Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Nashville, Tennessee

Nashville: Historical Overview

|

Nicknamed “Music City USA,” Nashville is best known as the home of the country music industry. Countless aspiring singers, writers, and musicians head to Nashville looking for fame and fortune. But Nashville was a center for fortune seekers long before the traditional songs of Southern and Appalachian musicians began to be pressed onto shellac and vinyl. Beginning in the mid-19th century, growing numbers of Jews from Europe came to Tennessee’s capital city in search of a better life. There they found opportunity and established a community that continues to thrive today.

|

Stories of the Jewish Community in Nashville

Early Settlers

Although Nashville was founded in 1780, it did not attract a significant Jewish presence until the 1840s. A few Jews had lived temporarily in the town that had been originally called Fort Nashborough. In 1795, Benjamin and Hannah Myers lived in the growing trading post on the Cumberland River, where Hannah gave birth to their daughter Sarah. Members of New York’s Shearith Israel congregation, the Myers did not stay in Tennessee long, moving to Virginia by the following year. It would be over 40 years before anything like a Jewish community would take root in Nashville.

By the 1840s, Jewish immigrants from the German states and Poland began to settle in Tennessee’s capital city. During the 1850s, many Jews came and went from Nashville; 160 Jewish household heads lived in Nashville at some point in the decade, although the Jewish population was never that high at any one time. In 1851, there were 28 Jewish families in Nashville, but only 12 of them were still in Nashville ten years later. Of the 105 Jewish families listed in the 1860 census as living in Nashville, only 44 still lived there in 1870. This high rate of population turnover was typical for the time, when Jewish immigrants moved around the country looking for economic opportunity. This mobility was facilitated when the railroad was built through town in the 1850s, linking Nashville to other cities around the country.

Although Nashville was founded in 1780, it did not attract a significant Jewish presence until the 1840s. A few Jews had lived temporarily in the town that had been originally called Fort Nashborough. In 1795, Benjamin and Hannah Myers lived in the growing trading post on the Cumberland River, where Hannah gave birth to their daughter Sarah. Members of New York’s Shearith Israel congregation, the Myers did not stay in Tennessee long, moving to Virginia by the following year. It would be over 40 years before anything like a Jewish community would take root in Nashville.

By the 1840s, Jewish immigrants from the German states and Poland began to settle in Tennessee’s capital city. During the 1850s, many Jews came and went from Nashville; 160 Jewish household heads lived in Nashville at some point in the decade, although the Jewish population was never that high at any one time. In 1851, there were 28 Jewish families in Nashville, but only 12 of them were still in Nashville ten years later. Of the 105 Jewish families listed in the 1860 census as living in Nashville, only 44 still lived there in 1870. This high rate of population turnover was typical for the time, when Jewish immigrants moved around the country looking for economic opportunity. This mobility was facilitated when the railroad was built through town in the 1850s, linking Nashville to other cities around the country.

Organized Jewish Life in Nashville

Despite this high turnover, Nashville Jews managed to establish community institutions. In 1848, they first formed a minyan, meeting in the home of Isaac Garritson. Three years later, they organized the Hebrew Benevolent Burial Association and purchased land for a cemetery. This small group of Jews contacted Rabbi Isaac Leeser of Philadelphia requesting prayer books for their growing minyan. In 1854, they officially incorporated as “Kahl Kodesh Mogen David” (Holy Community of the Shield of David); some have suggested that they chose the name in honor of Davidson County.

The early history of Jewish religious life in Nashville is rife with turmoil and division. In 1859, a group of dissatisfied members of Mogen David left to form their own congregation, Ohava Emes (Lovers of Truth). Five years later, another group split from Mogen David and formed the city’s first Reform congregation, B’nai Yeshurun (Sons of Righteousness). This small Jewish community now had three tiny congregations and not one permanent synagogue. Nashville gained the reputation as a particularly divisive community, receiving a rebuke from Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise of Cincinnati, who blamed “the unfortunate spirit of quarrel and small ambition” for the factionalism.

Despite these quarrels over religion, Nashville Jews did manage to establish organizations that united them in caring for those in need. In 1859, they founded the Young Men’s Hebrew Benevolent Society; a few years later, women organized the Ladies’ Hebrew Benevolent Society. In 1863, Jewish men founded a local chapter of B’nai B’rith, whose philosophy of bridging religious differences was much needed in Nashville.

In 1860, the Nashville Jewish community was largely young and foreign-born. Of the 99 Jewish household heads in Nashville, the average age was 32; most all of them were immigrants from either the German states or Poland. Most were of relatively modest economic means. Almost a quarter of them were peddlers. A large majority were business owners, with many owning small dry goods, clothing, or grocery stores.

Despite this high turnover, Nashville Jews managed to establish community institutions. In 1848, they first formed a minyan, meeting in the home of Isaac Garritson. Three years later, they organized the Hebrew Benevolent Burial Association and purchased land for a cemetery. This small group of Jews contacted Rabbi Isaac Leeser of Philadelphia requesting prayer books for their growing minyan. In 1854, they officially incorporated as “Kahl Kodesh Mogen David” (Holy Community of the Shield of David); some have suggested that they chose the name in honor of Davidson County.

The early history of Jewish religious life in Nashville is rife with turmoil and division. In 1859, a group of dissatisfied members of Mogen David left to form their own congregation, Ohava Emes (Lovers of Truth). Five years later, another group split from Mogen David and formed the city’s first Reform congregation, B’nai Yeshurun (Sons of Righteousness). This small Jewish community now had three tiny congregations and not one permanent synagogue. Nashville gained the reputation as a particularly divisive community, receiving a rebuke from Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise of Cincinnati, who blamed “the unfortunate spirit of quarrel and small ambition” for the factionalism.

Despite these quarrels over religion, Nashville Jews did manage to establish organizations that united them in caring for those in need. In 1859, they founded the Young Men’s Hebrew Benevolent Society; a few years later, women organized the Ladies’ Hebrew Benevolent Society. In 1863, Jewish men founded a local chapter of B’nai B’rith, whose philosophy of bridging religious differences was much needed in Nashville.

In 1860, the Nashville Jewish community was largely young and foreign-born. Of the 99 Jewish household heads in Nashville, the average age was 32; most all of them were immigrants from either the German states or Poland. Most were of relatively modest economic means. Almost a quarter of them were peddlers. A large majority were business owners, with many owning small dry goods, clothing, or grocery stores.

The Civil War and Reconstruction

During the Civil War, many Nashville Jews were strong supporters of the Confederacy, although only a small minority owned slaves on the eve of secession. Of the 105 Jewish households in Nashville in 1860, only seven contained slaves; each of these Jewish slaveholders owned one slave. Rabbi Samuel Raphael of Congregation Mogen David used biblical passages to defend the peculiar institution in a letter printed in the local newspaper. Ohava Emes passed a resolution in 1861 praising the Confederacy and calling on its members to help the Southern cause. The congregation and the local Jewish relief societies raised money for sick Confederate soldiers stationed in the city.

The Union army was quickly able to capture Nashville, occupying it by February of 1862. Some Nashville Jews chafed under Northern control and the accompanying restrictions on trade. Jacob Bloomstein, a prominent local merchant, was accused of spying and smuggling goods to the Confederacy, and was sent to a military prison in Illinois. Held without a trial, he was finally released after his wife sent an appeal to military governor Andrew Johnson. Despite their support for the Confederacy, Nashville Jews mourned the death of Abraham Lincoln, with the local B’nai B’rith lodge draping its meeting hall in mourning for thirty days and local congregations holding special memorial services.

Nashville Jews maintained their antipathy to General Ulysses S. Grant, whose notorious wartime Order No. 11 decreed that all Jews leave the military district. Although it was soon rescinded by President Lincoln, Jews in Nashville were outraged when Grant ran for president in 1868. They organized a protest meeting, during which one speaker likened the candidate to Haman, the notorious anti-Semite from the Purim story. They issued proclamations against Grant which ran in the local newspaper and organized an Anti-Grant club that had officers and various committees. Several Jewish immigrants in Nashville became naturalized citizens just so they could vote against Grant in the 1868 election. While these efforts to defeat the Civil War hero were unsuccessful, they do show that these Jewish immigrants were not afraid to speak out on political issues as Jews. A few years later, Jews helped to organize a protest against General W.G. Harding, after he had made a local speech decrying immigrants. Nashville Jews also successfully lobbied the state legislature to allow rabbis to give the opening prayer before sessions.

Area Jews were sometimes caught up in the turmoil of the Reconstruction Era. The Ku Klux Klan, which emerged in the aftermath of the Civil War to try to reassert white supremacy, occasionally targeted Jews. In 1868, the Klan murdered a Jewish merchant, S.A. Bierfeld, in nearby Franklin along with his black employee Lawrence Bowman. At the time, other Franklin Jews asserted that Bierfeld’s murder had more to do with his radical Republican politics than his religion. In another incident, a Jewish peddler named Joseph Lowenheim was threatened by hooded men armed with knives; after Lowenheim proved that he was a Mason, the gang set him free.

Lowenheim’s membership in the Masons was not unusual, as Nashville Jews became active in the local economy and community. In the mid-19th century, Nashville developed into a regional trading center. By 1860, it had 12 large wholesale firms that served stores in Tennessee, Alabama, and Kentucky, though none of these firms were Jewish-owned. At the time, Jews owned smaller retail stores in Nashville. By 1847, Louis Powers owned a clothing store. In 1860, both Louis and his older brother Michael owned clothing stores in Nashville. Jews also owned grocery stores, bakeries, liquor and tobacco stores, and a kosher boarding house, which catered to Jewish peddlers passing through town. The four Lyons brothers owned a tobacco and liquor store; Lyons and Company also made their own cigars. Showing that the path to economic success was not easy, their business suffered during the Panic of 1857. By 1859, only one of the brothers remained in the tobacco business. Ben Lyon opened a billiard hall and saloon. On the eve of the Civil War, three Nashville Jews had fortunes of over $10,000; most were small businessmen.

During the Civil War, many Nashville Jews were strong supporters of the Confederacy, although only a small minority owned slaves on the eve of secession. Of the 105 Jewish households in Nashville in 1860, only seven contained slaves; each of these Jewish slaveholders owned one slave. Rabbi Samuel Raphael of Congregation Mogen David used biblical passages to defend the peculiar institution in a letter printed in the local newspaper. Ohava Emes passed a resolution in 1861 praising the Confederacy and calling on its members to help the Southern cause. The congregation and the local Jewish relief societies raised money for sick Confederate soldiers stationed in the city.

The Union army was quickly able to capture Nashville, occupying it by February of 1862. Some Nashville Jews chafed under Northern control and the accompanying restrictions on trade. Jacob Bloomstein, a prominent local merchant, was accused of spying and smuggling goods to the Confederacy, and was sent to a military prison in Illinois. Held without a trial, he was finally released after his wife sent an appeal to military governor Andrew Johnson. Despite their support for the Confederacy, Nashville Jews mourned the death of Abraham Lincoln, with the local B’nai B’rith lodge draping its meeting hall in mourning for thirty days and local congregations holding special memorial services.

Nashville Jews maintained their antipathy to General Ulysses S. Grant, whose notorious wartime Order No. 11 decreed that all Jews leave the military district. Although it was soon rescinded by President Lincoln, Jews in Nashville were outraged when Grant ran for president in 1868. They organized a protest meeting, during which one speaker likened the candidate to Haman, the notorious anti-Semite from the Purim story. They issued proclamations against Grant which ran in the local newspaper and organized an Anti-Grant club that had officers and various committees. Several Jewish immigrants in Nashville became naturalized citizens just so they could vote against Grant in the 1868 election. While these efforts to defeat the Civil War hero were unsuccessful, they do show that these Jewish immigrants were not afraid to speak out on political issues as Jews. A few years later, Jews helped to organize a protest against General W.G. Harding, after he had made a local speech decrying immigrants. Nashville Jews also successfully lobbied the state legislature to allow rabbis to give the opening prayer before sessions.

Area Jews were sometimes caught up in the turmoil of the Reconstruction Era. The Ku Klux Klan, which emerged in the aftermath of the Civil War to try to reassert white supremacy, occasionally targeted Jews. In 1868, the Klan murdered a Jewish merchant, S.A. Bierfeld, in nearby Franklin along with his black employee Lawrence Bowman. At the time, other Franklin Jews asserted that Bierfeld’s murder had more to do with his radical Republican politics than his religion. In another incident, a Jewish peddler named Joseph Lowenheim was threatened by hooded men armed with knives; after Lowenheim proved that he was a Mason, the gang set him free.

Lowenheim’s membership in the Masons was not unusual, as Nashville Jews became active in the local economy and community. In the mid-19th century, Nashville developed into a regional trading center. By 1860, it had 12 large wholesale firms that served stores in Tennessee, Alabama, and Kentucky, though none of these firms were Jewish-owned. At the time, Jews owned smaller retail stores in Nashville. By 1847, Louis Powers owned a clothing store. In 1860, both Louis and his older brother Michael owned clothing stores in Nashville. Jews also owned grocery stores, bakeries, liquor and tobacco stores, and a kosher boarding house, which catered to Jewish peddlers passing through town. The four Lyons brothers owned a tobacco and liquor store; Lyons and Company also made their own cigars. Showing that the path to economic success was not easy, their business suffered during the Panic of 1857. By 1859, only one of the brothers remained in the tobacco business. Ben Lyon opened a billiard hall and saloon. On the eve of the Civil War, three Nashville Jews had fortunes of over $10,000; most were small businessmen.

Jewish Businesses in Nashville

After the Civil War, the Jewish population in Nashville flourished as Jews became more economically established. In 1867, the Fourth National Bank of Nashville was founded by 52 men, four of whom were Jews. Julius and Max Sax, two Jewish immigrants from Prussia, founded the Nashville Savings Bank in 1863, which remained in business for three decades before failing in the Panic of 1893. In the late 19th century, the Sax brothers became leading citizens in Nashville, serving on the local reception committee when President Grover Cleveland visited the city. They were also active in the Jewish community, with Max serving as president of the local B’nai B’rith Chapter and the Vine Street Temple. His wife Hannah was the first president of the Vine Street Temple’s Ladies Auxiliary and served on the board of the Women’s Mission Home, which helped working women. After their bank failed, the family moved to New York.

Morris Loveman endured a series of misfortunes before setting down roots in Nashville. Born in Hungary, Loveman came over with his family to New York City in 1854. During the voyage, his infant child died. He initially settled in Owosso, Michigan, where his older brother already lived. Starting as a peddler, Morris moved into various other failing ventures. His bakery was unsuccessful and he closed his firecracker manufacturing business after a mishap cost him sight in one of his eyes and hearing in one of his ears. In 1860, the family moved to Mount Pleasant, Tennessee, where they opened a dry goods store. Once the war broke out, they sought the relative safety of the city by moving to Nashville. Morris opened a wholesale dry goods business which supplied many Jewish peddlers in the area. His son, David Loveman, opened a dress manufacturing business which became known for its popular line of hoop skirts in the 1860s. He later opened a dry goods store, D. Loveman’s, which grew into a successful department store and Nashville institution. Morris’ other son, Adolph, founded the A.M. Loveman Lumber and Box Company, which is still in business today.

Nathan Cline came to the United States from Poland in 1851. By 1857, he was living in Nashville and owned a liquor business. During the Civil War, he opened a junk business with Louis Bernheim, a German Jewish immigrant who had settled in Nashville. The partners built the Cline-Bernheim Company into a successful scrap iron business that flourished for over a century. When Cline’s son Sol married Bernheim’s daughter Tillie, the families’ partnership was further solidified.

Young brothers Louis and George Rosenheim came to Nashville from Warsaw at the urging of their aunt, Betty Lusky, who already lived there. They opened a candy store which failed during the cholera epidemic of 1873. They later opened a dry goods store downtown with $240 they had saved. By 1890, their store had grown to become the largest department store in the city, with 100 employees and a five-story building that occupied an entire city block. The business suffered during the economic hardships of the 1890s. By 1899, the partnership had dissolved, and George left Nashville. Louis stayed and opened a women’s hat store, which he ran until he died in 1924. Louis was a leader of the local business community, serving on several bank boards and investing in a streetcar line and various real estate ventures.

After the Civil War, the Jewish population in Nashville flourished as Jews became more economically established. In 1867, the Fourth National Bank of Nashville was founded by 52 men, four of whom were Jews. Julius and Max Sax, two Jewish immigrants from Prussia, founded the Nashville Savings Bank in 1863, which remained in business for three decades before failing in the Panic of 1893. In the late 19th century, the Sax brothers became leading citizens in Nashville, serving on the local reception committee when President Grover Cleveland visited the city. They were also active in the Jewish community, with Max serving as president of the local B’nai B’rith Chapter and the Vine Street Temple. His wife Hannah was the first president of the Vine Street Temple’s Ladies Auxiliary and served on the board of the Women’s Mission Home, which helped working women. After their bank failed, the family moved to New York.

Morris Loveman endured a series of misfortunes before setting down roots in Nashville. Born in Hungary, Loveman came over with his family to New York City in 1854. During the voyage, his infant child died. He initially settled in Owosso, Michigan, where his older brother already lived. Starting as a peddler, Morris moved into various other failing ventures. His bakery was unsuccessful and he closed his firecracker manufacturing business after a mishap cost him sight in one of his eyes and hearing in one of his ears. In 1860, the family moved to Mount Pleasant, Tennessee, where they opened a dry goods store. Once the war broke out, they sought the relative safety of the city by moving to Nashville. Morris opened a wholesale dry goods business which supplied many Jewish peddlers in the area. His son, David Loveman, opened a dress manufacturing business which became known for its popular line of hoop skirts in the 1860s. He later opened a dry goods store, D. Loveman’s, which grew into a successful department store and Nashville institution. Morris’ other son, Adolph, founded the A.M. Loveman Lumber and Box Company, which is still in business today.

Nathan Cline came to the United States from Poland in 1851. By 1857, he was living in Nashville and owned a liquor business. During the Civil War, he opened a junk business with Louis Bernheim, a German Jewish immigrant who had settled in Nashville. The partners built the Cline-Bernheim Company into a successful scrap iron business that flourished for over a century. When Cline’s son Sol married Bernheim’s daughter Tillie, the families’ partnership was further solidified.

Young brothers Louis and George Rosenheim came to Nashville from Warsaw at the urging of their aunt, Betty Lusky, who already lived there. They opened a candy store which failed during the cholera epidemic of 1873. They later opened a dry goods store downtown with $240 they had saved. By 1890, their store had grown to become the largest department store in the city, with 100 employees and a five-story building that occupied an entire city block. The business suffered during the economic hardships of the 1890s. By 1899, the partnership had dissolved, and George left Nashville. Louis stayed and opened a women’s hat store, which he ran until he died in 1924. Louis was a leader of the local business community, serving on several bank boards and investing in a streetcar line and various real estate ventures.

Early Civic Engagement

Jews were very active in civic life in Nashville. Many were involved with non-Jewish fraternal societies like the Masons and Odd Fellows. A number joined German-speaking lodges, reflecting their strong German identity. Indeed, most of the sermons delivered in Nashville’s synagogues in the latter half of the 19th century were in German. Despite their status as immigrants, several Jews became involved in local government. The Bavarian-born Benjamin Herman owned a wholesale supply business and spent two terms on the Nashville school board. He also served on the boards of the Masonic Widows and Orphans Home and the Nashville Chamber of Commerce. Benjamin Lindauer served on the city council and was elected council president in 1899. Jacob Levine was a magistrate of the county court for several decades until his death in 1934.

Many Nashville Jews were involved with both the Jewish and the larger community. Lee Loventhal was born in Nashville and took over the insurance business started by his father. Loventhal was extremely active in civic causes in his hometown, serving on the city park commission for 25 years and well as on the boards of Vanderbilt and Fisk Universities. He helped to raise $2 million for the war effort during World War I. In 1925, he helped to found the Community Chest, serving as its first president. Loventhal was also a leader of the Jewish community, helping to found the local Young Men’s Hebrew Association. Loventhal also served on the boards of the Levi Hospital in Hot Springs, Arkansas, the Jewish Old Age Home in Memphis, and Hebrew Union College.

Jews were very active in civic life in Nashville. Many were involved with non-Jewish fraternal societies like the Masons and Odd Fellows. A number joined German-speaking lodges, reflecting their strong German identity. Indeed, most of the sermons delivered in Nashville’s synagogues in the latter half of the 19th century were in German. Despite their status as immigrants, several Jews became involved in local government. The Bavarian-born Benjamin Herman owned a wholesale supply business and spent two terms on the Nashville school board. He also served on the boards of the Masonic Widows and Orphans Home and the Nashville Chamber of Commerce. Benjamin Lindauer served on the city council and was elected council president in 1899. Jacob Levine was a magistrate of the county court for several decades until his death in 1934.

Many Nashville Jews were involved with both the Jewish and the larger community. Lee Loventhal was born in Nashville and took over the insurance business started by his father. Loventhal was extremely active in civic causes in his hometown, serving on the city park commission for 25 years and well as on the boards of Vanderbilt and Fisk Universities. He helped to raise $2 million for the war effort during World War I. In 1925, he helped to found the Community Chest, serving as its first president. Loventhal was also a leader of the Jewish community, helping to found the local Young Men’s Hebrew Association. Loventhal also served on the boards of the Levi Hospital in Hot Springs, Arkansas, the Jewish Old Age Home in Memphis, and Hebrew Union College.

The Community Grows

Nashville’s Jewish population grew significantly in the late 19th century. In 1860, 325 Jews lived in Nashville; by 1870, 875 did. By the turn of the century, 1,900 Jews lived in Nashville. Most of these, 62%, were born in the United States. Seventy percent of the Jewish immigrants living in Nashville in 1900 had come in the previous 20 years, the era of the Eastern European wave of Jewish immigration. Almost 60% of foreign-born Jews in Nashville emigrated from Russia or Hungary. In 1871, a small group of Hungarian Jews founded the Hungarian Benevolent Society, and held their own High Holiday services at the Masonic Temple. Hungarian Jews later founded their own Orthodox congregation, Sherith Israel (Remnant of Israel), in 1904.

The Nashville Section of the National Council of Jewish Women was founded in 1901 and soon sought to help this growing immigrant population. They began to offer classes on America for newly arriving Jewish immigrants to “teach and implant the fundamentals of true Americanism.” In 1909, they opened the Bertha Fensterwald Settlement House, named for their first president. It became the Bertha Fensterwald Social Center in 1916 and offered English classes as well as health services and social programs for new immigrants to help them assimilate to life in America.

Jews joined several other local Jewish organizations. In the 1870s, Nashville Jews formed the socially oriented Concordia Club. In 1882, it was renamed the Standard Club and served the economic elite of the Nashville Jewish community. In addition to three congregations, in 1907 Nashville Jews also belonged to the Free Sons of Israel, the B’nai B’rith, the Jewish Chautauqua Society, and the Knights of Joseph. Later, there were local Zionist organizations, including Hadassah, and a chapter of the socialist Workmen’s Circle.

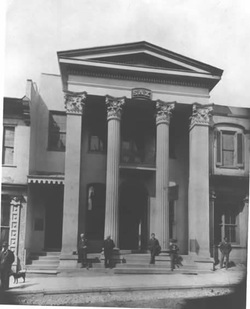

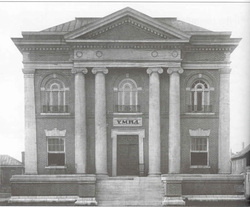

With all of these disparate social, religious, and political organizations, some Nashville Jews saw the need for one institution that could unite the entire Jewish community. In 1902, a group of Jews founded the Young Men’s Hebrew Association, with its mission to improve “the mental, moral, and physical condition of its members” and to advance “knowledge of Jewish history and religion.” They initially met in rented rooms above a restaurant, but soon outgrew the space and bought land for a permanent building. In 1907, with a membership of 200, they laid the cornerstone in a ceremony that drew the mayor of Nashville and the governor of Tennessee. Dedicated in 1908, the YMHA had a gym, game room, library, and swimming pool. Women were allowed to use the facilities, as the YMHA became an important center of Jewish life in Nashville. In 1924, they built a new four-story brick facility, which they shared with the Young Women’s Hebrew Association.

In 1948, the two groups merged to create the Jewish Community Center and later built a new facility in the West End of Nashville, where most Jews lived at the time. In 1984, the JCC moved once again, to its current site on Percy Warner Boulevard, which offered more space for outdoor activities and parking. The center offered social, educational, and cultural programs for the entire Nashville Jewish community, which sometimes led to dissension. One divisive point was whether to open the JCC on Saturdays. After 20 years of conflict and debate, in 1989, the center decided to be open for limited activities on the Jewish Sabbath. Those who were opposed to this decision were allowed to pay a slightly lower membership rate so they wouldn’t be subsidizing its Saturday activities. Through such compromises, the JCC has continued to be a home for Nashville Jews regardless of their religious affiliation.

Nashville’s Jewish population grew significantly in the late 19th century. In 1860, 325 Jews lived in Nashville; by 1870, 875 did. By the turn of the century, 1,900 Jews lived in Nashville. Most of these, 62%, were born in the United States. Seventy percent of the Jewish immigrants living in Nashville in 1900 had come in the previous 20 years, the era of the Eastern European wave of Jewish immigration. Almost 60% of foreign-born Jews in Nashville emigrated from Russia or Hungary. In 1871, a small group of Hungarian Jews founded the Hungarian Benevolent Society, and held their own High Holiday services at the Masonic Temple. Hungarian Jews later founded their own Orthodox congregation, Sherith Israel (Remnant of Israel), in 1904.

The Nashville Section of the National Council of Jewish Women was founded in 1901 and soon sought to help this growing immigrant population. They began to offer classes on America for newly arriving Jewish immigrants to “teach and implant the fundamentals of true Americanism.” In 1909, they opened the Bertha Fensterwald Settlement House, named for their first president. It became the Bertha Fensterwald Social Center in 1916 and offered English classes as well as health services and social programs for new immigrants to help them assimilate to life in America.

Jews joined several other local Jewish organizations. In the 1870s, Nashville Jews formed the socially oriented Concordia Club. In 1882, it was renamed the Standard Club and served the economic elite of the Nashville Jewish community. In addition to three congregations, in 1907 Nashville Jews also belonged to the Free Sons of Israel, the B’nai B’rith, the Jewish Chautauqua Society, and the Knights of Joseph. Later, there were local Zionist organizations, including Hadassah, and a chapter of the socialist Workmen’s Circle.

With all of these disparate social, religious, and political organizations, some Nashville Jews saw the need for one institution that could unite the entire Jewish community. In 1902, a group of Jews founded the Young Men’s Hebrew Association, with its mission to improve “the mental, moral, and physical condition of its members” and to advance “knowledge of Jewish history and religion.” They initially met in rented rooms above a restaurant, but soon outgrew the space and bought land for a permanent building. In 1907, with a membership of 200, they laid the cornerstone in a ceremony that drew the mayor of Nashville and the governor of Tennessee. Dedicated in 1908, the YMHA had a gym, game room, library, and swimming pool. Women were allowed to use the facilities, as the YMHA became an important center of Jewish life in Nashville. In 1924, they built a new four-story brick facility, which they shared with the Young Women’s Hebrew Association.

In 1948, the two groups merged to create the Jewish Community Center and later built a new facility in the West End of Nashville, where most Jews lived at the time. In 1984, the JCC moved once again, to its current site on Percy Warner Boulevard, which offered more space for outdoor activities and parking. The center offered social, educational, and cultural programs for the entire Nashville Jewish community, which sometimes led to dissension. One divisive point was whether to open the JCC on Saturdays. After 20 years of conflict and debate, in 1989, the center decided to be open for limited activities on the Jewish Sabbath. Those who were opposed to this decision were allowed to pay a slightly lower membership rate so they wouldn’t be subsidizing its Saturday activities. Through such compromises, the JCC has continued to be a home for Nashville Jews regardless of their religious affiliation.

Community Champions

Successful Nashville Jews gave back to their community, especially during World War II. Meier Werthan founded the Werthan Bag and Burlap Company in the 1890s.The business grew tremendously, and during World War II, Joe Werthan, Meier’s son, established the Joe Werthan Service Center, a 250-bed facility for servicemen who spent time in Nashville. Joe was appalled by the sight of young servicemen on leave sleeping outdoors in Nashville, so he created a facility where soldiers of any faith could sleep for free and find meals and recreation.

Jacob May came to the United States from Germany in 1879 at the age of 18. After starting out as a peddler in Nashville, May soon won a state contract for prison labor and founded the Rock City Hosiery Mills at the Tennessee State Penitentiary. In 1908, he founded the May Hosiery Mill in Nashville, which soon grew into a thriving business, supplying socks to some of the finest department stores in the country. Jacob watched with horror as the Nazis came to power in his homeland, and he spent much of the late 1930s working to bring Jewish refugees to the United States. The May family sponsored about 200 Jewish refugees and found them work in the United States. Jacob encouraged other Jews to do the same, and through his efforts, about 230 families escaped Europe before the Holocaust.

A number of Jewish women in Nashville played important roles in the larger community. Anne Garfinkle fought against bible readings in the Nashville public schools in 1912-13. She pressured the school board and wrote many letters to the editor of the local paper arguing her case. Though her efforts were unsuccessful, she was not afraid to take a controversial public stand on the issue. Garfinkle later became an active Zionist, serving as secretary of the B’nai Zion Society. Corinne Cohn was a longtime member of the Nashville Board of Education; Cohn High School was named in her honor in 1926. Pauline Tenzel emigrated from Romania in 1921. She attended the University of Arkansas Medical School, and became an obstetrician. She moved to Nashville in 1933, and set up a practice, becoming one of the first female ob/gyns in towns. She worked in Nashville until she retired in 1979. Annette Eskind was a casework supervisor for the Jewish Family Service for many years. She spent almost a decade on the local Board of Education and founded the Nashville Public Education Foundation. She and her husband, Irwin Eskind, endowed a biomedical library and a research chair in human development at the Vanderbilt University Medical School.

The most famous Jewish woman from Nashville was Fannye Rose Shore, who was born in Winchester, Tennessee, in 1917. She and her family moved to Nashville in 1923, and Fannye started singing on local radio while she was a student at Vanderbilt. When she graduated in 1938, she moved to New York to seek fortune and fame as Dinah Shore. After getting a break singing on the Eddie Cantor Radio Show, Dinah Shore became a star. She later hosted her own television talk show, which set the model for many of the daytime talk shows today.

Successful Nashville Jews gave back to their community, especially during World War II. Meier Werthan founded the Werthan Bag and Burlap Company in the 1890s.The business grew tremendously, and during World War II, Joe Werthan, Meier’s son, established the Joe Werthan Service Center, a 250-bed facility for servicemen who spent time in Nashville. Joe was appalled by the sight of young servicemen on leave sleeping outdoors in Nashville, so he created a facility where soldiers of any faith could sleep for free and find meals and recreation.

Jacob May came to the United States from Germany in 1879 at the age of 18. After starting out as a peddler in Nashville, May soon won a state contract for prison labor and founded the Rock City Hosiery Mills at the Tennessee State Penitentiary. In 1908, he founded the May Hosiery Mill in Nashville, which soon grew into a thriving business, supplying socks to some of the finest department stores in the country. Jacob watched with horror as the Nazis came to power in his homeland, and he spent much of the late 1930s working to bring Jewish refugees to the United States. The May family sponsored about 200 Jewish refugees and found them work in the United States. Jacob encouraged other Jews to do the same, and through his efforts, about 230 families escaped Europe before the Holocaust.

A number of Jewish women in Nashville played important roles in the larger community. Anne Garfinkle fought against bible readings in the Nashville public schools in 1912-13. She pressured the school board and wrote many letters to the editor of the local paper arguing her case. Though her efforts were unsuccessful, she was not afraid to take a controversial public stand on the issue. Garfinkle later became an active Zionist, serving as secretary of the B’nai Zion Society. Corinne Cohn was a longtime member of the Nashville Board of Education; Cohn High School was named in her honor in 1926. Pauline Tenzel emigrated from Romania in 1921. She attended the University of Arkansas Medical School, and became an obstetrician. She moved to Nashville in 1933, and set up a practice, becoming one of the first female ob/gyns in towns. She worked in Nashville until she retired in 1979. Annette Eskind was a casework supervisor for the Jewish Family Service for many years. She spent almost a decade on the local Board of Education and founded the Nashville Public Education Foundation. She and her husband, Irwin Eskind, endowed a biomedical library and a research chair in human development at the Vanderbilt University Medical School.

The most famous Jewish woman from Nashville was Fannye Rose Shore, who was born in Winchester, Tennessee, in 1917. She and her family moved to Nashville in 1923, and Fannye started singing on local radio while she was a student at Vanderbilt. When she graduated in 1938, she moved to New York to seek fortune and fame as Dinah Shore. After getting a break singing on the Eddie Cantor Radio Show, Dinah Shore became a star. She later hosted her own television talk show, which set the model for many of the daytime talk shows today.

Anti-Semitism in Nashville

While Nashville Jews have enjoyed general acceptance, during times of social turmoil they have sometimes become targets for extremists. After the Supreme Court’s Brown vs. Board of Education decision, Nashville was undergoing court-ordered school desegregation, and racial tensions were high. Dan May, the son of industrialist Jacob May, was chairman of the Nashville School Board at the time, and led the way toward adopting a school integration plan for the city. May received death threats and had to have special police protection for a period of time.

One night in March of 1958, a bomb went off at the entrance of the new JCC building on West End Avenue. Twenty minutes after the explosion, the bomber called Rabbi William Silverman of the Vine Street Temple and threatened to blow up the synagogue and other places that were sympathetic to the cause of African Americans. Silverman had been a vocal supporter of integration and some local Jews blamed his outspokenness for the attacks. The local newspaper denounced the bombing, writing that “decency stands appalled at the handiwork of some twisted mind” and an outpouring of support from government officials and church groups followed. Unbowed by the threats, Rabbi Silverman defended integration in a sermon to his congregants soon after, though he left the congregation two years later in 1960. Unfortunately, the police were never able to identify the perpetrator.

Rabbi Silverman’s successor, Randall Falk, also worked toward racial justice and harmony. In 1964, he led a Human Rights March with the pastor of a local Methodist Church. The following year he helped to found the Human Relations Commission, which advocated for peaceful integration. Nashville’s Reform temple remained in extremists’ cross hairs. In 1981, federal authorities arrested three members of the Ku Klux Klan as they were plotting to bomb the temple.

While Nashville Jews have enjoyed general acceptance, during times of social turmoil they have sometimes become targets for extremists. After the Supreme Court’s Brown vs. Board of Education decision, Nashville was undergoing court-ordered school desegregation, and racial tensions were high. Dan May, the son of industrialist Jacob May, was chairman of the Nashville School Board at the time, and led the way toward adopting a school integration plan for the city. May received death threats and had to have special police protection for a period of time.

One night in March of 1958, a bomb went off at the entrance of the new JCC building on West End Avenue. Twenty minutes after the explosion, the bomber called Rabbi William Silverman of the Vine Street Temple and threatened to blow up the synagogue and other places that were sympathetic to the cause of African Americans. Silverman had been a vocal supporter of integration and some local Jews blamed his outspokenness for the attacks. The local newspaper denounced the bombing, writing that “decency stands appalled at the handiwork of some twisted mind” and an outpouring of support from government officials and church groups followed. Unbowed by the threats, Rabbi Silverman defended integration in a sermon to his congregants soon after, though he left the congregation two years later in 1960. Unfortunately, the police were never able to identify the perpetrator.

Rabbi Silverman’s successor, Randall Falk, also worked toward racial justice and harmony. In 1964, he led a Human Rights March with the pastor of a local Methodist Church. The following year he helped to found the Human Relations Commission, which advocated for peaceful integration. Nashville’s Reform temple remained in extremists’ cross hairs. In 1981, federal authorities arrested three members of the Ku Klux Klan as they were plotting to bomb the temple.

The Second Half of the 20th Century

Despite periodic threats, the Nashville Jewish community continued to grow in the second half of the 20th century. The population had declined during the Great Depression and World War II, going from 4,000 Jews in 1927 to 2,900 in 1948. In 1948, Nashville was a Jewish community in transition. The community was still shaped by the immigrant era; 64% of Nashville Jews could speak or understand at least some Yiddish. Jews were still heavily concentrated in commercial trade, with 63% of male breadwinners being business owners or managers, and another 23% employed as salesmen or clerks. Only 10% of Nashville Jews were professionals. Unlike earlier eras in which high population turnover was the norm, the community was now relatively settled, with 64% having lived in Nashville for over 25 years. Also, Nashville Jews were starting to go to college in increasing numbers. Of those Jews between the ages of 18 and 29, 68% had some college education; of those over the age of 30, only 39% went beyond high school.The effect of this rising rate of college education can be seen 40 years later in 1988, when 48% of employed Nashville Jews were professionals.

Despite periodic threats, the Nashville Jewish community continued to grow in the second half of the 20th century. The population had declined during the Great Depression and World War II, going from 4,000 Jews in 1927 to 2,900 in 1948. In 1948, Nashville was a Jewish community in transition. The community was still shaped by the immigrant era; 64% of Nashville Jews could speak or understand at least some Yiddish. Jews were still heavily concentrated in commercial trade, with 63% of male breadwinners being business owners or managers, and another 23% employed as salesmen or clerks. Only 10% of Nashville Jews were professionals. Unlike earlier eras in which high population turnover was the norm, the community was now relatively settled, with 64% having lived in Nashville for over 25 years. Also, Nashville Jews were starting to go to college in increasing numbers. Of those Jews between the ages of 18 and 29, 68% had some college education; of those over the age of 30, only 39% went beyond high school.The effect of this rising rate of college education can be seen 40 years later in 1988, when 48% of employed Nashville Jews were professionals.

The Jewish Community in Nashville Today

By 1988, the Jewish community had almost doubled in size, growing to over 5,400, as Nashville became a regional economic center. Nashville itself has grown from 171,000 people in 1960 to 570,000 in 2000. The 1970s and 1980s saw an influx of Jews moving to Nashville. According to the 1988 survey, only 40% of Jews were born in Nashville, and 38% were born outside of the South. This growth has continued unabated over the past few decades. By 2002, almost 8,000 Jews lived in the Nashville metro area. Seventy-eight percent had at least a college degree, while 42% had a graduate degree. The community is very highly affiliated, with 83% of Jewish families belonging to a synagogue.

As Nashville’s Jewish population has grown, its Jewish community has matured, with a diversity of communal institutions. In 1936, the Nashville Jewish Welfare Fund was formed to unite the various local fundraising campaigns In 1948, its name was changed to the Nashville Jewish Community Council. In 1969, it became the Nashville Jewish Federation. The Jewish Observer newspaper has been covering the Nashville community since its founding in 1934 by Jacques Back. Back edited the newspaper until his death in 1975. In the early 1950s, Rabbi Zalman Posner and his wife Rita of Nashville’s Orthodox congregation, Sherith Israel, started the Akiva School, the city’s first Jewish day school. After being housed at Sherith Israel for almost 50 years, the school moved to the JCC campus in 1999.

The community has also seen an increase in the number of congregations in Nashville. In 1992, a faction split off from the city’s large Reform congregation, Ohabai Sholom, and formed Congregation Micah, which quickly flourished under the leadership of its first rabbi Ken Kanter. In 2001, the Chabad movement founded Congregation Beit Tefilah under the leadership of Rabbi Yitzchok Tiechtel.

Today, Nashville has emerged as the largest Jewish community in Tennessee, as it has continued to attract Jews from other parts of the country. With its plentiful economic opportunities and growing Jewish resources, Nashville has been able to keep much of its younger generation. Jews have gained a certain prominence and respect in Nashville, as shown by a recent decision to change the date of a local election since it conflicted with the Jewish holiday of Rosh Hashanah. Nashville has been increasingly recognized in the American Jewish world, hosting the large General Assembly meeting of the United Jewish Communities in 2007. Nashville is part of the new Jewish South that has flourished even as smaller Southern Jewish communities have faded.

As Nashville’s Jewish population has grown, its Jewish community has matured, with a diversity of communal institutions. In 1936, the Nashville Jewish Welfare Fund was formed to unite the various local fundraising campaigns In 1948, its name was changed to the Nashville Jewish Community Council. In 1969, it became the Nashville Jewish Federation. The Jewish Observer newspaper has been covering the Nashville community since its founding in 1934 by Jacques Back. Back edited the newspaper until his death in 1975. In the early 1950s, Rabbi Zalman Posner and his wife Rita of Nashville’s Orthodox congregation, Sherith Israel, started the Akiva School, the city’s first Jewish day school. After being housed at Sherith Israel for almost 50 years, the school moved to the JCC campus in 1999.

The community has also seen an increase in the number of congregations in Nashville. In 1992, a faction split off from the city’s large Reform congregation, Ohabai Sholom, and formed Congregation Micah, which quickly flourished under the leadership of its first rabbi Ken Kanter. In 2001, the Chabad movement founded Congregation Beit Tefilah under the leadership of Rabbi Yitzchok Tiechtel.

Today, Nashville has emerged as the largest Jewish community in Tennessee, as it has continued to attract Jews from other parts of the country. With its plentiful economic opportunities and growing Jewish resources, Nashville has been able to keep much of its younger generation. Jews have gained a certain prominence and respect in Nashville, as shown by a recent decision to change the date of a local election since it conflicted with the Jewish holiday of Rosh Hashanah. Nashville has been increasingly recognized in the American Jewish world, hosting the large General Assembly meeting of the United Jewish Communities in 2007. Nashville is part of the new Jewish South that has flourished even as smaller Southern Jewish communities have faded.