Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Rolling Fork, Mississippi

Overview >> Mississippi >> Rolling Fork

Overview

|

Rolling Fork, the seat of Sharkey County, is a small town in the southern portion of the Mississippi Delta region. The area has been home to complex human civilizations since at least 500 C.E., when an American Indian group constructed a large ceremonial site a few miles east of the eventual site of Rolling Fork. A handful of Euro-American settlers and enslaved Black workers farmed cotton in the area prior to the Civil War, but, as in other parts of the Delta, development accelerated following emancipation. Rolling Fork itself developed into a market hub after the arrival of the New Orleans and Texas Railroad in 1883.

The State of Mississippi created Sharkey County from parts of Issaquena, Warren, and Washington Counties in 1876, around the time that Jewish immigrants began to settle in the area. Jewish newcomers to Rolling Fork and nearby towns followed typical occupational patterns for the region, peddling drygoods door to door, setting up retail businesses, and then diversifying into agricultural endeavors when they had the means (and desire) to do so. While Jewish residents of Rolling Fork and Sharkey County attended synagogue in other parts of the Delta for most of their history, they did establish a congregation in Rolling Fork, which was active from 1953 until 1992. |

|

Early Jews in the Lower Mississippi Delta

One of the earliest examples of a Jewish presence near Rolling Fork was David Mayer, who founded Mayersville on the Mississippi River in Issaquena County in 1871. Mayer—born in Herxheim, Bavaria, in 1836—served in the Confederate Army and then settled in Vicksburg in 1866. He accumulated significant wealth as a cotton buyer, landowner, and merchant, using his stores to supply goods to the farm laborers (sharecroppers or tenant farmers) who grew cotton on his land. Mayer did not live in the town he founded, but members of his family settled there. While Mayersville served for a time as a busy riverport, the rise of rail shipping curtailed its development.

North of Rolling Fork, the Alsatian Jew Charles Blum established a store known as the Blum Company in Nitta Yuma around 1885. He also served as the Nitta Yuma postmaster from 1897 to 1899. Blum had left France after the Franco-Prussian War in 1873 and lived in Vicksburg, Marks, Rolling Fork, and Anguilla, Mississippi, before settling in Nitta Yuma. He ran the Blum Co. until the early 20th century, when he relocated to Shelby, Mississippi, in Bolivar County.

The Mississippi Delta cotton economy continued to attract Jewish newcomers throughout the late 19th century. Morris and Mollie Grundfest moved to the area in the mid-to-late 1890s. He started out as a peddler and then established the M. Grundfest store in Cary, a small town south of Rolling Fork. Like David Mayer, Morris Grundfest expanded beyond shopkeeping with the acquisition of 220 acres of farmland. According to a family story from Grundfest’s days as a peddler, he once encountered a white landowner who warned him never to set foot on his property again. Grundfest eventually purchased that land himself, and the Lamensdorf family (his descendants) still farm the land as of the early 21st century.

The Mississippi Delta cotton economy continued to attract Jewish newcomers throughout the late 19th century. Morris and Mollie Grundfest moved to the area in the mid-to-late 1890s. He started out as a peddler and then established the M. Grundfest store in Cary, a small town south of Rolling Fork. Like David Mayer, Morris Grundfest expanded beyond shopkeeping with the acquisition of 220 acres of farmland. According to a family story from Grundfest’s days as a peddler, he once encountered a white landowner who warned him never to set foot on his property again. Grundfest eventually purchased that land himself, and the Lamensdorf family (his descendants) still farm the land as of the early 21st century.

The Early 20th Century

In the early 20th century, the Jewish population of Sharkey County and nearby areas was too small or too widely dispersed to justify creating a local congregation. Those who wished to attend synagogue had to travel to Vicksburg or Greenville to do so. There were instances of Jewish organizational life, however. In 1905 a handful of local Jews formed the Deer Creek Zionists, named after the creek that flows through Anguilla, Rolling Fork, and Cary. The group affiliated with the American Federation of Zionists and elected S. Levin as its first secretary. Many Reform Jews in Mississippi eschewed Zionism at that time, and the Deer Creek Zionists were likely recent immigrants from Eastern Europe.

By the time that the Deer Creek Zionists became active, the Mississippi Delta’s Jewish population was on its way to surpassing that of other parts of the state. While cities such as Greenville and Clarksdale attracted many Jewish newcomers, others ventured to small towns throughout the area. Harris and Ida Danzig, for example, immigrated from Russia in the early twentieth century and settled in Midnight, Mississippi, in Humphreys County, where Harris was a merchant. They also lived in Anguilla before moving to New York city sometime before 1930. Their sons, Lou and Edwin, returned to the Delta, and Edwin eventually purchased a store in Rolling Fork from an uncle. Jewish retail stores such as Danzig’s played a prominent role in the economic life of small market towns, and Rolling Fork merchants often stayed open late into the night on Saturdays to accommodate crowds of shoppers who came in from the countryside. Merchant Dave Cohen used to ring a cowbell in the street at midnight to let customers and shopkeepers alike know that it was time to close for the night.

By the time that the Deer Creek Zionists became active, the Mississippi Delta’s Jewish population was on its way to surpassing that of other parts of the state. While cities such as Greenville and Clarksdale attracted many Jewish newcomers, others ventured to small towns throughout the area. Harris and Ida Danzig, for example, immigrated from Russia in the early twentieth century and settled in Midnight, Mississippi, in Humphreys County, where Harris was a merchant. They also lived in Anguilla before moving to New York city sometime before 1930. Their sons, Lou and Edwin, returned to the Delta, and Edwin eventually purchased a store in Rolling Fork from an uncle. Jewish retail stores such as Danzig’s played a prominent role in the economic life of small market towns, and Rolling Fork merchants often stayed open late into the night on Saturdays to accommodate crowds of shoppers who came in from the countryside. Merchant Dave Cohen used to ring a cowbell in the street at midnight to let customers and shopkeepers alike know that it was time to close for the night.

The Mid-20th Century

As the twentieth century progressed, Jews played prominent roles in the civic and economic life of Rolling Fork and surrounding towns. The most notable Jewish leader in the area was Sam Rosenthal, the mayor of Rolling Fork from 1924 to 1969. Known as “Mr. Sam,” Rosenthal was born in New York City, spent most of his childhood in Natchez, and joined his brother Monroe in Rolling Fork in 1919. When nearby levees broke during the 1927 Great Mississippi River Flood, Rosenthal helped evacuate Rolling Fork citizens on a train to Vicksburg. Although seven feet of water covered the town, Rosenthal stayed throughout the ordeal in order to lead relief and recovery efforts. During his 45-year tenure as mayor, he also oversaw street paving and projects and other civic improvements and helped attract industry to the tiny Delta town. Rosenthal retired from public service after losing his 1969 reelection bid, but he continued to run his clothing store.

Jewish families in the lower Mississippi Delta had worked hard to maintain religious and cultural traditions and to raise their children as Jews. Henry Kline had arrived in Anguilla in the 1880s and later taught Hebrew lessons to local Jewish children at his homes on Sundays. In the early 20th century, Edwin Danzig used to travel out of town to have his chickens slaughtered according to traditional dietary laws. Until 1953, however, the closest Jewish congregation—Greenville’s Hebrew Union Congregation—was 40 miles away..

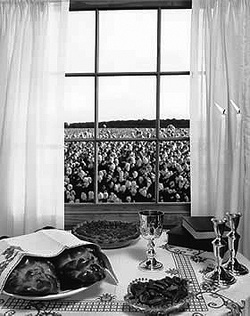

That year local Jews established the Henry Kline Memorial Congregation. They first came together in the home of Jack and Dorothy Grundfest and later at the parish house of the local Episcopal church. By the mid-1950s they also hosted community seders for Passover and hired Rabbi Herbert Hendel of Greenville to lead two Sunday services each month. The Sunday services took place in the evening and typically attracted between 40 and 50 worshipers. In 1956 the congregation constructed its own synagogue building.

The founding of the Henry Kline Memorial Congregation underscored a Jewish presence in the Rolling Fork area that had long been a visible part of the social fabric. In the 1950s the Rolling Rock High School football coach used to avoid scheduling football games on the High Holidays so that Bernard Danzig and other Jewish players would not have to miss a game. The Temple Youth held cake and rummage sales that raised money from the general public, and they hosted local clergy for discussions of non-Jewish faith traditions. Rolling Fork mayor Sam Rosenthal served as congregational president at one point, as did members of other local families.

Jewish families in the lower Mississippi Delta had worked hard to maintain religious and cultural traditions and to raise their children as Jews. Henry Kline had arrived in Anguilla in the 1880s and later taught Hebrew lessons to local Jewish children at his homes on Sundays. In the early 20th century, Edwin Danzig used to travel out of town to have his chickens slaughtered according to traditional dietary laws. Until 1953, however, the closest Jewish congregation—Greenville’s Hebrew Union Congregation—was 40 miles away..

That year local Jews established the Henry Kline Memorial Congregation. They first came together in the home of Jack and Dorothy Grundfest and later at the parish house of the local Episcopal church. By the mid-1950s they also hosted community seders for Passover and hired Rabbi Herbert Hendel of Greenville to lead two Sunday services each month. The Sunday services took place in the evening and typically attracted between 40 and 50 worshipers. In 1956 the congregation constructed its own synagogue building.

The founding of the Henry Kline Memorial Congregation underscored a Jewish presence in the Rolling Fork area that had long been a visible part of the social fabric. In the 1950s the Rolling Rock High School football coach used to avoid scheduling football games on the High Holidays so that Bernard Danzig and other Jewish players would not have to miss a game. The Temple Youth held cake and rummage sales that raised money from the general public, and they hosted local clergy for discussions of non-Jewish faith traditions. Rolling Fork mayor Sam Rosenthal served as congregational president at one point, as did members of other local families.

Small-Town Decline

The story of Jews in Rolling Fork and nearby towns mirrors that of other Delta communities. Whereas the local cotton economy once attracted Jewish settlers and provided them with opportunities to accumulate wealth, a series of changes decreased the viability of independent Jewish businesses. As agricultural mechanization, business consolidation, and the outmigration of Black farmworkers reshaped life in the Delta throughout the mid-to-late 20th century, most younger Jews left for educational and professional opportunities in larger population centers.

In Rolling Fork, synagogue membership remained strong through the 1980s. Greenville rabbis continued to lead services on a regular basis, and the congregation drew participation from Jewish families in Anguilla, Rolling Fork, and Cary. Eventually, however, the Rolling Fork congregation was unable to continue operation due to the area’s shrinking Jewish population. They closed their synagogue in 1992. Since then, the remaining Jews of Sharkey County have typically attended Hebrew Union Congregation in Greenville.

In Rolling Fork, synagogue membership remained strong through the 1980s. Greenville rabbis continued to lead services on a regular basis, and the congregation drew participation from Jewish families in Anguilla, Rolling Fork, and Cary. Eventually, however, the Rolling Fork congregation was unable to continue operation due to the area’s shrinking Jewish population. They closed their synagogue in 1992. Since then, the remaining Jews of Sharkey County have typically attended Hebrew Union Congregation in Greenville.

Seleceted Bibliography

Cash, William, “We have a fighting Spirit: Recollections of the flood of 1927 by South Deltans.” Delta Scene, 7, no: 8-10 (Spring 1980).

“Federation of American Zionists.” The American Israelite, Oct. 29, 1903.

Ferris, Marcie C., “Feeding the Jewish Soul in the Delta Diaspora.” Southern Cultures, 58, no. 3 (Fall 2004): 52-85.

Gordon, Mac, “Closing up Shop: Small Delta towns face fading sales.” The Clarion Ledger. Feb. 2, 1997.

“Historical, Cultural and Architecture Heritage Questionnaire.” Rolling Fork subject files, Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

Robertson, Craig, “’Mr. Sam recounts years as Rolling Fork.” The Delta Democratic Times. October 1, 1976.

Taulbert, Clifton, “They’re Jewish You Know.” Mississippi Jewish Record (March 1998).

Cash, William, “We have a fighting Spirit: Recollections of the flood of 1927 by South Deltans.” Delta Scene, 7, no: 8-10 (Spring 1980).

“Federation of American Zionists.” The American Israelite, Oct. 29, 1903.

Ferris, Marcie C., “Feeding the Jewish Soul in the Delta Diaspora.” Southern Cultures, 58, no. 3 (Fall 2004): 52-85.

Gordon, Mac, “Closing up Shop: Small Delta towns face fading sales.” The Clarion Ledger. Feb. 2, 1997.

“Historical, Cultural and Architecture Heritage Questionnaire.” Rolling Fork subject files, Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

Robertson, Craig, “’Mr. Sam recounts years as Rolling Fork.” The Delta Democratic Times. October 1, 1976.

Taulbert, Clifton, “They’re Jewish You Know.” Mississippi Jewish Record (March 1998).