Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - New Orleans, Louisiana

New Orleans: Historical Overview

|

Three hundred years ago, when the first French settlers arrived in present-day Louisiana, they encountered an altogether new world. The forbidding and untamed landscape teemed with tropical diseases and inhospitable insects. The dense, overgrown swamps seemed to embody the absolute antithesis of the cultured old world these settlers left behind. The region also bore unsurpassed promise. Seated at the gateway to perhaps the most fertile agricultural region in the world, and serviced by a river system that reached across half the continent, the fledgling settlement would in time bestow untold riches upon those bold enough to battle the hostile natural landscape.

In 1718, Governor Bienville moved the capital of the Louisiana Colony from Mobile to a sheltered bend of the Mississippi River which he named New Orleans, in honor of King Phillip II, the Duke of Orleans. As a revolving litany of world powers struggled to lay claim to the region and the crescent city, the New Orleanians preserved a fiercely independent character as the flags of six successive ruling powers flapped above the city in the muggy coastal air. More than other American cities, New Orleans experienced a unique mingling of the old world and the new, a city steeped in traditions and ancient hierarchies but bustling with the hum of modern American capitalism. The predominance of Catholicism and a racially and ethnically mixed population have helped instill a carefree culture of independence and individualism in New Orleans. For 250 years, Jews have thrived in this culture, profiting from the Crescent City’s promise and creating an experience unparalleled in other American cities. |

Stories of the Jewish Community in New Orleans

The Colonial Period

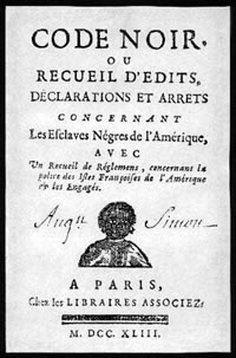

If French colonial laws had been strictly enforced, there would be no history of Jews in 18th century New Orleans at all. According to the Code Noire, promulgated in 1724, Jews were excluded from the French territory of Louisiana. Yet, as was often the case with American colonies of European nations, colonists were more focused on developing trade in the region than following the strictures of royal courts thousands of miles away. From the colonists’ perspective, Jews had useful experience and connections in shipping and commerce. So when Isaac Monsanto and his business partner Manuel de Britto, two Sephardic Jews, arrived in New Orleans from Curacao in 1757, they faced few if any legal restrictions as they built a successful trading business. Monsanto sued in the colonial court, bought and sold property, and even worked as a court translator. Six of his siblings soon joined Isaac in New Orleans.

This relative freedom was temporarily restricted after France ceded the area west of the Mississippi River to Spain. In 1769, the new colonial governor Don Alejandro O’Reilly ordered the Monsantos, Britto, and other Jews in New Orleans to leave the city because “they are undesirables on account of the nature of their business and of the religion they profess.” It was no accident that Governor O’Reilly mentioned business first in his order since removing three successful merchants seemed to be his primary motivation as he tried to ensure that Spain controlled the New Orleans trade. The Monsantos dispersed, some moving to Pensacola and others to Manchac at the junction of the Mississippi and Iberville rivers, where the family tried to reestablish its business. Eventually, they were quietly allowed to return to New Orleans, although they never regained their once prominent position in the city’s trade.

These Jewish colonial pioneers did nothing to build a Jewish community in New Orleans. They intermarried and never founded a synagogue. According to Bertram Korn, there were Jews in colonial New Orleans, but no Judaism. This trend would continue during the first few decades of the 19th century.

If French colonial laws had been strictly enforced, there would be no history of Jews in 18th century New Orleans at all. According to the Code Noire, promulgated in 1724, Jews were excluded from the French territory of Louisiana. Yet, as was often the case with American colonies of European nations, colonists were more focused on developing trade in the region than following the strictures of royal courts thousands of miles away. From the colonists’ perspective, Jews had useful experience and connections in shipping and commerce. So when Isaac Monsanto and his business partner Manuel de Britto, two Sephardic Jews, arrived in New Orleans from Curacao in 1757, they faced few if any legal restrictions as they built a successful trading business. Monsanto sued in the colonial court, bought and sold property, and even worked as a court translator. Six of his siblings soon joined Isaac in New Orleans.

This relative freedom was temporarily restricted after France ceded the area west of the Mississippi River to Spain. In 1769, the new colonial governor Don Alejandro O’Reilly ordered the Monsantos, Britto, and other Jews in New Orleans to leave the city because “they are undesirables on account of the nature of their business and of the religion they profess.” It was no accident that Governor O’Reilly mentioned business first in his order since removing three successful merchants seemed to be his primary motivation as he tried to ensure that Spain controlled the New Orleans trade. The Monsantos dispersed, some moving to Pensacola and others to Manchac at the junction of the Mississippi and Iberville rivers, where the family tried to reestablish its business. Eventually, they were quietly allowed to return to New Orleans, although they never regained their once prominent position in the city’s trade.

These Jewish colonial pioneers did nothing to build a Jewish community in New Orleans. They intermarried and never founded a synagogue. According to Bertram Korn, there were Jews in colonial New Orleans, but no Judaism. This trend would continue during the first few decades of the 19th century.

The 19th Century

The most influential yet ambivalent figure in the early 19th century New Orleans Jewish community was Judah Touro. While he had little direct connection with the nascent community, through his philanthropy, he left a mark on New Orleans Jewish life that is still visible today. Raised in Rhode Island, where his father was the leader of the Newport congregation, Touro arrived in New Orleans in 1801. Using his contacts in New England, Touro built a successful trading businesses as a broker and wholesaler of goods made in the northeast and Europe. Touro purchased a lot of property in New Orleans as the city emerged as a commercial center of the American South. During the Battle of New Orleans, Touro fought heroically and suffered a serious wound. After his injury, Touro became a recluse, rarely venturing out in public as he continued to manage his significant financial interests.

Touro was not involved in the founding of the city’s first Jewish congregation, and at first seemed more interested in supporting local Christian churches. He had bought a pew in a local Episcopal Church and bought the building of First Presbyterian Church so the congregation would not be evicted. Despite his isolation from the city’s growing Jewish community, Touro donated a building for use as a synagogue by a new congregation Dispersed of Judah. Late in his life, Touro began to offer more financial support to Jewish institutions in the city. He helped the Gates of Mercy congregation in their fundraising drive to build a synagogue. In 1854, he established Touro Infirmary, a charity hospital supported by the local Hebrew Benevolent Association. When Touro died in 1854, his will included many donations to Jewish institutions around the country, including New Orleans. He gave over $100,000 to Jewish causes in New Orleans. Touro, who had little contact with the organized Jewish community during his lifetime, had become the first great Jewish philanthropist, whose largesse benefited congregations across the country.

Touro was just one of several Jewish merchants who settled in New Orleans in the first few decades of the 19th century. Although they were a tiny minority, Jews faced few social or legal barriers. After Louisiana became a part of the United States, Jews benefited from the religious and political freedoms enshrined in the Constitution. Alexander Phillips came in 1808, and became a successful businessman. He served three terms as alderman in the 1820s, becoming the first Jew to be elected to office in New Orleans. These Jewish men also enjoyed enough social acceptance that marrying Christian women became commonplace. Benjamin Levy came to New Orleans in 1811, becoming a local book printer. He married a Catholic woman from a prominent local family whose brother served as mayor of New Orleans. Indeed, in the early 19th century, a marriage between two Jews was a rare occurrence, as these early settlers did not produce a lasting Jewish community.

The most influential yet ambivalent figure in the early 19th century New Orleans Jewish community was Judah Touro. While he had little direct connection with the nascent community, through his philanthropy, he left a mark on New Orleans Jewish life that is still visible today. Raised in Rhode Island, where his father was the leader of the Newport congregation, Touro arrived in New Orleans in 1801. Using his contacts in New England, Touro built a successful trading businesses as a broker and wholesaler of goods made in the northeast and Europe. Touro purchased a lot of property in New Orleans as the city emerged as a commercial center of the American South. During the Battle of New Orleans, Touro fought heroically and suffered a serious wound. After his injury, Touro became a recluse, rarely venturing out in public as he continued to manage his significant financial interests.

Touro was not involved in the founding of the city’s first Jewish congregation, and at first seemed more interested in supporting local Christian churches. He had bought a pew in a local Episcopal Church and bought the building of First Presbyterian Church so the congregation would not be evicted. Despite his isolation from the city’s growing Jewish community, Touro donated a building for use as a synagogue by a new congregation Dispersed of Judah. Late in his life, Touro began to offer more financial support to Jewish institutions in the city. He helped the Gates of Mercy congregation in their fundraising drive to build a synagogue. In 1854, he established Touro Infirmary, a charity hospital supported by the local Hebrew Benevolent Association. When Touro died in 1854, his will included many donations to Jewish institutions around the country, including New Orleans. He gave over $100,000 to Jewish causes in New Orleans. Touro, who had little contact with the organized Jewish community during his lifetime, had become the first great Jewish philanthropist, whose largesse benefited congregations across the country.

Touro was just one of several Jewish merchants who settled in New Orleans in the first few decades of the 19th century. Although they were a tiny minority, Jews faced few social or legal barriers. After Louisiana became a part of the United States, Jews benefited from the religious and political freedoms enshrined in the Constitution. Alexander Phillips came in 1808, and became a successful businessman. He served three terms as alderman in the 1820s, becoming the first Jew to be elected to office in New Orleans. These Jewish men also enjoyed enough social acceptance that marrying Christian women became commonplace. Benjamin Levy came to New Orleans in 1811, becoming a local book printer. He married a Catholic woman from a prominent local family whose brother served as mayor of New Orleans. Indeed, in the early 19th century, a marriage between two Jews was a rare occurrence, as these early settlers did not produce a lasting Jewish community.

Early Organized Jewish Life in New Orleans

By 1822, there were 25 Jews living in New Orleans, yet they had not yet organized a congregation. Jacob Solis, who was visiting for business from New York in 1827, was shocked that he was unable to find matzoh in New Orleans for Passover. Solis decided to organize the growing Jewish community of the Crescent City. Under his leadership, in December of 1827, 33 Jews founded Shaarai Chesed (Gates of Mercy), America’s first congregation outside of the original 13 states. Of these founding members, only three were married to Jews. Reflecting the reality of intermarriage, the congregation’s bylaws allowed the non-Jewish spouses of members to be buried in the Jewish cemetery. Children of non-Jewish mothers were also allowed to join the congregation. These dramatic departures from Jewish law reflected the pragmatic compromises these Jews made to the unique circumstances of early Jewish life in New Orleans.

Even the most pious of Jews were not immune to the demographic reality of a relative lack of Jewish women. Manis Jacobs had a strong Jewish identity, using his Hebrew name as part of his letter seal. When his first wife, who was Jewish, died, he remarried a Catholic woman. Nevertheless, he remained an active member of the Gates of Mercy congregation, serving as its first president and often leading services. While intermarriage was common, conversion to Christianity was relatively rare, as these Jews retained a strong sense of Jewishness. The growth of New Orleans’ Jewish population in the 1830s made this tolerance of intermarriage less necessary. By 1841, Gates of Mercy had changed its bylaws and now denied membership to men who had married out of the faith.

By 1822, there were 25 Jews living in New Orleans, yet they had not yet organized a congregation. Jacob Solis, who was visiting for business from New York in 1827, was shocked that he was unable to find matzoh in New Orleans for Passover. Solis decided to organize the growing Jewish community of the Crescent City. Under his leadership, in December of 1827, 33 Jews founded Shaarai Chesed (Gates of Mercy), America’s first congregation outside of the original 13 states. Of these founding members, only three were married to Jews. Reflecting the reality of intermarriage, the congregation’s bylaws allowed the non-Jewish spouses of members to be buried in the Jewish cemetery. Children of non-Jewish mothers were also allowed to join the congregation. These dramatic departures from Jewish law reflected the pragmatic compromises these Jews made to the unique circumstances of early Jewish life in New Orleans.

Even the most pious of Jews were not immune to the demographic reality of a relative lack of Jewish women. Manis Jacobs had a strong Jewish identity, using his Hebrew name as part of his letter seal. When his first wife, who was Jewish, died, he remarried a Catholic woman. Nevertheless, he remained an active member of the Gates of Mercy congregation, serving as its first president and often leading services. While intermarriage was common, conversion to Christianity was relatively rare, as these Jews retained a strong sense of Jewishness. The growth of New Orleans’ Jewish population in the 1830s made this tolerance of intermarriage less necessary. By 1841, Gates of Mercy had changed its bylaws and now denied membership to men who had married out of the faith.

The Growth of Business and Industry

After the Louisiana Purchase, which made New Orleans part of the burgeoning United States, the city’s population exploded. In 1815, 10,000 people lived in New Orleans; by 1840, over 100,000 did. Between 1820 and 1860, New Orleans was the second largest immigrant port in the United States. In the decade before the Civil War, 250,000 immigrants came through the port of New Orleans. By 1860, an estimated 2,000 Jews lived in New Orleans, which had become one of the largest commercial centers in the country. Agricultural goods from the Midwest and the South were sent down the Mississippi River to New Orleans, while finished goods from the Northeast and Europe were shipped upriver to communities across the region.

Jewish merchants, who had close business and personal contacts with other Jews in the northeast, took advantage of New Orleans’s location to amass large fortunes in trade in the mid-19th century. According to the historian Elliot Ashkenazi, there were 245 different Jewish owned businesses in New Orleans between 1841 and 1861. Over half of these businesses dealt in clothing or dry goods. New Orleans merchants usually operated both a retail business in the city and a wholesale business supplying peddlers and Jewish-owned stores in small towns in the region. Successful merchants often became cotton factors, buying cotton in New Orleans and shipping it to New York. They would purchase dry goods and clothing in exchange, which they brought back to New Orleans and sold to storekeepers across the region. There were often strong social and kinship ties between New Orleans suppliers and Jewish merchants in rural areas of Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama. Large wholesalers in New Orleans would offer credit to small town Jewish merchants, who often could not get it from financial institutions. Credit was an essential commodity in the cash-strapped South, in which farmers and merchants only got paid after the harvest came in. New Orleans became the commercial hub for the entire Deep South.

Leon Godchaux’s life reflected the economic opportunities available to enterprising Jews in New Orleans during this period. Godchaux came to the city from Lorraine in 1840, starting out as a pack peddler selling ribbons, needles, yarn, and thread. Leopold Jonas, a Jewish merchant, fronted him his first supply of merchandise, and Godchaux traveled upriver visiting farms that had no access to market towns. Godchaux was very successful and soon acquired a horse and wagon, selling to both large plantations and small farmers. He eventually opened a store in Convent, Louisiana, 50 miles north of New Orleans. Soon, he decided to try his luck in the big city, opening “Leon Godchaux, French and American Clothier” in New Orleans in 1844. The following year, he brought his family from Europe and his brother joined him in the business. His store was profitable and soon expanded. He also established a wholesale business that supplied small town and rural storeowners in the region. By the time of the Civil War, Godchaux’s was the largest and most successful clothing business in the city.

Godchaux also transformed the sugar industry in Louisiana. When he was a peddler, Godchaux noticed how inefficient sugar plantations were, and yearned for a chance to improve their production techniques. When the Civil War decimated the local sugar industry, Godchaux was able to purchase several sugar plantations at a discount, some of which he had peddled at twenty years earlier. Godchaux brought modern capitalist techniques to his sugar operation, using wage labor instead of slaves, and centralizing the cane processing. At his peak, he owned 10,000 acres of sugar cane fields and was the largest sugar producer in the South. According to one writer, Godchaux “was the most important person in the economy of [Louisiana] in the 19th century.” Despite his sugar fortune, Godchaux maintained his clothing store, which remained under the family’s control until it closed in 1986. Godchaux, with his successful retail and wholesale clothing business, along with his sugar operation, embodied the commercial spirit of the new South that arose upon the ashes of the old plantation society.

Like Leon Godchaux, other Jews established major downtown stores in New Orleans. Isidore Newman came to the city from Germany in 1880. In 1897, he established the Maison Blanche store, which became one of the largest department stores on Canal Street, which ran through the city’s downtown business district. Leon Heymann moved to New Orleans in 1920 after achieving commercial success in several small towns in southern Louisiana. He married a sister of the Krauss brothers, who had founded Krauss Department store in 1903, soon becoming president of the company. The Krauss Department Store remained a Canal Street retail emporium until it closed in 1997.

After the Louisiana Purchase, which made New Orleans part of the burgeoning United States, the city’s population exploded. In 1815, 10,000 people lived in New Orleans; by 1840, over 100,000 did. Between 1820 and 1860, New Orleans was the second largest immigrant port in the United States. In the decade before the Civil War, 250,000 immigrants came through the port of New Orleans. By 1860, an estimated 2,000 Jews lived in New Orleans, which had become one of the largest commercial centers in the country. Agricultural goods from the Midwest and the South were sent down the Mississippi River to New Orleans, while finished goods from the Northeast and Europe were shipped upriver to communities across the region.

Jewish merchants, who had close business and personal contacts with other Jews in the northeast, took advantage of New Orleans’s location to amass large fortunes in trade in the mid-19th century. According to the historian Elliot Ashkenazi, there were 245 different Jewish owned businesses in New Orleans between 1841 and 1861. Over half of these businesses dealt in clothing or dry goods. New Orleans merchants usually operated both a retail business in the city and a wholesale business supplying peddlers and Jewish-owned stores in small towns in the region. Successful merchants often became cotton factors, buying cotton in New Orleans and shipping it to New York. They would purchase dry goods and clothing in exchange, which they brought back to New Orleans and sold to storekeepers across the region. There were often strong social and kinship ties between New Orleans suppliers and Jewish merchants in rural areas of Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama. Large wholesalers in New Orleans would offer credit to small town Jewish merchants, who often could not get it from financial institutions. Credit was an essential commodity in the cash-strapped South, in which farmers and merchants only got paid after the harvest came in. New Orleans became the commercial hub for the entire Deep South.

Leon Godchaux’s life reflected the economic opportunities available to enterprising Jews in New Orleans during this period. Godchaux came to the city from Lorraine in 1840, starting out as a pack peddler selling ribbons, needles, yarn, and thread. Leopold Jonas, a Jewish merchant, fronted him his first supply of merchandise, and Godchaux traveled upriver visiting farms that had no access to market towns. Godchaux was very successful and soon acquired a horse and wagon, selling to both large plantations and small farmers. He eventually opened a store in Convent, Louisiana, 50 miles north of New Orleans. Soon, he decided to try his luck in the big city, opening “Leon Godchaux, French and American Clothier” in New Orleans in 1844. The following year, he brought his family from Europe and his brother joined him in the business. His store was profitable and soon expanded. He also established a wholesale business that supplied small town and rural storeowners in the region. By the time of the Civil War, Godchaux’s was the largest and most successful clothing business in the city.

Godchaux also transformed the sugar industry in Louisiana. When he was a peddler, Godchaux noticed how inefficient sugar plantations were, and yearned for a chance to improve their production techniques. When the Civil War decimated the local sugar industry, Godchaux was able to purchase several sugar plantations at a discount, some of which he had peddled at twenty years earlier. Godchaux brought modern capitalist techniques to his sugar operation, using wage labor instead of slaves, and centralizing the cane processing. At his peak, he owned 10,000 acres of sugar cane fields and was the largest sugar producer in the South. According to one writer, Godchaux “was the most important person in the economy of [Louisiana] in the 19th century.” Despite his sugar fortune, Godchaux maintained his clothing store, which remained under the family’s control until it closed in 1986. Godchaux, with his successful retail and wholesale clothing business, along with his sugar operation, embodied the commercial spirit of the new South that arose upon the ashes of the old plantation society.

Like Leon Godchaux, other Jews established major downtown stores in New Orleans. Isidore Newman came to the city from Germany in 1880. In 1897, he established the Maison Blanche store, which became one of the largest department stores on Canal Street, which ran through the city’s downtown business district. Leon Heymann moved to New Orleans in 1920 after achieving commercial success in several small towns in southern Louisiana. He married a sister of the Krauss brothers, who had founded Krauss Department store in 1903, soon becoming president of the company. The Krauss Department Store remained a Canal Street retail emporium until it closed in 1997.

Organized Jewish Life Develops

Jewish religious life in New Orleans was slow to develop. The first congregation was not organized until 1828, several decades after Jews began to settle in New Orleans in sufficient numbers. By the 1830s, there were perhaps a few hundred Jews living in the city. During the next decade, the Jewish community of New Orleans began to organize key institutions. Gershom Kursheedt, who came to New Orleans in 1840, played an important role in the community’s development. While previous Jewish settlers expressed little interest in maintaining traditional Judaism, Kursheedt had studied with the esteemed Rabbi Isaac Leeser, and quickly worked to organize local Jews. While he originally joined the congregation Gates of Mercy, Kursheedt helped to form a new congregation, Dispersed of Judah, in 1845. Some have suggested that Kursheedt named the congregation as a way to entice the support of New Orleans’ most famous Judah, and indeed Touro gave the new group a building to use as a synagogue. For the synagogue’s dedication, Kursheedt brought down his old mentor, Rabbi Leeser, to lead the festivities. Another group of Jews living in the suburb of Lafayette (now part of the New Orleans Garden District), organized the congregation Shaarei Tefila (Gates of Prayer) in 1850.

This flurry of congregation founding continued through the 19th century. In 1858, the city’s growing number of Polish Jewish immigrants established Tememe Derech (The Right Way). In 1875, other Eastern European Jews founded Chevra Thilim, which remained an Orthodox congregation until the late 20th century. In 1870, the city’s elite German Jews founded Temple Sinai, the first congregation in New Orleans founded as Reform. By 1872, it had built an impressive synagogue just off Tivoli Circle (now Lee Circle) which reflected the status of its membership. Many members of Gates of Mercy left to join Temple Sinai, leaving New Orleans’ first congregation in financial trouble. In 1881, it merged with Dispersed of Judah to form what’s now called Touro Synagogue.

As the community grew, Jews established institutions to care for those in need. Judah Touro’s bequest created the Touro Infirmary in 1854 as a charity hospital to care for the city’s indigent sick. The Hebrew Benevolent Association was an early financial supporter of the infirmary, and merged with the hospital in 1874. New Orleans Jews have helped to support the private hospital throughout its long history. New Orleans suffered a series of yellow fever outbreaks during the 19th century. In response, local Jews founded the Association for the Relief of Widows and Orphans in 1854. Two years later, it built a home for these unfortunates. By 1865, 50 Jewish children from across the South lived in the home. In 1875, the Deep South region of B’nai B’rith became a major sponsor of the orphanage. In 1881, they built a new larger home on St. Charles Avenue, which served Jewish orphans until the late 1940s.

Jewish religious life in New Orleans was slow to develop. The first congregation was not organized until 1828, several decades after Jews began to settle in New Orleans in sufficient numbers. By the 1830s, there were perhaps a few hundred Jews living in the city. During the next decade, the Jewish community of New Orleans began to organize key institutions. Gershom Kursheedt, who came to New Orleans in 1840, played an important role in the community’s development. While previous Jewish settlers expressed little interest in maintaining traditional Judaism, Kursheedt had studied with the esteemed Rabbi Isaac Leeser, and quickly worked to organize local Jews. While he originally joined the congregation Gates of Mercy, Kursheedt helped to form a new congregation, Dispersed of Judah, in 1845. Some have suggested that Kursheedt named the congregation as a way to entice the support of New Orleans’ most famous Judah, and indeed Touro gave the new group a building to use as a synagogue. For the synagogue’s dedication, Kursheedt brought down his old mentor, Rabbi Leeser, to lead the festivities. Another group of Jews living in the suburb of Lafayette (now part of the New Orleans Garden District), organized the congregation Shaarei Tefila (Gates of Prayer) in 1850.

This flurry of congregation founding continued through the 19th century. In 1858, the city’s growing number of Polish Jewish immigrants established Tememe Derech (The Right Way). In 1875, other Eastern European Jews founded Chevra Thilim, which remained an Orthodox congregation until the late 20th century. In 1870, the city’s elite German Jews founded Temple Sinai, the first congregation in New Orleans founded as Reform. By 1872, it had built an impressive synagogue just off Tivoli Circle (now Lee Circle) which reflected the status of its membership. Many members of Gates of Mercy left to join Temple Sinai, leaving New Orleans’ first congregation in financial trouble. In 1881, it merged with Dispersed of Judah to form what’s now called Touro Synagogue.

As the community grew, Jews established institutions to care for those in need. Judah Touro’s bequest created the Touro Infirmary in 1854 as a charity hospital to care for the city’s indigent sick. The Hebrew Benevolent Association was an early financial supporter of the infirmary, and merged with the hospital in 1874. New Orleans Jews have helped to support the private hospital throughout its long history. New Orleans suffered a series of yellow fever outbreaks during the 19th century. In response, local Jews founded the Association for the Relief of Widows and Orphans in 1854. Two years later, it built a home for these unfortunates. By 1865, 50 Jewish children from across the South lived in the home. In 1875, the Deep South region of B’nai B’rith became a major sponsor of the orphanage. In 1881, they built a new larger home on St. Charles Avenue, which served Jewish orphans until the late 1940s.

The Civil War

Ironically, much of this development of Jewish institutions in New Orleans was due to the effects of the Civil War, which brought many Jews from surrounding rural areas into the relative safety of the city. Most Jews in New Orleans were loyal supporters of the Confederacy, and several took up arms for the cause. When the Union Army captured New Orleans in 1862, they forced local citizens to take a loyalty oath to the United States or else be deported to the Confederacy. Rabbi James Gutheim, the spiritual leader of the Dispersed of Judah congregation, refused to pronounce his loyalty to the Union, declaring the South’s cause to be one “of right and justice.” Rather than compromise, Gutheim left New Orleans, settling in Montgomery, Alabama, where he served as rabbi of the local congregation. His refusal to pledge support for the Union made Gutheim a hero to Jews in the South. Interestingly, his pro-Confederate views did not dissuade Temple Emanu-El in New York from hiring him as their rabbi in 1868. Gutheim eventually returned to New Orleans in 1872 to lead the newly formed Temple Sinai.

It’s not surprising that New Orleans Jews were such strong supporters of the Southern cause. By the time of the war, several had become a part of the city’s ruling elite as they enjoyed tremendous acceptance in the predominately Catholic city. When Louisiana seceded, New Orleans Jews held several prominent political positions in the state. Dr. Edwin Moise was speaker of the state house and had earlier served as Attorney General. Henry Hyams had been elected Lieutenant Governor in 1859. This political role continued even after the war. Benjamin Franklin Jonas, who was a Confederate veteran, represented New Orleans in the state legislature from 1865 to 1868. He later served as the New Orleans City attorney in the 1870s, before spending a term in the U.S. Senate from 1879 to 1885. Adolph Meyer, who also fought for the South during the Civil War, was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1890, and served until his death in 1908.

The most famous Jewish officeholder from New Orleans was Judah P. Benjamin, who was one of the state’s senators at the time of secession and later became an important cabinet official in the Confederacy. Born in the Dutch West Indies, Benjamin came to New Orleans in 1827. He became a lawyer and later bought a sugar plantation outside of the city. In 1852, the state legislature elected him to be a US senator. Benjamin greatly enjoyed his time in the senate, even turning down an appointment to the US Supreme Court in 1853 in order to remain in the legislative branch. While in the senate, Benjamin was an outspoken defender of slavery and the South, and soon joined the Confederate government after secession. He first served as the Attorney General, and then later as Secretary of War. From 1862 until the end of the war, Benjamin served as the Secretary of State for the Confederacy, focusing much of his effort on trying to coax Great Britain into the war on the South’s side. Benjamin was unsuccessful in this endeavor, and the Confederacy eventually fell. After the war, Benjamin fled the country to England, becoming a successful barrister. He never returned to the United States. Benjamin was indicative of the early Jews of New Orleans: he intermarried and had no affiliation with any Jewish organization.

Ironically, much of this development of Jewish institutions in New Orleans was due to the effects of the Civil War, which brought many Jews from surrounding rural areas into the relative safety of the city. Most Jews in New Orleans were loyal supporters of the Confederacy, and several took up arms for the cause. When the Union Army captured New Orleans in 1862, they forced local citizens to take a loyalty oath to the United States or else be deported to the Confederacy. Rabbi James Gutheim, the spiritual leader of the Dispersed of Judah congregation, refused to pronounce his loyalty to the Union, declaring the South’s cause to be one “of right and justice.” Rather than compromise, Gutheim left New Orleans, settling in Montgomery, Alabama, where he served as rabbi of the local congregation. His refusal to pledge support for the Union made Gutheim a hero to Jews in the South. Interestingly, his pro-Confederate views did not dissuade Temple Emanu-El in New York from hiring him as their rabbi in 1868. Gutheim eventually returned to New Orleans in 1872 to lead the newly formed Temple Sinai.

It’s not surprising that New Orleans Jews were such strong supporters of the Southern cause. By the time of the war, several had become a part of the city’s ruling elite as they enjoyed tremendous acceptance in the predominately Catholic city. When Louisiana seceded, New Orleans Jews held several prominent political positions in the state. Dr. Edwin Moise was speaker of the state house and had earlier served as Attorney General. Henry Hyams had been elected Lieutenant Governor in 1859. This political role continued even after the war. Benjamin Franklin Jonas, who was a Confederate veteran, represented New Orleans in the state legislature from 1865 to 1868. He later served as the New Orleans City attorney in the 1870s, before spending a term in the U.S. Senate from 1879 to 1885. Adolph Meyer, who also fought for the South during the Civil War, was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1890, and served until his death in 1908.

The most famous Jewish officeholder from New Orleans was Judah P. Benjamin, who was one of the state’s senators at the time of secession and later became an important cabinet official in the Confederacy. Born in the Dutch West Indies, Benjamin came to New Orleans in 1827. He became a lawyer and later bought a sugar plantation outside of the city. In 1852, the state legislature elected him to be a US senator. Benjamin greatly enjoyed his time in the senate, even turning down an appointment to the US Supreme Court in 1853 in order to remain in the legislative branch. While in the senate, Benjamin was an outspoken defender of slavery and the South, and soon joined the Confederate government after secession. He first served as the Attorney General, and then later as Secretary of War. From 1862 until the end of the war, Benjamin served as the Secretary of State for the Confederacy, focusing much of his effort on trying to coax Great Britain into the war on the South’s side. Benjamin was unsuccessful in this endeavor, and the Confederacy eventually fell. After the war, Benjamin fled the country to England, becoming a successful barrister. He never returned to the United States. Benjamin was indicative of the early Jews of New Orleans: he intermarried and had no affiliation with any Jewish organization.

Growth in the Jewish Community

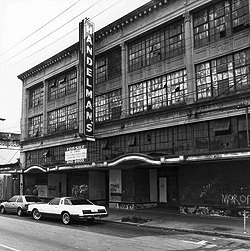

The earlier pattern of intermarriage and unaffiliation faded after the Civil War, as new immigrants flocked to New Orleans. In 1860, about 2,000 Jews lived in New Orleans. By the end of the 19th century, over 5,000 did. Many of these newcomers were immigrants from Eastern Europe, who established their own community largely distinct from the Alsatian and German Jews who had moved “uptown” around the turn of the century. Eastern European Jews began arriving in small numbers in the mid-19th century, founding their own small Orthodox congregation in 1858. As this wave increased in the late 19th century, Jews formed several small ethnic-based congregations in the Dryades Street area, which became the primary Jewish immigrant neighborhood in the city. There was a Galitzianer shul, a Litvak shul, a Polish shul, and so on. Many of these small congregations did not have a permanent building, and several of them merged in 1904 to form the Orthodox congregation Beth Israel. Jews opened various retail businesses along Dryades Street, which was dotted with kosher delis and meat markets as well as Jewish-owned dry goods and department stores like Handelman's. The neighborhood was racially mixed, and Jewish merchants on Dryades Street catered to African Americans as well as fellow Jews. This pattern of Jewish immigrant settlement is similar to that in other American cities around the turn of the century. What makes New Orleans unusual is the fact that Orthodox Eastern European Jews never outnumbered the Reform “German Uptown” Jews, who continued to dominate the New Orleans Jewish community throughout the 20th century.

The earlier pattern of intermarriage and unaffiliation faded after the Civil War, as new immigrants flocked to New Orleans. In 1860, about 2,000 Jews lived in New Orleans. By the end of the 19th century, over 5,000 did. Many of these newcomers were immigrants from Eastern Europe, who established their own community largely distinct from the Alsatian and German Jews who had moved “uptown” around the turn of the century. Eastern European Jews began arriving in small numbers in the mid-19th century, founding their own small Orthodox congregation in 1858. As this wave increased in the late 19th century, Jews formed several small ethnic-based congregations in the Dryades Street area, which became the primary Jewish immigrant neighborhood in the city. There was a Galitzianer shul, a Litvak shul, a Polish shul, and so on. Many of these small congregations did not have a permanent building, and several of them merged in 1904 to form the Orthodox congregation Beth Israel. Jews opened various retail businesses along Dryades Street, which was dotted with kosher delis and meat markets as well as Jewish-owned dry goods and department stores like Handelman's. The neighborhood was racially mixed, and Jewish merchants on Dryades Street catered to African Americans as well as fellow Jews. This pattern of Jewish immigrant settlement is similar to that in other American cities around the turn of the century. What makes New Orleans unusual is the fact that Orthodox Eastern European Jews never outnumbered the Reform “German Uptown” Jews, who continued to dominate the New Orleans Jewish community throughout the 20th century.

Notable New Orleans Jews

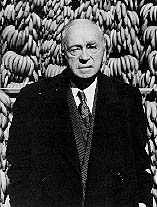

Several New Orleans Jews became national and even international business leaders. No New Orleanian exercised more power in the Western Hemisphere than Sam Zemurray. Born in Russia, Zemurray came to the United States in 1891 at the age of 14. He first settled in Selma, Alabama and later moved to Mobile where he sold bananas as a peddler to small town grocers. Fruit would prove to be very lucrative for Zemurray, who became known as the “Banana Man.” He eventually moved to New Orleans and established the Cuyamel Fruit Company. He later bought land in Honduras to grow bananas. When he didn’t like the Honduran government’s tax policies, Zemurray helped to organize and fund a successful coup, which installed a new government that was far more supportive of his business interests. He remained an active player in Central American politics for decades. Zemurray sold his company to the larger United Fruit Company in 1929. Three years later, Zemurray led a shareholder revolt that resulted in his becoming managing director and later president of the company. Zemurray built UFC into an economic and political power in the region.

Samuel and Emanuel Pulitzer both grew up in the New Orleans Children’s Home. Remarkably, from these humble beginnings they went on to establish the Wembley Tie Company, which became the largest tie manufacturing company in the world. Joseph Haspel owned a clothing company that started to make seersucker suits in 1909. The light fabric was perfect for the heat and humidity of New Orleans and the South. Due to Haspel, Seersucker suits became synonymous with the South. In 1905, Gustave Katz and Sydney Besthoff opened a drug store in New Orleans. K&B Drugs eventually became a major pharmacy chain in the region. When the company was sold to Rite-Aid in 1997, it had 186 stores. Malcolm Woldenberg and Stephen Goldring founded the Magnolia Marketing Company in 1944, which soon became a very successful liquor and wine distributing company. With its carefree party atmosphere, New Orleans was certainly a good territory for their business. Goldring and Woldenberg became leading philanthropists in New Orleans, supporting many Jewish and non-Jewish causes and institutions.

New Orleans Jews have also left their mark on the professions. Before the Civil War, Elizabeth Cohen was the first female physician in Louisiana. After having five children, she went to medical school in Philadelphia. She came to New Orleans in 1857, and worked alongside male doctors during several yellow fever epidemics. Cohen was a family doctor who delivered two generations of babies in New Orleans.

Local Jews have had a long association with Tulane University, which today boasts a large Jewish student population. This relationship goes back to the 19th century, when Herman Kohlmeyer was a longtime professor of Hebrew and Oriental Literature. Kohlmeyer was an esteemed Jewish scholar who sometimes filled in as a temporary rabbi at both Gates of Mercy and Dispersed of Judah. Several Jews shaped the state’s architecture. Moise Goldstein designed the New Orleans airport, Dillard University, and many other prominent buildings in the city. Leon Weiss became Governor Huey Long’s favorite architect, and designed the new state capitol in Baton Rouge.

The colorful Long worked closely with a number of Jewish political allies, though this relationship often didn’t end too well for them. Abraham Shushan was a political advisor for Long, who appointed him to be president of the New Orleans Levee Board in 1929. Long originally named the New Orleans airport after Shusan, though the name was later changed after Shushan was charged with corruption and tax evasion. Seymour Weiss owned a New Orleans hotel, but was best known as the “prime minister” of the Long political machine of the 1920s. After Long’s assassination in 1935, Weiss tried to keep the machine alive. He was later convicted of mail fraud and tax evasion and spent 16 months in prison. While the careers of Shushan and Weiss ended in woe, they show how closely integrated Jews were in the city and state’s political power structure.

Several New Orleans Jews became national and even international business leaders. No New Orleanian exercised more power in the Western Hemisphere than Sam Zemurray. Born in Russia, Zemurray came to the United States in 1891 at the age of 14. He first settled in Selma, Alabama and later moved to Mobile where he sold bananas as a peddler to small town grocers. Fruit would prove to be very lucrative for Zemurray, who became known as the “Banana Man.” He eventually moved to New Orleans and established the Cuyamel Fruit Company. He later bought land in Honduras to grow bananas. When he didn’t like the Honduran government’s tax policies, Zemurray helped to organize and fund a successful coup, which installed a new government that was far more supportive of his business interests. He remained an active player in Central American politics for decades. Zemurray sold his company to the larger United Fruit Company in 1929. Three years later, Zemurray led a shareholder revolt that resulted in his becoming managing director and later president of the company. Zemurray built UFC into an economic and political power in the region.

Samuel and Emanuel Pulitzer both grew up in the New Orleans Children’s Home. Remarkably, from these humble beginnings they went on to establish the Wembley Tie Company, which became the largest tie manufacturing company in the world. Joseph Haspel owned a clothing company that started to make seersucker suits in 1909. The light fabric was perfect for the heat and humidity of New Orleans and the South. Due to Haspel, Seersucker suits became synonymous with the South. In 1905, Gustave Katz and Sydney Besthoff opened a drug store in New Orleans. K&B Drugs eventually became a major pharmacy chain in the region. When the company was sold to Rite-Aid in 1997, it had 186 stores. Malcolm Woldenberg and Stephen Goldring founded the Magnolia Marketing Company in 1944, which soon became a very successful liquor and wine distributing company. With its carefree party atmosphere, New Orleans was certainly a good territory for their business. Goldring and Woldenberg became leading philanthropists in New Orleans, supporting many Jewish and non-Jewish causes and institutions.

New Orleans Jews have also left their mark on the professions. Before the Civil War, Elizabeth Cohen was the first female physician in Louisiana. After having five children, she went to medical school in Philadelphia. She came to New Orleans in 1857, and worked alongside male doctors during several yellow fever epidemics. Cohen was a family doctor who delivered two generations of babies in New Orleans.

Local Jews have had a long association with Tulane University, which today boasts a large Jewish student population. This relationship goes back to the 19th century, when Herman Kohlmeyer was a longtime professor of Hebrew and Oriental Literature. Kohlmeyer was an esteemed Jewish scholar who sometimes filled in as a temporary rabbi at both Gates of Mercy and Dispersed of Judah. Several Jews shaped the state’s architecture. Moise Goldstein designed the New Orleans airport, Dillard University, and many other prominent buildings in the city. Leon Weiss became Governor Huey Long’s favorite architect, and designed the new state capitol in Baton Rouge.

The colorful Long worked closely with a number of Jewish political allies, though this relationship often didn’t end too well for them. Abraham Shushan was a political advisor for Long, who appointed him to be president of the New Orleans Levee Board in 1929. Long originally named the New Orleans airport after Shusan, though the name was later changed after Shushan was charged with corruption and tax evasion. Seymour Weiss owned a New Orleans hotel, but was best known as the “prime minister” of the Long political machine of the 1920s. After Long’s assassination in 1935, Weiss tried to keep the machine alive. He was later convicted of mail fraud and tax evasion and spent 16 months in prison. While the careers of Shushan and Weiss ended in woe, they show how closely integrated Jews were in the city and state’s political power structure.

Jews in New Orleans Social and Civic Life

Despite their political, professional and business success, New Orleans Jews have long faced exclusion from the city’s elite social circles. Ironically, this anti-Semitism has given Jews an opportunity to have a profound impact on the civic institutions of New Orleans. In New Orleans through much of the 20th century, high society revolved around a handful of elite social clubs and Mardi Gras krewes. The wealthy and influential Gentiles of New Orleans belong to places like the Boston Club and Pickwick Club and to the elite krewes like Comus and Rex. Each year during Mardi Gras, these krewes throw elaborate balls in which young women debut. In the mid-19th century, Jews were members of the elite social clubs; they were even among the founders of the Pickwick Club. Even the first king of Mardi Gras in 1872, Lewis Salomon, was Jewish. In the late 19th century, with the rise of elitist anti-Semitism around the country, and the influx of new Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, Jews were excluded from the highest rungs of the New Orleans social hierarchy. Even today, Jews are still not welcome in some of the elite krewes or at their parties.

Jews have dealt with these barriers in various ways. First, they created their own separate social clubs. In 1872, they founded the Harmony Club, which mirrored the older elite Gentile clubs. Indeed, the old Harmony Club building on Canal Street is currently the home of the Boston Club. In 1891, they created a Young Men’s Hebrew Association and constructed a building known as the Athenaeum on St. Charles Avenue. Ironically, the courts of Rex and Comus held their Mardi Gras meeting ritual in the Athenaeum Ballroom. The YMHA offered several activities that catered to both the uptown German Jewish community as well as the Orthodox Eastern European community, including athletic programs for kids. In recent years, Jews have even founded their own Mardi Gras krewes and taken part in the festivities’ parades.

New Orleans Jews have also dealt with this exclusion by focusing their time and money on the city’s civic institutions rather than expensive and elaborate balls. Wealthy Jews have long been prominent in the charitable and cultural institutions in the city. Such philanthropy offered them a forum to express their social status while gaining prestige for the Jewish community. Felix Dreyfous was born and raised in New Orleans. A graduate of Tulane Law School, Dreyfous was elected to the state legislature, where he fought corruption and worked to improve flood control. Dreyfous was a successful lawyer, and created City Park in 1891. Isaac Delgado was a dealer in sugar and molasses, and amassed a large fortune in the late 19th century. In 1911, he built a public art museum in City Park now known as the New Orleans Museum of Art. Isidore Newman helped to form the New Orleans Stock Exchange and served as its longtime president. Newman gave the money to establish the Isidore Newman Manual Training School in 1903, which was originally designed to educate students who lived in the Jewish Children’s Home. It soon grew into the city’s most respected college prep school.

Edgar Stern was named the outstanding philanthropist of the 20th century by the New Orleans States-Item for his support of local institutions. His wife, Edith Rosenwald Stern, was also involved in many local causes; together they founded the Stern Fund, which supported local charities. A major patron of the arts, Lucile Jacoby Blum founded the Louisiana Council of Music and the Performing Arts and the Louisiana State Arts Council. Each year, the New Orleans Times Picayune awards the “Loving Cup” to honor civic leaders who have made a big difference in New Orleans. Since they began giving the prize in 1901, Jews have won a sizable minority of the awards, an amazing feat considering they have constituted less than 2% of the city’s population.

Despite their political, professional and business success, New Orleans Jews have long faced exclusion from the city’s elite social circles. Ironically, this anti-Semitism has given Jews an opportunity to have a profound impact on the civic institutions of New Orleans. In New Orleans through much of the 20th century, high society revolved around a handful of elite social clubs and Mardi Gras krewes. The wealthy and influential Gentiles of New Orleans belong to places like the Boston Club and Pickwick Club and to the elite krewes like Comus and Rex. Each year during Mardi Gras, these krewes throw elaborate balls in which young women debut. In the mid-19th century, Jews were members of the elite social clubs; they were even among the founders of the Pickwick Club. Even the first king of Mardi Gras in 1872, Lewis Salomon, was Jewish. In the late 19th century, with the rise of elitist anti-Semitism around the country, and the influx of new Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, Jews were excluded from the highest rungs of the New Orleans social hierarchy. Even today, Jews are still not welcome in some of the elite krewes or at their parties.

Jews have dealt with these barriers in various ways. First, they created their own separate social clubs. In 1872, they founded the Harmony Club, which mirrored the older elite Gentile clubs. Indeed, the old Harmony Club building on Canal Street is currently the home of the Boston Club. In 1891, they created a Young Men’s Hebrew Association and constructed a building known as the Athenaeum on St. Charles Avenue. Ironically, the courts of Rex and Comus held their Mardi Gras meeting ritual in the Athenaeum Ballroom. The YMHA offered several activities that catered to both the uptown German Jewish community as well as the Orthodox Eastern European community, including athletic programs for kids. In recent years, Jews have even founded their own Mardi Gras krewes and taken part in the festivities’ parades.

New Orleans Jews have also dealt with this exclusion by focusing their time and money on the city’s civic institutions rather than expensive and elaborate balls. Wealthy Jews have long been prominent in the charitable and cultural institutions in the city. Such philanthropy offered them a forum to express their social status while gaining prestige for the Jewish community. Felix Dreyfous was born and raised in New Orleans. A graduate of Tulane Law School, Dreyfous was elected to the state legislature, where he fought corruption and worked to improve flood control. Dreyfous was a successful lawyer, and created City Park in 1891. Isaac Delgado was a dealer in sugar and molasses, and amassed a large fortune in the late 19th century. In 1911, he built a public art museum in City Park now known as the New Orleans Museum of Art. Isidore Newman helped to form the New Orleans Stock Exchange and served as its longtime president. Newman gave the money to establish the Isidore Newman Manual Training School in 1903, which was originally designed to educate students who lived in the Jewish Children’s Home. It soon grew into the city’s most respected college prep school.

Edgar Stern was named the outstanding philanthropist of the 20th century by the New Orleans States-Item for his support of local institutions. His wife, Edith Rosenwald Stern, was also involved in many local causes; together they founded the Stern Fund, which supported local charities. A major patron of the arts, Lucile Jacoby Blum founded the Louisiana Council of Music and the Performing Arts and the Louisiana State Arts Council. Each year, the New Orleans Times Picayune awards the “Loving Cup” to honor civic leaders who have made a big difference in New Orleans. Since they began giving the prize in 1901, Jews have won a sizable minority of the awards, an amazing feat considering they have constituted less than 2% of the city’s population.

The Jewish Community in New Orleans Today

Over the last few decades, the Jewish community of New Orleans has changed along with the rest of the Jewish South. New Orleans has not experienced the economic boom of the Sunbelt South, losing many of its major corporations to nearby cities like Houston. Yet, because of its important port and its thriving tourism industry, New Orleans has remained a significant city in the region, and thus its Jewish community has not suffered decline in recent decades. Prior to Hurricane Katrina, its Jewish population had remained fairly steady since 1960, when it numbered 10,000 residents. As in the rest of the South, New Orleans Jews have largely moved out of the retail industry and into the professions. Of the great Jewish-owned retail emporiums on Canal Street, only a few stores remain.

Hurricane Katrina in 2005 was an epochal event in the history of the city, and has reshaped the New Orleans Jewish community. As of the second anniversary of the storm, only about 70% of the city’s pre-Katrina Jewish population had returned. While most synagogues escaped serious damage, with the notable exception of Beth Israel which found its building devastated, many Jews suffered flooding in their homes. After Katrina, the Jewish community struggled to maintain all of these institutions and began to organize an effort to bring back old residents and attract new ones through cash incentives and free loans. Like the rest of the city, the New Orleans Jewish community initially faced an uncertain future, but has come together with their neighbors to rebuild and sustain their community. While some displaced Katrina families left and re-settled in places like Houston, the vast majority stayed or returned to the Crescent City. The New Orleans Jewish community has maintained and renewed its vibrant identity, and today sustains multiple active congregations, a Jewish Community Center, a Federation, an active Hillel at Tulane University, and more.

Hurricane Katrina in 2005 was an epochal event in the history of the city, and has reshaped the New Orleans Jewish community. As of the second anniversary of the storm, only about 70% of the city’s pre-Katrina Jewish population had returned. While most synagogues escaped serious damage, with the notable exception of Beth Israel which found its building devastated, many Jews suffered flooding in their homes. After Katrina, the Jewish community struggled to maintain all of these institutions and began to organize an effort to bring back old residents and attract new ones through cash incentives and free loans. Like the rest of the city, the New Orleans Jewish community initially faced an uncertain future, but has come together with their neighbors to rebuild and sustain their community. While some displaced Katrina families left and re-settled in places like Houston, the vast majority stayed or returned to the Crescent City. The New Orleans Jewish community has maintained and renewed its vibrant identity, and today sustains multiple active congregations, a Jewish Community Center, a Federation, an active Hillel at Tulane University, and more.