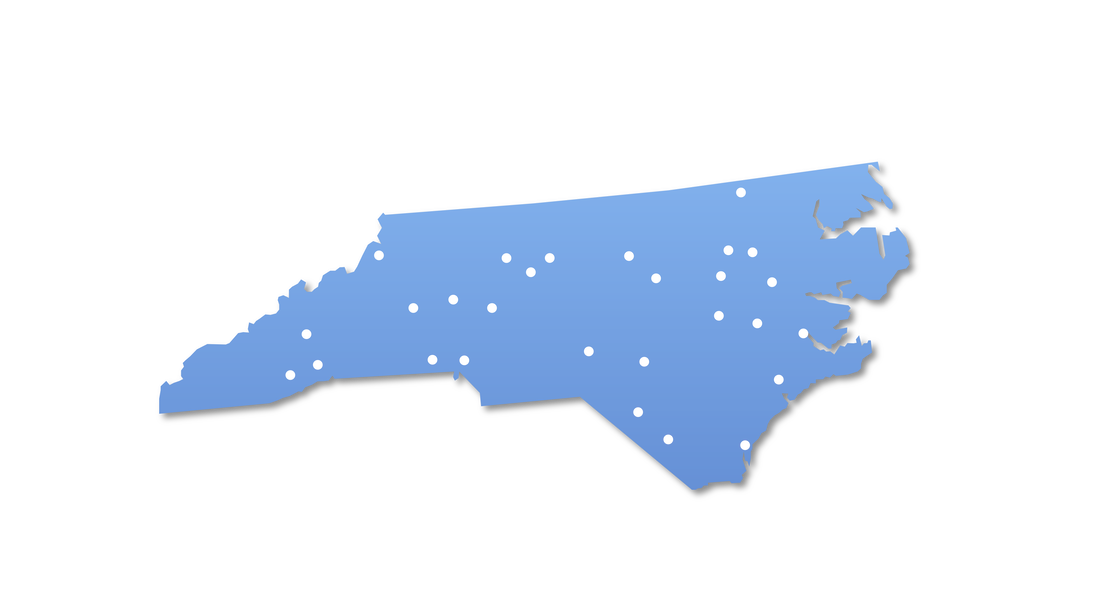

Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - North Carolina

Overview >> North Carolina

Bon Marche Department Store in Asheville

Bon Marche Department Store in Asheville

North Carolina developed later than most other of America’s original thirteen states. Unlike its neighbors, South Carolina and Virginia, North Carolina never developed a significant city during the colonial or early Republic era. Its Jewish communities were also late in developing. While Virginia, South Carolina, and Georgia each had a Jewish congregation by 1790, Jews did not establish one in North Carolina until 1867.

Although organized Jewish life did not begin in North Carolina until after the Civil War, Jews had been living in the state for many decades. Jacob Mordecai was a successful merchant in Warrenton by the 1790s. Abraham Moses and Solomon Simons lived in Charlotte in 1790. By 1800, a handful of native-born Jewish merchants from cities like Newport, Rhode Island, New York, and Charleston lived in Wilmington. By 1822, 31 Jews lived in New Bern. Despite this early settlement, these Jewish pioneers had little access to organized Jewish life. Several of Wilmington’s Jews were members of St. James Episcopal Church, even though they did not identify as Christians. Despite their involvement with the church, Wilmington Jews still had a strong attachment to their Jewishness. Aaron Lazarus observed the Jewish Sabbath at his home, and many of these Wilmington Jews undertook the difficult and expensive process of burying their dead in Jewish cemeteries in faraway cities. Sometimes, this remoteness led to conversion. Moses and George Mordecai of Raleigh both became Episcopalian in the early 1800s.

Although organized Jewish life did not begin in North Carolina until after the Civil War, Jews had been living in the state for many decades. Jacob Mordecai was a successful merchant in Warrenton by the 1790s. Abraham Moses and Solomon Simons lived in Charlotte in 1790. By 1800, a handful of native-born Jewish merchants from cities like Newport, Rhode Island, New York, and Charleston lived in Wilmington. By 1822, 31 Jews lived in New Bern. Despite this early settlement, these Jewish pioneers had little access to organized Jewish life. Several of Wilmington’s Jews were members of St. James Episcopal Church, even though they did not identify as Christians. Despite their involvement with the church, Wilmington Jews still had a strong attachment to their Jewishness. Aaron Lazarus observed the Jewish Sabbath at his home, and many of these Wilmington Jews undertook the difficult and expensive process of burying their dead in Jewish cemeteries in faraway cities. Sometimes, this remoteness led to conversion. Moses and George Mordecai of Raleigh both became Episcopalian in the early 1800s.

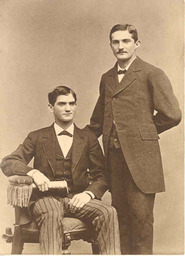

Moses & Ceasar Cone

Moses & Ceasar Cone

Organized Jewish life in North Carolina began in the years after the Civil War. During this era, Jews established congregations in Wilmington (1867), Raleigh (1874), Tarboro (1877), Statesville (1883), Goldsboro (1883), Durham (1886), Winston-Salem (1888) Asheville (1891), New Bern (1893), and Charlotte (1895). The first congregations in Raleigh and Winston-Salem were short-lived, and permanent congregations were not founded in either city until 1912.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Jewish immigrants scattered throughout the state. Many started as peddlers, often outfitted by the Baltimore Bargain House. Later, they established businesses in numerous towns across North Carolina. In Goldsboro, brothers Henry, Herman, and Solomon Weil opened H. Weil & Brothers store in 1865. They later started a wholesale operation that supplied stores throughout the Carolinas. William Heilig and Max Meyers started out peddling to the farmers in the countryside outside of Goldsboro. In 1913, they opened a furniture store together in Goldsboro which later grew into one of the largest furniture store chains in the country. During the late 19th century, David and Isaac Wallace built a thriving medicinal herb business in Statesville. Solomon Lipinsky opened a small dry goods store in Asheville in 1887 that later grew into the Bon Marche Department Store, which remained a downtown fixture through ninety years and three generations of Lipinskys. Jonas & David Oettinger established J&D Oettinger in Wilson in 1882. Later called Oettinger’s – The Dependable Store, it became one of the largest department stores in the area. In Hickory, the arrival of Jewish merchant Louis Zerden in 1908 was a cause for local celebration, as the local newspaper later noted that his decision to settle in town was proof that Hickory had a bright economic future. North Carolina Jews have continued to establish thriving retail businesses in recent decades. Leon Levine of Charlotte built his Family Dollar Store, opened in 1959, into one of the largest retail chains in the country.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Jewish immigrants scattered throughout the state. Many started as peddlers, often outfitted by the Baltimore Bargain House. Later, they established businesses in numerous towns across North Carolina. In Goldsboro, brothers Henry, Herman, and Solomon Weil opened H. Weil & Brothers store in 1865. They later started a wholesale operation that supplied stores throughout the Carolinas. William Heilig and Max Meyers started out peddling to the farmers in the countryside outside of Goldsboro. In 1913, they opened a furniture store together in Goldsboro which later grew into one of the largest furniture store chains in the country. During the late 19th century, David and Isaac Wallace built a thriving medicinal herb business in Statesville. Solomon Lipinsky opened a small dry goods store in Asheville in 1887 that later grew into the Bon Marche Department Store, which remained a downtown fixture through ninety years and three generations of Lipinskys. Jonas & David Oettinger established J&D Oettinger in Wilson in 1882. Later called Oettinger’s – The Dependable Store, it became one of the largest department stores in the area. In Hickory, the arrival of Jewish merchant Louis Zerden in 1908 was a cause for local celebration, as the local newspaper later noted that his decision to settle in town was proof that Hickory had a bright economic future. North Carolina Jews have continued to establish thriving retail businesses in recent decades. Leon Levine of Charlotte built his Family Dollar Store, opened in 1959, into one of the largest retail chains in the country.

Gertrude Weil

Gertrude Weil

During the early 20th century, Jews established congregations in Kinston (1903) Greensboro (1908), Lumberton (1908), Fayetteville (1910), Weldon (1912), Gastonia (1913), Wilson (1921), Rocky Mount (early 1920s), Hendersonville (1922), and High Point (1923). During this period, North Carolina became an industrial center, especially for textiles and furniture. Several Jews played a key role in the state’s industrial development. Frank Goldberg owned several cotton mills in Gastonia in the first half of the 20th century. In Greensboro, Moses and Ceasar Cone established the Proximity Cotton Mills in 1895 while Herman and Emanuel Sternberger created the Revolution Cotton Mill. The Cones and Sternbergers became the industrial titans of Greensboro, transforming the city into a center of the textile industry. Both families made numerous contributions to civic life in Greensboro.

Jews have played an active role in the state’s civic life since the earliest days of Jewish settlement. Jacob Henry of Beaufort was elected to the North Carolina House of Commons in 1808, when all office holders were required to take a Christian oath. When he was challenged by another member of the House, Henry delivered an impassioned speech defending religious liberty in America. Moved by his oratory (or convinced by a narrow legal argument) the legislature allowed Henry to take his rightful seat. North Carolina did not remove the Christian oath requirement until 1868. Once this impediment was removed, Jews were elected to office around the state. In Wilmington, Sol Fishblate was elected alderman in 1873 and mayor five years later. Fishblate was elected mayor once again in 1891 during a time of white supremacist backlash. With his fellow Democrats, Fishblate argued that whites should control the local government, and supported the violent riot that overturned “black rule” in the city in 1898. In the Civil Rights era, Mutt Evans helped to lead Durham toward peaceful integration during his twelve years as mayor. B.D. Schwartz helped to calm racial tensions in Wilmington during his tenure as mayor in the early 1970s. Jews have also served as mayors of Gastonia, Hendersonville, Lumberton, and Tarboro, and Whiteville. In Goldsboro, Gertrude Weil became a prominent social reformer and political activist, fighting for women's suffrage and other progressive causes.

Jews have played an active role in the state’s civic life since the earliest days of Jewish settlement. Jacob Henry of Beaufort was elected to the North Carolina House of Commons in 1808, when all office holders were required to take a Christian oath. When he was challenged by another member of the House, Henry delivered an impassioned speech defending religious liberty in America. Moved by his oratory (or convinced by a narrow legal argument) the legislature allowed Henry to take his rightful seat. North Carolina did not remove the Christian oath requirement until 1868. Once this impediment was removed, Jews were elected to office around the state. In Wilmington, Sol Fishblate was elected alderman in 1873 and mayor five years later. Fishblate was elected mayor once again in 1891 during a time of white supremacist backlash. With his fellow Democrats, Fishblate argued that whites should control the local government, and supported the violent riot that overturned “black rule” in the city in 1898. In the Civil Rights era, Mutt Evans helped to lead Durham toward peaceful integration during his twelve years as mayor. B.D. Schwartz helped to calm racial tensions in Wilmington during his tenure as mayor in the early 1970s. Jews have also served as mayors of Gastonia, Hendersonville, Lumberton, and Tarboro, and Whiteville. In Goldsboro, Gertrude Weil became a prominent social reformer and political activist, fighting for women's suffrage and other progressive causes.

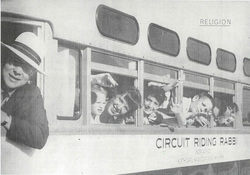

Rabbi Harold Friedman driving his bus outfitted to be a synagogue

Rabbi Harold Friedman driving his bus outfitted to be a synagogue

During the middle of the 20th century, Jews founded congregations in Salisbury (1944), Jacksonville (1955), Hickory (1950s) and Whiteville (1958). These and other small congregations in the state greatly benefitted from a novel circuit-riding rabbi program funded by Charlotte businessman I.D. Blumenthal. With a bus outfitted as a sanctuary, the rabbi would travel to small towns in North and South Carolina holding services. This program resulted in the Jews of Jacksonville, Hickory, and Whiteville forming congregations while helping revitalize the congregations in Statesville, Weldon, and Wilson.

Over the last several decades, the Jewish population of North Carolina has grown from around 10,000 people in 1960 to over 30,000 in 2011. Transplants from other parts of the country have been drawn to the thriving Research Triangle area as well as Charlotte. In Charlotte, the Jewish community created “Shalom Park,” a central campus housing two of the city’s synagogues, the Jewish Community Center, the Charlotte Jewish Day School, and the Charlotte Jewish Federation. Congregations in Durham, Raleigh, and Greensboro have also experienced significant growth in the last several decades. Also, a growing number of retirees have been drawn to the western part of the state, which offers natural beauty and mild climates. New congregations were founded in Boone (1974), Greenville (1977), Pinehurst (1999), Brevard (2001), Concord (2003), and Lake Norman (2006). Meanwhile, older congregations in Hendersonville, Asheville, New Bern, and Wilmington have been revitalized by this influx of newcomers. In Boone, a mix of retirees, faculty at Appalachian State University, and other Jewish locals decided to build the town’s first synagogue in 2009.

This growth has not benefitted all of North Carolina’s Jewish communities. In recent decades, congregations have closed in Goldsboro, Lumberton, Weldon, and Wilson as their Jewish populations have shrunk. With this decline in some smaller communities and growth in several others, North Carolina encompasses all of the demographic trends reshaping southern Jewish life in the 21st century.

For further reading, see Leonard Rogoff, Down Home: Jewish Life in North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010).

Over the last several decades, the Jewish population of North Carolina has grown from around 10,000 people in 1960 to over 30,000 in 2011. Transplants from other parts of the country have been drawn to the thriving Research Triangle area as well as Charlotte. In Charlotte, the Jewish community created “Shalom Park,” a central campus housing two of the city’s synagogues, the Jewish Community Center, the Charlotte Jewish Day School, and the Charlotte Jewish Federation. Congregations in Durham, Raleigh, and Greensboro have also experienced significant growth in the last several decades. Also, a growing number of retirees have been drawn to the western part of the state, which offers natural beauty and mild climates. New congregations were founded in Boone (1974), Greenville (1977), Pinehurst (1999), Brevard (2001), Concord (2003), and Lake Norman (2006). Meanwhile, older congregations in Hendersonville, Asheville, New Bern, and Wilmington have been revitalized by this influx of newcomers. In Boone, a mix of retirees, faculty at Appalachian State University, and other Jewish locals decided to build the town’s first synagogue in 2009.

This growth has not benefitted all of North Carolina’s Jewish communities. In recent decades, congregations have closed in Goldsboro, Lumberton, Weldon, and Wilson as their Jewish populations have shrunk. With this decline in some smaller communities and growth in several others, North Carolina encompasses all of the demographic trends reshaping southern Jewish life in the 21st century.

For further reading, see Leonard Rogoff, Down Home: Jewish Life in North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010).