Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Florida

Overview >> Florida

Florida postcard. State Archives of Florida.

Florida postcard. State Archives of Florida.

Florida occupies an odd place in the sub-field of southern Jewish history. Until the 20th century, it lagged behind several other southern states in terms of Jewish development, but, since World War II, South Florida (Miami-Dade, Broward, and Palm Beach Counties) has emerged as the third largest Jewish center in the nation and the sixth largest in the world. The divergent trajectory of the Miami-Palm Beach corridor since 1950 belies a longer history of the state that mirrors the broad themes of southern history since the beginnings of European settlement: displacement of American Indians, introduction of plantation agriculture, racial stratification and segregation, and the relatively late arrival of industrialization and urbanization. Similarly, much of Florida’s Jewish history typifies the Jewish experience in the South, while particular aspects of that history could not have occurred anywhere else in the region.

Colonial Period

Following the arrival of Ponce de Leon in Florida in 1513, Spain claimed the peninsula as a colonial possession until 1821, with a brief period of British rule from 1763 to 1783. Consequently, any Jews who settled in Florida during the 16th or 17th centuries did so as Crypto-Jews or Conversos. Although some historians have speculated on the presence of such Jewish settlers in the early development of St. Augustine, Florida, the available evidence remains inconclusive, and the Spanish claim on Florida did dampen the development of a Jewish community into the 19th century.

The first confirmed Jewish settlers in Florida moved to Pensacola in 1763. When Spain ceded Florida to Britain under the Treaty of Paris in 1763, New Orleans passed from French to Spanish control. New Orleans Jews including Joseph de Palacios, Samuel Israel, Alexander Solomons, and Isaac Monsanto soon moved east to avoid the discriminatory policies of Spanish rule. These early settlers and other arrivals from the Caribbean and the colonial South made their livings as merchants and landowners, and they maintained familial and business connections with similar Jewish colonists in other port cities. Several of those first Pensacola Jews left Florida when Spain regained control in 1783, but other Jews moved to Florida during the same period. Still, Florida Jews did not have the numbers or social standing to establish organized congregations until well after the United States purchased the peninsula in 1821.

The first confirmed Jewish settlers in Florida moved to Pensacola in 1763. When Spain ceded Florida to Britain under the Treaty of Paris in 1763, New Orleans passed from French to Spanish control. New Orleans Jews including Joseph de Palacios, Samuel Israel, Alexander Solomons, and Isaac Monsanto soon moved east to avoid the discriminatory policies of Spanish rule. These early settlers and other arrivals from the Caribbean and the colonial South made their livings as merchants and landowners, and they maintained familial and business connections with similar Jewish colonists in other port cities. Several of those first Pensacola Jews left Florida when Spain regained control in 1783, but other Jews moved to Florida during the same period. Still, Florida Jews did not have the numbers or social standing to establish organized congregations until well after the United States purchased the peninsula in 1821.

After 1821

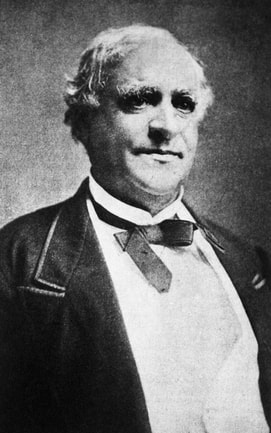

David L. Yulee, son of Moses Levy, served 12 years in the U.S. Senate. State Archives of Florida.

David L. Yulee, son of Moses Levy, served 12 years in the U.S. Senate. State Archives of Florida.

The beginning of US rule in Florida spurred a period of investment and speculation in the territory, as well as the end of anti-Jewish policies. Moses Levy, a Moroccan-born Jew who had lived in St. Thomas and Cuba, purchased a huge swath of land around Micanopy and attempted to establish a utopian sugar and fruit plantation that would provide refuge to European Jews. Levy’s son David Levy Yulee became a prominent Florida politician in the 1840s and championed the state’s secession in 1861.

Moses Levy’s agrarian dream never materialized, and the Jewish population of Florida grew slowly in the subsequent decades. There were perhaps 40 Jews living in Florida at the end of the 1820s, and that figure remained below 100 when Florida became a state in 1845. Small populations lived in Pensacola, St. Augustine, Daytona, Tallahassee, and other towns, but none had the stability or means to establish Jewish institutions. The concentration of Jews in the towns of North Florida reflected the states general development at that time, as mosquitos, tropical diseases, Seminole resistance, and a lack of infrastructure had hampered Euro-American settlement in other parts of the state.

Jewish migration picked up somewhat in the 1850s, as the state drew a small fraction of the Central European Jews seeking economic and civic liberties in the United States. Samuel Fleischman and several relatives began to arrive in Marianna and Quincy area in 1849. Pensacola and Jacksonville also attracted Jews from German speaking territories, most of whom worked as peddlers and then shopkeepers. In 1857, Jacksonville Jews established a cemetery, the state’s first permanent Jewish institution.

Prior to the Civil War, affluent Jews in Florida enslaved African Americans at similar rates as other established merchants. As in other parts of the South, Jews tended not to own large plantations that were home to large numbers of enslaved workers. During the secession crisis and the following war, Jewish Floridians demonstrated mixed feelings about the Confederacy and the cause of slavery. Some Jews fought enthusiastically for Confederate Army, while others fled to the North, either permanently or for the duration of the war. Morris Dzialynski of Jacksonville fought for the Confederacy and was wounded in action. After receiving a medical discharge, he reportedly served as a blockade runner, but he also spent time in New York City, where he was married in 1865.

Moses Levy’s agrarian dream never materialized, and the Jewish population of Florida grew slowly in the subsequent decades. There were perhaps 40 Jews living in Florida at the end of the 1820s, and that figure remained below 100 when Florida became a state in 1845. Small populations lived in Pensacola, St. Augustine, Daytona, Tallahassee, and other towns, but none had the stability or means to establish Jewish institutions. The concentration of Jews in the towns of North Florida reflected the states general development at that time, as mosquitos, tropical diseases, Seminole resistance, and a lack of infrastructure had hampered Euro-American settlement in other parts of the state.

Jewish migration picked up somewhat in the 1850s, as the state drew a small fraction of the Central European Jews seeking economic and civic liberties in the United States. Samuel Fleischman and several relatives began to arrive in Marianna and Quincy area in 1849. Pensacola and Jacksonville also attracted Jews from German speaking territories, most of whom worked as peddlers and then shopkeepers. In 1857, Jacksonville Jews established a cemetery, the state’s first permanent Jewish institution.

Prior to the Civil War, affluent Jews in Florida enslaved African Americans at similar rates as other established merchants. As in other parts of the South, Jews tended not to own large plantations that were home to large numbers of enslaved workers. During the secession crisis and the following war, Jewish Floridians demonstrated mixed feelings about the Confederacy and the cause of slavery. Some Jews fought enthusiastically for Confederate Army, while others fled to the North, either permanently or for the duration of the war. Morris Dzialynski of Jacksonville fought for the Confederacy and was wounded in action. After receiving a medical discharge, he reportedly served as a blockade runner, but he also spent time in New York City, where he was married in 1865.

Late 19th and Early 20th Centuries

Jewish women of Pensacola, c. 1890. State Archives of Florida.

Jewish women of Pensacola, c. 1890. State Archives of Florida.

Jewish migration to Florida increased during Reconstruction, and local Jews began forming social and religious organizations in the 1870s. The first Jewish congregation in Florida, Temple Beth-El in Pensacola, received its charter in 1876. Jewish communities developed roots in a number of towns and cities by the end of the century, but only six were home to formal congregations: Pensacola, Jacksonville, Key West, Ocala, Tampa, and St. Augustine. Across Florida, Jewish citizens became civic and business leaders, with Jewish mayors serving in Tampa, Deland, Marianna, and Jacksonville before the end of the century. While many Jews found their way to Florida as traders and merchants, others came for the state’s agricultural opportunities, especially as the citrus industry developed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Jewish life in Florida became increasingly organized in the early decades of the 20th century, with new congregations forming in Miami (1913), Orlando (1918), and Sarasota (1925). In Pensacola, Jacksonville, Tampa, and other cities, disagreements over religious practice led to the formation of new synagogues. American born Jews and established families often preferred Reform practices, whereas new immigrants from Eastern Europe tended to push for more traditional observances. A few of the Eastern European newcomers promoted Jewish secularism, and they established small groups of their own in Jacksonville, Pensacola, and—later—Miami.

Jewish life in Florida became increasingly organized in the early decades of the 20th century, with new congregations forming in Miami (1913), Orlando (1918), and Sarasota (1925). In Pensacola, Jacksonville, Tampa, and other cities, disagreements over religious practice led to the formation of new synagogues. American born Jews and established families often preferred Reform practices, whereas new immigrants from Eastern Europe tended to push for more traditional observances. A few of the Eastern European newcomers promoted Jewish secularism, and they established small groups of their own in Jacksonville, Pensacola, and—later—Miami.

Booms, Busts, and Post-WWII Growth

Since the 19th century, Florida’s Jewish communities have grown in uneven surges, determined in large part by the state’s overall boom-and-bust economic cycle. Early on, disease outbreaks and crop failures impeded settlement and development. Real estate booms and land speculation fueled growth, especially the 1890s and 1920s, but were followed by sharp downturns. The collapse of the Florida real estate market in 1925 was followed by hurricanes that hit South Florida in 1926 and 1928, the beginning of the Great Depression nationally, and a Mediterranean fruit fly infestation.

The state’s economy did not recover until the United States entered World War II in 1941, and Jewish populations stagnated in many Florida cities. Jews from the urban North continued to move to the Miami area, however, which surpassed Jacksonville as Florida’s largest Jewish center by the early 1930s. As the country began to mobilize for war, military construction projects brought in millions of Federal dollars, service members flooded into bases and training facilities across the state, and Florida farms and factories provided food and industrial products for the war effort. The pesticide DDT made Florida more habitable for humans while citrus concentrates made farming more profitable, and the U.S. Army popularized both technologies. World War II also exposed many Jewish soldiers to Florida’s warm winters and tropical beaches, and a significant number of young veterans settled there after the war. Affordable commercial air travel and the popularization of residential air conditioning also contributed to Florida’s population growth in the mid-20th century.

South Florida received the majority of Florida’s Jewish post-war migrants, but real estate booms in Southwest Florida led to the establishment of Jewish communities in Fort Myers (1954) and Naples (1962). Jewish populations also grew rapidly in Tampa, St. Petersburg, and Sarasota. In Brevard County (the “Space Coast”) the development of Cape Canaveral and the Kennedy Space Center attracted Jewish workers in the aerospace industry, construction, real estate, and other fields, who organized their own Jewish community beginning in the early 1950s. As in other parts of the country, some of Florida’s smallest Jewish communities, especially in North Florida and inland areas experienced significant declines during this period and shortly after.

The mid-century boom also brought the first large waves of Jewish retirees to Florida, with older Jews moving in large numbers first to Miami Beach and then to other parts of South Florida. Jewish retirees also make up significant portions of the Jewish community in Southwest Florida and in some congregations in the Florida Panhandle. While Palm Beach and (to a lesser degree) Broward Counties remain the most popular destinations for older Jewish migrants, new retirement developments continue to affect the distribution of Jews in Florida. By the early 21st century, for example, a Jewish congregation had begun to form in The Villages, a massive, age-restricted, planned community north of Orlando, and the Jewish population there continues to grow as of 2019.

The state’s economy did not recover until the United States entered World War II in 1941, and Jewish populations stagnated in many Florida cities. Jews from the urban North continued to move to the Miami area, however, which surpassed Jacksonville as Florida’s largest Jewish center by the early 1930s. As the country began to mobilize for war, military construction projects brought in millions of Federal dollars, service members flooded into bases and training facilities across the state, and Florida farms and factories provided food and industrial products for the war effort. The pesticide DDT made Florida more habitable for humans while citrus concentrates made farming more profitable, and the U.S. Army popularized both technologies. World War II also exposed many Jewish soldiers to Florida’s warm winters and tropical beaches, and a significant number of young veterans settled there after the war. Affordable commercial air travel and the popularization of residential air conditioning also contributed to Florida’s population growth in the mid-20th century.

South Florida received the majority of Florida’s Jewish post-war migrants, but real estate booms in Southwest Florida led to the establishment of Jewish communities in Fort Myers (1954) and Naples (1962). Jewish populations also grew rapidly in Tampa, St. Petersburg, and Sarasota. In Brevard County (the “Space Coast”) the development of Cape Canaveral and the Kennedy Space Center attracted Jewish workers in the aerospace industry, construction, real estate, and other fields, who organized their own Jewish community beginning in the early 1950s. As in other parts of the country, some of Florida’s smallest Jewish communities, especially in North Florida and inland areas experienced significant declines during this period and shortly after.

The mid-century boom also brought the first large waves of Jewish retirees to Florida, with older Jews moving in large numbers first to Miami Beach and then to other parts of South Florida. Jewish retirees also make up significant portions of the Jewish community in Southwest Florida and in some congregations in the Florida Panhandle. While Palm Beach and (to a lesser degree) Broward Counties remain the most popular destinations for older Jewish migrants, new retirement developments continue to affect the distribution of Jews in Florida. By the early 21st century, for example, a Jewish congregation had begun to form in The Villages, a massive, age-restricted, planned community north of Orlando, and the Jewish population there continues to grow as of 2019.

The 21st Century

At the beginning of the 21st Century, the enormous Jewish population of South Florida draws more attention than the Jewish communities of the smaller metropolitan areas of Tampa, Orlando, and Jacksonville, and it completely dwarfs the Jewish presence in the state’s small cities. Still, educational, medical, and government hubs such as Tallahassee and Gainesville maintain stable and even growing Jewish populations, and the University of Florida, located in Gainesville, claims the most Jewish students of any school in the country (although the actual number is debated).

Despite South Florida’s mid-20th century divergence from the rest of the state and from most of the Jewish South, the story of Jewish Florida remains rooted in the state’s longer history, from European colonization and the growth of plantation agriculture to its emergence as the United States’ gateway to the Carribean.

Despite South Florida’s mid-20th century divergence from the rest of the state and from most of the Jewish South, the story of Jewish Florida remains rooted in the state’s longer history, from European colonization and the growth of plantation agriculture to its emergence as the United States’ gateway to the Carribean.

Additional Resources

Florida Jewish History Bibliography by the Southern Jewish Historical Society

Florida Jewish Heritage Trail, Florida Department of State, Division of Historical Resources (2000). Online at archive.org.

The Florida Jewish Newspaper Project, University of Florida Digital Collections.

Collections of the Jewish Museum of Florida, originated by Marcia Jo Zerivitz, Florida International University.

MOSAIC Collection, images of Jewish life in Florida, available through the State Library & Archives of Florida.

Henry A. Green and Marcia Kerstein Zerivitz, Mosaic: Jewish Life in Florida (Coral Gables, Florida: MOSAIC, Inc., 1991).

Florida Jewish History Bibliography by the Southern Jewish Historical Society

Florida Jewish Heritage Trail, Florida Department of State, Division of Historical Resources (2000). Online at archive.org.

The Florida Jewish Newspaper Project, University of Florida Digital Collections.

Collections of the Jewish Museum of Florida, originated by Marcia Jo Zerivitz, Florida International University.

MOSAIC Collection, images of Jewish life in Florida, available through the State Library & Archives of Florida.

Henry A. Green and Marcia Kerstein Zerivitz, Mosaic: Jewish Life in Florida (Coral Gables, Florida: MOSAIC, Inc., 1991).