Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Micanopy, FL

Overview

Micanopy, founded in 1821, is the oldest inland town in Florida. In 1822, Moses Elias Levy, a Moroccan-born Sephardic Jew, became a surprising part of the small settlement’s story, migrating from Cuba to St. Augustine and setting his sights on Alachua County for an intended agricultural utopia. In addition to being a model of communal living, Levy’s wanted his project to serve as a refuge for Jews fleeing religious persecution in Europe. Levy’s communitarian experiment, Pilgrimage Plantation, never truly succeeded in and of itself, yet exercised influence on Micanopy’s development, both in its role fostering a regional sugarcane industry, and in Micanopy’s involvement with the Florida Association, a New York-based real estate company that contributed early funding to the settlement. The community never saw the formation of formal organized Jewish life, neither during the Plantation’s thirteen-year existence or after Seminole tribes burned it to the ground in 1835. Yet Levy’s religiously motivated Pilgrimage Plantation has an importance in Southern Jewish history—as an aberration not necessarily in the goals and visions of its founders, but in its identity as a Jewish communal project in a Southern state.

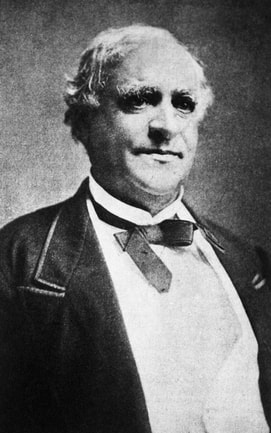

Moses Elias Levy

Moses Elias Levy was born in 1782 in Mogador, Morocco under the original surname “Yuli.” The son of a Sephardic merchant and a courtier, Levy lived out his early childhood under the reign of Sultan Sidi Muhammad III. The rise of Sultan Mulay Yazid in 1790 worsened treatment for Jews in Morocco and the Yuli family migrated to British Gibraltar, on the tip of the Iberian Peninsula. Towards the end of the 19th century, the death of Levy’s father influenced his desire to leave British Gibraltar and he set his sights on the Caribbean, where he had seen migrants he knew experience success as merchants. In 1800 Levy set out for the Danish West Indies, discarding the surname Yuli in the process.

Levy worked in a lumber export company and even though he was not in agrarian field, he saw large-scale plantation agriculture all around him. On the hilly island of St. Thomas, sugarcane was a prominent part of the landscape, grown on man made terraces and harvested by slaves. Over the next two decades Levy accrued a small fortune in lumber and began his own firm, for which he travelled often to Puerto Rico and Cuba, He married Hannah Abendanone in 1803, in what was likely an arranged marriage, and they had four children over twelve years.

By the end of his first decade in the Caribbean, Levy grew morally unsatisfied, particularly burdened by his wealth. In 1815 an outlet for this dissatisfaction began to take shape as Levy noted a resurgence of anti-Semitism in Europe. Levy hoped to use his wealth to build a refuge for Jews fleeing religious persecution—an egalitarian and communitarian agricultural utopia. That same year Levy set out for Europe, where he met with Frederick Warburg, a member of a prominent German banking family. Warburg was the first to sign on to Levy’s scheme, agreeing to contribute money and recruit settlers.

Levy worked in a lumber export company and even though he was not in agrarian field, he saw large-scale plantation agriculture all around him. On the hilly island of St. Thomas, sugarcane was a prominent part of the landscape, grown on man made terraces and harvested by slaves. Over the next two decades Levy accrued a small fortune in lumber and began his own firm, for which he travelled often to Puerto Rico and Cuba, He married Hannah Abendanone in 1803, in what was likely an arranged marriage, and they had four children over twelve years.

By the end of his first decade in the Caribbean, Levy grew morally unsatisfied, particularly burdened by his wealth. In 1815 an outlet for this dissatisfaction began to take shape as Levy noted a resurgence of anti-Semitism in Europe. Levy hoped to use his wealth to build a refuge for Jews fleeing religious persecution—an egalitarian and communitarian agricultural utopia. That same year Levy set out for Europe, where he met with Frederick Warburg, a member of a prominent German banking family. Warburg was the first to sign on to Levy’s scheme, agreeing to contribute money and recruit settlers.

Levy’s Florida Arrival

After a failed attempt to secure land in the Midwest, Levy opted to establish his settlement in Florida. In 1819 he used his station in Cuba to buy 52,900 acres of land as part of the Arredondo land grant of 1820. Under this agreement, Levy exchanged land that he already held for a ⅛ stake in the land grant, becoming one of four major investors tasked with fulfilling the requirements of the original Spanish grant, namely bringing new settlers to the region. Levy now owned a large swath of land located in present-day Alachua County, including 20,000 acres north of the United State’s first inland Florida settlement—Micanopy.

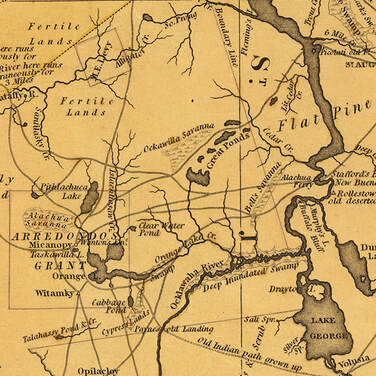

Map detail showing the Arredondo land grant (lower left) and additional land owned by Levy, 1823. State Archives of Florida.

Map detail showing the Arredondo land grant (lower left) and additional land owned by Levy, 1823. State Archives of Florida.

Levy arrived in St. Augustine in 1822, one year after Florida became a United States Territory. He and his wife divorced, and he left behind his daughters, while bringing his two sons to the United States. He brought a large supply of Cuban sugarcane with him to Florida. Even though farmers had grown sugarcane near New Smyrna in Volusia County in the 1760s, early plantations had failed and most mass production would not pick up again until the 1880s.Some witnesses claimed it was the first sugarcane in Florida. Regardless, Levy’s use of the crop would bear influence on the region in the early to mid-19th century.

Not all of Levy’s supporters felt as excited about a Florida settlement as they had about a Midwestern one. Those outside the territory were apt to view Florida as a frontier filled with runaway slaves, hostile Native American tribes and tropical disease. Moses, Myers and Son had withdrew support for the project even while Samuel Meyers took on guardianship of Levy’s young son, David.

After arriving in Florida, Levy bought two smaller pieces of land in addition to his Alachua holdings—1,200 acres on the Matanzas River and 4,000 acres near present-day Ocala and Daytona Beach. The latter he called Hope Hill Plantation. These two additional plantations proved short ventures. Levy sold the Matanzas property and abandoned Hope Hill, the culmination of a conflict with a nearby trader, Horatio Dexter, who saw Levy as unwanted competition with his established business.

Not all of Levy’s supporters felt as excited about a Florida settlement as they had about a Midwestern one. Those outside the territory were apt to view Florida as a frontier filled with runaway slaves, hostile Native American tribes and tropical disease. Moses, Myers and Son had withdrew support for the project even while Samuel Meyers took on guardianship of Levy’s young son, David.

After arriving in Florida, Levy bought two smaller pieces of land in addition to his Alachua holdings—1,200 acres on the Matanzas River and 4,000 acres near present-day Ocala and Daytona Beach. The latter he called Hope Hill Plantation. These two additional plantations proved short ventures. Levy sold the Matanzas property and abandoned Hope Hill, the culmination of a conflict with a nearby trader, Horatio Dexter, who saw Levy as unwanted competition with his established business.

Pilgrimage Plantation (1823 - 1835)

Levy established Pilgrimage Plantation at 1,000 acres, clearing 120 acres immediately for sugarcane, corn, and subsistence crops. The first settlers arrived between 1822 and 1823, and no data exists on the first numbers. What is known is that initial Pilgrimage Plantation inhabitants were recruited by Frederick Warburg and the Florida Association, who sponsored newspaper advertisements for the project and signed on for at least one year. One of the other proprietors from the Arredondo Land Grant founded the Florida Association in New York been to carry out the Spanish land grant stipulations, including the recruitment of settlers to the Territory. The Florida Association’s work benefited the larger Micanopy community as well. They built up roads and infrastructure and worked to bring settlers to the area. Levy was invested in the community as well, which was the inland Plantation’s source for goods and supplies.

Levy considered himself deeply religious and focused his faith on the Hebrew bible, rather than Rabbinic authority. Therefore he never had a plan to establish a synagogue at Pilgrimage Plantation or to enforce Orthodox custom. He believed that as God’s chosen people, Jews should live their lives as close to those in ancient Israel as possible, but to him this meant working the land and concentrating on religious education rather than follow Orthodox law, such as kashrut. He felt that contemporary Judaism had done too much to seperate men and women in religious observance, and while it is speculated he abstained from pork, he and his fellow settlers did not observe all aspects of dietary law. Levy envisioned the establishment of a chenuch—a religious school where boys and girls would both be educated in subjects such as botany and mathematics, and where boys would take on agricultural training, while girls received classes in cooking and sewing.

Advocating for gender equality in an “egalitarian” society, was not the only component of Levy’s ideology that contradicted itself. Levy was a well-known advocate for the abolition of slavery, yet he also held slaves. In fact, it is thought that enslaved people consistently made up the majority of the population at the Pilgrimage Plantation, with estimates at different time periods ranging from 15 to 31 at a time where there were only eight to nine white settlers present. Most enslaved people at Pilgrimage were Africans who had been enslaved by Seminole tribes, and who were exchanged in trades between the Plantation and the local tribes. These workers were paid in “Indian trade goods” rather than nothing at all.

Levy was an advocate of “gradual emancipation,” a system whereby current enslaved peoples would never be freed, but whereby their children would be freed at twenty-one after receiving agricultural training and a Christian education, for “proper conduct and morality.” In the Hebrew Bible Levy found validation for his views, noting that the text condoned slave holding while stating that one must treat enslaved people humanely. Levy’s views were simultaneously progressive for the time and place, while also remaining paternalistic and based in a worldview that saw black and white as inherently different.

Levy intended the bulk of Pilgrimage Plantation to be dedicated to sugarcane production, which he knew from his time on St. Thomas was a labor-intensive process, carried out completely by the labor of enslaved people in the plantation model. Alongside with sugarcane and other crops, settlers and slaves raised livestock on the Plantation, including hogs, which were likely intended only for enslaved workers.

Levy considered himself deeply religious and focused his faith on the Hebrew bible, rather than Rabbinic authority. Therefore he never had a plan to establish a synagogue at Pilgrimage Plantation or to enforce Orthodox custom. He believed that as God’s chosen people, Jews should live their lives as close to those in ancient Israel as possible, but to him this meant working the land and concentrating on religious education rather than follow Orthodox law, such as kashrut. He felt that contemporary Judaism had done too much to seperate men and women in religious observance, and while it is speculated he abstained from pork, he and his fellow settlers did not observe all aspects of dietary law. Levy envisioned the establishment of a chenuch—a religious school where boys and girls would both be educated in subjects such as botany and mathematics, and where boys would take on agricultural training, while girls received classes in cooking and sewing.

Advocating for gender equality in an “egalitarian” society, was not the only component of Levy’s ideology that contradicted itself. Levy was a well-known advocate for the abolition of slavery, yet he also held slaves. In fact, it is thought that enslaved people consistently made up the majority of the population at the Pilgrimage Plantation, with estimates at different time periods ranging from 15 to 31 at a time where there were only eight to nine white settlers present. Most enslaved people at Pilgrimage were Africans who had been enslaved by Seminole tribes, and who were exchanged in trades between the Plantation and the local tribes. These workers were paid in “Indian trade goods” rather than nothing at all.

Levy was an advocate of “gradual emancipation,” a system whereby current enslaved peoples would never be freed, but whereby their children would be freed at twenty-one after receiving agricultural training and a Christian education, for “proper conduct and morality.” In the Hebrew Bible Levy found validation for his views, noting that the text condoned slave holding while stating that one must treat enslaved people humanely. Levy’s views were simultaneously progressive for the time and place, while also remaining paternalistic and based in a worldview that saw black and white as inherently different.

Levy intended the bulk of Pilgrimage Plantation to be dedicated to sugarcane production, which he knew from his time on St. Thomas was a labor-intensive process, carried out completely by the labor of enslaved people in the plantation model. Alongside with sugarcane and other crops, settlers and slaves raised livestock on the Plantation, including hogs, which were likely intended only for enslaved workers.

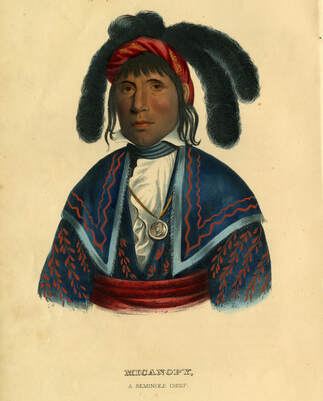

Portrait of Chief Micanopy, 1836. State Archives of Florida.

Portrait of Chief Micanopy, 1836. State Archives of Florida.

The settlers at Pilgrimage Plantation maintained relatively positive relations with Chief Micanopy and the Seminole Indians in the early years. Town members named the community in an early gesture towards Chief Micanopy, and a fruitful trading relationship developed between Pilgrimage Plantation and Pilaklakaha. Also known as “Abraham’s Town,” Pilaklakaha was once the largest Black Seminole village in Florida, run by a former enslaved worker who acted as advisor to Chief Micanopy. Despite early trade however, several early run-ins with tribes scared off some settlers.

While relationships with tribes and Indian traders were sometimes fraught, the Territory held significant advantages for a project such as Levy’s. At the time, Florida was sparsely populated, made up vast tracts of land that had not yet been settled by Euro-American migrants. Florida did not have the rigid “plantation caste system” present elsewhere in the South and inhabitants expressed excitement at the end of the long era of Spanish-Catholic rule. A racial hierarchy existed in Florida, but Levy’s views on “gradual emancipation” would have drawn more suspicion in other Southern states. Also, his plans for an explicitly Jewish utopia may not have been as well received in a region under stronger Christian influence. Considering Levy’s unconventional ideas, prominent figures in the state and region received him well. Acting Governor of Florida William G.D Worthington called him, “one of the most useful settlers in this Province.” Alexander Hamilton Jr., son of Alexander Hamilton, referred to him as a “gentleman of much respectability,” and James G. Forbes, mayor of St. Augustine, was in such support that he acted as Levy’s agent when he travelled.

Yet major obstacles abounded in getting the Plantation off the ground. The urban background of many Jewish migrants made them hard to recruit and retain. As Levy wrote,

“It is not easy to transform old clothes men [street peddlers] or stock brokers into practical farmers.” Pressure mounted in 1823, when the Florida Association reminded Levy he needed to bring 200 settlers over the next three years. By 1824, Frederick Warburg had only managed to recruit a number in the ballpark of “five heads of family,” or 25 settlers.

Despite his intent on a communitarian lifestyle, Levy did not structure Pilgrimage Plantation in a way to reap the most communal benefit. Instead of sharing dwellings, or financial burdens, Levy designed Pilgrimage more as a small village, where no stringent labor requirements existed for settlers. Families had their own, comfortable dwellings and five acres of land each. Enslaved workers did the bulk of the labor, but there were not enough to harvest all the sugarcane when it produced at a high capacity. Levy had intended to fall back on land sales for expenses before the Plantation turned a profit, but when questions arose concerning the legality of his land titles, he had no backup funds.

In 1823, Levy hired Reuben Charles to manage Pilgrimage Plantation while he focused on fundraising. Levy’s personal life began to become a source of discontent as well. One of Levy’s son, Elias, left Harvard University to live on the Plantation—a disappointment to his father, who had enrolled him there hoping a degree would benefit the Plantation down the road. Elias’ nineteen-year old brother David joined them shortly afterwards. It was the first time the two sons and their father had lived together in at least a decade and within two years both sons had completely rejected Levy’s ideology and left the Plantation.

Between 1827 and 1828 Levy traveled in Europe, giving public lectures and trying to solicit funds for Pilgrimage Plantation. During this time he anonymously published his pamphlet, A Plan for the Abolition of Slavery. He returned with as much debt as he had departed with.

While relationships with tribes and Indian traders were sometimes fraught, the Territory held significant advantages for a project such as Levy’s. At the time, Florida was sparsely populated, made up vast tracts of land that had not yet been settled by Euro-American migrants. Florida did not have the rigid “plantation caste system” present elsewhere in the South and inhabitants expressed excitement at the end of the long era of Spanish-Catholic rule. A racial hierarchy existed in Florida, but Levy’s views on “gradual emancipation” would have drawn more suspicion in other Southern states. Also, his plans for an explicitly Jewish utopia may not have been as well received in a region under stronger Christian influence. Considering Levy’s unconventional ideas, prominent figures in the state and region received him well. Acting Governor of Florida William G.D Worthington called him, “one of the most useful settlers in this Province.” Alexander Hamilton Jr., son of Alexander Hamilton, referred to him as a “gentleman of much respectability,” and James G. Forbes, mayor of St. Augustine, was in such support that he acted as Levy’s agent when he travelled.

Yet major obstacles abounded in getting the Plantation off the ground. The urban background of many Jewish migrants made them hard to recruit and retain. As Levy wrote,

“It is not easy to transform old clothes men [street peddlers] or stock brokers into practical farmers.” Pressure mounted in 1823, when the Florida Association reminded Levy he needed to bring 200 settlers over the next three years. By 1824, Frederick Warburg had only managed to recruit a number in the ballpark of “five heads of family,” or 25 settlers.

Despite his intent on a communitarian lifestyle, Levy did not structure Pilgrimage Plantation in a way to reap the most communal benefit. Instead of sharing dwellings, or financial burdens, Levy designed Pilgrimage more as a small village, where no stringent labor requirements existed for settlers. Families had their own, comfortable dwellings and five acres of land each. Enslaved workers did the bulk of the labor, but there were not enough to harvest all the sugarcane when it produced at a high capacity. Levy had intended to fall back on land sales for expenses before the Plantation turned a profit, but when questions arose concerning the legality of his land titles, he had no backup funds.

In 1823, Levy hired Reuben Charles to manage Pilgrimage Plantation while he focused on fundraising. Levy’s personal life began to become a source of discontent as well. One of Levy’s son, Elias, left Harvard University to live on the Plantation—a disappointment to his father, who had enrolled him there hoping a degree would benefit the Plantation down the road. Elias’ nineteen-year old brother David joined them shortly afterwards. It was the first time the two sons and their father had lived together in at least a decade and within two years both sons had completely rejected Levy’s ideology and left the Plantation.

Between 1827 and 1828 Levy traveled in Europe, giving public lectures and trying to solicit funds for Pilgrimage Plantation. During this time he anonymously published his pamphlet, A Plan for the Abolition of Slavery. He returned with as much debt as he had departed with.

The End of Levy’s Utopia

In the 1830s, the Florida Territory entered a new set of conflicts with Native American tribes after then-President Andrew Jackson proposed the forced removal of Seminole and Miccosukee tribes to the Arkansas Territory. The Second Seminole War began in 1835, right as Levy claimed Pilgrimage Plantation had finally turned a profit. This same year, Seminole Indians burned Pilgrimage Plantation to the ground, leaving little trace of the thirteen years Levy had spent attempting to build his refuge outside of Micanopy. The U.S Army turned Micanopy into a Fort, but abandoned it in 1836, burning it down before leaving. A December 23, 1835 article in the Tallahassee Floridian suggests there were settlers and enslaved people still residing at Pilgrimage Plantation when it burned, but none were killed.

|

Levy returned to St. Augustine to live with his debt and damaged morale. A land grant document from 1832 put Levy’s total holdings at 65,800 acres, while C.S. Monaco, leading Levy expert, claims he at one point held over 100,000 acres of land. Levy was not able to sell his land until years later, when a court order finally improved his financial situation.

In the meantime, Levy’s son, David, paved his own way in Florida, avidly pursuing a political career. Both David and his brother Elias had rejected their father’s communitarian ideals, anti-slavery sentiments, and Judaism after their time on the Plantation. As Florida’s first Senator, and first Jewish member of Congress, David advocated for slavery and secession as the nation approached Civil War. After he learned of his father’s original surname, David Levy legally changed his name to David Levy Yulee. |

Conclusion

After the end of the Second Seminole War in 1845, Micanopy rebuilt and became a significant site of historical preservation in Florida. Cotton, cattle, and citrus replaced sugarcane as crops, eventually displaced by the lumber and turpentine industries as citrus moved south. When Moses Elias Levy died in 1854, he passed away quietly, having shied from publicity his whole life and severed most family ties. Micanopy never gained a large Jewish population or typical markers of Jewish life, like a cemetery or synagogue, during the existence of Pilgrimage Plantation and it never did afterwards. Nothing is known of the settlers who came and went in Florida’s oldest inland United States settlement, with the exception of Frederick Warburg, who died in Atlona, Germany in 1844.

By the time Florida became a state in 1845, Levy had risen and fallen as one of Florida’s largest landowners. Even after gaining back his economic standing, he never attempted again to bring his vision to life, considering Pilgrimage Plantation a complete failure. He never considered the unusual importance his project held in southern Jewish history, as one of the few Jewish agricultural communitarian experiments in the American South—even if the population was small and it failed after thirteen years. Levy’s influence, through the Florida Association, had an impact on the prosperity of Micanopy as well, and he still features in public accounting of Micanopy history today.

By the time Florida became a state in 1845, Levy had risen and fallen as one of Florida’s largest landowners. Even after gaining back his economic standing, he never attempted again to bring his vision to life, considering Pilgrimage Plantation a complete failure. He never considered the unusual importance his project held in southern Jewish history, as one of the few Jewish agricultural communitarian experiments in the American South—even if the population was small and it failed after thirteen years. Levy’s influence, through the Florida Association, had an impact on the prosperity of Micanopy as well, and he still features in public accounting of Micanopy history today.

Selected Bibliography:

Moncao, Chris. Moses Levy of Florida: Jewish Utopian and Antebellum Reformer. Louisiana State University Press. 2005.

Moncao, Chris. “A Sugar Utopia on the Florida Frontier: Moses Elias Levy’s Pilgrimage Plantation.” Southern Jewish History. Vol 5. 2002.

Zimmerman, Brian. “The Small Florida Town That Could Have Been a Jewish Utopia.” Forward. (2014)

Moncao, Chris. Moses Levy of Florida: Jewish Utopian and Antebellum Reformer. Louisiana State University Press. 2005.

Moncao, Chris. “A Sugar Utopia on the Florida Frontier: Moses Elias Levy’s Pilgrimage Plantation.” Southern Jewish History. Vol 5. 2002.

Zimmerman, Brian. “The Small Florida Town That Could Have Been a Jewish Utopia.” Forward. (2014)