Kentucky

Overview >> Kentucky

Benjamin Gratz

Benjamin Gratz

Originally part of Virginia, Kentucky broke off to become the country’s fifteenth state in 1792. Overwhelmingly rural in its early years, Kentucky did not attract significant Jewish settlement for several more decades. One of the state’s earliest and most notable Jewish residents was Benjamin Gratz, who moved to Lexington in 1819. Scion of a prominent Jewish family in Philadelphia, Gratz became one of Lexington’s leading citizens during the 19th century. He was one of the founders of the Lexington and Ohio Railroad Company, the state’s first railroad, in 1830. Gratz served on Lexington’s first city council in 1832 and was a director of the first two banks established in the city. He spent 63 years as a trustee of the city’s Transylvania University. Another early Jewish settler was Henry Hyman, who opened a tavern in Louisville called the Western Coffeehouse in 1826. Hyman was perhaps the first Jewish resident in the state’s largest city. By the 1830s, a small but growing number of Jews had settled in Louisville. An Israelite Benevolent Society founded in 1832 dissolved after only four years. Not until 1842 did Louisville Jews establish a lasting congregation, the first in the state. By the time of the Civil War, Louisville was the only city in Kentucky to have a Jewish congregation although Jews lived in several other towns across the state.

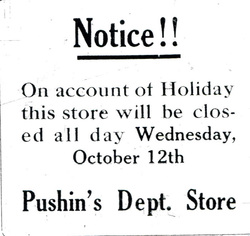

Yom Kippur closing announcement from Bowling Green newspaper, 1921

Yom Kippur closing announcement from Bowling Green newspaper, 1921

The Civil War had a significant impact on Kentucky Jews. Like other Kentuckians, Jews were divided over the war, with some supporting the South while others backed the North. These Union allegiances were severely challenged when General Ulysses S. Grant issued Orders No. 11, which sought to expel all Jews from his military district. This region included western Kentucky, and the small Jewish community in Paducah was forced to leave the area. One Paducah Jew, Cesar Kaskel, decided to lobby the government directly, traveling to Washington, D.C. where he was able to meet with President Lincoln. After hearing Kaskel’s explanation of the situation, the president quickly agreed to overturn the order. Three days later, General Grant’s office sent out notice that the order was revoked. Most of the expelled Paducah Jews returned to the city. Grant’s Order was only enforced for a little over a week.

In the decades after the Civil War, Jews established new congregations in Owensboro (1865), Paducah (1871), Lexington (1877), and Henderson (1887), in addition to several additional ones in Louisville. By 1878, an estimated 3600 Jews lived in the state.

In the decades after the Civil War, Jews established new congregations in Owensboro (1865), Paducah (1871), Lexington (1877), and Henderson (1887), in addition to several additional ones in Louisville. By 1878, an estimated 3600 Jews lived in the state.

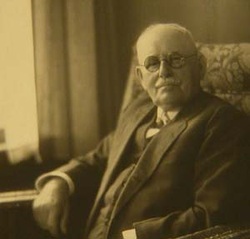

Isaac W. Bernheim

Isaac W. Bernheim

By the late 19th century, a growing number of Jews settled in Kentucky. Most got involved in trade, opening retail stores and wholesale businesses across the state. In 1877, a newspaper in Owensboro noted the proliferation of Jewish-owned stores, claiming that “the city owes much of its commercial reputation to the vim and enterprise of this class of people.” Henry Wallerstein opened a men’s clothing store in Paducah in 1868. In 1888, Wallerstein’s moved to a new three story building, where it remained until it closed almost a century later. Abraham Rothchild opened a clothing store in Shelbyville in 1874 that remained in business for the next 73 years. Brothers Henry and Moses Levy opened a clothing and tailoring business in Louisville in the 1860s. From this small beginning grew the Levy Brothers store, which specialized in men’s clothing, and served Louisville residents for over a century. The Pushin Brothers Department Store, established in the early 1900s, served Bowling Green until it closed in 1978. In Lexington, Dolph Wile and Simon Wolf bought a 20-year-old department store in 1910 and changed its name to the Wolf Wile Company. Dolph’s son Joseph Wile kept the business open until it was the last department store located downtown before it finally closed in 1992.

Newport's United Hebrew Congregation, built in 1905.

Newport's United Hebrew Congregation, built in 1905. Photo courtesy of the American Jewish Archives.

Kentucky Jews were also involved in one of Kentucky’s most famous industries: whiskey distilling. In Paducah, five of the six wholesale liquor firms in 1894 were Jewish owned. Many of these companies eventually moved into distilling. Joseph Friedman started a distillery and wholesale whiskey business with his brother-in-law John Keiler in 1890. Their Paducah distillery became one of the largest in the country, producing 20,000 barrels of whiskey a year. In Louisville, Isaac W. Bernheim purchased a local distillery and later created the I.W. Harper brand of whiskey. After his distillery business became extremely successful, Bernheim became a major philanthropist. Several other Louisville Jews were involved in the liquor trade, especially after prohibition was repealed. Once whiskey was made legal again in 1933, five Shapira brothers, who already owned a department store, invested in a new distillery business. Their Heaven Hill brand is currently the largest family-owned distillery business in the country.

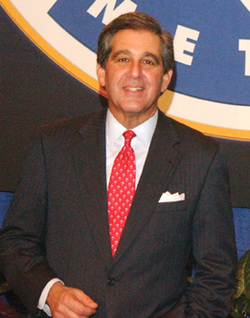

Former Louisville mayor and

Former Louisville mayor and current Lieutenant Governor Jerry Abramson

Around the turn of the century, new congregations were established in Ashland (1896), Newport (1897), Lexington (1903), Middlesboro (1905), Covington (1906), and Hopkinsville (1910). A new wave of Jews from Eastern Europe settled in Kentucky. Louisville saw its Jewish community grow from 2500 people in 1878 to almost 14,000 by 1937. In the early 1920s, Louisville had seven different congregations, several of which were Orthodox synagogues established by recent immigrants. They also created a Vaad Haer, or community council, that supervised and certified the production of kosher meat, ran the mikveh (ritual bath), and established the Louisville Hebrew School. In 1903, the Vaad Haer also hired a chief rabbi for the city, A.L. Zarchy, who became the spiritual leader of all the city’s Orthodox congregations. In Lexington, Orthodox Jews formally established their own separate congregation in 1912 after years of praying together in minyans. In Ashland, a small group of Orthodox Jews founded their own congregation in 1921 rather than joining the town’s Reform congregation. In smaller cities where there weren’t enough Jews to support two congregations, there was often conflict over religious ritual. In Hopkinsville, after local merchant Henry Bohn died in 1923, he left $5000 to the Adath Israel congregation to be used to build a house of worship, with the stipulation that the synagogue be Orthodox. But when Adath Israel member Wolf Geller designed the small neo-classical building, he used the Reform style with the bimah located in the front of the sanctuary.

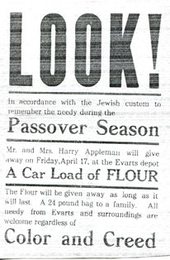

Notice printed by Harry and Bina Appleman

Notice printed by Harry and Bina Appleman offering to help feed striking miners in 1931.

Kentucky Jews have long played leading roles in the political and civic life of the state. In Louisville, lawyer Lewis Dembitz was an early supporter of the Republican Party, serving as a delegate to the party’s 1860 national convention. Dembitz was a strong opponent of slavery and even translated Uncle Tom’s Cabin into German. In the 1880s, Dembitz served four years as the Louisville city attorney. Dembitz was also an intellectual, writing book reviews for the Nation magazine, in addition to several books on the law. In Paducah, Meyer Weil was elected to four terms as mayor in the 1870s. During his tenure, he built a city hospital and led Paducah through the Panic of 1873, helping to restore the city’s credit rating. Later, Weil spent two terms representing Paducah in the state legislature. In Lexington, Moses Kaufman served seventeen years on the city council. Active in the Democratic Party, Kaufman was elected to the state legislature in 1896. In 1915, President Woodrow Wilson appointed Kaufman as postmaster for Lexington. Morris Weintraub of Newport also served in the state legislature, and was the Speaker of the House in 1958. Leon Rothchild served as mayor of Shelbyville from 1912 to 1922. Jews have also been mayors of Middlesboro, Pineville, Somerset, Central City, and Ashland. First elected in 1986, Jerry Abramson served as Louisville’s mayor for over 20 years. Abramson was elected lieutenant governor of Kentucky in 2011. John Yarmuth has represented Louisville in the U.S. House of Representatives since 2007.

The former synagogue of Henderson's Adas Israel congregation

The former synagogue of Henderson's Adas Israel congregation is now a Christian church.

In addition to holding public office, Kentucky Jews have contributed significantly to the larger communities in which they lived. In Owensboro, Theodore Levy, who served as Adath Israel’s spiritual leader, organized the city’s Associated Charities organization in 1915. After he died tragically in 1919, his family donated his house to become a children’s home. In Shelbyville, Moses Ruben left the bulk of his estate to establish a trust fund that supports local projects and charities. Usually, Jewish charity was met with appreciation, but not during the bitter coal strikes in eastern Kentucky. Harry and Bina Appleman, who owned a general store in Evarts, decided to give away 24-pound bags of flour to striking miners in 1931. The coal company did not appreciate the Appleman’s largesse, and swore out a criminal complaint against the couple for criminal syndicalism. Although the charges were eventually dropped, the Applemans left Kentucky after company thugs shot into their home. Perhaps the most visible example of Jewish philanthropy was the establishment of Jewish Hospital in Louisville in 1903 by prominent Jewish businessmen. Although the hospital has a kosher kitchen and mezuzahs on every door, and has been supported financially by the local Jewish community, it has served primarily non-Jews. Today, Jewish Hospital is one of the largest hospitals in the city and is nationally recognized for its medical care.

By 1937, about 18,000 Jews lived in Kentucky, with over 75% residing in Louisville. By mid-century, there were Jewish congregations in eleven different Kentucky cities with new congregations being founded in Harlan (1931) and Danville (1940s). Since then, the state’s Jewish population has shrunk, with congregations closing in Ashland, Newport, Covington, Henderson, Danville, and Hopkinsville. Even Louisville’s Jewish community has shrunk to an estimated 8,300 people in 2006. These declining population trends have affected the entire state, with an estimated 11,300 Jews living in Kentucky in 2011. The only exceptions to this trend are Lexington, which reached an all-time peak of 2,500 Jews in 2009, and Bowling Green, where a small but growing community established the city’s first Jewish congregation in 1999. Both of these cities have large state universities that have attracted a growing number of Jewish faculty and administrators in recent years. In 2010, Eli Capilouto became the first Jewish president of the University of Kentucky.

In 2013, only five cities in Kentucky had Jewish congregations, and only the ones in Lexington and Louisville were thriving. In the future, organized Jewish life in the Bluegrass State may be restricted to its two largest cities.

By 1937, about 18,000 Jews lived in Kentucky, with over 75% residing in Louisville. By mid-century, there were Jewish congregations in eleven different Kentucky cities with new congregations being founded in Harlan (1931) and Danville (1940s). Since then, the state’s Jewish population has shrunk, with congregations closing in Ashland, Newport, Covington, Henderson, Danville, and Hopkinsville. Even Louisville’s Jewish community has shrunk to an estimated 8,300 people in 2006. These declining population trends have affected the entire state, with an estimated 11,300 Jews living in Kentucky in 2011. The only exceptions to this trend are Lexington, which reached an all-time peak of 2,500 Jews in 2009, and Bowling Green, where a small but growing community established the city’s first Jewish congregation in 1999. Both of these cities have large state universities that have attracted a growing number of Jewish faculty and administrators in recent years. In 2010, Eli Capilouto became the first Jewish president of the University of Kentucky.

In 2013, only five cities in Kentucky had Jewish congregations, and only the ones in Lexington and Louisville were thriving. In the future, organized Jewish life in the Bluegrass State may be restricted to its two largest cities.