Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Mississippi

Overview >> Mississippi

Updates to the Mississippi section of the Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities have been made possible in part by the Mississippi Humanities Council under a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of the Mississippi Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Jews have always been a tiny minority of Mississippi’s population, and yet they have forged communities and preserved their religious traditions for over 160 years. There have been Jews in Mississippi since the 18th century, though the first significant Jewish community was not established until the first decade of the 19th century in Natchez. The first Jewish religious service was reportedly held in Natchez in 1800. The state’s oldest congregations are B’nai Israel (Children of Israel), formed in Natchez in 1840, and Anshe Chesed (Men of Kindness), formed in Vicksburg in 1841. The first Jewish house of worship was constructed by Beth Israel (House of Israel) Congregation in Jackson in the late 1860s.

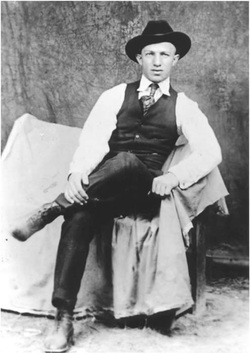

During the 19th century, Jewish immigrants from the German states and Alsace settled in Mississippi. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, they were joined by Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. Many of these Jewish immigrants initially worked as traveling peddlers. Since most Jews had been legally prevented from owning land in the Europe, they had no experience with farming. Legal discrimination made it hard for Jews in Europe to rely on someone else to support them economically, so they learned to support themselves through business ownership. When they came to the U.S., they drew on this entrepreneurial experience and became involved in commerce. These peddlers went from town to town, providing necessary supplies to farmers and their families. Often these peddlers received merchandise from wholesalers in Memphis or New Orleans, and traveled the state looking for customers.

During the 19th century, Jewish immigrants from the German states and Alsace settled in Mississippi. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, they were joined by Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. Many of these Jewish immigrants initially worked as traveling peddlers. Since most Jews had been legally prevented from owning land in the Europe, they had no experience with farming. Legal discrimination made it hard for Jews in Europe to rely on someone else to support them economically, so they learned to support themselves through business ownership. When they came to the U.S., they drew on this entrepreneurial experience and became involved in commerce. These peddlers went from town to town, providing necessary supplies to farmers and their families. Often these peddlers received merchandise from wholesalers in Memphis or New Orleans, and traveled the state looking for customers.

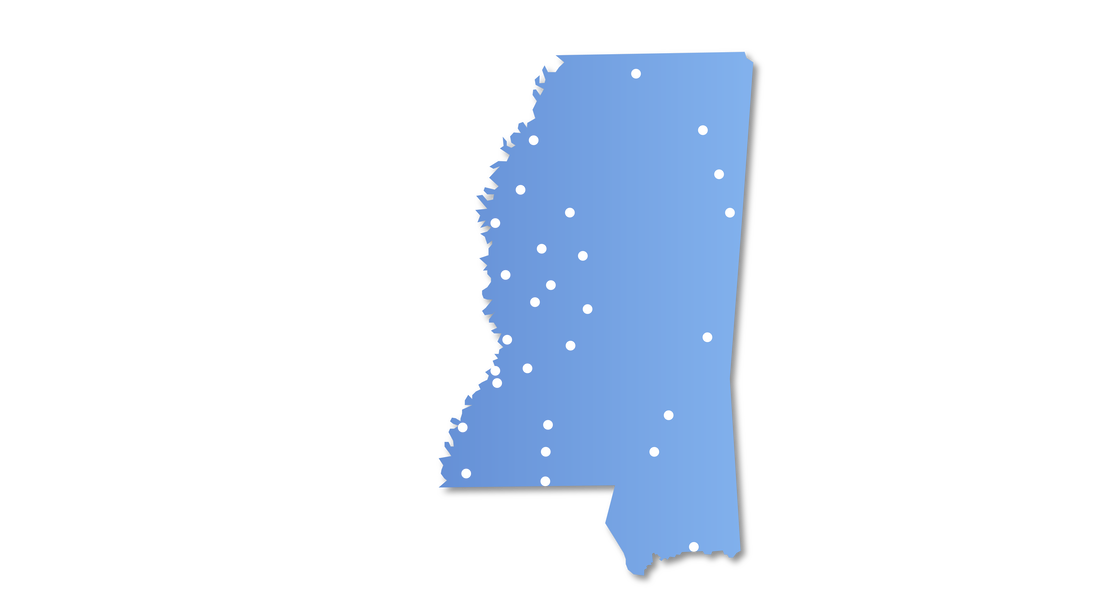

Once these peddlers, usually young single men, saved up enough money, they would open a store in one of the towns they had traveled through. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Jews spread themselves throughout the state. In 1937, Jews lived in 107 different Mississippi towns. In many of these places, Jewish merchants dominated main street. Jewish merchants specialized in clothes, shoes, and jewelry. Their prominent economic role gave them a visibility that transcended their relatively small numbers. The notable success story of these Jewish merchants was Stein Mart, now a national department store chain, which had its roots in a dry goods store founded by Russian Jewish immigrant Sam Stein in 1908 in Greenville.

This role as merchants brought great opportunity as well as real challenges. Since laws prevented Jewish merchants from opening their store on Sunday, most had no choice but to work on Saturday, the Jewish Sabbath, on which all work is traditionally prohibited. Jews sought to find ways to balance their religious traditions with the demands of their new home. In the early years of the 20th century, the Orthodox congregation in Meridian would hold religious services from 6 to 8 am in the morning on Saturday, enabling its members to worship on their Sabbath and still be able to open their stores. It was also very difficult to follow Jewish dietary restrictions in a place with no easily available supply of kosher meat. On matters of diet and Sabbath observance, Mississippi Jews were forced to adapt their traditional religious practices to fit their new environment. Most Mississippi Jews eventually embraced Reform Judaism, which used more English than Hebrew in its services and more closely resembled the Christian style of worship with choirs, organs, sermons, and mixed-gender seating.

This role as merchants brought great opportunity as well as real challenges. Since laws prevented Jewish merchants from opening their store on Sunday, most had no choice but to work on Saturday, the Jewish Sabbath, on which all work is traditionally prohibited. Jews sought to find ways to balance their religious traditions with the demands of their new home. In the early years of the 20th century, the Orthodox congregation in Meridian would hold religious services from 6 to 8 am in the morning on Saturday, enabling its members to worship on their Sabbath and still be able to open their stores. It was also very difficult to follow Jewish dietary restrictions in a place with no easily available supply of kosher meat. On matters of diet and Sabbath observance, Mississippi Jews were forced to adapt their traditional religious practices to fit their new environment. Most Mississippi Jews eventually embraced Reform Judaism, which used more English than Hebrew in its services and more closely resembled the Christian style of worship with choirs, organs, sermons, and mixed-gender seating.

For the most part, Jews have enjoyed remarkable acceptance in Mississippi. Several Mississippi Jews have been elected to local office, including at least 22 men who served as mayor of their town. Willie Sklar was mayor of Louise for 25 years, while Sam Rosenthal served as mayor of Rolling Fork for 40 years. Laurence Leyens is the current mayor of Vicksburg. This civic involvement was not unique to Mississippi, as Jews across the South were elected to public service positions. In each case, the vast majority of their votes came from non-Jews. In towns like Yazoo City, identity remained strong even when numbers remained small, and non-Jewish citizens even advocated for their Jewish neighbors.

One reason for this acceptance was that Jews assimilated to Southern culture. While remaining faithful to their unique religion and culture, Mississippi Jews have worked to lessen the barriers and differences between themselves and their gentile neighbors. They have embraced the cultural values of the region, for better or worse. Over 200 Mississippi Jews fought for the Confederacy during the Civil War. After the war, they celebrated Confederate Memorial Day, even those who had not even been in the United States at the time of the war. Many embraced the symbolism and mythology of the Old South. Jane Wexler, a Jewish woman, was the second queen of the Natchez Pilgrimage in 1932. Her mother was one of the founding members of the Pilgrimage organization. During the Civil Rights Movement, many Jews shared the prejudices of their white gentile neighbors, although others, inspired by their belief in Jewish values, spoke out in favor of racial equality and integration.

Indeed, anti-Semitism was most visible during the struggle over Civil Rights. In 1967, the Ku Klux Klan bombed Temple Beth Israel in Jackson and the home of its Rabbi, Perry Nussbaum, who advocated racial integration. Rabbi Nussbaum had traveled every week to Parchman State Prison in the summer of 1961 to minister to both Jewish and gentile freedom riders. He wrote many letters to parents of jailed freedom riders letting them know their children were okay. Several months later, the same Klan group bombed Temple Beth Israel in Meridian. The incidents galvanized much of the local gentile community who denounced these violent acts. Since the 1960s, Mississippi Jews have been in the forefront of building a better and more just community.

One reason for this acceptance was that Jews assimilated to Southern culture. While remaining faithful to their unique religion and culture, Mississippi Jews have worked to lessen the barriers and differences between themselves and their gentile neighbors. They have embraced the cultural values of the region, for better or worse. Over 200 Mississippi Jews fought for the Confederacy during the Civil War. After the war, they celebrated Confederate Memorial Day, even those who had not even been in the United States at the time of the war. Many embraced the symbolism and mythology of the Old South. Jane Wexler, a Jewish woman, was the second queen of the Natchez Pilgrimage in 1932. Her mother was one of the founding members of the Pilgrimage organization. During the Civil Rights Movement, many Jews shared the prejudices of their white gentile neighbors, although others, inspired by their belief in Jewish values, spoke out in favor of racial equality and integration.

Indeed, anti-Semitism was most visible during the struggle over Civil Rights. In 1967, the Ku Klux Klan bombed Temple Beth Israel in Jackson and the home of its Rabbi, Perry Nussbaum, who advocated racial integration. Rabbi Nussbaum had traveled every week to Parchman State Prison in the summer of 1961 to minister to both Jewish and gentile freedom riders. He wrote many letters to parents of jailed freedom riders letting them know their children were okay. Several months later, the same Klan group bombed Temple Beth Israel in Meridian. The incidents galvanized much of the local gentile community who denounced these violent acts. Since the 1960s, Mississippi Jews have been in the forefront of building a better and more just community.

Although Mississippi Jews worked hard to fit in, they also sought to maintain their distinct Jewish identity. Jewish parents encouraged their children to date and marry other Jews, which could be quite a challenge if only a few Jewish families lived in one’s town. As a result, Mississippi Jews built state and region-wide social networks to ensure that their children had access to Jewish peers. It was not unusual for Jewish teenagers to travel hours along Mississippi’s roads to attend balls and social mixers designed to introduce young Jews to potential spouses. The Henry S. Jacobs Camp, in Utica, founded in 1970, became one of the most significant Jewish experiences for young Jews in Mississippi and the surrounding areas. In 1986, camp director Macy B. Hart created the Museum of the Southern Jewish Experience, which now has sites in Utica and Natchez. The museum tells the story of Jewish life in the small towns of Mississippi and the rest of the South.

The Jewish population of Mississippi has been in decline for decades. It reached its peak in 1927, with 6,420 Jews. Since then, it has declined steadily. In 2001, only 1,500 Jews lived in Mississippi, with Jackson having the largest community. The Mississippi Delta, once the center of the state’s Jewish population, had 2,300 Jews in 1937, but now has less than 300. The generation of Jewish merchants produced children who became college-educated professionals and had little interest in taking over the family business. The decline of Mississippi’s rural economy and the rise of national retail chains have also pushed Mississippi Jews to such booming Sunbelt cities as Atlanta, Dallas, and Houston. In many Mississippi towns, empty storefronts line the main business streets. Jewish-sounding names are visible in sidewalk tiles in front of old buildings or on faded signs, testament to Jewish retailers’ former prominence in the community.

Today, there are 13 Jewish congregations in the state, though only two, Beth Israel in Jackson and B’nai Israel in Hattiesburg, employ full-time rabbis. Despite their small size, most of these congregations continue to hold regular worship services with lay leaders, student rabbis from the Jewish seminary in Cincinnati, Ohio, or retired visiting rabbis. Though their congregations are small, Mississippi Jews continue to follow their religious traditions, and have kept Judaism alive in the Magnolia State.

The Jewish population of Mississippi has been in decline for decades. It reached its peak in 1927, with 6,420 Jews. Since then, it has declined steadily. In 2001, only 1,500 Jews lived in Mississippi, with Jackson having the largest community. The Mississippi Delta, once the center of the state’s Jewish population, had 2,300 Jews in 1937, but now has less than 300. The generation of Jewish merchants produced children who became college-educated professionals and had little interest in taking over the family business. The decline of Mississippi’s rural economy and the rise of national retail chains have also pushed Mississippi Jews to such booming Sunbelt cities as Atlanta, Dallas, and Houston. In many Mississippi towns, empty storefronts line the main business streets. Jewish-sounding names are visible in sidewalk tiles in front of old buildings or on faded signs, testament to Jewish retailers’ former prominence in the community.

Today, there are 13 Jewish congregations in the state, though only two, Beth Israel in Jackson and B’nai Israel in Hattiesburg, employ full-time rabbis. Despite their small size, most of these congregations continue to hold regular worship services with lay leaders, student rabbis from the Jewish seminary in Cincinnati, Ohio, or retired visiting rabbis. Though their congregations are small, Mississippi Jews continue to follow their religious traditions, and have kept Judaism alive in the Magnolia State.

Selected Sources:

Edward Cohen, The Peddler’s Grandson: Growing Up Jewish in Mississippi (2001).

Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life, Cultural Corridors: Discovering Jewish Heritage across the South (2002).

The Mississippi Historical Records Survey Project, Inventory of the Church and Synagogue Archives of Mississippi: Jewish Congregations and Organizations (1940).

Jack Nelson, Terror in the Night: The Klan’s Campaign Against the Jews (1993).

Leo E. Turitz and Evelyn Turitz, Jews in Early Mississippi (1983).

Edward Cohen, The Peddler’s Grandson: Growing Up Jewish in Mississippi (2001).

Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life, Cultural Corridors: Discovering Jewish Heritage across the South (2002).

The Mississippi Historical Records Survey Project, Inventory of the Church and Synagogue Archives of Mississippi: Jewish Congregations and Organizations (1940).

Jack Nelson, Terror in the Night: The Klan’s Campaign Against the Jews (1993).

Leo E. Turitz and Evelyn Turitz, Jews in Early Mississippi (1983).