Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Dallas, Texas

Historical Overview

|

In a short history of Dallas’ Jewish community written in 1910, Rabbi William Greenburg declared “the history of the Jews of Dallas is the history of the growth and advancement of the city itself.” More than a century later, Greenburg’s point about the inextricable link between Dallas Jews and the city in which they found a home remains just as true.

Chartered in 1856, Dallas got its start as a frontier trading town. With the rise of plantation agriculture in northeast Texas, Dallas emerged as a regional center for the cotton trade. But it was not until 1872, when town leaders convinced the Houston & Texas Central Railroad to build their tracks one mile east of the courthouse, that the town started down the path to becoming the “Big D,” one of the largest cities in the South. The Texas & Pacific Railroad came in 1873, giving the town both a north-south and east-west line, and helping to transform Dallas from a small frontier outpost to a major cotton shipping nexus and thriving city. |

Stories of the Jewish Community in Dallas

Sanger Brother store c. 1890.

Sanger Brother store c. 1890. Photo courtesy of the

Dallas Jewish Historical Society.

Early Settlers

Jews were among the earliest settlers in Dallas. By the time of the Civil War, a small number of Jews owned stores along Main Street. Some, like Polish-born Alex Simon, did not stay in town very long. Simon owned a store in town by 1858, but moved to Brenham in 1863. Once the railroad came to town, Dallas became a much more attractive place to open a business, and the town’s Jewish population began to grow quickly. By 1873, Jews owned 12 of the city’s 29 dry goods stores.

Once tracks were laid in Dallas it was inevitable that the Sanger brothers would soon follow. Starting in Millican, Texas, the German-born brothers followed the progress of the Houston & Texas Central Railroad, opening new dry goods stores in each town as the tracks moved northward. In 1872, they opened a branch in Dallas, with Alex Sanger coming to manage it. The store was a huge success, and a year later Alex moved to a new 10,000 square foot location, reportedly the largest store in the state at the time. Alex's brother, Philip Sanger, soon came to help with the business; the two opened a wholesale operation, which supplied small town stores and peddlers throughout the area. In 1879, traveling journalist Charles Wessolowsky called the Sanger Brothers store “an establishment of grandeur, taste, and elegance equal to any in the South,” and likened it to the leading stores in New York City. By 1890, the business employed 250 people and later moved into an 8-story building at Main & Lamar streets.

The Sangers were not alone in finding economic opportunity in Dallas. E.M. Tillman and Moses Ullman owned a grocery, liquor, and tobacco business. E.M. Kahn opened a men’s clothing store in 1872 that soon grew into a Dallas institution, remaining in business for over a century. These early Jewish merchants were closely involved in Dallas’s public life as their commercial role opened the door to positions of civic leadership. E.M. Tillman was elected alderman in 1880 and later served on the city’s first school board. E.M. Kahn was president of the local Masonic Lodge and served on the board of the state fair association. Alex Sanger was elected alderman in 1873, only a year after he arrived in Dallas. Two years later Sanger became president of the local volunteer fire department, in which 17 Jews had volunteered to serve in 1873. In 1886, Sanger helped organize the Dallas State Fair and Exposition Association, which created the annual state fair. Sanger became one of Dallas’ most prominent citizens, serving on the Board of Regents of the University of Texas in the 1910s. When Alex Sanger died in 1925, the Dallas Morning News eulogized him as a builder of Dallas, writing that “the city that mourns his death is in truth a monument to him.” After Alex’s death, the family sold the store, although it retained the Sanger name.

Jews were among the earliest settlers in Dallas. By the time of the Civil War, a small number of Jews owned stores along Main Street. Some, like Polish-born Alex Simon, did not stay in town very long. Simon owned a store in town by 1858, but moved to Brenham in 1863. Once the railroad came to town, Dallas became a much more attractive place to open a business, and the town’s Jewish population began to grow quickly. By 1873, Jews owned 12 of the city’s 29 dry goods stores.

Once tracks were laid in Dallas it was inevitable that the Sanger brothers would soon follow. Starting in Millican, Texas, the German-born brothers followed the progress of the Houston & Texas Central Railroad, opening new dry goods stores in each town as the tracks moved northward. In 1872, they opened a branch in Dallas, with Alex Sanger coming to manage it. The store was a huge success, and a year later Alex moved to a new 10,000 square foot location, reportedly the largest store in the state at the time. Alex's brother, Philip Sanger, soon came to help with the business; the two opened a wholesale operation, which supplied small town stores and peddlers throughout the area. In 1879, traveling journalist Charles Wessolowsky called the Sanger Brothers store “an establishment of grandeur, taste, and elegance equal to any in the South,” and likened it to the leading stores in New York City. By 1890, the business employed 250 people and later moved into an 8-story building at Main & Lamar streets.

The Sangers were not alone in finding economic opportunity in Dallas. E.M. Tillman and Moses Ullman owned a grocery, liquor, and tobacco business. E.M. Kahn opened a men’s clothing store in 1872 that soon grew into a Dallas institution, remaining in business for over a century. These early Jewish merchants were closely involved in Dallas’s public life as their commercial role opened the door to positions of civic leadership. E.M. Tillman was elected alderman in 1880 and later served on the city’s first school board. E.M. Kahn was president of the local Masonic Lodge and served on the board of the state fair association. Alex Sanger was elected alderman in 1873, only a year after he arrived in Dallas. Two years later Sanger became president of the local volunteer fire department, in which 17 Jews had volunteered to serve in 1873. In 1886, Sanger helped organize the Dallas State Fair and Exposition Association, which created the annual state fair. Sanger became one of Dallas’ most prominent citizens, serving on the Board of Regents of the University of Texas in the 1910s. When Alex Sanger died in 1925, the Dallas Morning News eulogized him as a builder of Dallas, writing that “the city that mourns his death is in truth a monument to him.” After Alex’s death, the family sold the store, although it retained the Sanger name.

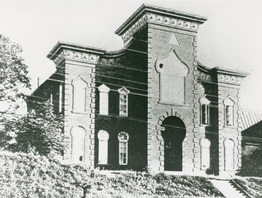

Emanu-El's first synagogue, built in 1876.

Emanu-El's first synagogue, built in 1876. Photo courtesy of the

Dallas Jewish Historical Society.

Organized Jewish Life in Dallas

By 1872, an estimated 60 to 70 Jews lived in Dallas. That summer, 11 men founded the city’s first Jewish organization, the Hebrew Benevolent Association, with Moses Ullman as president and Alex Sanger as vice president. Among their first actions were to plan High Holiday services and buy land for a cemetery. For Rosh Hashanah in 1872 the group held services at the local Masonic temple. Using a Torah borrowed from a New Orleans congregation, Aaron Miller acted as lay leader for the service. In 1873, the group purchased their own Torah. That same year, Dallas Jews established a chapter of B’nai B’rith, a national Jewish fraternal organization.

In 1874, 40 members of the Hebrew Benevolent Association founded Congregation Emanu-El. Initially, the fledgling congregation met in the B’nai B’rith hall above the Sanger Brothers store. David Goslin was the congregation’s first president, with Philip Sanger serving as vice president. Emanu-El took over management of the Hebrew Benevolent Association’s cemetery. The Jewish women in Dallas established the Ladies Hebrew Benevolent Society in 1875, which was affiliated with Emanu-El. In fact, at their first meeting, the members of the society voted “to induce the Hebrew gentlemen to procure a place of worship.”

The members of Emanu-El acted quickly, constructing a synagogue in 1876 on land owned by the B’nai B’rith lodge. Costing $15,000, the Moorish revival synagogue included classrooms and a meeting space for local Jewish lodges. Initially, the classrooms housed a secular, non-sectarian elementary school during the week, while Alice Levy ran the Sunday school for the congregation. From the outset, Emanu-El was Reform in orientation, voting to adopt Isaac Mayer Wise’s Minhag America prayer book in 1874. In 1875, they hired Aaron Suhler as their first full-time rabbi. For their first decade or so, Emanu-El had several short-term rabbis. Rabbi Edward Chapman led the congregation from 1885 to 1897. In 1882, the congregation experienced a brief schism when a group of disgruntled members created Congregation Ahavas Shalom. By 1884, the breakaway group had returned to Emanu-El, and the congregation grew steadily. Soon they outgrew their building, leading Emanu-El’s 100 members to construct a new temple on South Ervay Street in 1899. They only stayed in this new temple for 18 years, as the congregation doubled during this period. In 1917, they built a new larger synagogue, which featured a gym, on South Boulevard.

By 1872, an estimated 60 to 70 Jews lived in Dallas. That summer, 11 men founded the city’s first Jewish organization, the Hebrew Benevolent Association, with Moses Ullman as president and Alex Sanger as vice president. Among their first actions were to plan High Holiday services and buy land for a cemetery. For Rosh Hashanah in 1872 the group held services at the local Masonic temple. Using a Torah borrowed from a New Orleans congregation, Aaron Miller acted as lay leader for the service. In 1873, the group purchased their own Torah. That same year, Dallas Jews established a chapter of B’nai B’rith, a national Jewish fraternal organization.

In 1874, 40 members of the Hebrew Benevolent Association founded Congregation Emanu-El. Initially, the fledgling congregation met in the B’nai B’rith hall above the Sanger Brothers store. David Goslin was the congregation’s first president, with Philip Sanger serving as vice president. Emanu-El took over management of the Hebrew Benevolent Association’s cemetery. The Jewish women in Dallas established the Ladies Hebrew Benevolent Society in 1875, which was affiliated with Emanu-El. In fact, at their first meeting, the members of the society voted “to induce the Hebrew gentlemen to procure a place of worship.”

The members of Emanu-El acted quickly, constructing a synagogue in 1876 on land owned by the B’nai B’rith lodge. Costing $15,000, the Moorish revival synagogue included classrooms and a meeting space for local Jewish lodges. Initially, the classrooms housed a secular, non-sectarian elementary school during the week, while Alice Levy ran the Sunday school for the congregation. From the outset, Emanu-El was Reform in orientation, voting to adopt Isaac Mayer Wise’s Minhag America prayer book in 1874. In 1875, they hired Aaron Suhler as their first full-time rabbi. For their first decade or so, Emanu-El had several short-term rabbis. Rabbi Edward Chapman led the congregation from 1885 to 1897. In 1882, the congregation experienced a brief schism when a group of disgruntled members created Congregation Ahavas Shalom. By 1884, the breakaway group had returned to Emanu-El, and the congregation grew steadily. Soon they outgrew their building, leading Emanu-El’s 100 members to construct a new temple on South Ervay Street in 1899. They only stayed in this new temple for 18 years, as the congregation doubled during this period. In 1917, they built a new larger synagogue, which featured a gym, on South Boulevard.

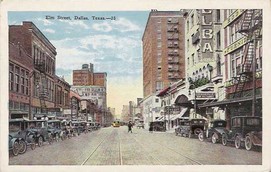

Elm Street

Elm Street

In the late 19th century, growing numbers of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe moved to Dallas, with many opening small retail stores and pawn shops on Elm Street in the predominately African American area around the railroad depot known as “Deep Ellum.” Many of these Jews initially lived above their stores. It was on Elm Street that these newly arrived immigrants created their own Orthodox congregation, Shaareth Israel (later changed to Shearith Israel) in 1884. Josiah Emin and L. Levy met at Michael Wasserman’s store on Elm Street to discuss the founding of a congregation; previously, the city’s small number of Orthodox Jews had met together informally to worship on the High Holidays. Wasserman acquired a Torah for the small group, which numbered no more than 12 men. The young congregation held weekly services on the second floor above Bradford’s Grocery Store. In 1886, Shaareth Israel was officially chartered with 20 members. Most of these charter members were recent arrivals in Dallas; only one of the 20, congregation president Sam Iralson, lived in Dallas in 1880. Several of these founding members, including Michael Wasserman and Josiah Emin, had left Russia for the United States in 1881 or 1882, most likely due to the wave of pogroms that targeted Jews there.

Under the leadership of Charles Goldstein, Shaareth Israel built a red brick synagogue on Jackson Street in 1892. The following year, the congregation hired its first full-time rabbi, Nehemiah Mosesshon, who led Shaareth Israel for the next five years. By 1900, Shaareth Israel had 55 members. The congregation grew tremendously in the early 20th century, reaching 150 members by 1919. While the congregation was nominally Orthodox, it began to adjust its practices to reflect the assimilation of its members, introducing mixed-gender seating. In 1913, they hired Louis Epstein, a graduate of the Conservative Jewish Theological Seminary, as their rabbi.

Rabbi Epstein introduced such innovations as a modern Sunday school, Friday night services, and confirmation. Although Epstein only stayed for two years, the changes he introduced fit the members of Shaareth Israel, whom the congregation’s president Louis Kleinman described in 1913 as “comparatively well-to-do Americanized Jews.”

Rabbi Epstein introduced such innovations as a modern Sunday school, Friday night services, and confirmation. Although Epstein only stayed for two years, the changes he introduced fit the members of Shaareth Israel, whom the congregation’s president Louis Kleinman described in 1913 as “comparatively well-to-do Americanized Jews.”

The 1908 Texas Zionist Association Convention

The 1908 Texas Zionist Association Convention was held at Shearith Israel.

Photo courtesy of Fort Worth Jewish Archives.

Other Eastern European Jewish immigrants settled in the area of north Dallas known as Goose Valley. Bounded by railroad tracks, Goose Valley offered both cheap housing and economic opportunity. Many of these Polish and Russian Jews opened small stores in the neighborhood, which became Dallas’s version of a Jewish immigrant enclave. In 1890, a group of 11 Goose Valley Jews established the Orthodox congregation Tiferet Israel. For its first three years the congregation met at the home of member Jake Donosky. In 1893, Tiferet Israel bought a house, which it converted into a small synagogue. By 1900, the congregation had 35 members. Two years later, they tore down the house and built a new synagogue on the same lot. Tiferet Israel was strictly Orthodox, holding daily worship services; their new synagogue included a mikvah (Jewish ritual bath) and separate seating for men and women. From 1900 to 1906, Tiferet Israel shared a rabbi with Shearith Israel, but then hired their own spiritual leader, David Bernstein. When he died in 1919, Bernstein was replaced by Meyer Shwiff, who led the congregation as rabbi, cantor, shochet (kosher butcher) and mohel for the next 12 years.

Titche-Goettinger & Co.

Titche-Goettinger & Co.

Jewish Businesses in Dallas

Dallas Jews concentrated in retail trade. By 1900, Jews owned 10 grocery stores, 14 dry goods stores, 25 clothing stores, 8 saloons, 6 tobacco businesses, and 9 tailoring shops. Only a few Dallas Jews worked in the professions at the time; there were four Jewish lawyers in Dallas in 1900. Other Jews were involved in the regional cotton trade. Three Jews served as president of the Dallas Cotton Exchange. Joseph Linz and his two brothers opened a jewelry store in Dallas in 1891 and became a quick success. Only eight years after arriving in the city, Jos. Linz and Bros. constructed the tallest building in Dallas to house their growing business.

Perhaps the best known Dallas Jews were the merchant princes who built several of the city’s large department stores. Prussian-born Adolph Harris, who had opened a Dallas branch of a Galveston store in 1887, bought out his partners in 1892 and renamed the store A. Harris & Co. It soon grew into a large, successful department store. When Harris died in 1912, Arthur Kramer took over as president. A. Harris & Co. was sold to Federated Stores in 1961, which merged it with Sangers. Across the street from A. Harris & Co., Ed Titche and Max Goettinger opened their own store in 1902. Titche-Goettinger & Co. grew quickly, moving into a 12-story building in 1911. The large store had 600 employees in 1929, when the partners, neither of whom had children, decided to retire and sell the business. The new owners kept the store’s name, which remained in business until 1979.

The city’s most famous store was Neiman-Marcus, which came to symbolize Dallas-style luxury and opulence. Born in Louisville, Herbert Marcus moved to Dallas in 1897 and worked as a clerk at the Sanger Brothers store. His sister Carrie followed him two years later, and went to work for A. Harris & Co.; Carrie later married Abraham Lincoln (Al) Neiman. In 1907, the three of them opened Neiman-Marcus, a high fashion, ready-to-wear women’s clothing store. Specializing in the latest New York fashions, the store was a quick success and soon moved to a much larger space. Herbert’s sons later joined the business. Stanley Marcus became president of the company after his father Herbert, who served as store president for 43 years, died in 1950. Neiman-Marcus thrived along with the east Texas oil boom as Stanley built the store into the institution that it is today. Stanley’s son, Richard, later took over the business, though he left after Neiman-Marcus was sold to General Cinemas in 1989. While the name Neiman-Marcus continues today in shopping malls around the country, the Marcus and Neiman families are no longer involved.

In the early 20th century, Dallas developed its own garment manufacturing industry, fueled by cheap labor and a non-unionized workforce. Soon, the Dallas Market developed, in which store buyers from around the region would come to the Dallas convention to order their merchandise for the upcoming season. By the 1950s, Dallas was the third largest producer of clothing in the U.S. Jews, often with ties to the New York garment industry, helped lead the way. Leo Fife and Esir Aronofsky opened a tailor shop together in the Deep Ellum district in 1912. By the 1940s, they had 50 employees, and sold their own suits, which were made on the third floor of their building. August Lorch began as a peddler based out of Dallas in 1892. In 1909, he established the Lorch Manufacturing Company, which initially sold ready-made women’s clothing from New York. Soon, his company began to make the clothes themselves, producing numerous brands of ladies and girls dresses. August’s son Lester took over the business in 1939. The Lorch Manufacturing Company remained in the family until it was sold in 1989.

One of the most unique Dallas-based clothing companies started after Elsie Frankfurt was appalled one day by the clothes worn by her pregnant sister Edna. A recent graduate of SMU’s School of Design, Elsie was convinced she could make more flattering clothes for pregnant women. Along with their other sister Louise, the three created Page Boy, Inc. in 1938, which specialized in manufacturing stylish maternity dresses and suits. Page Boy grew into a successful national business. Ed Byer and Harry Rolnick founded Byer-Rolnick in 1927, which eventually became one of the country’s largest producers of men’s hats. Known for their Resistol brand hats, Byer-Rolnick manufactured the famous ranch hat worn by President Lyndon Johnson. When Ed Byer died, he left the bulk of his estate to the United Jewish Appeal; at the time, it was the largest gift ever received by the UJA.

Dallas Jews concentrated in retail trade. By 1900, Jews owned 10 grocery stores, 14 dry goods stores, 25 clothing stores, 8 saloons, 6 tobacco businesses, and 9 tailoring shops. Only a few Dallas Jews worked in the professions at the time; there were four Jewish lawyers in Dallas in 1900. Other Jews were involved in the regional cotton trade. Three Jews served as president of the Dallas Cotton Exchange. Joseph Linz and his two brothers opened a jewelry store in Dallas in 1891 and became a quick success. Only eight years after arriving in the city, Jos. Linz and Bros. constructed the tallest building in Dallas to house their growing business.

Perhaps the best known Dallas Jews were the merchant princes who built several of the city’s large department stores. Prussian-born Adolph Harris, who had opened a Dallas branch of a Galveston store in 1887, bought out his partners in 1892 and renamed the store A. Harris & Co. It soon grew into a large, successful department store. When Harris died in 1912, Arthur Kramer took over as president. A. Harris & Co. was sold to Federated Stores in 1961, which merged it with Sangers. Across the street from A. Harris & Co., Ed Titche and Max Goettinger opened their own store in 1902. Titche-Goettinger & Co. grew quickly, moving into a 12-story building in 1911. The large store had 600 employees in 1929, when the partners, neither of whom had children, decided to retire and sell the business. The new owners kept the store’s name, which remained in business until 1979.

The city’s most famous store was Neiman-Marcus, which came to symbolize Dallas-style luxury and opulence. Born in Louisville, Herbert Marcus moved to Dallas in 1897 and worked as a clerk at the Sanger Brothers store. His sister Carrie followed him two years later, and went to work for A. Harris & Co.; Carrie later married Abraham Lincoln (Al) Neiman. In 1907, the three of them opened Neiman-Marcus, a high fashion, ready-to-wear women’s clothing store. Specializing in the latest New York fashions, the store was a quick success and soon moved to a much larger space. Herbert’s sons later joined the business. Stanley Marcus became president of the company after his father Herbert, who served as store president for 43 years, died in 1950. Neiman-Marcus thrived along with the east Texas oil boom as Stanley built the store into the institution that it is today. Stanley’s son, Richard, later took over the business, though he left after Neiman-Marcus was sold to General Cinemas in 1989. While the name Neiman-Marcus continues today in shopping malls around the country, the Marcus and Neiman families are no longer involved.

In the early 20th century, Dallas developed its own garment manufacturing industry, fueled by cheap labor and a non-unionized workforce. Soon, the Dallas Market developed, in which store buyers from around the region would come to the Dallas convention to order their merchandise for the upcoming season. By the 1950s, Dallas was the third largest producer of clothing in the U.S. Jews, often with ties to the New York garment industry, helped lead the way. Leo Fife and Esir Aronofsky opened a tailor shop together in the Deep Ellum district in 1912. By the 1940s, they had 50 employees, and sold their own suits, which were made on the third floor of their building. August Lorch began as a peddler based out of Dallas in 1892. In 1909, he established the Lorch Manufacturing Company, which initially sold ready-made women’s clothing from New York. Soon, his company began to make the clothes themselves, producing numerous brands of ladies and girls dresses. August’s son Lester took over the business in 1939. The Lorch Manufacturing Company remained in the family until it was sold in 1989.

One of the most unique Dallas-based clothing companies started after Elsie Frankfurt was appalled one day by the clothes worn by her pregnant sister Edna. A recent graduate of SMU’s School of Design, Elsie was convinced she could make more flattering clothes for pregnant women. Along with their other sister Louise, the three created Page Boy, Inc. in 1938, which specialized in manufacturing stylish maternity dresses and suits. Page Boy grew into a successful national business. Ed Byer and Harry Rolnick founded Byer-Rolnick in 1927, which eventually became one of the country’s largest producers of men’s hats. Known for their Resistol brand hats, Byer-Rolnick manufactured the famous ranch hat worn by President Lyndon Johnson. When Ed Byer died, he left the bulk of his estate to the United Jewish Appeal; at the time, it was the largest gift ever received by the UJA.

1936 dedication of Anshe Sphard synagogue.

1936 dedication of Anshe Sphard synagogue. Photo courtesy of

Dallas Jewish Historical Society.

A Growing Community

The Jewish population of Dallas grew steadily in the early 20th century, reaching an estimated 4,000 Jews in 1907. Much of this growth was due to the influx of immigrants from Eastern Europe, who established new Orthodox congregations in the city. In 1906, Jews from Austria and Romania founded Anshe Sphard in the Goose Valley neighborhood. Following the Sephardic rite, the small group met in private homes initially. In 1913, they bought a house which they converted into a synagogue. When most of its members moved out of the neighborhood, the congregation moved to a house in south Dallas. In 1936, the 40 members of Anshe Sphard moved to a new building which had formerly housed a telephone exchange. Known informally as the Roumanishe Shul, Anshe Sphard never had a rabbi or religious school; Charles Kaufman served as lay leader of the congregation for many years. In 1956, the small congregation merged with the much larger Shearith Israel.

The Jewish population of Dallas grew steadily in the early 20th century, reaching an estimated 4,000 Jews in 1907. Much of this growth was due to the influx of immigrants from Eastern Europe, who established new Orthodox congregations in the city. In 1906, Jews from Austria and Romania founded Anshe Sphard in the Goose Valley neighborhood. Following the Sephardic rite, the small group met in private homes initially. In 1913, they bought a house which they converted into a synagogue. When most of its members moved out of the neighborhood, the congregation moved to a house in south Dallas. In 1936, the 40 members of Anshe Sphard moved to a new building which had formerly housed a telephone exchange. Known informally as the Roumanishe Shul, Anshe Sphard never had a rabbi or religious school; Charles Kaufman served as lay leader of the congregation for many years. In 1956, the small congregation merged with the much larger Shearith Israel.

Agudas Achim's 1926 synagogue.

Agudas Achim's 1926 synagogue. Photo courtesty of

Dallas Jewish Historical Society.

In 1925, Orthodox Jews in south Dallas who were unable to walk to Shearith Israel or Anshe Sphard established a new congregation, Agudas Achim. That same year, the group bought a two-story house on Forrest Avenue to use as a synagogue and hired Rabbi Jonathan Abramowitz, who led the congregation for the next 26 years. The young congregation grew quickly, and tore down the house and replaced it with a larger brick building in 1926. In 1939, they constructed a building for their Talmud Torah adjoining the synagogue.

By the 1950s, Agudas Achim, which had earlier peaked at 300 members, was in decline as many members had moved out of the neighborhood. In 1957, they sold their synagogue to a church, but continued to meet in the Talmud Torah building. While the remaining members discussed moving the congregation to north Dallas, in the end they decided to disband. Proceeds from the sale of Agudas Achim’s buildings were given to the city’s first Jewish day school, the Akiba Academy, which was founded in 1962.

When Agudas Achim fired Rabbi Milton Rosen as principal of the Talmud Torah in 1942, a disgruntled group broke away to form Congregation Ohave Shalom with Rosen as their spiritual leader. The group met in a house on South Boulevard. After Rabbi Rosen left in 1944 when the congregation could not afford to pay his salary, Ohave Shalom began to evolve into a Jewish home for the aged. Old men began to live on the second floor of the house, leading services and helping to make a minyan each day. By 1947, 14 men lived in the home. Ohave Shalom showed the need for a Jewish old age home in Dallas. The Dallas Jewish Federation established the Dallas Home for the Jewish Aged, and built the Golden Acres home in 1953. Ohave Shalom donated its building to the new organization.

Despite these new Orthodox congregations, Shearith Israel continued to thrive. In 1920, the congregation dedicated a new larger synagogue across from City Park. At the cornerstone laying ceremony in 1919, Dallas Mayor Frank Wozencraft spoke, calling Shearith Israel “representative of the best in the city.” The Ladies Auxiliary, which had been formed in 1913, helped to raise money for the synagogue, holding a series of 50-cent chicken dinners on Sunday nights and a downtown bazaar in 1917. In 1928, the congregation hired Orthodox rabbi H. Raphael Gold to lead them; he remained at Shearith Israel until 1942. In 1954, Shearith Israel hired Hillel Silverman, a graduate of the Jewish Theological Seminary, to be their rabbi; two years later, they officially joined the Conservative movement.

By the 1950s, Agudas Achim, which had earlier peaked at 300 members, was in decline as many members had moved out of the neighborhood. In 1957, they sold their synagogue to a church, but continued to meet in the Talmud Torah building. While the remaining members discussed moving the congregation to north Dallas, in the end they decided to disband. Proceeds from the sale of Agudas Achim’s buildings were given to the city’s first Jewish day school, the Akiba Academy, which was founded in 1962.

When Agudas Achim fired Rabbi Milton Rosen as principal of the Talmud Torah in 1942, a disgruntled group broke away to form Congregation Ohave Shalom with Rosen as their spiritual leader. The group met in a house on South Boulevard. After Rabbi Rosen left in 1944 when the congregation could not afford to pay his salary, Ohave Shalom began to evolve into a Jewish home for the aged. Old men began to live on the second floor of the house, leading services and helping to make a minyan each day. By 1947, 14 men lived in the home. Ohave Shalom showed the need for a Jewish old age home in Dallas. The Dallas Jewish Federation established the Dallas Home for the Jewish Aged, and built the Golden Acres home in 1953. Ohave Shalom donated its building to the new organization.

Despite these new Orthodox congregations, Shearith Israel continued to thrive. In 1920, the congregation dedicated a new larger synagogue across from City Park. At the cornerstone laying ceremony in 1919, Dallas Mayor Frank Wozencraft spoke, calling Shearith Israel “representative of the best in the city.” The Ladies Auxiliary, which had been formed in 1913, helped to raise money for the synagogue, holding a series of 50-cent chicken dinners on Sunday nights and a downtown bazaar in 1917. In 1928, the congregation hired Orthodox rabbi H. Raphael Gold to lead them; he remained at Shearith Israel until 1942. In 1954, Shearith Israel hired Hillel Silverman, a graduate of the Jewish Theological Seminary, to be their rabbi; two years later, they officially joined the Conservative movement.

Shearith Israel's second synagogue, dedicated in 1920

Shearith Israel's second synagogue, dedicated in 1920

Jewish Organizations in Dallas

In addition to congregations, Dallas Jews established a wide array of other Jewish organizations. In 1879, Dallas Jews created a Young Men’s Hebrew Association, which initially met in the B’nai B’rith hall located at Temple Emanu-El. In 1887, the group built its own clubhouse, though they were unable to pay the mortgage. In 1890, the YMHA disbanded and sold its building to a Jewish social club, the Phoenix Club. Not until 1919 did the YMHA reorganize in Dallas. This time they were the beneficiary of another struggling Jewish organization, when the Parkview Club gave its building to the YMHA if they agreed to take on the mortgage. The YMHA moved in and built a gym, which hosted many of their social and athletic activities. In 1924, the Dallas Jewish Federation of Social Services, which had been founded in 1911, took the YMHA under its wing, moving its offices to the Y. In 1927, the YMHA deeded its building to the federation and changed its name to the Jewish Community Center.

In 1898, a group of women founded a chapter of the National Council of Jewish Women, although it became inactive a few years later. The rising number of immigrants living in Dallas prompted the group to reform in 1913. The Dallas NCJW chapter opened a free clinic and instituted a penny lunch and free milk program at a local school in a poor immigrant neighborhood. Council members made the lunches and sold them to students for a penny each. In 1918, the Dallas Board of Education took over the school lunch program and expanded it to the other schools in the city. Over the years, Jewish women in Dallas have been very involved in charity and social work.

In addition to congregations, Dallas Jews established a wide array of other Jewish organizations. In 1879, Dallas Jews created a Young Men’s Hebrew Association, which initially met in the B’nai B’rith hall located at Temple Emanu-El. In 1887, the group built its own clubhouse, though they were unable to pay the mortgage. In 1890, the YMHA disbanded and sold its building to a Jewish social club, the Phoenix Club. Not until 1919 did the YMHA reorganize in Dallas. This time they were the beneficiary of another struggling Jewish organization, when the Parkview Club gave its building to the YMHA if they agreed to take on the mortgage. The YMHA moved in and built a gym, which hosted many of their social and athletic activities. In 1924, the Dallas Jewish Federation of Social Services, which had been founded in 1911, took the YMHA under its wing, moving its offices to the Y. In 1927, the YMHA deeded its building to the federation and changed its name to the Jewish Community Center.

In 1898, a group of women founded a chapter of the National Council of Jewish Women, although it became inactive a few years later. The rising number of immigrants living in Dallas prompted the group to reform in 1913. The Dallas NCJW chapter opened a free clinic and instituted a penny lunch and free milk program at a local school in a poor immigrant neighborhood. Council members made the lunches and sold them to students for a penny each. In 1918, the Dallas Board of Education took over the school lunch program and expanded it to the other schools in the city. Over the years, Jewish women in Dallas have been very involved in charity and social work.

Hebrew School students c. 1930.

Hebrew School students c. 1930. Photo courtesy of

Dallas Jewish Historical Society.

For observant Jews, religious education centered around the community Hebrew School, established in 1924; by 1926, 235 children received instruction in Judaism and Hebrew language at the school. Although not affiliated with any congregation, the Hebrew School was largely supported by the members of Shearith Israel. Most of the city’s Orthodox congregations did not have Hebrew schools, using the community school instead. The school, run by Jacob Levin from 1929 to 1946, owned a bus which would pick up students after school four days a week. In 1939, the school moved to a larger house, but the school struggled in the 1940s. In 1946, the school merged with Agudas Achim’s Talmud Torah. When Shearith Israel established its own Hebrew school in 1956, the community school finally closed for good; each congregation was now responsible for the instruction of its own children.

By the 1920s, Jews were concentrated in south Dallas, which became the physical center of the Dallas Jewish community. By the 1930s, all of the city’s synagogues were located in south Dallas, as were such institutions as the Workmen’s Circle School and the Hebrew School. Most of the city’s Jews lived in the neighborhood, while many Jewish-owned businesses lined its commercial thoroughfares. By the 1940s, Jews had begun to leave south Dallas for more suburban neighborhoods in the northern part of the city. In the 1950s, the Jewish institutions followed their members. Temple Emanu-El moved northward in 1955 with Shearith Israel and Tifereth Israel building new homes in north Dallas a year later. The Jewish Community Center bought land on Northaven Road in 1954, and dedicated a new building there eight years later. Due to the later construction of freeways through the area, little physical vestige of the Jewish enclave of south Dallas remains standing today.

By the 1920s, Jews were concentrated in south Dallas, which became the physical center of the Dallas Jewish community. By the 1930s, all of the city’s synagogues were located in south Dallas, as were such institutions as the Workmen’s Circle School and the Hebrew School. Most of the city’s Jews lived in the neighborhood, while many Jewish-owned businesses lined its commercial thoroughfares. By the 1940s, Jews had begun to leave south Dallas for more suburban neighborhoods in the northern part of the city. In the 1950s, the Jewish institutions followed their members. Temple Emanu-El moved northward in 1955 with Shearith Israel and Tifereth Israel building new homes in north Dallas a year later. The Jewish Community Center bought land on Northaven Road in 1954, and dedicated a new building there eight years later. Due to the later construction of freeways through the area, little physical vestige of the Jewish enclave of south Dallas remains standing today.

Herbert Marcus.

Herbert Marcus. Photo courtesy of

Dallas Jewish Historical Society

Civic Engagement

Generally, Jews enjoyed tremendous acceptance in Dallas. While they were still excluded from certain elite clubs, prominent Jews were welcomed into the city’s power structure as they worked to build the city into an economic and cultural center. Jews became major patrons of the arts in Dallas. Arthur Kramer, of A.H. Harris & Co., founded the Dallas Grand Opera Association and served as president of the Dallas Symphony Orchestra. Ed Titche served on the board of the State Fair Association and of several local hospitals. Titche helped to found the local chapter of the Red Cross and donated a large mansion to the chapter in 1943 for use as a headquarters. The Marcus family was very philanthropic in Dallas. Herbert Marcus helped to establish Southern Methodist University. When Herbert died, the Texas Legislature passed a resolution honoring him. His wife Minnie was a founder of the Dallas Garden Center and worked to beautify the city. Louis Jules Hexter, a local lawyer, helped to found the Dallas Little Theater in the 1920s; he later founded the Dallas Negro Players theater group. John Rosenfield served as the theater and culture critic for the Dallas Morning News from 1925 until his death in 1966; Rosenfield was an important voice for the arts in Dallas.

Generally, Jews enjoyed tremendous acceptance in Dallas. While they were still excluded from certain elite clubs, prominent Jews were welcomed into the city’s power structure as they worked to build the city into an economic and cultural center. Jews became major patrons of the arts in Dallas. Arthur Kramer, of A.H. Harris & Co., founded the Dallas Grand Opera Association and served as president of the Dallas Symphony Orchestra. Ed Titche served on the board of the State Fair Association and of several local hospitals. Titche helped to found the local chapter of the Red Cross and donated a large mansion to the chapter in 1943 for use as a headquarters. The Marcus family was very philanthropic in Dallas. Herbert Marcus helped to establish Southern Methodist University. When Herbert died, the Texas Legislature passed a resolution honoring him. His wife Minnie was a founder of the Dallas Garden Center and worked to beautify the city. Louis Jules Hexter, a local lawyer, helped to found the Dallas Little Theater in the 1920s; he later founded the Dallas Negro Players theater group. John Rosenfield served as the theater and culture critic for the Dallas Morning News from 1925 until his death in 1966; Rosenfield was an important voice for the arts in Dallas.

Julius Schepps.

Julius Schepps. Photo courtesy of the

Dallas Jewish Historical Society

Dallas was controlled by its prominent businessmen. The Dallas Citizens Council, formed in conjunction with the Texas centennial celebration in 1936 and made up of 22 economic and civic leaders, essentially ran the city in the mid-20th century. Two Jews, Julius Schepps and Fred Florence, were longtime members of the council, while Stanley Marcus of Neiman-Marcus was also part of the council in later years. Schepps, who moved to Dallas as a boy in 1901, made his fortune in the wholesale liquor and insurance business. Involved in many local charities, Schepps was also active in the Jewish community, serving as heads of the Jewish Federation and the Dallas Home for the Aged. When the JCC built a new facility in 1962, they named it after Schepps. He spent 18 years on the Dallas Park Board, and was named Dallas’s most outstanding citizen in 1954. To honor his civic contributions, a section of Interstate 45 in Dallas was named the Julius Schepps Freeway. Fred Florence was the longtime president of Dallas’ powerful Republic National Bank, leading the institution from 1929 to 1957. Both Schepps and Florence helped to bring the Texas Centennial Celebration to the city in 1936, which helped to put the growing city on the national map.

The Civil Rights Era

According to historian Bryan Stone, a handful of prominent Jews played a leading role in integrating the city during the civil rights era. Certainly, the large Jewish-owned department stores in town enforced the city’s segregation laws for decades. But once the federal courts enforced integration, Jewish merchants were quick to change. Stanley Marcus integrated Neiman-Marcus in 1961, and even ordered that black sales clerks be hired. Sam Bloom, the head of a large local advertising agency, put together a public relations campaign designed to convince white Dallasites to accept integration without the massive resistance that had wracked other Southern cities. His short film, “Dallas at the Crossroads,” contrasted the violence of the Little Rock school integration crisis with tranquil images of Dallas life. In the film, which was shown to civic and church groups around the city, Bloom made the case that resisting integration would harm Dallas’s reputation and economy. Julius Schepps was put in charge of the Citizens Council Committee to Work with Negro Leaders, which worked quietly to integrate schools and public facilities in the city. The committee deliberately avoided publicity for their work, which brought about the peaceful integration of the city.

Among the loudest voices for social and racial justice in Dallas was Rabbi Levi Olan, spiritual leader of Temple Emanu-El. Historian Hollace Weiner has called Olan “Dallas’s civic conscience.” Olan came to Dallas in 1949, replacing the Reform temple’s longtime rabbi David Lefkowitz, who had fought against the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s. Like his predecessor, Olan had a weekly radio show on Sunday mornings, in which he addressed such controversial topics as civil rights from a Jewish perspective. After the Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education, Rabbi Olan helped to found Dallas Citizens for Peaceful Integration. Olan regularly spoke at black churches in town and sat on the stage during a local rally in 1963 in which Martin Luther King, Jr. spoke. While Olan received criticism for his outspoken opinions on civil rights and other issues, he garnered tremendous respect for his integrity and moral authority; in 1962, he was appointed to the University of Texas Board of Regents. As head of the Dallas Housing Authority, Olan was well aware of the problems that blacks in public housing faced, especially the children, who often started first grade already behind other students academically. There was no public preschool or kindergarten program in the city at the time. Under Olan’s leadership, Emanu-El opened the Rhoads Terrace Housing Project Pre-School in 1965. Women from the temple made and served lunch to the preschoolers and volunteered in their classrooms. Olan pushed the city of Dallas to establish free kindergarten, which they eventually did in 1971.

According to historian Bryan Stone, a handful of prominent Jews played a leading role in integrating the city during the civil rights era. Certainly, the large Jewish-owned department stores in town enforced the city’s segregation laws for decades. But once the federal courts enforced integration, Jewish merchants were quick to change. Stanley Marcus integrated Neiman-Marcus in 1961, and even ordered that black sales clerks be hired. Sam Bloom, the head of a large local advertising agency, put together a public relations campaign designed to convince white Dallasites to accept integration without the massive resistance that had wracked other Southern cities. His short film, “Dallas at the Crossroads,” contrasted the violence of the Little Rock school integration crisis with tranquil images of Dallas life. In the film, which was shown to civic and church groups around the city, Bloom made the case that resisting integration would harm Dallas’s reputation and economy. Julius Schepps was put in charge of the Citizens Council Committee to Work with Negro Leaders, which worked quietly to integrate schools and public facilities in the city. The committee deliberately avoided publicity for their work, which brought about the peaceful integration of the city.

Among the loudest voices for social and racial justice in Dallas was Rabbi Levi Olan, spiritual leader of Temple Emanu-El. Historian Hollace Weiner has called Olan “Dallas’s civic conscience.” Olan came to Dallas in 1949, replacing the Reform temple’s longtime rabbi David Lefkowitz, who had fought against the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s. Like his predecessor, Olan had a weekly radio show on Sunday mornings, in which he addressed such controversial topics as civil rights from a Jewish perspective. After the Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education, Rabbi Olan helped to found Dallas Citizens for Peaceful Integration. Olan regularly spoke at black churches in town and sat on the stage during a local rally in 1963 in which Martin Luther King, Jr. spoke. While Olan received criticism for his outspoken opinions on civil rights and other issues, he garnered tremendous respect for his integrity and moral authority; in 1962, he was appointed to the University of Texas Board of Regents. As head of the Dallas Housing Authority, Olan was well aware of the problems that blacks in public housing faced, especially the children, who often started first grade already behind other students academically. There was no public preschool or kindergarten program in the city at the time. Under Olan’s leadership, Emanu-El opened the Rhoads Terrace Housing Project Pre-School in 1965. Women from the temple made and served lunch to the preschoolers and volunteered in their classrooms. Olan pushed the city of Dallas to establish free kindergarten, which they eventually did in 1971.

Annette Strauss

Annette Strauss

Jewish Politicians in Dallas

This prominent civic role was not new for Dallas Jews. Going back to 1873, when Alex Sanger was elected alderman, Jews have long been involved in local politics. Several Dallas Jews have served as aldermen and councilmen over the years. Sigmund Loeb served as alderman from 1883 to 1892. In recent decades, a growing number of Dallas Jews have been elected to office. Joe Golman represented the city in the Texas legislature from 1969 to 1973. Al Granoff and Steve Wolens represented Dallas in the Texas House of Representatives for many years in the 1980s and 90s. Florence Shapiro represented the northern suburb of Plano in the state senate from 1993 to 2013, after serving as mayor of the town. Congressman Martin Frost represented Dallas in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1979 to 2004. Three Jews have served as mayor of Dallas, all of whom were women. Adlene Harrison, who was a city councilwoman, became interim mayor in 1976 when the sitting mayor resigned. In 1987, Annette Strauss, a longtime civic leader, was elected to her first of two terms as mayor. In 2002, Laura Miller, who started out as a local investigative reporter, was elected mayor of Dallas, serving until 2007.

Perhaps the most politically influential Dallas Jews never served in elected office. Robert Strauss moved to Dallas as a young lawyer in the 1940s. He soon got involved in Democratic Party politics as an advisor and fundraiser to Lyndon Johnson and John Connally. Strauss later served as chairman of the national Democratic Party from 1972 to 1977. A political centrist, Strauss was appointed ambassador to the Soviet Union by President George Bush in 1991.Hermine Tobolowsky was a lawyer who drafted and led the fight to pass the Equal Legal Rights Amendment in Texas. Historically, married women in Texas had no legal rights independent of their husband. Tobolowsky spent 13 years lobbying and cajoling the Texas legislature to grant legal equality to married women. Finally, both houses of the legislature passed the constitutional amendment in 1971, and it was overwhelmingly approved by Texas voters the following year. Tobolowsky was elected to the Texas Women’s Hall of Fame in 1986.

This prominent civic role was not new for Dallas Jews. Going back to 1873, when Alex Sanger was elected alderman, Jews have long been involved in local politics. Several Dallas Jews have served as aldermen and councilmen over the years. Sigmund Loeb served as alderman from 1883 to 1892. In recent decades, a growing number of Dallas Jews have been elected to office. Joe Golman represented the city in the Texas legislature from 1969 to 1973. Al Granoff and Steve Wolens represented Dallas in the Texas House of Representatives for many years in the 1980s and 90s. Florence Shapiro represented the northern suburb of Plano in the state senate from 1993 to 2013, after serving as mayor of the town. Congressman Martin Frost represented Dallas in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1979 to 2004. Three Jews have served as mayor of Dallas, all of whom were women. Adlene Harrison, who was a city councilwoman, became interim mayor in 1976 when the sitting mayor resigned. In 1987, Annette Strauss, a longtime civic leader, was elected to her first of two terms as mayor. In 2002, Laura Miller, who started out as a local investigative reporter, was elected mayor of Dallas, serving until 2007.

Perhaps the most politically influential Dallas Jews never served in elected office. Robert Strauss moved to Dallas as a young lawyer in the 1940s. He soon got involved in Democratic Party politics as an advisor and fundraiser to Lyndon Johnson and John Connally. Strauss later served as chairman of the national Democratic Party from 1972 to 1977. A political centrist, Strauss was appointed ambassador to the Soviet Union by President George Bush in 1991.Hermine Tobolowsky was a lawyer who drafted and led the fight to pass the Equal Legal Rights Amendment in Texas. Historically, married women in Texas had no legal rights independent of their husband. Tobolowsky spent 13 years lobbying and cajoling the Texas legislature to grant legal equality to married women. Finally, both houses of the legislature passed the constitutional amendment in 1971, and it was overwhelmingly approved by Texas voters the following year. Tobolowsky was elected to the Texas Women’s Hall of Fame in 1986.

The Jewish Community in Dallas Today

Temple Shalom. Photo courtesy of Julian Preisler

Temple Shalom. Photo courtesy of Julian Preisler

The Dallas Jewish community has changed significantly in the last several decades. The great Jewish-owned department stores have either closed or been sold to national chains. E.M. Kahn & Co. was sold to a New York firm in 1969, which mismanaged the stores until they declared bankruptcy and closed in 1979. The Federated Department Store chain bought Sanger’s in 1951 and later merged it with A. Harris & Co. In 1987, Federated changed the name of all of these stores to Foley’s, casting aside brand names that had reigned in Dallas for over a century. As in the rest of the sunbelt South, the Dallas Jewish community has largely moved out of the retail business and into the professions and the corporate world. In a 1939 study of the Dallas Jewish population, 49% of adults worked in retail trade, while only 11% were professionals. By 1988, 29% were professionals while 19% were corporate executives or managers; only 6% were business owners.

Despite these changes, the Dallas Jewish community exploded in the decades after World War II as the city emerged from the oil boom as one of America’s largest cities. While few Dallas Jews were directly involved in oil, they benefited from the remarkable prosperity it brought to the city. In 1948, Dallas had approximately 10,000 Jews; by 1960, their numbers had grown to almost 18,000. By 1988, 38,000 Jews lived in Dallas; in 2000, an estimated 47,000 Jews lived in the city and its suburbs. In a 1988 population study, the Dallas Jewish Federation found that 63% of adult Dallas Jews had moved to the city in the previous 20 years. This population growth had a huge impact on the city’s Jewish congregations. Shearith Israel went from 600 families in 1954 to over 1,000 by the end of the 1950s. By 1998, Shearith Israel had 1700 families. Temple Emanu-El grew from 823 members in 1945 to over 2000 in 1965; in 2010, it had over 2,500 members.

Another sign of the Dallas Jewish community’s growth is the spate of new congregations founded in the city over the last few decades. Perhaps to alleviate the pressures on his own growing congregation, Rabbi Levi Olan of Emanu-El helped to establish a second Reform congregation in Dallas in 1965. Named Temple Shalom, the group initially met at the Southern Methodist University Chapel. Shearith Israel lent them a Torah to use. The congregation, made up of primarily young families, met at a Methodist Church for six years; Rabbi Saul Besser was hired in 1969. In 1974, Temple Shalom built a synagogue on Hillcrest Road. Temple Shalom grew from 210 families in 1970 to over 950 in 1995. Several of these new congregations were founded in the suburbs north of the city. Jews in Richardson founded the Conservative congregation Beth Torah in 1974, and built a synagogue in 1982. Anshei Emet, founded in 1979, built a synagogue in Plano in 1996. Carrollton Jews founded Ner Tamid in 1984; starting out as Conservative, the congregation joined the Reform movement in 1989. In recent years, several Orthodox congregations have been founded, including Young Israel, Ohev Shalom, and Shaare Tefilla. Congregation Beth El Binah, founded in 1985, caters to LGBTQ Jews.

By the 21st century, Dallas’s Jewish community offered congregational options and educational resources on par with any other city in America. The Jewish community remains, as it always has been, an important part of the city.

Despite these changes, the Dallas Jewish community exploded in the decades after World War II as the city emerged from the oil boom as one of America’s largest cities. While few Dallas Jews were directly involved in oil, they benefited from the remarkable prosperity it brought to the city. In 1948, Dallas had approximately 10,000 Jews; by 1960, their numbers had grown to almost 18,000. By 1988, 38,000 Jews lived in Dallas; in 2000, an estimated 47,000 Jews lived in the city and its suburbs. In a 1988 population study, the Dallas Jewish Federation found that 63% of adult Dallas Jews had moved to the city in the previous 20 years. This population growth had a huge impact on the city’s Jewish congregations. Shearith Israel went from 600 families in 1954 to over 1,000 by the end of the 1950s. By 1998, Shearith Israel had 1700 families. Temple Emanu-El grew from 823 members in 1945 to over 2000 in 1965; in 2010, it had over 2,500 members.

Another sign of the Dallas Jewish community’s growth is the spate of new congregations founded in the city over the last few decades. Perhaps to alleviate the pressures on his own growing congregation, Rabbi Levi Olan of Emanu-El helped to establish a second Reform congregation in Dallas in 1965. Named Temple Shalom, the group initially met at the Southern Methodist University Chapel. Shearith Israel lent them a Torah to use. The congregation, made up of primarily young families, met at a Methodist Church for six years; Rabbi Saul Besser was hired in 1969. In 1974, Temple Shalom built a synagogue on Hillcrest Road. Temple Shalom grew from 210 families in 1970 to over 950 in 1995. Several of these new congregations were founded in the suburbs north of the city. Jews in Richardson founded the Conservative congregation Beth Torah in 1974, and built a synagogue in 1982. Anshei Emet, founded in 1979, built a synagogue in Plano in 1996. Carrollton Jews founded Ner Tamid in 1984; starting out as Conservative, the congregation joined the Reform movement in 1989. In recent years, several Orthodox congregations have been founded, including Young Israel, Ohev Shalom, and Shaare Tefilla. Congregation Beth El Binah, founded in 1985, caters to LGBTQ Jews.

By the 21st century, Dallas’s Jewish community offered congregational options and educational resources on par with any other city in America. The Jewish community remains, as it always has been, an important part of the city.

Sources

Biderman, Rose G. They Came to Stay: The Story of the Jews of Dallas, 1870-1997 (Austin, TX: Eakin Press, 2002).