Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Louisiana

Overview >> Louisiana

Louisiana consists of very distinct regions and cultures, from the Catholic Cajuns in the southern part of the state and the Protestants in the north, to the unique cultural gumbo of New Orleans. While the state is certainly part of the South, its history and development have marked it as different from the rest of the region. Much of this difference stems from the French influence, which remains apparent today. One can still hear Cajun patois on Acadiana radio stations while the legal system in Louisiana is still based on the Napoleonic Code instead of English Common Law. The French influence also shaped the state’s Jewish history, as many Alsatian Jews were drawn to the area in the 19th century because of its cultural familiarity. While they have always been a tiny religious minority, Louisiana Jews have been a vital part of the state and its unique cultures for 250 years.

When writing about Jews in Louisiana, it’s easy to focus too much on New Orleans, which has long overshadowed the state and region’s Jewish community. As the largest Jewish community in Louisiana, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Alabama, New Orleans has played a leading role in the economic and religious development of smaller Jewish communities throughout the region. Indeed, a majority of Louisiana’s Jews has always lived in the Crescent City. But a significant minority has lived in northern cities like Shreveport and Monroe, taking an active role in those cities’ civic life. In southern Louisiana, often known as Acadiana due to its Cajun influence, Jews formed small congregations that thrived amidst the Catholic majority. With the decline of Jewish communities in small cities and towns in recent decades, New Orleans remains the center of Jewish life in the state, although Hurricane Katrina has increased the prominence of Baton Rouge.

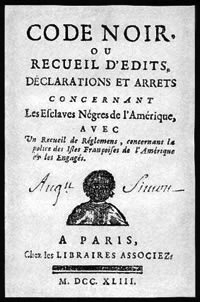

Jews were not welcome in the French colony of Louisiana, known then as New France. France had expelled all Jews from within its borders and its colonies in 1394 for a period that lasted until the French Revolution in 1789. In 1724, King Louis XV ordered that his administration in Louisiana adopt the Code Noir, which declared that Roman Catholicism would be the only religion practiced in the colonies. The first article of the edict concerns Jews specifically, ordering that French officers “chase from our islands all the Jews who established residence there. As with all declared enemies of Christianity, we command them to be gone…at the risk of confiscation of their persons and goods.” Despite this edict’s harsh language, it was rarely enforced in colonial Louisiana, so when Isaac Monsanto arrived in New Orleans in 1757, he was able to establish a successful trading business. After Spain acquired Louisiana, the new colonial governor enforced this prohibition, deporting Monsanto and his cohorts from the area, although they eventually returned. When President Thomas Jefferson negotiated the 1803 Louisiana Purchase with Napoleon and Louisiana came under American jurisdiction, Jews acquired the right to freely inhabit what would become the 18th state in the Union.

19th century Jews in Louisiana embraced this freedom and in many cases became part of the state’s ruling elite. At the time of the Civil War, Jews held several important political offices in Louisiana. Dr. Edwin Moise was speaker of the state house and had earlier served as Attorney General. Henry Hyams had been elected Lieutenant Governor in 1859. Judah P. Benjamin was one Louisiana’s U.S. Senators and later became an important cabinet official in the Confederacy. This political role continued even after the war. Benjamin Franklin Jonas, who was a Confederate veteran, represented New Orleans in the state legislature from 1865 to 1868. He later served as the New Orleans City attorney in the 1870s, before spending a term in the U.S. Senate from 1879 to 1885. Adolph Meyer, who also fought for the South during the Civil War, was elected to the US House of Representatives in 1890, and served until his death in 1908. This political role has continued into the 21st century: Jay Dardenne was elected as Louisiana’s Secretary of State in 2006.

The first hundred years of Jewish history in Louisiana was centered in New Orleans. In the 18th century, a handful of Sephardic Jews from other new world colonies like Curacao settled in the city located at the mouth of the Mississippi River, although they made no efforts to organize Jewish communal institutions. The Jewish population of New Orleans grew in the early 19th century as immigrants from Alsace and the German states began to settle there. In 1828, New Orleans Jews organized the state’s first congregation, Gates of Mercy. By 1855, New Orleans had three synagogues, two Jewish benevolent associations, and a Jewish orphanage. There were no other congregations in the state at the time.

When writing about Jews in Louisiana, it’s easy to focus too much on New Orleans, which has long overshadowed the state and region’s Jewish community. As the largest Jewish community in Louisiana, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Alabama, New Orleans has played a leading role in the economic and religious development of smaller Jewish communities throughout the region. Indeed, a majority of Louisiana’s Jews has always lived in the Crescent City. But a significant minority has lived in northern cities like Shreveport and Monroe, taking an active role in those cities’ civic life. In southern Louisiana, often known as Acadiana due to its Cajun influence, Jews formed small congregations that thrived amidst the Catholic majority. With the decline of Jewish communities in small cities and towns in recent decades, New Orleans remains the center of Jewish life in the state, although Hurricane Katrina has increased the prominence of Baton Rouge.

Jews were not welcome in the French colony of Louisiana, known then as New France. France had expelled all Jews from within its borders and its colonies in 1394 for a period that lasted until the French Revolution in 1789. In 1724, King Louis XV ordered that his administration in Louisiana adopt the Code Noir, which declared that Roman Catholicism would be the only religion practiced in the colonies. The first article of the edict concerns Jews specifically, ordering that French officers “chase from our islands all the Jews who established residence there. As with all declared enemies of Christianity, we command them to be gone…at the risk of confiscation of their persons and goods.” Despite this edict’s harsh language, it was rarely enforced in colonial Louisiana, so when Isaac Monsanto arrived in New Orleans in 1757, he was able to establish a successful trading business. After Spain acquired Louisiana, the new colonial governor enforced this prohibition, deporting Monsanto and his cohorts from the area, although they eventually returned. When President Thomas Jefferson negotiated the 1803 Louisiana Purchase with Napoleon and Louisiana came under American jurisdiction, Jews acquired the right to freely inhabit what would become the 18th state in the Union.

19th century Jews in Louisiana embraced this freedom and in many cases became part of the state’s ruling elite. At the time of the Civil War, Jews held several important political offices in Louisiana. Dr. Edwin Moise was speaker of the state house and had earlier served as Attorney General. Henry Hyams had been elected Lieutenant Governor in 1859. Judah P. Benjamin was one Louisiana’s U.S. Senators and later became an important cabinet official in the Confederacy. This political role continued even after the war. Benjamin Franklin Jonas, who was a Confederate veteran, represented New Orleans in the state legislature from 1865 to 1868. He later served as the New Orleans City attorney in the 1870s, before spending a term in the U.S. Senate from 1879 to 1885. Adolph Meyer, who also fought for the South during the Civil War, was elected to the US House of Representatives in 1890, and served until his death in 1908. This political role has continued into the 21st century: Jay Dardenne was elected as Louisiana’s Secretary of State in 2006.

The first hundred years of Jewish history in Louisiana was centered in New Orleans. In the 18th century, a handful of Sephardic Jews from other new world colonies like Curacao settled in the city located at the mouth of the Mississippi River, although they made no efforts to organize Jewish communal institutions. The Jewish population of New Orleans grew in the early 19th century as immigrants from Alsace and the German states began to settle there. In 1828, New Orleans Jews organized the state’s first congregation, Gates of Mercy. By 1855, New Orleans had three synagogues, two Jewish benevolent associations, and a Jewish orphanage. There were no other congregations in the state at the time.

Over the next five years, Jewish immigrants from Alsace and the German states settled in communities around the state. Many came through New Orleans, which was the country’s second largest immigration port in the decades before the Civil War. By 1861, perhaps as many as 8,000 Jews lived in Louisiana and congregations had been established in Donaldsonville, Shreveport, Baton Rouge, Monroe, and Alexandria. With the exception of Donaldsonville, these cities would remain the centers of Jewish population in Louisiana well into the 20th century. Many of those who settled in these communities began as peddlers and ended up as small town merchants, supplied by Jewish wholesalers in New Orleans. Much of the 19th century Jewish settlements in Louisiana and Mississippi were economic outposts of New Orleans.

Louisiana Jews played a remarkable role in the state’s economic development. Leon Godchaux, in addition to owning a large clothing store in New Orleans, helped to revolutionize the state’ sugar industry in the years after the Civil War by using more modern and efficient production techniques. Godchaux became the largest sugar producer in the South. Abrom Kaplan played a similar role in southern Louisiana’s rice industry. Jews also had a hand in some of the more distinctive Louisiana industries. Jacques Weil and his brothers made Rayne the frog capital of the world with their successful business that shipped 10,000 pounds of frog legs around the country each week. In New Orleans, Joseph Haspel popularized the seersucker suit, which soon became synonymous with the hot and sticky summers of the Deep South.

After the Civil War, Jewish immigrants from central Europe continued to settle around the state, and they were soon joined by immigrants from the Russian Empire and Eastern Europe. During the last thirty years of the 19th century, Jews established congregations in Natchitoches, Morgan City, Opelousas, Bastrop, Plaquemine, Lafayette, Lecompte, St. Francisville, Lake Charles, and New Iberia. Of these congregations, only those in Cajun country (Lake Charles, Lafayette, and New Iberia) still remain active today. In larger communities like New Orleans, Shreveport, and Alexandria, Eastern European Jews established their own Orthodox congregations.

During the early 20th century, Louisiana Jews began to concentrate more in the larger cities of the state. Congregations in St. Francisville, Lecompte, Bastrop, and Natchitoches all became defunct in the first quarter of the 20th century, as residents moved to Shreveport, New Orleans, or elsewhere, and new immigrants bypassed these small towns. In 1937, 15,000 Jews lived in Louisiana, well over half of which lived in New Orleans. At the time, other significant Jewish communities (over 50 people) included: Alexandria, Baton Rouge, Bogalusa, Crowley, Donaldsonville, Houma, Lafayette, Lake Charles, Lake Providence, Monroe, Morgan City, New Iberia, Opelousas, Plaquemine, and Shreveport.

Over the years, Louisiana Jews have made a significant mark on their communities and the state. In Shreveport, four Jews have served as mayor. Several Louisiana Jews have been elected to the state legislature and the US Congress. They have become leading philanthropists throughout the state, especially in New Orleans, where facing exclusion from elite social organizations, they have focused their time and resources on civic improvement. While Jews have enjoyed overall acceptance in the state, they have had to face occasional anti-Semitism. In the early 1990s, former Ku Klux Klan leader David Duke launched a briefly successful political career in Lousiana. Several activists organized against Duke, including Holocaust survivor Anne Levy, who helped to thwart his efforts to win statewide elective office.

In recent decades, as in the rest of the South, smaller towns and cities have experienced a decline in their Jewish population. Shreveport and Monroe had 3,400 Jews combined in 1960, but only about 800 today. Alexandria had over 700 Jews in 1980, but only 175 today. Prior to Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans had about 10,000 Jews, down from about 12,000 in 1984. After the storm, only about 70% of the Jewish population has resettled in the city. Baton Rouge, which only had 1,600 Jews on the eve of the storm, has seen a significant increase in the size of its Jewish population. Although predictions that Baton Rouge would soon outstrip New Orleans as the largest city in the state did not come to pass. New Orleans remains the largest Jewish community in the state, and its ability to recover and rebuild from Katrina will profoundly shape the future of Louisiana Jewry.

Louisiana Jews played a remarkable role in the state’s economic development. Leon Godchaux, in addition to owning a large clothing store in New Orleans, helped to revolutionize the state’ sugar industry in the years after the Civil War by using more modern and efficient production techniques. Godchaux became the largest sugar producer in the South. Abrom Kaplan played a similar role in southern Louisiana’s rice industry. Jews also had a hand in some of the more distinctive Louisiana industries. Jacques Weil and his brothers made Rayne the frog capital of the world with their successful business that shipped 10,000 pounds of frog legs around the country each week. In New Orleans, Joseph Haspel popularized the seersucker suit, which soon became synonymous with the hot and sticky summers of the Deep South.

After the Civil War, Jewish immigrants from central Europe continued to settle around the state, and they were soon joined by immigrants from the Russian Empire and Eastern Europe. During the last thirty years of the 19th century, Jews established congregations in Natchitoches, Morgan City, Opelousas, Bastrop, Plaquemine, Lafayette, Lecompte, St. Francisville, Lake Charles, and New Iberia. Of these congregations, only those in Cajun country (Lake Charles, Lafayette, and New Iberia) still remain active today. In larger communities like New Orleans, Shreveport, and Alexandria, Eastern European Jews established their own Orthodox congregations.

During the early 20th century, Louisiana Jews began to concentrate more in the larger cities of the state. Congregations in St. Francisville, Lecompte, Bastrop, and Natchitoches all became defunct in the first quarter of the 20th century, as residents moved to Shreveport, New Orleans, or elsewhere, and new immigrants bypassed these small towns. In 1937, 15,000 Jews lived in Louisiana, well over half of which lived in New Orleans. At the time, other significant Jewish communities (over 50 people) included: Alexandria, Baton Rouge, Bogalusa, Crowley, Donaldsonville, Houma, Lafayette, Lake Charles, Lake Providence, Monroe, Morgan City, New Iberia, Opelousas, Plaquemine, and Shreveport.

Over the years, Louisiana Jews have made a significant mark on their communities and the state. In Shreveport, four Jews have served as mayor. Several Louisiana Jews have been elected to the state legislature and the US Congress. They have become leading philanthropists throughout the state, especially in New Orleans, where facing exclusion from elite social organizations, they have focused their time and resources on civic improvement. While Jews have enjoyed overall acceptance in the state, they have had to face occasional anti-Semitism. In the early 1990s, former Ku Klux Klan leader David Duke launched a briefly successful political career in Lousiana. Several activists organized against Duke, including Holocaust survivor Anne Levy, who helped to thwart his efforts to win statewide elective office.

In recent decades, as in the rest of the South, smaller towns and cities have experienced a decline in their Jewish population. Shreveport and Monroe had 3,400 Jews combined in 1960, but only about 800 today. Alexandria had over 700 Jews in 1980, but only 175 today. Prior to Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans had about 10,000 Jews, down from about 12,000 in 1984. After the storm, only about 70% of the Jewish population has resettled in the city. Baton Rouge, which only had 1,600 Jews on the eve of the storm, has seen a significant increase in the size of its Jewish population. Although predictions that Baton Rouge would soon outstrip New Orleans as the largest city in the state did not come to pass. New Orleans remains the largest Jewish community in the state, and its ability to recover and rebuild from Katrina will profoundly shape the future of Louisiana Jewry.