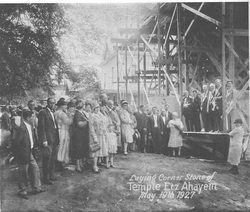

In 1916, Etz Ahayem was officially incorporated. Soon after, Montgomery’s newest congregation enjoyed rapid growth. By 1918 they had enough families and funding to buy a plot on Sayre Street for their synagogue, though construction would not be complete for years. Despite their recent arrival, the Sephardic community established important connections. U.S. Senator Joseph Lister Hill of Alabama proved to be a valuable aid in immigration issues for the Sephardic community for many years. Despite some tensions, Etz Ahayem was able to form bonds with the other two Jewish congregations of Montgomery. Beth Or donated a Torah scroll to Etz Ahayem at their founding and invited the Sephardic children to enroll in their religious school. With the implementation of strict new quotas in 1924, immigration from Rhodes effectively stopped, and Etz Ahayem’s growth slowed. In 1927, with 27 families gathered, Etz Ahayem paraded their Torah scrolls, sang proudly in Ladino, and stepped into the portals of a newly constructed synagogue as they celebrated its dedication.

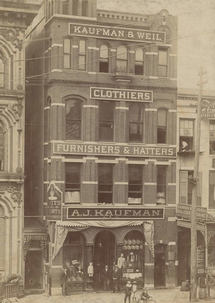

Despite the challenges posed by the economic downturn of the 1930s, many Jews in Montgomery continued to flourish. Jewish merchants and retailers filled The Five Points neighborhood of Montgomery. Their ranks included everything from small fruit cart operators to large department store owners. In the tradition of such pioneers as the Moses and Lehman brothers, the buildings of Jewish businessmen also occupied downtown Montgomery. Among the dozens of shops, there was Weil’s Department Store on Monroe Street, Cohen’s Amusement’s on Dexter Avenue, Klein and Sons Jewelers, and Kaufman and Weil Clothiers.

The coming of World War I brought about a new period of Jewish participation in civic life. Young men from all three congregations served in the armed forces. The following decades were ones of intense challenges brought on Great Depression and yet another world war. The Jews of Montgomery, however, persevered and continued.

At the end of World War I, Beth Or’s new building was already in need of repairs. They embarked on many renovations of their temple, making it up to date for a new modern age. In 1926, Beth Or added a kitchen to their building. In 1927, they celebrated their 75 years as an organized congregation with a huge banquet at the Standard Club.

Agudath Israel also experienced a great deal of growth during this time period. In 1914, they moved into their own building on Monroe Street and hired their first full time rabbi. With a rabbi and new building, the members of Agudath contentedly worshiped for several years, until the state of Alabama bought the property for public use in 1927. By this time Agudath Israel had grown to 65 families, so they looked forward to moving to a larger space. In April of 1927, construction began on newly purchased land on McDonough and High Street, and within months the building was ready for High Holiday services. With a huge and festive dedication ceremony, Agudath Israel moved homes with a stately procession of Torah scrolls.

In 1916, Etz Ahayem was officially incorporated. Soon after, Montgomery’s newest congregation enjoyed rapid growth. By 1918 they had enough families and funding to buy a plot on Sayre Street for their synagogue, though construction would not be complete for years. Despite their recent arrival, the Sephardic community established important connections. U.S. Senator Joseph Lister Hill of Alabama proved to be a valuable aid in immigration issues for the Sephardic community for many years. Despite some tensions, Etz Ahayem was able to form bonds with the other two Jewish congregations of Montgomery. Beth Or donated a Torah scroll to Etz Ahayem at their founding and invited the Sephardic children to enroll in their religious school. With the implementation of strict new quotas in 1924, immigration from Rhodes effectively stopped, and Etz Ahayem’s growth slowed. In 1927, with 27 families gathered, Etz Ahayem paraded their Torah scrolls, sang proudly in Ladino, and stepped into the portals of a newly constructed synagogue as they celebrated its dedication.

Despite the challenges posed by the economic downturn of the 1930s, many Jews in Montgomery continued to flourish. Jewish merchants and retailers filled The Five Points neighborhood of Montgomery. Their ranks included everything from small fruit cart operators to large department store owners. In the tradition of such pioneers as the Moses and Lehman brothers, the buildings of Jewish businessmen also occupied downtown Montgomery. Among the dozens of shops, there was Weil’s Department Store on Monroe Street, Cohen’s Amusement’s on Dexter Avenue, Klein and Sons Jewelers, and Kaufman and Weil Clothiers.

Rubin Hanan

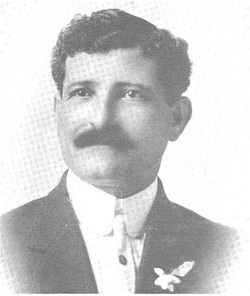

Rubin Hanan of Etz Ahayem represented the versatility and tenacity of the Montgomery Jewish community. For the Montgomery Sephardic community he acted as legal consultant, marriage counselor, historian, and poet laureate. He came to the U.S. from Rhodes in 1925 at 17 years old after an eventful journey. Having difficulty obtaining a student visa, Hanan stayed in Naples, Italy for a while, where by chance he met with Prime Minister Benito Mussolini. Somehow, Hanan charmed the Italian fascist leader, and Mussolini issued him false identification, which proved to be enough to get the Rhodian youth on a boat to Ellis Island. Once there, Hanan received help from Senator Lister Hill. Unable to speak English, Hanan had a note around his neck asking to be delivered to the address of his relatives, the Franco family in Montgomery.

Hanan quickly learned English, and received training in pharmacy, accounting, and law. Professionally, Hanan worked on the staff of three Alabama Governors: James Folsom, John Patterson, and George Wallace. Late in his career, Hanan became a major advocate for the rights of the aging. In 1965, President Lyndon Johnson appointed Hanan to the Advisory Committee for Older Americans. Hanan contributed huge sums of money to the Lister Hill Medical Center, and has a wing named after him there. In 1988, he was officially commended by the Alabama Senate for “his outstanding achievement and service to community, state, and nation.”

Rubin Hanan of Etz Ahayem represented the versatility and tenacity of the Montgomery Jewish community. For the Montgomery Sephardic community he acted as legal consultant, marriage counselor, historian, and poet laureate. He came to the U.S. from Rhodes in 1925 at 17 years old after an eventful journey. Having difficulty obtaining a student visa, Hanan stayed in Naples, Italy for a while, where by chance he met with Prime Minister Benito Mussolini. Somehow, Hanan charmed the Italian fascist leader, and Mussolini issued him false identification, which proved to be enough to get the Rhodian youth on a boat to Ellis Island. Once there, Hanan received help from Senator Lister Hill. Unable to speak English, Hanan had a note around his neck asking to be delivered to the address of his relatives, the Franco family in Montgomery.

Hanan quickly learned English, and received training in pharmacy, accounting, and law. Professionally, Hanan worked on the staff of three Alabama Governors: James Folsom, John Patterson, and George Wallace. Late in his career, Hanan became a major advocate for the rights of the aging. In 1965, President Lyndon Johnson appointed Hanan to the Advisory Committee for Older Americans. Hanan contributed huge sums of money to the Lister Hill Medical Center, and has a wing named after him there. In 1988, he was officially commended by the Alabama Senate for “his outstanding achievement and service to community, state, and nation.”

World War II

With the coming of yet another world war, the Jewish community sincerely felt the weight of world events. Members of all three congregations served abroad. Over one hundred men and women from Beth Or served in the U.S. armed forces. The Jewish community of Montgomery actively hosted and welcomed the Jewish troops stationed at nearby Maxwell Air Force Base.

The terror of the Holocaust brought a crushing blow to all American Jews, Montgomery included. For Etz Ahayem, with so many familial links to Axis-dominated Rhodes, the war brought horrible tragedies. When the Germans took over Rhodes in 1943, of the 2,000 Sephardim living there, the Nazi troops captured and transported 1,673 to Auschwitz. Nearly every member of Etz Ahayem had a close family member who died in the Holocaust. Before the Germans occupied Rhodes however, the congregation of Kal Grande buried their Torah scrolls. After the war, they were recovered and sent to Israel. By the arrangement of Dr. Nace Cohen, one of these scrolls became Etz Ahayem’s second Torah, creating a strong symbolic connection to their wounded place of origin.

The Mid-20th Century

Reeling from the devastating reports of the war and its aftermath, the Jewish community of Montgomery entered the 1950s, an era of prosperity and rapid change, with a steady perseverance. Both Etz Ahayem and Agudath Israel made important changes to their constitutions and religious practices. Etz Ahayem went from praying strictly in Ladino and Hebrew to a service that included a great deal of English. Agudath Israel, aware of the shifting practices of their congregants, moved away from strict Orthodoxy to embrace Conservative Judaism. All three congregations made plans to move synagogues to reflect the changing needs of their members. In 1957, Agudath Israel had a processional of their Torahs from their old building on Monroe Street to their new one on Cloverdale. In 1960, Beth Or moved from its longtime home on Clayton Street to a brand new facility on Narrow Lane Road. Etz Ahayem too, in a lively procession and celebration, moved to a new building in 1962.

Despite these major changes of location and practice, the individual histories of these congregations and the general history of the Jewish community are inextricably linked to that of the city of Montgomery. Though they may at times have wanted to look away or deny its existence, the 1950s were a time of comprehensive and tense social change, and Montgomery was an undeniable locus of heated activity and protest.

Montgomery Jews & Civil Rights

In the summer of 1955, a pamphlet called the “Jewish Perspective on Segregation” circulated all around Montgomery. Printed by the White Citizens’ Council, and supposedly written by a former member of B’nai B’rith, the pamphlet essentially argued that Jews believed segregation of blacks and whites was crucial for the well being of American society. This pamphlet likely was in response to the wave of anti-Semitic sentiment that arose after the landmark desegregation case Brown vs. the Topeka Board of Education. Immediately following the decision, the national Anti-Defamation League (founded originally by B’nai B’rith) declared their support for the Supreme Court ruling that race-based segregation was unjust and unconstitutional. Perhaps prompted by this declaration, many staunch segregationists publicly associated Brown with “Jewish and communist conspiracies.” This growing sentiment in the South invoked fear in many Southern Jews as they faced the challenges of dealing with the growing demands for civil rights and the often violent resistance to change. Given the choice between speaking out and remaining silent, most chose the latter.

Montgomery Jews had to wrestle with these issues even before 1955. Rabbi Benjamin Goldstein came to serve Beth Or from New York in 1928. Before being hired, the search committee informed him that for fear of an anti-Semitic backlash he “was not to address the Negro question.” However, in 1931, when nine young African American men were indicted for the rape of two white women based on faulty evidence, Goldstein could not remain silent. He was the only white clergyman to visit the so-called Scottsboro Boys in prison and was instrumental in connecting them to a team of lawyers from International Labor Defense, the legal arm of the American Communist Party, for the appeal trial. Upon seeing the northern Jewish lawyers, the prosecuting attorney exclaimed: “Alabama justice cannot be bought and sold with Jew money from New York.” On Yom Kippur in 1932, Goldstein defied intimidation and defended the Scottsboro boys in his sermon.

With the coming of yet another world war, the Jewish community sincerely felt the weight of world events. Members of all three congregations served abroad. Over one hundred men and women from Beth Or served in the U.S. armed forces. The Jewish community of Montgomery actively hosted and welcomed the Jewish troops stationed at nearby Maxwell Air Force Base.

The terror of the Holocaust brought a crushing blow to all American Jews, Montgomery included. For Etz Ahayem, with so many familial links to Axis-dominated Rhodes, the war brought horrible tragedies. When the Germans took over Rhodes in 1943, of the 2,000 Sephardim living there, the Nazi troops captured and transported 1,673 to Auschwitz. Nearly every member of Etz Ahayem had a close family member who died in the Holocaust. Before the Germans occupied Rhodes however, the congregation of Kal Grande buried their Torah scrolls. After the war, they were recovered and sent to Israel. By the arrangement of Dr. Nace Cohen, one of these scrolls became Etz Ahayem’s second Torah, creating a strong symbolic connection to their wounded place of origin.

The Mid-20th Century

Reeling from the devastating reports of the war and its aftermath, the Jewish community of Montgomery entered the 1950s, an era of prosperity and rapid change, with a steady perseverance. Both Etz Ahayem and Agudath Israel made important changes to their constitutions and religious practices. Etz Ahayem went from praying strictly in Ladino and Hebrew to a service that included a great deal of English. Agudath Israel, aware of the shifting practices of their congregants, moved away from strict Orthodoxy to embrace Conservative Judaism. All three congregations made plans to move synagogues to reflect the changing needs of their members. In 1957, Agudath Israel had a processional of their Torahs from their old building on Monroe Street to their new one on Cloverdale. In 1960, Beth Or moved from its longtime home on Clayton Street to a brand new facility on Narrow Lane Road. Etz Ahayem too, in a lively procession and celebration, moved to a new building in 1962.

Despite these major changes of location and practice, the individual histories of these congregations and the general history of the Jewish community are inextricably linked to that of the city of Montgomery. Though they may at times have wanted to look away or deny its existence, the 1950s were a time of comprehensive and tense social change, and Montgomery was an undeniable locus of heated activity and protest.

Montgomery Jews & Civil Rights

In the summer of 1955, a pamphlet called the “Jewish Perspective on Segregation” circulated all around Montgomery. Printed by the White Citizens’ Council, and supposedly written by a former member of B’nai B’rith, the pamphlet essentially argued that Jews believed segregation of blacks and whites was crucial for the well being of American society. This pamphlet likely was in response to the wave of anti-Semitic sentiment that arose after the landmark desegregation case Brown vs. the Topeka Board of Education. Immediately following the decision, the national Anti-Defamation League (founded originally by B’nai B’rith) declared their support for the Supreme Court ruling that race-based segregation was unjust and unconstitutional. Perhaps prompted by this declaration, many staunch segregationists publicly associated Brown with “Jewish and communist conspiracies.” This growing sentiment in the South invoked fear in many Southern Jews as they faced the challenges of dealing with the growing demands for civil rights and the often violent resistance to change. Given the choice between speaking out and remaining silent, most chose the latter.

Montgomery Jews had to wrestle with these issues even before 1955. Rabbi Benjamin Goldstein came to serve Beth Or from New York in 1928. Before being hired, the search committee informed him that for fear of an anti-Semitic backlash he “was not to address the Negro question.” However, in 1931, when nine young African American men were indicted for the rape of two white women based on faulty evidence, Goldstein could not remain silent. He was the only white clergyman to visit the so-called Scottsboro Boys in prison and was instrumental in connecting them to a team of lawyers from International Labor Defense, the legal arm of the American Communist Party, for the appeal trial. Upon seeing the northern Jewish lawyers, the prosecuting attorney exclaimed: “Alabama justice cannot be bought and sold with Jew money from New York.” On Yom Kippur in 1932, Goldstein defied intimidation and defended the Scottsboro boys in his sermon.

Words like those spoken by the prosecuting attorney and Goldstein’s persistence deeply troubled Beth Or’s board of trustees. Montgomery Mayor W. A. Gunter informed board members that if Goldstein did any more to assist in the Scottsboro trials, the Ku Klux Klan would organize a boycott of Jewish businesses in the city. Without permission, Rabbi Goldstein spoke publicly at a rally for the Scottsboro Boys. In April of 1933, Beth Or’s president Ernest Mayer informed Goldstein that he either had to quit his political activities or leave. Though two board members defended Goldstein, he presented his letter of resignation to the board the following day. Some confessed anonymously to the Montgomery Advertiser that they secretly sided with Goldstein. Nevertheless, Beth Or’s board published a press release declaring the congregation’s commitment to segregation. After leaving Montgomery for New York, Goldstein attempted to continue his career as a rabbi, but was unable to find work due to his activism and connection to communists.

Twenty years after Goldstein’s public dissent, the eyes of the country turned to Montgomery for what was a seminal episode in the struggle for civil rights. In December of 1955, with Rosa Parks initiating the first act of protest, the African American community began its year-long bus boycott to demand desegregation of Montgomery’s transit system. As the boycott gained momentum, the city bus system began to lose money, the enrollment of White Citizen’s Councils swelled, and Montgomery Jews watched again from their uncomfortable position as a religious minority within the ruling racial majority.

At this point in Montgomery’s history, the Jewish population had almost completely joined the ranks of its most prominent citizens; important banks and institutions were owned and operated by Jews, and many were active members of the local chapters of the Kiwanis and Masons. Rubin Hanan worked on the staff of Governor Folsom. In fact, Hanan was so ensconced in the ruling power structure that even Admiral John Crommelin an ardent segregationist and outspoken anti-Semite, considered him a friend and colleague. However, Jews still faced exclusion on account of their religion when trying to enter the Montgomery Country Club. Thus, many in the Jewish community, who did not want to face further marginalization, avoided addressing the boycott in any form.

The Jewish spiritual leadership took stands on both sides of the issue. Eugene Blachschlager, the rabbi who had replaced Goldstein at Beth Or, had learned from the example of his predecessor and spoke very little publicly about the boycott. He assured the board of trustees that he had absolutely no connection to the protest or its leadership. He supported them when they sent an angry letter to the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, who had endorsed the boycott. Rabbi Solomon Acrish of Etz Ahayem spoke publically in favor of the movement, citing the demand in the Torah for social justice. Acrish did not continue speaking against segregationist for long, however, as the environment became increasingly hostile. One day he noticed someone following him down the street. A Gentile family, with whom he had long been friends, told him he could not come to their home for dinner anymore because they had been told that Jews supported the boycott. Finally, after Etz Ahayem received a bomb threat by anonymous phone call, Acrish toned down his support of desegregation.

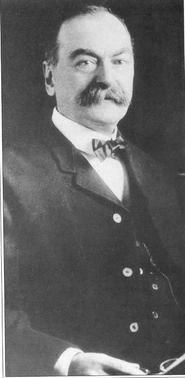

Rabbi Seymour Atlas of Agudath Israel also got into trouble for speaking in support of the boycott. A native of Greenville, Mississippi, in the 8th generation of a line of rabbis, Atlas spent his whole life in the South, except for the years of his rabbinic training. He came to Agudath Israel in 1946, and was well liked in the congregation, serving for several years. Though he grew up with segregation as a way of life, he became a staunch supporter of Civil Rights as the movement picked up momentum in the 1950s.

In 1955, Atlas befriended Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. King enlisted Atlas as his personal Hebrew tutor, and invited the rabbi to speak at his Dexter Avenue Church. Through his involvement with King, Atlas came to empathize with the cause of the boycott. In 1956, as part of Brotherhood week, Atlas agreed to speak on a panel of clergy at WRMA, a local radio station. Reverend Roy Bennett, an African American minister, and Father Michael Caswell, a white priest at Gunter Air Force Base, joined him. The broadcast occurred at the height of the boycott. That week, 90 organizers, among them 24 ministers including Reverend Bennet, were brought into county court on an obscure conspiracy charge. National media swarmed Montgomery. During the Brotherhood panel, a photographer from Life Magazine captured Atlas and Bennett sitting together. When the photograph appeared in the magazine along with an article about the boycott, many members of Agudath Israel flew into a panicked outrage.

Twenty years after Goldstein’s public dissent, the eyes of the country turned to Montgomery for what was a seminal episode in the struggle for civil rights. In December of 1955, with Rosa Parks initiating the first act of protest, the African American community began its year-long bus boycott to demand desegregation of Montgomery’s transit system. As the boycott gained momentum, the city bus system began to lose money, the enrollment of White Citizen’s Councils swelled, and Montgomery Jews watched again from their uncomfortable position as a religious minority within the ruling racial majority.

At this point in Montgomery’s history, the Jewish population had almost completely joined the ranks of its most prominent citizens; important banks and institutions were owned and operated by Jews, and many were active members of the local chapters of the Kiwanis and Masons. Rubin Hanan worked on the staff of Governor Folsom. In fact, Hanan was so ensconced in the ruling power structure that even Admiral John Crommelin an ardent segregationist and outspoken anti-Semite, considered him a friend and colleague. However, Jews still faced exclusion on account of their religion when trying to enter the Montgomery Country Club. Thus, many in the Jewish community, who did not want to face further marginalization, avoided addressing the boycott in any form.

The Jewish spiritual leadership took stands on both sides of the issue. Eugene Blachschlager, the rabbi who had replaced Goldstein at Beth Or, had learned from the example of his predecessor and spoke very little publicly about the boycott. He assured the board of trustees that he had absolutely no connection to the protest or its leadership. He supported them when they sent an angry letter to the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, who had endorsed the boycott. Rabbi Solomon Acrish of Etz Ahayem spoke publically in favor of the movement, citing the demand in the Torah for social justice. Acrish did not continue speaking against segregationist for long, however, as the environment became increasingly hostile. One day he noticed someone following him down the street. A Gentile family, with whom he had long been friends, told him he could not come to their home for dinner anymore because they had been told that Jews supported the boycott. Finally, after Etz Ahayem received a bomb threat by anonymous phone call, Acrish toned down his support of desegregation.

Rabbi Seymour Atlas of Agudath Israel also got into trouble for speaking in support of the boycott. A native of Greenville, Mississippi, in the 8th generation of a line of rabbis, Atlas spent his whole life in the South, except for the years of his rabbinic training. He came to Agudath Israel in 1946, and was well liked in the congregation, serving for several years. Though he grew up with segregation as a way of life, he became a staunch supporter of Civil Rights as the movement picked up momentum in the 1950s.

In 1955, Atlas befriended Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. King enlisted Atlas as his personal Hebrew tutor, and invited the rabbi to speak at his Dexter Avenue Church. Through his involvement with King, Atlas came to empathize with the cause of the boycott. In 1956, as part of Brotherhood week, Atlas agreed to speak on a panel of clergy at WRMA, a local radio station. Reverend Roy Bennett, an African American minister, and Father Michael Caswell, a white priest at Gunter Air Force Base, joined him. The broadcast occurred at the height of the boycott. That week, 90 organizers, among them 24 ministers including Reverend Bennet, were brought into county court on an obscure conspiracy charge. National media swarmed Montgomery. During the Brotherhood panel, a photographer from Life Magazine captured Atlas and Bennett sitting together. When the photograph appeared in the magazine along with an article about the boycott, many members of Agudath Israel flew into a panicked outrage.

The president of Agudath Israel, Yale Friedlander, ordered Atlas to send Life a letter demanding that they rescind the picture and include a correction stating that Brotherhood Week had nothing to do with the boycott. Atlas refused, and explained that he had never explicitly endorsed the boycott in public. Though this might have been the case at the time, soon after his confrontation with Friedlander, Atlas wrote a sermon praying for the participants of the boycott. Before the sermon went to press in the Montgomery Advertiser, as it did every week, a typesetter called one of Agudath’s trustees to warn them. The trustee asked Atlas to edit his sermon, but he refused. Though the actual published sermon turned out to be more about Israel than Montgomery, many were upset by Atlas’ persistent outspokenness. Rumors floated around the congregation that Atlas had accepted a job with the NAACP. While the board discussed the renewal of Atlas’ contract, he argued that it should be an issue decided by a vote of the entire congregation. Despite his protest, the board voted 27 to 1 not to renew Atlas’ term. He and his wife Beverly left Montgomery at the end of his contract in 1956.

On December 20, 1956, after countless miles walked in the heat of the summer and frigid air of winter, with shoes worn through, the Montgomery Bus Boycott came to its official end a month after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Alabama’s segregation laws were unconstitutional. This would not be the end of the struggle for legal equality, nor the last challenge the city of Montgomery would face in dealing with race relations, but it was a major milestone and huge early victory for the Civil Rights Movement. For the Jewish community, it was a time of fear, internal conflict, and eventual acceptance of changing times.

On December 20, 1956, after countless miles walked in the heat of the summer and frigid air of winter, with shoes worn through, the Montgomery Bus Boycott came to its official end a month after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Alabama’s segregation laws were unconstitutional. This would not be the end of the struggle for legal equality, nor the last challenge the city of Montgomery would face in dealing with race relations, but it was a major milestone and huge early victory for the Civil Rights Movement. For the Jewish community, it was a time of fear, internal conflict, and eventual acceptance of changing times.

The Late 20th Century