Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Tennessee

Stretching across the mid-South, Tennessee connects the cotton country of the Mississippi River Delta to the Smokey Mountains of the east. Historically, Tennessee has been divided into three regions, encompassing the western, central, and eastern portions of the state. Jewish Tennessee can be similarly divided, with Memphis, Nashville, and Knoxville /Chattanooga serving as Jewish centers in the state. Unlike in places like Mississippi, Louisiana, and Arkansas, Tennessee had relatively few lasting small Jewish communities, as most Jews were concentrated in these four cities.

The first known Jewish settler was David Hart, who lived in Memphis in 1838. Growing numbers of Jewish settlers in Tennessee arrived in the 1840s, coming up from New Orleans along the Mississippi River in the west, and down from Cincinnati and Louisville to the central and eastern portions of the state. According to one account, the first Jewish congregation was established in Bolivar in 1851, though it did not last very long. In 1854, Jews established congregations in Memphis and Nashville, which have remained the two largest Jewish communities in the state ever since. Jews also founded congregations in Knoxville (1864), Chattanooga (1866), Murfreesboro (1866), Brownsville (1867), Jackson (1885), Bristol (1904), Columbia (1910s), Clarksville (1929), Oak Ridge (1943), Tullahoma (1957) and Union City (1959).

Cotton was king in the western part of the state, as Memphis emerged as an economic center of the Mississippi Delta cotton trade in the late 19th century. Jewish merchants and their families were drawn to the growing metropolis, which survived a series of deadly disease outbreaks in the 1870s. Jews also settled in nearby smaller towns like Brownsville and Jackson, opening stores that catered to area farmers. Nashville developed as a commercial hub in the central part of the state though the railroad rather than the river was its primary lifeline. The Jewish communities of Nashville and Memphis grew up together: the first Jewish congregations in each city were chartered by the same act of the state legislature in 1854. Smaller communities, like Columbia, Clarksville, and Murfreesboro, briefly flourished outside of the capital city before getting folded into Nashville’s Jewish community.

The first known Jewish settler was David Hart, who lived in Memphis in 1838. Growing numbers of Jewish settlers in Tennessee arrived in the 1840s, coming up from New Orleans along the Mississippi River in the west, and down from Cincinnati and Louisville to the central and eastern portions of the state. According to one account, the first Jewish congregation was established in Bolivar in 1851, though it did not last very long. In 1854, Jews established congregations in Memphis and Nashville, which have remained the two largest Jewish communities in the state ever since. Jews also founded congregations in Knoxville (1864), Chattanooga (1866), Murfreesboro (1866), Brownsville (1867), Jackson (1885), Bristol (1904), Columbia (1910s), Clarksville (1929), Oak Ridge (1943), Tullahoma (1957) and Union City (1959).

Cotton was king in the western part of the state, as Memphis emerged as an economic center of the Mississippi Delta cotton trade in the late 19th century. Jewish merchants and their families were drawn to the growing metropolis, which survived a series of deadly disease outbreaks in the 1870s. Jews also settled in nearby smaller towns like Brownsville and Jackson, opening stores that catered to area farmers. Nashville developed as a commercial hub in the central part of the state though the railroad rather than the river was its primary lifeline. The Jewish communities of Nashville and Memphis grew up together: the first Jewish congregations in each city were chartered by the same act of the state legislature in 1854. Smaller communities, like Columbia, Clarksville, and Murfreesboro, briefly flourished outside of the capital city before getting folded into Nashville’s Jewish community.

In eastern Tennessee, large-scale plantation agriculture never developed as the landscape is dominated by the Smokey Mountains. In Chattanooga and Knoxville, Jews began to arrive in significant numbers after the Civil War. Knoxville was on the trading route for many Jewish peddlers traveling west from Baltimore. Several stayed in Knoxville to open retail stores, though the community remained relatively small well into the 20th century. Chattanooga became a major railroad hub between the South, Midwest, and the Eastern Seaboard and later grew into a regional manufacturing center in the early 20th century. The city’s economic prosperity attracted increasing numbers of Jews; by 1937, 3800 Jews lived in Chattanooga. By the turn of the twentieth century, Jews had also established an active community in Bristol, in the far northeast corner of the state.

Most of the early congregations in Tennessee were founded by Jewish immigrants from Germany and eventually embraced Reform Judaism. In larger cities like Memphis, Nashville, Knoxville, and Chattanooga, Eastern European Jewish immigrants established their own Orthodox congregations in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Orthodox Judaism especially flourished in Memphis, where Jewish immigrants settled into the Pinch neighborhood and established several small shuls. A few of these were able to make the transition to the Memphis suburbs, including Baron Hirsch Congregation, which still claims to be the largest Orthodox congregation in the country.

Although they have been a tiny percentage of the state’s population, Jews have played an important role in Tennessee’s economic and civic life. In Memphis, Abe Plough (above) amassed a fortune in the pharmaceutical business, and used it to support many worthwhile local projects. Perhaps most notably, Plough secretly donated money to the city to cover the cost of raises for its sanitation workers to help settle their divisive strike in 1968. In Chattanooga, the Siskin family started a hugely successful steel and scrap metal business. After recovering from a near fatal train accident, Garrison Siskin pledged to devote his substantial resources to helping others. He and his brother Mose established the Siskin Memorial Foundation in 1950, supporting a variety of local causes. In 1990, the foundation provided funding for Chattanooga’s Siskin Hospital for Physical Rehabilitation. In Knoxville, Max Arnstein opened a dry goods store that grew into one of the city’s largest department stores. His philanthropy benefited the entire city, but his impact was especially felt by the Jewish community. The Arnstein family was the major donor behind Knoxville’s Jewish Community Center and two synagogues for Temple Beth El. In Nashville, Lee Loventhal was extremely active in civic causes, serving on the city park commission for 25 years and well as on the boards of Vanderbilt and Fisk Universities. In 1925, he helped to found the Community Chest, serving as its first president. Loventhal was also a leader of the Jewish community, helping to organize the local Young Men’s Hebrew Association. Mel Sturm served as Mayor of Jellico, outside of Knoxville, for a two year term 1954-55 at the young age of 29. Prior to that, he had a two year term on City Council as the Commissioner of Finance.

Most of the early congregations in Tennessee were founded by Jewish immigrants from Germany and eventually embraced Reform Judaism. In larger cities like Memphis, Nashville, Knoxville, and Chattanooga, Eastern European Jewish immigrants established their own Orthodox congregations in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Orthodox Judaism especially flourished in Memphis, where Jewish immigrants settled into the Pinch neighborhood and established several small shuls. A few of these were able to make the transition to the Memphis suburbs, including Baron Hirsch Congregation, which still claims to be the largest Orthodox congregation in the country.

Although they have been a tiny percentage of the state’s population, Jews have played an important role in Tennessee’s economic and civic life. In Memphis, Abe Plough (above) amassed a fortune in the pharmaceutical business, and used it to support many worthwhile local projects. Perhaps most notably, Plough secretly donated money to the city to cover the cost of raises for its sanitation workers to help settle their divisive strike in 1968. In Chattanooga, the Siskin family started a hugely successful steel and scrap metal business. After recovering from a near fatal train accident, Garrison Siskin pledged to devote his substantial resources to helping others. He and his brother Mose established the Siskin Memorial Foundation in 1950, supporting a variety of local causes. In 1990, the foundation provided funding for Chattanooga’s Siskin Hospital for Physical Rehabilitation. In Knoxville, Max Arnstein opened a dry goods store that grew into one of the city’s largest department stores. His philanthropy benefited the entire city, but his impact was especially felt by the Jewish community. The Arnstein family was the major donor behind Knoxville’s Jewish Community Center and two synagogues for Temple Beth El. In Nashville, Lee Loventhal was extremely active in civic causes, serving on the city park commission for 25 years and well as on the boards of Vanderbilt and Fisk Universities. In 1925, he helped to found the Community Chest, serving as its first president. Loventhal was also a leader of the Jewish community, helping to organize the local Young Men’s Hebrew Association. Mel Sturm served as Mayor of Jellico, outside of Knoxville, for a two year term 1954-55 at the young age of 29. Prior to that, he had a two year term on City Council as the Commissioner of Finance.

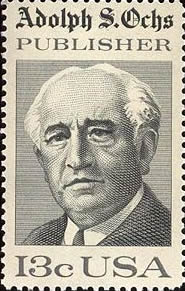

Tennessee Jews have left their stamp on the country. Adolph Ochs started as a newsboy for the Knoxville Chronicle. When he was only nineteen, he bought a controlling share of the struggling Chattanooga Times, which he built into a successful operation. In 1896, he purchased the New York Times, and transformed the second-rate gazette into the “paper of record.” Abe Fortas grew up in Memphis before moving to Washington to work in the New Deal administration of Franklin Roosevelt. He later became a prominent lawyer, successfully arguing the landmark Supreme Court case, Gideon v. Wainwright. Lyndon Johnson appointed him to the Supreme Court in 1965, though Fortas resigned in 1969 after ethical questions were raised about his financial dealings. Born in Winchester, Tennessee, Dinah Shore moved to Nashville as a young girl. After graduating from Vanderbilt, Shore moved to New York and won fame as a singer, later becoming one of the early stars of television.

Historically, Tennessee’s Jewish population has been centered in the four largest cities. In 1937, over 95% of the state’s Jewish population lived in Memphis, Nashville, Chattanooga, or Knoxville, as compared to only 25% of all Tennesseans. Memphis has long been the state’s largest Jewish community, reaching a peak of 13,350 Jews in 1937, before shrinking to about 9,000 Jews by the 1960s. The city’s Jewish population has continued to decline slowly. In 2006, an estimated 7,800 Jews lived in Memphis. Chattanooga has also seen a decline in its Jewish community, from a peak of 3,800 in 1937 to only 1,450 in 1997. In contrast, Nashville and Knoxville have grown. Nashville had 4,200 Jews in 1937 and 7,800 in 2002. Knoxville grew from 800 Jews in 1960 to 1,800 in 1997.

The emergence of Nashville as the largest Jewish community in the state and Knoxville’s growth reflect the general demographic trend in the Jewish South. Southern Jewish life has flourished in the booming areas of the sunbelt and declined in the regions that had been reliant on farming. Previously, Tennessee Jews were concentrated in retail trade, often tied to the local farm economy. But with structural changes in both agriculture and the retail industry, the fabled “Jew Store” has been largely supplanted by the Jewish doctor, lawyer, and corporate executive. Nashville has become a corporate and professional center of the South, and Jews from around the country continue to move there. Knoxville, with its growing state university and the nearby research labs in Oak Ridge, has similarly attracted academics, medical professionals, and scientists. Meanwhile, Jewish communities in Jackson, Brownsville, Union City, Clarksville, and Tullahoma have either withered or disappeared.

In recent decades, Tennessee’s Jewish communities have been witness to both the growth and decline of the Jewish South. In 1927, 22,500 Jews lived in the state; by 1960, this number had declined to 16,800. In recent decades, the state’s Jewish population has grown, reaching over 19,000 by 2006. The large majority of this Jewish population, over 80%, is centered in Memphis and Nashville. In Tennessee’s Jewish history, the big cities have been paramount, and region-wide demographic trends show no sign of this changing.

Historically, Tennessee’s Jewish population has been centered in the four largest cities. In 1937, over 95% of the state’s Jewish population lived in Memphis, Nashville, Chattanooga, or Knoxville, as compared to only 25% of all Tennesseans. Memphis has long been the state’s largest Jewish community, reaching a peak of 13,350 Jews in 1937, before shrinking to about 9,000 Jews by the 1960s. The city’s Jewish population has continued to decline slowly. In 2006, an estimated 7,800 Jews lived in Memphis. Chattanooga has also seen a decline in its Jewish community, from a peak of 3,800 in 1937 to only 1,450 in 1997. In contrast, Nashville and Knoxville have grown. Nashville had 4,200 Jews in 1937 and 7,800 in 2002. Knoxville grew from 800 Jews in 1960 to 1,800 in 1997.

The emergence of Nashville as the largest Jewish community in the state and Knoxville’s growth reflect the general demographic trend in the Jewish South. Southern Jewish life has flourished in the booming areas of the sunbelt and declined in the regions that had been reliant on farming. Previously, Tennessee Jews were concentrated in retail trade, often tied to the local farm economy. But with structural changes in both agriculture and the retail industry, the fabled “Jew Store” has been largely supplanted by the Jewish doctor, lawyer, and corporate executive. Nashville has become a corporate and professional center of the South, and Jews from around the country continue to move there. Knoxville, with its growing state university and the nearby research labs in Oak Ridge, has similarly attracted academics, medical professionals, and scientists. Meanwhile, Jewish communities in Jackson, Brownsville, Union City, Clarksville, and Tullahoma have either withered or disappeared.

In recent decades, Tennessee’s Jewish communities have been witness to both the growth and decline of the Jewish South. In 1927, 22,500 Jews lived in the state; by 1960, this number had declined to 16,800. In recent decades, the state’s Jewish population has grown, reaching over 19,000 by 2006. The large majority of this Jewish population, over 80%, is centered in Memphis and Nashville. In Tennessee’s Jewish history, the big cities have been paramount, and region-wide demographic trends show no sign of this changing.

|

©2024 Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life

|