Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Tampa, FL

Overview

The land where present-day Tampa sits was first occupied by a succession of American Indian chiefdoms (primarily the Tocobaga tribe), and its European roots revolve around the erection of Fort Brooke, a barrack intended to “keep watch” on the Indian population. Yet until the late 19th century, Tampa remained fairly remote and had minimal importance to the rest of the nation. The advent of the cigar industry in the west Florida city in the late 19th century brought in new wealth and development, and with that came Jewish merchants. Florida’s rapid population rise over the first two decades of the 20th century included many Jews, and throughout the 1900s the Jewish community continued to grow and integrate into Tampa’s general population. Although the Cigar City does not produce nearly as many cigars as it once did, its new industries make it an important metropolitan center, and Jewish life has continued to flourish in the early 21st century.

Early Jews of Tampa

In 1824 the U.S. military erected Fort Brooke in what eventually became the southern end of downtown Tampa, but the settlement remained a small, isolated town for another half century. With its distance from larger markets in the South, poor roads, and no rail line, travel and trade to the city was especially difficult in the mid-19th century. Further, although the Seminole Wars attracted some economic base and businesses, the conflicts also discouraged many would-be settlers from moving to the area. In the mid-1800s, an early Jewish peddler briefly living in Tampa noted that the town was full of “outlaws, gamblers, roughs, robbers, cutthroats, and lewd women [who] all congregate to cheat the poor, ignorant volunteers and soldiers out of their money.”

Jews in Tampa and the surrounding region date back to the early statehood of Florida. When Florida became the 27th state in 1845, one Jewish woman was operating perhaps the first citrus grove in Hillsborough County. Emmaline Ouentz Miley, who arrived in the region in 1844, married a non-Jewish man and had twelve children in nearby Thonotosassa. According to historical accounts, Emmaline had a moral standing against slavery, and she refused to marry her husband until he sold his slaves. Her citrus grove continued to operate for nearly a century under the name “Miley Grove.” In 1860, Hillsborough County only had 2,981 residents, and, like Miley’s family, its population largely relied on agricultural pursuits and industries like cattle grazing, because the soil was too poor for raising traditional cash crops.

Jewish merchants began to trickle into Tampa in the late 1850s. Max and Fishel White first came to Tampa in 1858, opening a gentlemen’s furnishing store on Washington and Marion Streets. Charles Slager, a devoted member of the Republican Party, came to Tampa after the Civil War and was elected postmaster in 1871. During the Reconstruction years, he also served as Sheriff, tax collector, and on the country school board. By the 1870s, however, many of Tampa’s residents fled from fear of the Yellow Fever and economic downturn following the Panic of 1872. Jews focused their trade elsewhere, including cattle ranches in Florida’s interior, where places like Fort Meade were becoming increasingly important trade centers.

New life, both Jewish and non, came to the city the following decade with the arrival of the railroad in 1884. Rail access brought new industry; most prominently, cigar manufacturing proved to be highly profitable and was soon relocated from Key West to Ybor City in Tampa’s downtown district.

Jews in Tampa and the surrounding region date back to the early statehood of Florida. When Florida became the 27th state in 1845, one Jewish woman was operating perhaps the first citrus grove in Hillsborough County. Emmaline Ouentz Miley, who arrived in the region in 1844, married a non-Jewish man and had twelve children in nearby Thonotosassa. According to historical accounts, Emmaline had a moral standing against slavery, and she refused to marry her husband until he sold his slaves. Her citrus grove continued to operate for nearly a century under the name “Miley Grove.” In 1860, Hillsborough County only had 2,981 residents, and, like Miley’s family, its population largely relied on agricultural pursuits and industries like cattle grazing, because the soil was too poor for raising traditional cash crops.

Jewish merchants began to trickle into Tampa in the late 1850s. Max and Fishel White first came to Tampa in 1858, opening a gentlemen’s furnishing store on Washington and Marion Streets. Charles Slager, a devoted member of the Republican Party, came to Tampa after the Civil War and was elected postmaster in 1871. During the Reconstruction years, he also served as Sheriff, tax collector, and on the country school board. By the 1870s, however, many of Tampa’s residents fled from fear of the Yellow Fever and economic downturn following the Panic of 1872. Jews focused their trade elsewhere, including cattle ranches in Florida’s interior, where places like Fort Meade were becoming increasingly important trade centers.

New life, both Jewish and non, came to the city the following decade with the arrival of the railroad in 1884. Rail access brought new industry; most prominently, cigar manufacturing proved to be highly profitable and was soon relocated from Key West to Ybor City in Tampa’s downtown district.

Ybor City

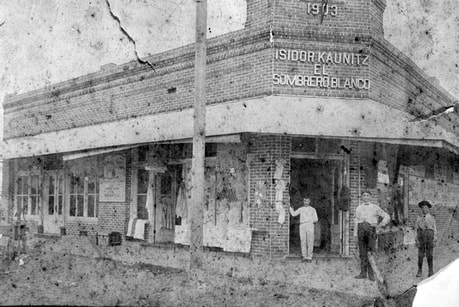

Business of Isidor Kaunitz in Ybor City, c. 1905. Once an independent town, Tampa annexed Ybor city in 1887. State Archives of Florida.

Business of Isidor Kaunitz in Ybor City, c. 1905. Once an independent town, Tampa annexed Ybor city in 1887. State Archives of Florida.

With the cigar industry came a new Jewish immigrant merchant class, many of whom catered their businesses to the cigar workers. Other Jews went to West Tampa, another independent cigar manufacturing city at its founding. Of the earliest post-railroad era arrivals was Herman Glogowski, a German native who in the coming decades served as a city councilman and four terms as mayor, and helped to organize the local Tampa fire department.

In 1886 and 1887, Abe and Isaac Maas moved to Tampa and opened the Maas Brothers department store. Its first location was just a 23-by-90-foot store located on East Twiggs Street, but it grew to become one of Florida’s largest department store chains over the next hundred years. Other early merchants included Isidor Kaunitz, who operated El Sombrero Blanco named after the white hat he wore, as well as the Kaunitz, Barsh, Oppenheimer, Wolf, and Wohl families.

Like other places in Florida, Jews in Tampa campaigned and fundraised for Cuban independence in the 1890s, years before the United States officially got involved in 1898. Jews commonly explained that they related the Spanish governance over the Cuban people to its repressive regime against Jews in Spain the 14th and 15th century Inquisition. Edward, Joseph, and Max Steinburg were among those most active in supporting Cuban independence, all raising large sums of money for the Cuban revolutionaries. According to legend, revolution leader José Martí called the three brothers “the most effective, devoted, and unselfish friends that the Liberty of Cuba ever had in foreign hearts.”

In 1886 and 1887, Abe and Isaac Maas moved to Tampa and opened the Maas Brothers department store. Its first location was just a 23-by-90-foot store located on East Twiggs Street, but it grew to become one of Florida’s largest department store chains over the next hundred years. Other early merchants included Isidor Kaunitz, who operated El Sombrero Blanco named after the white hat he wore, as well as the Kaunitz, Barsh, Oppenheimer, Wolf, and Wohl families.

Like other places in Florida, Jews in Tampa campaigned and fundraised for Cuban independence in the 1890s, years before the United States officially got involved in 1898. Jews commonly explained that they related the Spanish governance over the Cuban people to its repressive regime against Jews in Spain the 14th and 15th century Inquisition. Edward, Joseph, and Max Steinburg were among those most active in supporting Cuban independence, all raising large sums of money for the Cuban revolutionaries. According to legend, revolution leader José Martí called the three brothers “the most effective, devoted, and unselfish friends that the Liberty of Cuba ever had in foreign hearts.”

Organized Jewish Life

A bust of Herman Glogowski, Tampa mayor and founding member of Schaarai Zedeck, stands on the Tampa Riverwalk. Wikimedia Commons, edited.

A bust of Herman Glogowski, Tampa mayor and founding member of Schaarai Zedeck, stands on the Tampa Riverwalk. Wikimedia Commons, edited.

By 1890, at least 20 Jewish families lived in Tampa, and it was clear that more would be arriving soon. Tampa experienced enormous growth between 1880 and 1890, growing over sevenfold in just ten years. With the city continuing to welcome new arrivals every day, former mayor Herman Glogowski organized an effort to establish a formal congregation. In October, 1894, 31 men and women met to found Schaarai Zedek (Gates of Righteousness), and two months later the group received its Orthodox Union charter. The congregation bought a Torah for $75 and elected Glogowski as its first president, while Rabbi D. Jacobson became the first spiritual leader. That same year, the first Jewish religious school opened at Mrs. Baker’s Dancing Academy. In 1896, the congregation purchased a one-acre plot of land in the Woodlawn Cemetery, and the first burial—that of S. Solomon—occurred the same year. A Hebrew Benevolent Society was founded shortly after to maintain the site. The congregation met and prayed in a private home until 1899, when the group had raised enough money to buy their own synagogue. That same year, female congregants organized the Ladies Temple Guild to assist the temple financially. They held a bazaar fundraiser to furnish the new building, help pay off the synagogue’s mortgage, and finance the religious school.

Abe Maas, co-owner of Maas Bros. department store and longtime member of Schaarai Zedeck. State Archives of Florida.

Abe Maas, co-owner of Maas Bros. department store and longtime member of Schaarai Zedeck. State Archives of Florida.

Schaarai Zedek’s charter with the Orthodox movement did not last long, however, as ideological differences between members disrupted the cohesiveness of the congregation. In part, the massive influx of new Jewish arrivals likely caused a shift in practices. Between 1886 and 1900, the Jewish population grew over twofold, from 720 to 1,600. But in 1902, just three years after Glogowski laid the cornerstone on their new building, a group of “reformers” came into conflict with the traditional Orthodox congregants. After a yearlong legal battle and more than 270 pages of testimony, the reformers gained control of the synagogue assets, and in 1903 the congregation switched its charter to become part of the Union of American Hebrew Congregation (now the Union for Reform Judaism). Abe Maas became the president of Schaarai Zedek and remained in the role for 24 years.

After the split in the community, the traditional members of Schaarai Zedek formed into a new Orthodox congregation, calling themselves Rodeph Sholom (Pursuers of Peace). Henry Brash, a former mayor of Marianna, Florida, and a haberdashery store owner, led the new group, which consisted of 26 families. With Brash at the helm, they hired Rabbi Julius Hess to be their first spiritual leader and built a new synagogue and religious school on Palm Avenue in 1903.

After the split in the community, the traditional members of Schaarai Zedek formed into a new Orthodox congregation, calling themselves Rodeph Sholom (Pursuers of Peace). Henry Brash, a former mayor of Marianna, Florida, and a haberdashery store owner, led the new group, which consisted of 26 families. With Brash at the helm, they hired Rabbi Julius Hess to be their first spiritual leader and built a new synagogue and religious school on Palm Avenue in 1903.

Early 20th Century

The new century continued to bring massive population growth, and with it came a new wealth of Jewish businesses and culture to Tampa life. The cigar industry brought in workers from a wide array backgrounds, including Latin Americans, Italians, Cubans, and Germans, and provided deep cultural diversity to Ybor City and West Tampa. Together, these cigar factory workers hand-rolled upwards of eight million cigars per week, with estimates that the industry made up a third of Florida’s annual income at the turn of the century. Many of the Jews lived along 7th Avenue in Ybor City and learned Spanish as they interacted with the Hispanic population.

Max Argintar’s pawn shop, 1908. State Archives of Florida.

Max Argintar’s pawn shop, 1908. State Archives of Florida.

The first half of the new century saw at least 80 Jewish stores and institutions open in Ybor City, including Offim and Morris Falk’s O. Falk & Brother Dry Goods and Millinery Store, which soon became the second largest store in Tampa behind Maas Bros. David and Toba Rippa moved their cigar factory to Ybor City in 1904 from Key West, where the cigar industry was in decline. Six years after he came to Tampa in 1902, Max Argintar opened a pawnshop, which became a men’s store in 1916 and remained open in the same location until 2004. Aiding Jewish businesses in Tampa were newcomers from New York, where the Industrial Removal Office sent young immigrants at the request of Tampa’s Jewish merchants.

Religious institutions also opened in the early 1900s in Ybor City. The Hebrew School, Tampa’s first Jewish day school, formed in 1915 but closed two years later after defaulting on its mortgage payments. The Young Men’s Hebrew Association was organized in 1906 and eventually bought a building on Ross and Nebraska Ave. Interestingly, as Jewish merchants opened shops and Jewish groups bought building space in Ybor City, both Schaarai Zedek and Rodeph Sholom moved out of the neighborhood to the nearby Tampa Heights district. In 1918 the Reform Schaarai Zedek moved to 1901 North Central Ave, but it soon outgrew this space. It spent a year holding services in various halls and churches around the city before dedicating a new synagogue on Delaware and DeLeon Streets in 1924. In 1925 the Orthodox Rodeph Shalom moved to 309 East Palm Ave.

Religious institutions also opened in the early 1900s in Ybor City. The Hebrew School, Tampa’s first Jewish day school, formed in 1915 but closed two years later after defaulting on its mortgage payments. The Young Men’s Hebrew Association was organized in 1906 and eventually bought a building on Ross and Nebraska Ave. Interestingly, as Jewish merchants opened shops and Jewish groups bought building space in Ybor City, both Schaarai Zedek and Rodeph Sholom moved out of the neighborhood to the nearby Tampa Heights district. In 1918 the Reform Schaarai Zedek moved to 1901 North Central Ave, but it soon outgrew this space. It spent a year holding services in various halls and churches around the city before dedicating a new synagogue on Delaware and DeLeon Streets in 1924. In 1925 the Orthodox Rodeph Shalom moved to 309 East Palm Ave.

World War I, Boom, and Bust

When the United States entered World War One in 1917, many eligible members of the Jewish community in Tampa enlisted to serve. Max Arginator was one of nearly two hundred Jewish Floridians who served in the armed forces. By the war’s close, Tampa had exploded in size, largely thanks to the real estate boom occurring across Florida. In 1920 the city had nearly 52,000 residents and its Jewish population was the second largest in the state. Jews strengthened this growing community by organizing societies and clubs. Sarah Brash formed the Tampa section of the National Council of Jewish Women in 1924, and Florida Jewish Weekly--the first of many Jewish newspapers in the city—began to operate the same year. Also opening in the 1920s were the Jewish Floridian and The Southern Advocate (which closed after just 11 issues due to the real-estate bust and the subsequent Great Depression).

The 1920s in Tampa was an era of Prohibition and speakeasies, and it saw Jews involved in civic affairs, lodges, and other institutions within the broader Tampa community. For example, many local Jews joined the annual Gasparilla Carnival, in which city residents dress as pirates for a day to celebrate the legends of naval outlaws that once operated around Florida’s coasts. Tampa’s oldest fraternal organization, the Masons Hillsborough Lodge No. 25, had at least three Jewish members in the mid-1920s. ‘Salty’ Sol Fleischman, a well-known sports broadcaster and columnist, began his career in 1928 and became known as the “Dean of Florida’s Sportscasters.” Jewish boys joined Boy Scout troops, some rising all the way to become Eagle Scouts and joining the South Florida recovery effort after devastating storms destroyed much of the Miami region.

Yet the housing bust in Florida and the subsequent Great Depression in 1929 hurt Tampa and its Jewish community. Bank closures forced businesses like Fleishman’s Globe Clothing and Tailoring Company to shutter their doors. Temple Schaarai Zedek always ran into money issues. Forced to conserve resources, the congregation cut groups like the temple choir in 1930. But a new rabbi, David L. Zielonka, brought new life to the economically depressed congregants by pushing for adult education, an active membership committee, and focusing on future growth.

The 1920s in Tampa was an era of Prohibition and speakeasies, and it saw Jews involved in civic affairs, lodges, and other institutions within the broader Tampa community. For example, many local Jews joined the annual Gasparilla Carnival, in which city residents dress as pirates for a day to celebrate the legends of naval outlaws that once operated around Florida’s coasts. Tampa’s oldest fraternal organization, the Masons Hillsborough Lodge No. 25, had at least three Jewish members in the mid-1920s. ‘Salty’ Sol Fleischman, a well-known sports broadcaster and columnist, began his career in 1928 and became known as the “Dean of Florida’s Sportscasters.” Jewish boys joined Boy Scout troops, some rising all the way to become Eagle Scouts and joining the South Florida recovery effort after devastating storms destroyed much of the Miami region.

Yet the housing bust in Florida and the subsequent Great Depression in 1929 hurt Tampa and its Jewish community. Bank closures forced businesses like Fleishman’s Globe Clothing and Tailoring Company to shutter their doors. Temple Schaarai Zedek always ran into money issues. Forced to conserve resources, the congregation cut groups like the temple choir in 1930. But a new rabbi, David L. Zielonka, brought new life to the economically depressed congregants by pushing for adult education, an active membership committee, and focusing on future growth.

State Representative Harry Sandler (left) with other Florida politicians, 1935. State Archives of Florida.

State Representative Harry Sandler (left) with other Florida politicians, 1935. State Archives of Florida.

Despite economic hardships, Jews remained in Tampa and continued to integrate into the broader Tampa community in the 1920s and 1930s. Many Jews intermarried with non-Jews and socialized with non-Jews. Unlike their coreligionists across the Tampa Bay in St. Petersburg who experienced some of the worst anti-Semitism in the nation, Jews in Tampa were generally accepted into greater Tampa society with few incidents. Organizations like the Tampa Yacht Country Club, the University Club, and the Rotary Club all accepted Jews as members from their founding. Harry Sandler began his extensive political career in Tampa and was later elected as a Florida legislator in 1932, then became Speaker of the House and was appointed to the 13th Judicial Circuit court in 1935. David Falk became the first Jewish person to be chosen King Gasparilla in 1938. Yet despite this acceptance of Jews, other minority groups did experience discrimination; in particular, the large Hispanic population of Tampa faced the worst of the bigotry.

World War II and the Post-War Population Boom

World War II had yet another major impact on the Jewish communities of Tampa and all across Florida. Three Air Force bases—MacDill, Henderson Field, and Drew Field—brought Jewish soldiers to the region during the war, and many of the newcomers stationed there stayed after 1945. The more established Jews in Tampa welcomed these new arrivals graciously, sponsoring Passover Seders with soldiers and inviting them into the Jewish community. Additionally, many members of Jewish families themselves joined the armed forces during the war. Of the 65 families at Schaarai Zedek, for example, 39 had someone who served in the war. Captain Nellye Israelson became one of the first women to enlist in the Women’s Army Corps, and continued to serve for three years after the war ended.

When the war was won and the depression finally over, Schaarai Zedek focused on its growth. The YMHA became the Jewish Community Center, and the recently founded B’nai B’rith Women fundraised to aid Israel and benefit the local community. Also active was the Temple Sisterhood, which donated $500 for the building of a new Sunday School facility, completed in 1949. By the start of the 1950s, the school enrolled 83 children, and would grow almost twofold by the decade’s end. Similarly, the congregation again began to outgrow its space and built a new temple in 1957. It had enough room to seat 750 people and accommodate the 175 children in the religious school.

When the war was won and the depression finally over, Schaarai Zedek focused on its growth. The YMHA became the Jewish Community Center, and the recently founded B’nai B’rith Women fundraised to aid Israel and benefit the local community. Also active was the Temple Sisterhood, which donated $500 for the building of a new Sunday School facility, completed in 1949. By the start of the 1950s, the school enrolled 83 children, and would grow almost twofold by the decade’s end. Similarly, the congregation again began to outgrow its space and built a new temple in 1957. It had enough room to seat 750 people and accommodate the 175 children in the religious school.

A wedding at Rodoph Sholom Synagogue, 1961. State Archives of Florida.

A wedding at Rodoph Sholom Synagogue, 1961. State Archives of Florida.

By 1960, Florida’s population approached nearly five million people, and the Jewish population had grown from 25,000 in 1940 to nearly 175,000. Most of the growth occurred in the Miami area, but Tampa's Jewish community drew newcomers as well. Schaarai Zedek again expanded its building in 1962 to accommodate for both new arrivals to Florida and for the Baby Boomer generation. In Tampa, the cigar industry—which had taken a large hit during the depression—experienced a small resurgence. Stanford and Millard Newman were both early leaders of this uptick in production after buying a cigar factory in 1958. Also at this time, many Jews fleeing from Fidel Castro’s rise to power in Cuba chose Tampa as their new homes. The Waksman family, for example, left their profitable paint brush company in Cuba and opened a new factory in Ybor City called Corona Brushes, which is still based in Tampa as of 2018.

The 1960s, ‘70s, and ‘80s saw many Jews become civic and professional leaders in various sectors of Tampa’s society. Dr. Richard Hodes served in the Florida House of Representatives for 16 years beginning in 1966. During Jimmy Carter’s run for president in 1975, Hodes gave the nominating speech at the Florida Democratic Convention. Dr. Philip Adler gained notice as he championed racial desegregation of Tampa’s medical system in the 1960s. Brothers Martin and Myron Uman both became successful researchers, Martin studying lightning at the University of Florida while Myron joined the National Research Council and later became the executive director of the research panel advising NASA on rocket design. Sandra Warshaw Freedman, once ranked fifth in the nation in tennis, became a city councilor in 1974 and was elected mayor in 1986—the first woman in Tampa’s history to be elected to the position. As mayor, she organized Tampa’s first march against hate crimes and appointed many minorities and women to city government positions. Helen Gordon Davis became first Tampa female elected to a state office, serving in Florida House for seven terms before being elected to the Florida senate in 1988. The city elected a number of other Jewish city councilors, school board members, and local and Hillsborough county officials to office as well. Even some of the earliest Jewish stores still operated, some having grown and expanded while others remained fixed institutions. The Maas family continued to run Maas Brothers and expanded it to St. Petersburg, Lakeland, Sarasotsa, Clearwater, and Ft. Myers in the 1950s and ‘60s before it eventually merged with present-day Macy’s in 1991.

The 1960s, ‘70s, and ‘80s saw many Jews become civic and professional leaders in various sectors of Tampa’s society. Dr. Richard Hodes served in the Florida House of Representatives for 16 years beginning in 1966. During Jimmy Carter’s run for president in 1975, Hodes gave the nominating speech at the Florida Democratic Convention. Dr. Philip Adler gained notice as he championed racial desegregation of Tampa’s medical system in the 1960s. Brothers Martin and Myron Uman both became successful researchers, Martin studying lightning at the University of Florida while Myron joined the National Research Council and later became the executive director of the research panel advising NASA on rocket design. Sandra Warshaw Freedman, once ranked fifth in the nation in tennis, became a city councilor in 1974 and was elected mayor in 1986—the first woman in Tampa’s history to be elected to the position. As mayor, she organized Tampa’s first march against hate crimes and appointed many minorities and women to city government positions. Helen Gordon Davis became first Tampa female elected to a state office, serving in Florida House for seven terms before being elected to the Florida senate in 1988. The city elected a number of other Jewish city councilors, school board members, and local and Hillsborough county officials to office as well. Even some of the earliest Jewish stores still operated, some having grown and expanded while others remained fixed institutions. The Maas family continued to run Maas Brothers and expanded it to St. Petersburg, Lakeland, Sarasotsa, Clearwater, and Ft. Myers in the 1950s and ‘60s before it eventually merged with present-day Macy’s in 1991.

Jewish Tampa in the Late 20th and Early 21st Centuries

Toward the end of the 20th century, new congregations and religious centers began to form, both in Tampa and in the surrounding suburbs in Hillsborough County. In 1970, parents founded a Jewish day school at Rodeph Sholom with 30 students. Fourteen years later, it moved to the Jewish Community Center and has since grown to over 200 students. In 1976, Rabbi Lazer Rivkin founded the Chabad house in Tampa. Some 80 people organized to form a new Reform congregation in north Tampa in 1986. They named themselves Congregation Beth Am, and opened a temple on West Fletcher Avenue. Other congregations that opened at this time include Congregation Kol Ami (Conservative, founded in 1978), Beth Israel of Sun City Center (Reform, founded in 1982), Beth Shalom of Brandon (Reform, founded in 1990), Or Ahavah (Renewal), Congregation Bais Tefilah (Chabad), and Young Israel (Orthodox). The University of South Florida also runs a Hillel, and two mikvaot have been built in the city. In 1996, the Tampa JCC and Federation were combined with the mission “to support and enrich Jewish life and values in Tampa, in Israel, and worldwide, and to be a unifying force for Jewish activity.” Two new newspapers, the Jewish Floridian of Tampa and the Jewish Press of Tampa both began operation in 1979 and 1988, respectively, reaching out to a local population still determined to be part of a larger Jewish community.

The Jewish community in Tampa today is still growing. As of 2013, the Jewish population was approximately 23,000. As in other major cities, Jews are integrated into general society, and many are quite successful in business and other professions. Notable 21st century figures include Malcom Glazer, former owner of the Tampa Bay Buccaneers and the Manchester United soccer team in England. Under his leadership, the Bucs won their first Super Bowl in 2003. One year after its founding in 2016, the Glazer Family JCC boasted more than 4,400 members. Mitchel and Susie Levin Rice make up part of the leadership team for RMC Property Group, a real estate company holding hundreds of retail and office properties. Yet despite the success of Jews in business and the many Jewish intuitions that keep Jewish culture and religion thriving, the group’s deep roots are still important parts of the narrative of modern day Tampa. Quite literally, Jewish names are still visible in the old Jewish districts, as the former shops of early merchants Buchman, Steinberg, Bergman, and Simovtiz are still painted above the bars and restaurants that now line the streets of Ybor City, tangible reminders of the long and storied history of the city’s founding Jewish members.

The Jewish community in Tampa today is still growing. As of 2013, the Jewish population was approximately 23,000. As in other major cities, Jews are integrated into general society, and many are quite successful in business and other professions. Notable 21st century figures include Malcom Glazer, former owner of the Tampa Bay Buccaneers and the Manchester United soccer team in England. Under his leadership, the Bucs won their first Super Bowl in 2003. One year after its founding in 2016, the Glazer Family JCC boasted more than 4,400 members. Mitchel and Susie Levin Rice make up part of the leadership team for RMC Property Group, a real estate company holding hundreds of retail and office properties. Yet despite the success of Jews in business and the many Jewish intuitions that keep Jewish culture and religion thriving, the group’s deep roots are still important parts of the narrative of modern day Tampa. Quite literally, Jewish names are still visible in the old Jewish districts, as the former shops of early merchants Buchman, Steinberg, Bergman, and Simovtiz are still painted above the bars and restaurants that now line the streets of Ybor City, tangible reminders of the long and storied history of the city’s founding Jewish members.