Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Natchez, Mississippi

Overview >> Mississippi >> Natchez

Overview

|

The Natchez area was a seat of political and economic power for centuries prior to European arrival. Local mound building cultures prospered around 1200 C.E., and the European settlement of Natchez was eventually named after descendants of the earlier inhabitants. As the seat of Adams County, Natchez was the largest and wealthiest town in Mississippi before statehood in 1817 and maintained a leading commercial role in the state through its economic apex in the late 19th century. From the late 18th century until the Civil War, Natchez developed as a river port that specialized in the exchange of cotton and enslaved workers. Following the emancipation of African American slaves, the local economy continued to center around cotton production based on the sharecropping and tenant farmer systems.

The presence of Jewish settlers in the Natchez area likely precedes verifiable records, but the nucleus of a permanent Jewish community began to develop before the 1840s, when Natchez Jews formed the first Jewish institutions in Mississippi. During the late 19th century Natchez Jews constituted the largest and wealthiest Jewish community in the state. Just as Jewish growth followed the general fortunes of the town, however, the early-20th-century failure of the local cotton economy initiated a long period of Jewish decline. From a peak of 450 Jewish residents around 1905, the Natchez Jewish population numbered only a handful of people in 2020. |

Early Jewish Settlers

It is not clear who the first Jews to travel through the Natchez area may have been or when they did so, but the lower Mississippi attracted a variety of European traders and trappers during the colonial period. French settlers established a permanent settlement known as Fort Rosalie as the military and government center of the Natchez District in 1716. In 1722 the French instated the Black Code, which regulated slavery and barred Jewish residents from their North American colonies. The anti-Jewish policy was not always enforced, however, and itinerant Jews likely traded in the Natchez area under French rule. In the mid-18th century the British claimed the territory, and Jews became legal residents. Spain subsequently gained control, and court records from the 1760s to the 1790s demonstrate the presence of men whose names suggest Jewish lineages, including Isaac Mayes (Mayer), Robert Abrams, and Pedro Siegle.

The most famous 18th-century Jewish resident of the Natchez area was Benjamin Monsanto, a friend of Spanish Governor Gayose de Lemos. He and his wife, Clara, owned a 500-acre plantation on St. Catherine’s Creek, which runs to the south of the town and into the Mississippi River. Monsanto enslaved 17 people. He died suddenly in New Orleans in 1794. Other Jewish residents in the 1790s included Henry Jacobs, the first local Jewish resident to receive United States citizenship after the area came under the new nation’s control in 1798.

The Early 19th Century

By the time that Mississippi became a United States territory, Natchez had emerged as a significant hub of Euro-American settlement. Under Spanish administration in the 1790s local landowners shifted from raising cattle and growing tobacco to cotton cultivation, and the cotton economy dominated local life for more than a century. Cotton required a large agricultural workforce, and Natchez became a major site for the trade of enslaved people. The city served as the heart of political and economic power in Mississippi throughout the early 19th century, and Adams County—founded in 1899—boasted the largest population in Mississippi from the late colonial period until the 1840s. Enslaved Black workers accounted for the majority of all county residents until the advent of emancipation.

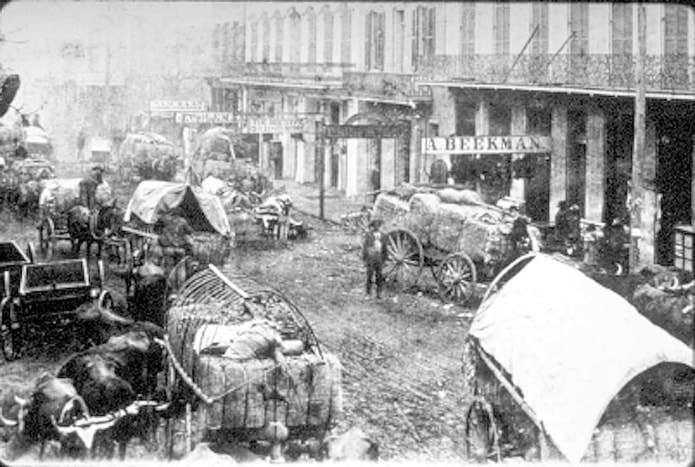

As Natchez developed during the first half of the 19th century, it began to attract permanent Jewish settlers, and the roots of an established Jewish community appeared by 1840. Most of the Jewish Natchez residents immigrated from Alsace-Lorraine and Bavaria, and they gravitated toward dry goods retail in the “Under-the-Hill” neighborhood, an entertainment and commercial district at the base of the bluffs that had a reputation for gambling and other illicit activities. In 1841 John Mayer and his wife arrived from New Orleans, and he worked in Natchez as a tailor and merchant for several decades. Merchants Aaron Beekman, Joseph Tillman, I. David, Solomon Bloom, and Simon Adler followed suit within a short time. While some Jewish businesses were short-lived, others became local institutions. S. Schatz, for example, was a retailer who specialized in ladies’ ready-to-wear and remained in business until the early 20th century. The preponderance of Jewish shops continued to trade in dry goods and clothing during the mid-19th century; an 1858 survey indicated that two-thirds of Natchez’s 12 Jewish-owned businesses specialized in such merchandise. While general population growth in Natchez faltered between 1840 and 1860, it remained the largest city in the state and boasted a higher proportion of immigrants than anywhere else in Mississippi.

Although there were reports of a Jewish minyan holding prayer services in the late 18th century, Organized Jewish life did not officially begin in Natchez until 1840, when a group of Jewish shopkeepers purchased land for a cemetery. Within a few years they established a chevrah kadisha (traditional burial society) made up of German-speaking immigrants. Joseph Deutch and Moses Hasan led efforts to organize the group, which held worship services in addition to performing burial ceremonies. When they registered with the state in 1848, they were the first Jewish organization in Mississippi to do so. (Vicksburg Jews had organized a congregation but had not yet incorporated.) The group waned somewhat before 1860, however, and they had ceased to meet by the early years of the Civil War.

The Civil War and Its Aftermath

In 1860 Natchez Jews were thoroughly enmeshed in white Mississippi society and a local economy that depended on enslaved workers as both a source of labor and also a form of capital. Enslaved Black people accounted for seventy percent of the county’s approximately 20,000 residents. As in other southern locales, Natchez Jews tended not to enslave large numbers of workers because they were not major landowners. A handful of local Jews, such as Joseph Tillman and John Mayer, appear in the 1860 United States Census Slave Schedule with a small number of enslaved workers who likely performed domestic work or manual labor in Jewish shops. The majority of Natchez Jews do not appear in the Slave Schedules. One Jewish Natchez resident, Jacob Soria, was more actively involved in the slave trade, as his auction house sold enslaved people (among other goods) beginning in the 1830s.

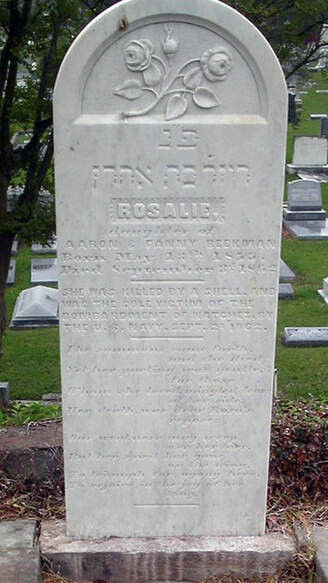

The headstone of Rosalie Beekman. Courtesy Historic Natchez Foundation.

The headstone of Rosalie Beekman. Courtesy Historic Natchez Foundation.

Following the outbreak of the Civil War in 1860, Natchez Jews generally supported the Confederate cause. Men joined the Confederate army, serving in a variety of units at a range of ranks. Simon Mayer rose to the rank of major. He was reportedly only 4-feet, eight-inches tall, and earned the nicknames “Too-Short-to-Shoot” and “the Little Mississippi Major.” When the Union Army occupied Natchez, some Jewish residents drew the ire of Union officials for insubordinate attitudes. At the same time, they formed close social ties with Jewish northerners who accompanied the United States Army as sutlers (civilian merchants who furnish goods to an army). Isaac Lowenburg and Henry Frank arrived with Union troops, made the acquaintance of John Mayer, and participated in local prayer services. Ultimately, Frank and Lowenburg married two of Mayer’s daughters.

Compared to other Mississippi towns, such as Jackson and Vicksburg, Natchez experienced relatively little violence or property destruction during the Civil War, because the town fell under Federal control shortly after the Union victory in New Orleans in 1862. However, a Union gunboat did fire on the town in September 1862, killing 7-year-old Rosalie Beekman, the daughter of Aaron and Fanny Beekman. She was the only person in Natchez to die directly from the attack.

After the Union victory and the emancipation of enslaved Black southerners, Natchez and other southern cities went through a period of rapid change. Natchez briefly became a center of Black political power before white Mississippians curtailed the advancement of formerly enslaved people through violence, intimidation, and legal restrictions. Plantation owners resorted to selling off land in order to secure cash, even as the cotton economy reorganized itself around sharecropping and tenant farming. Where major landholders once occupied the top rung of Natchez society, merchants gained status in the postwar order, and Jewish Natchez soon reached the apex of its social and political influence.

Compared to other Mississippi towns, such as Jackson and Vicksburg, Natchez experienced relatively little violence or property destruction during the Civil War, because the town fell under Federal control shortly after the Union victory in New Orleans in 1862. However, a Union gunboat did fire on the town in September 1862, killing 7-year-old Rosalie Beekman, the daughter of Aaron and Fanny Beekman. She was the only person in Natchez to die directly from the attack.

After the Union victory and the emancipation of enslaved Black southerners, Natchez and other southern cities went through a period of rapid change. Natchez briefly became a center of Black political power before white Mississippians curtailed the advancement of formerly enslaved people through violence, intimidation, and legal restrictions. Plantation owners resorted to selling off land in order to secure cash, even as the cotton economy reorganized itself around sharecropping and tenant farming. Where major landholders once occupied the top rung of Natchez society, merchants gained status in the postwar order, and Jewish Natchez soon reached the apex of its social and political influence.

Clara Lowenburg Moses (1865-1951) was the daughter of Isaac and Ophelia Lowenburg and came of age during a period of increasing affluence and social capital for established Natchez Jews. Photo c. 1880s.

Clara Lowenburg Moses (1865-1951) was the daughter of Isaac and Ophelia Lowenburg and came of age during a period of increasing affluence and social capital for established Natchez Jews. Photo c. 1880s.

Natchez had long attracted a higher number of immigrants than other parts of Mississippi, and Jewish citizens constituted up to five percent of the local white population in the late 19th century—a massive proportion compared to elsewhere in the state. The local Jewish population reached 200 individuals by the late 1870s, and they owned one-third of the city’s business. That high level of Jewish representation in the business world led to prominence in other arenas as well. Jewish men served as aldermen and county representatives. They also participated in fraternal organizations such as the Masons and Oddfellows, volunteered for the fire department, and served as founders and board members of local banks. Even more notably, the city elected Isaac Lowenburg, the German native who had arrived with the Union Army, to two mayoral terms in the 1880s.

Further evidence of Jewish success and social acceptance came in the opulent homes that several Jewish families purchased or built in the late 19th century. By 1886 the majority of the Natchez Jewish population was native-born, and acculturation influenced their work opportunities. In addition to common Jewish occupations such as merchant, clerk, shoemaker, or peddler, a few Jewish residents made their livings in the professions. Dr. Phillip Beekman ran a surgical practice, and A.H. Geisenberg, Sim H. Lowenburg (brother of Clara Lowenburg Moses), and Julius Lemkowitz all worked as attorneys. The 1900 census lists Cassius Tillman as a deputy sheriff, and he served as a county treasurer and schoolboard member; he also owned a cigar store and saloon.

Further evidence of Jewish success and social acceptance came in the opulent homes that several Jewish families purchased or built in the late 19th century. By 1886 the majority of the Natchez Jewish population was native-born, and acculturation influenced their work opportunities. In addition to common Jewish occupations such as merchant, clerk, shoemaker, or peddler, a few Jewish residents made their livings in the professions. Dr. Phillip Beekman ran a surgical practice, and A.H. Geisenberg, Sim H. Lowenburg (brother of Clara Lowenburg Moses), and Julius Lemkowitz all worked as attorneys. The 1900 census lists Cassius Tillman as a deputy sheriff, and he served as a county treasurer and schoolboard member; he also owned a cigar store and saloon.

Religious Life

At the end of the Civil War the Jewish community of Natchez still followed Orthodox practices whenever possible. The chevrah kadisha resumed activity in 1861 with John Mayer as president. Lay leaders conducted services in borrowed rooms above members’ stores. Membership required a five-dollar initiation fee followed by one-dollar monthly dues, and the small congregation assessed fines for members who failed to attend meetings. At that time only large Jewish communities in the United States employed rabbis, so the Natchez Jewish community regularly sought transplants who could act as shochets (kosher butchers), teachers, or cantors.

As the local Jewish community resumed regular activities, some of its increasingly acculturated membership advocated for changes in religious practice. Samuel Ullman, a German immigrant, sought to adopt Reform traditions that would involve women and children in synagogue life. When the community purchased land for a future synagogue in 1866, the question of where to place the bimah (raised platform for service leaders) split the congregation. Traditionalists preferred a European-style bimah, which would sit in the middle of the sanctuary and face the ark, while the Reform camp favored a bimah at the front of the space with prayer leaders facing the congregation. The Reform contingent eventually won out; in 1871 the congregation adopted Reform practice and renamed itself B’nai Israel (children of Israel). In 1873 B’nai Israel became a founding member of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, the governing body of the Reform movement in the United States. Samuel Ullman and the other Reform advocates additionally sought to curtail the possibility of an Orthodox splinter group by imposing penalties on Jewish community members who broke with the congregation.

As the local Jewish community resumed regular activities, some of its increasingly acculturated membership advocated for changes in religious practice. Samuel Ullman, a German immigrant, sought to adopt Reform traditions that would involve women and children in synagogue life. When the community purchased land for a future synagogue in 1866, the question of where to place the bimah (raised platform for service leaders) split the congregation. Traditionalists preferred a European-style bimah, which would sit in the middle of the sanctuary and face the ark, while the Reform camp favored a bimah at the front of the space with prayer leaders facing the congregation. The Reform contingent eventually won out; in 1871 the congregation adopted Reform practice and renamed itself B’nai Israel (children of Israel). In 1873 B’nai Israel became a founding member of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, the governing body of the Reform movement in the United States. Samuel Ullman and the other Reform advocates additionally sought to curtail the possibility of an Orthodox splinter group by imposing penalties on Jewish community members who broke with the congregation.

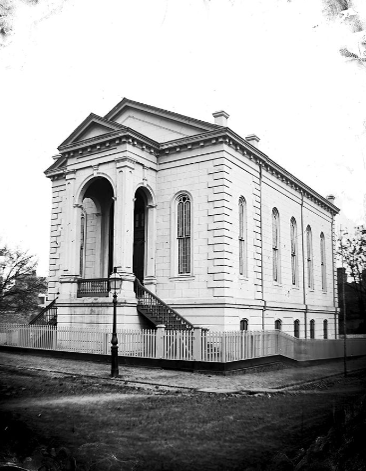

The original B'nai Israel synagogue, photographed in 1880. Dr. Thomas H. and Joan W. Gandy Collection, Special Collections, Hill Memorial Library, Louisiana State University

The original B'nai Israel synagogue, photographed in 1880. Dr. Thomas H. and Joan W. Gandy Collection, Special Collections, Hill Memorial Library, Louisiana State University

In 1870 B’nai Israel celebrated the cornerstone laying for its first synagogue at a ceremony officiated by Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, the founder of American Reform Judaism. Around the time of the building’s dedication in 1872, Isaac Lowenburg presented the congregation with a Torah scroll that he had obtained in his hometown of Hechingen, Germany. Other Natchez families, including the Ullmans, Geisenbergers, and Benjamins, also had connections to the Hechingen community. Reverend Aaron Norden served as the first Jewish clergyperson in Natchez, but he only stayed for a short period before leaving for Baltimore. (American Reform spiritual leaders commonly took the honorific “reverend” at that time.) Just as Natchez Jews had a “reverend,” they adopted other elements of Reform practice that mirrored the Protestant traditions around them: English language prayers, a formal choir, and pipe organ accompaniment. However, records from the time suggest that these innovations did not improve attendance at religious services.

Although the congregation’s formal leadership consisted exclusively of men, women made major contributions to Jewish life in the city. In 1865 the women of Natchez’s Jewish congregation formalized their involvement through the creation of the Hebrew Ladies’ Benevolent Association, renamed the Hebrew Ladies’ Aid Association shortly thereafter. While local Jewish women over the age of sixteen were invited to join, only married women could serve as president or vice president. The founding officers of the association were Mrs. C. Haase, Mrs. C. Mendelson, Mrs. S. Lemle, and Mrs. B. Paradise. The women administered the congregational Sunday school and raised money through public programs including fairs and balls. The Hebrew Ladies’ Aid Association continued to function into the 1940s even as other Jewish women’s groups emerged in Natchez—a local sisterhood and a chapter of the National Council for Jewish Women—in the 1890s.

Although the congregation’s formal leadership consisted exclusively of men, women made major contributions to Jewish life in the city. In 1865 the women of Natchez’s Jewish congregation formalized their involvement through the creation of the Hebrew Ladies’ Benevolent Association, renamed the Hebrew Ladies’ Aid Association shortly thereafter. While local Jewish women over the age of sixteen were invited to join, only married women could serve as president or vice president. The founding officers of the association were Mrs. C. Haase, Mrs. C. Mendelson, Mrs. S. Lemle, and Mrs. B. Paradise. The women administered the congregational Sunday school and raised money through public programs including fairs and balls. The Hebrew Ladies’ Aid Association continued to function into the 1940s even as other Jewish women’s groups emerged in Natchez—a local sisterhood and a chapter of the National Council for Jewish Women—in the 1890s.

Prominent Jewish merchants in Natchez also formed a Jewish social club in the 1890s. The Standard Club was located at the corner of Franklin and Pearl Streets on the second floor of the Seiferth Dry Goods building. It hosted balls, dances, and other social events in its ballroom, and offered a comfortable environment for playing cards and billiards. Jewish clubs such as this were common in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a period when some white Christian organizations imposed new restrictions on Jewish participation.

The Early 20th Century

The Natchez Jewish community reached its numerical peak shortly after the turn of the century. B’nai Israel’s membership stood at 150 families in 1902, and the religious school enrolled 75 students. Whereas the congregation had experienced frequent rabbinical turnover in prior decades, an era of stable leadership began in 1899 with the hiring of Rabbi Seymour Bottigheimer, a Virginia native and graduate of Hebrew Union College who remained in Natchez for 15 years.

The 1905 B'nai Israel synagogue, c. 1990. Photo by Bill Aron.

The 1905 B'nai Israel synagogue, c. 1990. Photo by Bill Aron.

Unfortunately, a 1903 fire at the original B’nai Israel synagogue disrupted the successes of the early 20th century. As the congregation made plans for a new building, they were assisted by Christian neighbors. A Methodist congregation allowed them temporary use of its church as a worship space, and many affluent white Christians donated to the building fund. When the congregation completed construction on the new synagogue in 1905, a reported 600 people attended, including local dignitaries and Jewish leaders from other Mississippi cities. Natchez had 450 Jewish residents at that time, representing the historical peak of the Jewish population.

The 1905 synagogue was designed by architect H.A. Overbeck of Dallas, Texas, who later used a very similar plan for Greenville’s Hebrew Union Temple. The synagogue is an example of the Beaux-Arts style, with arched, stained glass windows, a prominent central dome, and an ornate ark constructed from Italian marble. A brand-new organ provided instrumental accompaniment at most services. The sanctuary was built to seat 450 people with additional seating in the balcony. While the building represented the wealth and prominence of the Natchez Jewish community at the time of its construction, the congregation never had a need for the overflow seating.

By the end of the decade, flooding from the Mississippi River and the arrival of the boll weevil posed new challenges for Natchez and its Jewish community. As flooding damaged businesses and the boll weevil drastically reduced cotton yields, these setbacks also highlighted long-standing weaknesses in local and regional economies based around debt-financed, single-crop agriculture. Several Jewish businesses closed in the following years, and B’nai Israel began to lose members. When Rabbi Bottigheimer departed in 1913, the congregation once again entered a period of quick rabbinical turnover that lasted until the 1950s. Additionally, the formerly stable and affluent congregation struggled to pay membership fees to the Union of American Hebrew Congregations and even considered leaving the Reform movement.

The 1905 synagogue was designed by architect H.A. Overbeck of Dallas, Texas, who later used a very similar plan for Greenville’s Hebrew Union Temple. The synagogue is an example of the Beaux-Arts style, with arched, stained glass windows, a prominent central dome, and an ornate ark constructed from Italian marble. A brand-new organ provided instrumental accompaniment at most services. The sanctuary was built to seat 450 people with additional seating in the balcony. While the building represented the wealth and prominence of the Natchez Jewish community at the time of its construction, the congregation never had a need for the overflow seating.

By the end of the decade, flooding from the Mississippi River and the arrival of the boll weevil posed new challenges for Natchez and its Jewish community. As flooding damaged businesses and the boll weevil drastically reduced cotton yields, these setbacks also highlighted long-standing weaknesses in local and regional economies based around debt-financed, single-crop agriculture. Several Jewish businesses closed in the following years, and B’nai Israel began to lose members. When Rabbi Bottigheimer departed in 1913, the congregation once again entered a period of quick rabbinical turnover that lasted until the 1950s. Additionally, the formerly stable and affluent congregation struggled to pay membership fees to the Union of American Hebrew Congregations and even considered leaving the Reform movement.

Jane Wexler, Queen of the Natchez Pilgrimage, 1935.

Jane Wexler, Queen of the Natchez Pilgrimage, 1935.

In 1927 Natchez was home to 150 Jewish residents, one-third of the former Jewish population, but despite Natchez Jews’ reduced numbers and the city’s overall decline in prominence, Jewish life continued. Young Jewish men served in the United States Armed Forces during World War I, and local Jewish women volunteered for the Red Cross. In 1927, New Orleans resident Isadore Levy (who was born to a Jewish father but did not practice Judaism) and his sons built the beautiful Eola Hotel, named for Isidore’s daughter. The Levy family ran the hotel until the stock market crash in 1929, when poor finances forced them to close it. In 1936, there were still 19 businesses under Jewish ownership in Natchez. Such Natchez institutions included Geisenberger & Friedler, Krouse Pecan Co., and Abrams Department Store.

Jews also continued to enjoy a high degree of acceptance from white, non-Jewish peers, and they demonstrated a high level of acculturation. Saul Laub served six years as mayor beginning in 1929. Jane Wexler, a young Jewish woman, served as queen of the Natchez Pilgrimage in 1935. Her mother, Emma Marks, was an early volunteer for the event, which attracted locals and out-of-town visitors alike to the grand antebellum homes in the area. The pilgrimage began in 1932 as a source of revenue for the Natchez Garden Club, and it typified Confederate pageantry and nostalgic depictions of slave society. Jewish participation in this and similar events demonstrated a general acceptance of “Lost Cause” revisionism, which romanticized former practices of enslavement while continuing to justify Jim Crow segregation in the early 20th century.

Jews also continued to enjoy a high degree of acceptance from white, non-Jewish peers, and they demonstrated a high level of acculturation. Saul Laub served six years as mayor beginning in 1929. Jane Wexler, a young Jewish woman, served as queen of the Natchez Pilgrimage in 1935. Her mother, Emma Marks, was an early volunteer for the event, which attracted locals and out-of-town visitors alike to the grand antebellum homes in the area. The pilgrimage began in 1932 as a source of revenue for the Natchez Garden Club, and it typified Confederate pageantry and nostalgic depictions of slave society. Jewish participation in this and similar events demonstrated a general acceptance of “Lost Cause” revisionism, which romanticized former practices of enslavement while continuing to justify Jim Crow segregation in the early 20th century.

A Long Decline

Interior of Temple B'nai Israel, c. 2013.

Interior of Temple B'nai Israel, c. 2013.

By 1940 the membership at B’nai Israel had fallen to approximately ninety members. While Natchez Jews made up most of the congregation, others came from Fayette, Bude, and Lorman as well as the Louisiana towns of Ferriday, Waterproof, and Winnsboro. There are also records of members from New Orleans even though the crescent city was hours away. While classical Reform Judaism still prevailed with weddings, funerals, and confirmation ceremonies, there was an occasional bar mitzvah as far back as the 1940s. Despite financial struggles, the congregation continued to support charitable causes. In 1947 the United Jewish Appeal organized in Natchez, raising $7,714. The Jewish Relief Association of the early 1900s persisted through the mid-twentieth century.

B’nai Israel continued to experience frequent rabbinical turnover. Twelve rabbis served an average of three-and-one-half years each from 1913 to 1955. Six more rabbis came and went before the death of Rabbi Arthur Liebowitz in 1976 marked the end of full-time rabbinical services for the congregation. Since then, B’nai Israel has relied on lay leaders, student rabbis from Hebrew Union College, and visiting rabbis (including from the Institute of Southern Jewish Life).

The continued decline of the local Jewish population during the late 20th century and early 21st centuries has forced Temple B’nai Israel members to make plans for the eventual dissolution of the congregation. By 1979 fewer than thirty families belonged to B’nai Israel, and membership dropped to fewer than ten individuals in the early 21st century. The small group persisted with monthly services and holiday celebrations, however, due to dedicated leadership of members like Jay Lehmann, who served as congregational president for decades. In 1991 the congregation deeded its building to what is now the Institute of Southern Jewish Life (ISJL), and the organization continues to manage the building’s maintenance in 2022. B’nai Israel and the ISJL secured grant money from the Mississippi Department of Archives and History for much-needed updates and repairs in 2016 and 2019, in hopes that the historic synagogue can find continued use as a performance and meeting space, and will continue to testify to the long history of Jewish Natchez. In the meantime, Natchez remains home to a small but dedicated Jewish community, who continue to hold lay-led Shabbat evening services and holiday celebrations in their historic building.

B’nai Israel continued to experience frequent rabbinical turnover. Twelve rabbis served an average of three-and-one-half years each from 1913 to 1955. Six more rabbis came and went before the death of Rabbi Arthur Liebowitz in 1976 marked the end of full-time rabbinical services for the congregation. Since then, B’nai Israel has relied on lay leaders, student rabbis from Hebrew Union College, and visiting rabbis (including from the Institute of Southern Jewish Life).

The continued decline of the local Jewish population during the late 20th century and early 21st centuries has forced Temple B’nai Israel members to make plans for the eventual dissolution of the congregation. By 1979 fewer than thirty families belonged to B’nai Israel, and membership dropped to fewer than ten individuals in the early 21st century. The small group persisted with monthly services and holiday celebrations, however, due to dedicated leadership of members like Jay Lehmann, who served as congregational president for decades. In 1991 the congregation deeded its building to what is now the Institute of Southern Jewish Life (ISJL), and the organization continues to manage the building’s maintenance in 2022. B’nai Israel and the ISJL secured grant money from the Mississippi Department of Archives and History for much-needed updates and repairs in 2016 and 2019, in hopes that the historic synagogue can find continued use as a performance and meeting space, and will continue to testify to the long history of Jewish Natchez. In the meantime, Natchez remains home to a small but dedicated Jewish community, who continue to hold lay-led Shabbat evening services and holiday celebrations in their historic building.

last updated, Feb. 24., 2022