Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Key West, FL

Overview

Although Key West often invokes images of incredible sunsets and the homes of famous American figures like Ernest Hemingway and Tennessee Williams, an active Jewish population has existed on the island for over 130 years and has been important to the city’s economy and culture from the very beginning. Fifty years before the first permanent Jewish settlers arrived in Key West, Florida in the 1880s, the small, southernmost Florida Key was the richest city per capita in the entire United States due to its position as a port for the Gulf Coast and its salvaging, fishing, and salt manufacturing industries. Most of Florida’s Jews still lived in northern areas of the state in the 19th century, leaving Key West to become South Florida’s first Jewish community. In fact, it was the largest in the region until Miami’s population boom in the early parts of the next century. While much of the Jewish community left the island by the 1930s, a small group continued to exist and thrive throughout the post-World War II years. While Key West’s Jewish congregation can no longer boast about its size as one of the largest in Florida, it still holds the title as the southernmost Jewish congregation in the continental United States.

Early Jews of Key West

Decades before an organized Jewish community existed on the island, a Jewish peddler named Max White happened upon Key West on his travels from New York to Tampa in 1857. He remarked on the “clear brightness” of the island and awed at the “busy thriving little Town” operating there. After living briefly in Tampa and New Orleans, White returned to Key West. He encountered one other Jew in his few years on the island—a Cuban man who spent four weeks there while recovering from an injury—but mostly kept his religious practices to himself. He and a business partner opened a successful clothing store, and, once he made enough money, White returned to New York around 1861.

Newspaper ad for White & Cline, “mercers and tailors,” New Era, 6 Sept., 1862. University of Florida Digital Collections.

Newspaper ad for White & Cline, “mercers and tailors,” New Era, 6 Sept., 1862. University of Florida Digital Collections.

Despite opportunities for success on the wealthy “Enchanted beautiful Isles,” a permanent Jewish presence in Key West did not exist until 1884, arriving not by choice like Max White but instead by fate. By this time, Key West had become the largest city in Florida, with nearly 18,000 residents and a thriving economy, due in large part to its massive military bases protecting the Gulf Coast. Aboard a ship likely headed for New Orleans was Joseph Wolfson, a Russian immigrant moving from New York to the South in hopes of finding economic prosperity. His ship ran aground, however, when passing by Key West, destroying the boat and forcing the passengers onto the island. After realizing the economic opportunities (and probably marveling at the weather), Wolfson wrote to his brother and his brother’s wife and encouraged the two to join him in Florida. Soon, other Jews began to trickle into the prosperous island city. Most came from Romania, Poland, and Russia, and all of the early Jewish residents made money by peddling. Abram Wolkowsky, for example, emigrated from Russia and began peddling in Florida in 1885. He moved to Key West shortly thereafter.

The Jewish residents of Key West did not worship together until 1887. (Later, when the first congregation formally organized, they used this date to mark the start of organized Jewry on the island.) Initially, no dedicated space belonged to the congregation; members prayed in the upstairs of Louis Fine’s furniture store on Duval street, while Fine became one of the group’s early presidents. Other early members of the Jewish community were Joe Cupperberg, Abraham Zimmetbaum, Adolf Louis, Mendel Rippa, and David and Toba Hinda Rippa. If not strictly orthodox, the congregation adhered to traditional practices, and individual customs differed family by family.

The Jewish residents of Key West did not worship together until 1887. (Later, when the first congregation formally organized, they used this date to mark the start of organized Jewry on the island.) Initially, no dedicated space belonged to the congregation; members prayed in the upstairs of Louis Fine’s furniture store on Duval street, while Fine became one of the group’s early presidents. Other early members of the Jewish community were Joe Cupperberg, Abraham Zimmetbaum, Adolf Louis, Mendel Rippa, and David and Toba Hinda Rippa. If not strictly orthodox, the congregation adhered to traditional practices, and individual customs differed family by family.

Establishing a Conch Community

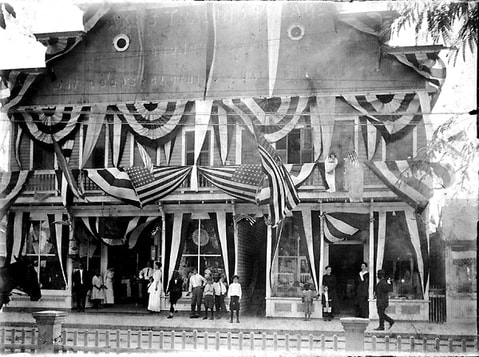

Aronovitz’s Dry Goods Store, c. 1900. State Archives of Florida.

Aronovitz’s Dry Goods Store, c. 1900. State Archives of Florida.

Within just a few years, many of the Jewish peddlers in Key West achieved economic success. Their profits, however, came at the expense of established merchants, who found the Jewish newcomers to be a financial threat to their storefront businesses. The established non-Jewish business owners proposed and passed an 1891 law which required peddlers to pay a $1,000 license fee in order to sell goods on the street with a pushcart. While some Jews viewed this city ordnance as anti-Semitic, it did not in fact impede the Jewish salesmen from obtaining wealth. Instead of ridding the city of Jewish peddlers, the ordinance pushed them to open storefronts, many of which operated on Duval street in the 1890s and early 1900s. These new businesses included Louis Fine’s (dry goods and agent of the Houston Ice and brewing Company), Louis Wolfson’s (dry goods), A. Wolkowsky and Sons (dry goods and clothing), A. Louis (dry goods and clothing), Markovitz & Rippa (dry goods and clothing) and others. Most Jewish businesses supplied either clothing, shoes, furniture, or groceries, although some merchants went into the profitable cigar business. Rebecca Wolkwosky, who operated A. Wolkowsky and Sons with her husband, was known to the town as “Miss Becky” and an “authority on women’s clothes.” For the next few decades, Key Westerners–“Conchs,” as they’re locally known–depended heavily on these Duval street merchants.

As they established themselves as merchants, some members of the Jewish community engaged in political matters outside of the island’s shores as well. Because of Key West’s location just 90 miles north of Havana, the Cuban War for Independence and the subsequent Spanish-American War at the turn of the century became important issues to many on the island, including some of the more outspoken members of the Jewish community. In particular, before the United States officially involved itself in the Cuban war for independence, Louis Fine held rallies and fundraised for the Cuban revolutionaries, something his son later described as a way for his father to “strike back at the Spanish, age-old persecutors” of the Jewish people. In fact, revolutionary leader José Martí gave speeches on Fine’s front porch on Duval and Catherine streets (presently the La Te Da restaurant and hotel). Louis Wolfson supplied Cuban escapees with clothes and food, and worked with a block runner boat. Years later, Fine, Wolfson, and others received awards of recognition for their service and were invited to Cuba for the ceremony. During the Spanish-American War, Jewish families who escaped from Cuba often arrived at the shores of Key West, although most did not permanently settle into the island community. A writer for the Southern Jewish Weekly wrote that “The ashkenazic culture stayed the same: migrating Sephardic Jews from Cuba and points south always just ‘passed through’, looking for more familiar lunzsman [landsmen].” Jews also worked to aid members of the local community. After a disastrous hurricane in 1909 “in which many lost their homes and clothing,” the Miami News reported that David Aronovitz “opened his department store and invited the destitute to come in and clothe themselves adequately.”

As they established themselves as merchants, some members of the Jewish community engaged in political matters outside of the island’s shores as well. Because of Key West’s location just 90 miles north of Havana, the Cuban War for Independence and the subsequent Spanish-American War at the turn of the century became important issues to many on the island, including some of the more outspoken members of the Jewish community. In particular, before the United States officially involved itself in the Cuban war for independence, Louis Fine held rallies and fundraised for the Cuban revolutionaries, something his son later described as a way for his father to “strike back at the Spanish, age-old persecutors” of the Jewish people. In fact, revolutionary leader José Martí gave speeches on Fine’s front porch on Duval and Catherine streets (presently the La Te Da restaurant and hotel). Louis Wolfson supplied Cuban escapees with clothes and food, and worked with a block runner boat. Years later, Fine, Wolfson, and others received awards of recognition for their service and were invited to Cuba for the ceremony. During the Spanish-American War, Jewish families who escaped from Cuba often arrived at the shores of Key West, although most did not permanently settle into the island community. A writer for the Southern Jewish Weekly wrote that “The ashkenazic culture stayed the same: migrating Sephardic Jews from Cuba and points south always just ‘passed through’, looking for more familiar lunzsman [landsmen].” Jews also worked to aid members of the local community. After a disastrous hurricane in 1909 “in which many lost their homes and clothing,” the Miami News reported that David Aronovitz “opened his department store and invited the destitute to come in and clothe themselves adequately.”

Members of the Rosenthal family in Roumania c. 1890, prior to their emigration and arrival in Key West. State Archives of Florida.

Members of the Rosenthal family in Roumania c. 1890, prior to their emigration and arrival in Key West. State Archives of Florida.

Despite integrating into the city’s economy, the Jews of Key West found certain difficulties in their early years on the island. Unsurprisingly, maintaining Jewish life on a remote island at the turn of the century was sometimes a difficult task. If a family chose to keep the traditional laws of kashrut, meat had to be shipped in from Jacksonville. (Miami did not have a kosher butcher yet.) Similarly, pregnant women close to giving birth sometimes travelled to the northern Florida city so a mohel could perform the bris if the child was a boy.

In these early years, the Jews were by no means economically well-off. One Conch reported that “the Jewish people didn’t have fine homes. They lived in either boarding houses or in very modest, indescribably modest, circumstances, because they had no funds and they originally couldn’t speak English.” Like the rest of the town, the Jews also had to deal with bouts of yellow fever, typhoid fever, malaria, and the swarms of “gallon nipper” mosquitoes. Moreover, the best schooling options for Jewish families in Key West were either a Catholic school or a Methodist missionary school, both of which Jewish children attended. Although some Jewish parents were uncomfortable with sending their children to Christian schools and instead sent them to get a Jewish or more secular education elsewhere, for many it became commonplace to attend the local Christian institutions. In fact, as one family history describes, most Jewish Conchs went to Catholic school until the late 20th century. The nuns at the school sent the Jewish kids home for the high holidays and even attended one Jewish student’s bar mitzvah.

In these early years, the Jews were by no means economically well-off. One Conch reported that “the Jewish people didn’t have fine homes. They lived in either boarding houses or in very modest, indescribably modest, circumstances, because they had no funds and they originally couldn’t speak English.” Like the rest of the town, the Jews also had to deal with bouts of yellow fever, typhoid fever, malaria, and the swarms of “gallon nipper” mosquitoes. Moreover, the best schooling options for Jewish families in Key West were either a Catholic school or a Methodist missionary school, both of which Jewish children attended. Although some Jewish parents were uncomfortable with sending their children to Christian schools and instead sent them to get a Jewish or more secular education elsewhere, for many it became commonplace to attend the local Christian institutions. In fact, as one family history describes, most Jewish Conchs went to Catholic school until the late 20th century. The nuns at the school sent the Jewish kids home for the high holidays and even attended one Jewish student’s bar mitzvah.

Organized Jewish Life

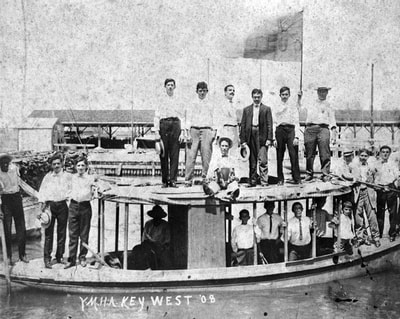

Members of the Young Men’s Hebrew Association on an outing, 1908. State Archives of Florida.

Members of the Young Men’s Hebrew Association on an outing, 1908. State Archives of Florida.

Just after the turn of the 20th century, the rapidly growing Jewish community began to establish Jewish institutions in the island town. In 1907, a group led by Perry Weinberg organized the Young Men’s Hebrew Association (YMHA)—one of three in the state at the time and the first in South Florida—and Weinberg became the group’s first president. As one Jewish resident remembered it, the YMHA was “the organization around which our entire social and literary life revolved.” That same year would be the last that the Jews did not have a dedicated worship space. After years of praying in members’ homes, the congregation hired its first ordained leader, Rabbi Julius Shapo, and in 1908 they bought a doctor’s office at Simonton and Southard streets and converted it into a synagogue. After just three years, however, a “troublesome argument” caused the congregation to split; one faction consisted of a group including David Aronovitz, Herman Pearlman, Theodore Holtsberg, and Mendel Rippa, and the other group was led by David Rosenthal. The first faction called their group Congregation Rodof Shalom, and Rosenthal called his new congregation B’nai Zion. When the two groups rejoined in 1917 under the supervision of Rabbi Gedallah Mendelsohn, the name B’nai Zion stuck and the temple continues under that moniker today. Additionally, members of the Jewish community organized the “first Zionist district” in South Florida in 1915, as members like Louis Lipsky organized drives for the United Palestine Appeal and the Joint Distribution Committee.

Meanwhile, the first two decades of the 20th century saw steady Jewish migration to the city. Jewish businesspeople wanted to become a part of the booming economy of Key West, thanks to the profitable cigar, sponge, ship salvaging, fishing, and military industries. In addition, northern Jewish organizations like the Industrial Removal Office sent new immigrants and helped families transport relatives to the Florida island. Travel to South Florida became increasingly accessible when Henry Flagler completed his Over-Sea Railroad line in 1912, officially connecting Key West to Miami and the rest of the eastern seaboard.

Until the 1920s, the Jewish community continued to thrive in Key West, and it remained the largest center of Jewish life in the southern part of the state. Jews faced nearly no discrimination, and popular white fraternal organizations like Masons, Elks, and Odd Fellows clubs invited Jewish men to join their ranks. During this time Louis Wolfson was elected as a City Commissioner, the first Jew to hold a position in Key West’s city government. Soon, however, as Northerners began to resettle in droves to Miami, Jews would be drawn out of the southernmost Florida key and into mainland South Florida, leaving just a few members of the once thriving community struggling to uphold organized Jewish life.

Meanwhile, the first two decades of the 20th century saw steady Jewish migration to the city. Jewish businesspeople wanted to become a part of the booming economy of Key West, thanks to the profitable cigar, sponge, ship salvaging, fishing, and military industries. In addition, northern Jewish organizations like the Industrial Removal Office sent new immigrants and helped families transport relatives to the Florida island. Travel to South Florida became increasingly accessible when Henry Flagler completed his Over-Sea Railroad line in 1912, officially connecting Key West to Miami and the rest of the eastern seaboard.

Until the 1920s, the Jewish community continued to thrive in Key West, and it remained the largest center of Jewish life in the southern part of the state. Jews faced nearly no discrimination, and popular white fraternal organizations like Masons, Elks, and Odd Fellows clubs invited Jewish men to join their ranks. During this time Louis Wolfson was elected as a City Commissioner, the first Jew to hold a position in Key West’s city government. Soon, however, as Northerners began to resettle in droves to Miami, Jews would be drawn out of the southernmost Florida key and into mainland South Florida, leaving just a few members of the once thriving community struggling to uphold organized Jewish life.

Navigating the Exodus and the Depression

By the mid-1920s, the population of Key West began a major decline. Shortly after, the Great Depression and the decline of the town’s major industries left nearly half of Key West’s adults in need of state or federal relief, and the town’s population had fallen from 30,000 in 1920 to just 12,000 fifteen years later. The Jewish community especially felt this burden; only twelve families remained by the 1930s, hardly enough for a regular minyan of ten adult males. The remaining members voted Joe Pearlman as president of B’nai Zion in 1925, trusting that he would sustain an active Jewish community during this era of decline. Pearlman became instrumental in both the Jewish and non-Jewish sphere over the next half-century, notably serving as chairman of the Key West Jewish Federation and the president of the Retail Merchants Association. Because of his work as president of B’nai Zion for twenty-five years, the congregation later named him “Lifetime Honorary President.”

The Jews who remained continued to uphold their religious practices despite rapid migration off the island. Sidney Aronovitz, who graduated valedictorian from Key West High School in 1937 and went on to be a Federal Judge in Miami, remarked that, despite being the only Jew in his class, “Jews really integrated into the community without losing religious identity and fellowship.” The remaining Jews still worshiped together despite a frequent turnover in rabbinical leadership. Additionally, Pearlman, Charles Aronovitz, the Holtsbergs, and the Appels were among the Jewish merchants who continued to operate their shops in the 1930s.

The Jews who remained continued to uphold their religious practices despite rapid migration off the island. Sidney Aronovitz, who graduated valedictorian from Key West High School in 1937 and went on to be a Federal Judge in Miami, remarked that, despite being the only Jew in his class, “Jews really integrated into the community without losing religious identity and fellowship.” The remaining Jews still worshiped together despite a frequent turnover in rabbinical leadership. Additionally, Pearlman, Charles Aronovitz, the Holtsbergs, and the Appels were among the Jewish merchants who continued to operate their shops in the 1930s.

Regrowth and Centennial

The bar mitzvah of Mitchell Applerouth, 1948. State Archives of Florida.

The bar mitzvah of Mitchell Applerouth, 1948. State Archives of Florida.

As the Depression came to an end in the late 1930s, Key West’s small Jewish community continued to hold services at the converted doctor’s office. Although some years went by in the 1940s without a rabbi, B’nai Zion remained active throughout the mid-century. World War II brought in new military related industries to the island town, spurring a massive population boom, which included a number of new Jewish families. The congregation firmly rooted itself in the Conservative movement in the 1950s, but with a self-described “liberal slant.” The mid-century also saw Hebrew school numbers rise to more than fifty children, and by the late 1960s the congregation had outgrown the doctor’s office. In 1969, the community dedicated a newly built B’nai Zion synagogue on United Street, which included a modern, 250-seat sanctuary, a social hall with a kosher kitchen, a Hebrew school classroom, and a residence for the rabbi (who at the time was Rabbi Nathan Zwitman). Jack Einhorn, whose parents Annie and Abraham Einhorn were founding members of B’nai Zion near the turn of the century, oversaw the building of the new synagogue as president of the congregation. Einhorn remained president (as well as treasurer and secretary) for much of the rest of the century, and his wife, Rose Einhorn, served as president of the temple Sisterhood.

Jewish Conchs were not the only ones who helped to keep the temple running, however. Tourism was (and continues to be) just as important to B’nai Zion as it was to the rest of the island’s economy. As Key West’s population declined again in the distant wake of the war, the Jewish congregation again began to shrink. At the time of the congregation’s centennial in 1987, B’nai Zion was back down to 115 members, and six years later it had fallen to only 73 members. In order to support the synagogue, social hall, rabbi’s residence, and Hebrew school, the temple opened its doors to short-term vacationers, many of whom were surprised to find active Jewish life on the island. Tourists often took advantage of the temple’s open-door policy and attended Shabbat services and gave donations to the congregation. Some visitors enjoyed B’nai Zion so much that they returned to the temple for their wedding ceremony. B’nai Zion also began holding an annual brotherhood Shabbat service, attended by city officials, including the mayor and chief of police.

The 1990s also welcomed a new Jewish movement to Key West. In 1995, Chabad Jewish Center for the Florida Keys & Key West was founded by Rabbi Yaakov and Chanie Zucker, and in 2015, the center opened a mikvah, which immediately became a popular attraction among the Jews of Key West and tourists alike.

Jewish Conchs were not the only ones who helped to keep the temple running, however. Tourism was (and continues to be) just as important to B’nai Zion as it was to the rest of the island’s economy. As Key West’s population declined again in the distant wake of the war, the Jewish congregation again began to shrink. At the time of the congregation’s centennial in 1987, B’nai Zion was back down to 115 members, and six years later it had fallen to only 73 members. In order to support the synagogue, social hall, rabbi’s residence, and Hebrew school, the temple opened its doors to short-term vacationers, many of whom were surprised to find active Jewish life on the island. Tourists often took advantage of the temple’s open-door policy and attended Shabbat services and gave donations to the congregation. Some visitors enjoyed B’nai Zion so much that they returned to the temple for their wedding ceremony. B’nai Zion also began holding an annual brotherhood Shabbat service, attended by city officials, including the mayor and chief of police.

The 1990s also welcomed a new Jewish movement to Key West. In 1995, Chabad Jewish Center for the Florida Keys & Key West was founded by Rabbi Yaakov and Chanie Zucker, and in 2015, the center opened a mikvah, which immediately became a popular attraction among the Jews of Key West and tourists alike.

David Wolkowsky in front of Tony’s Fish Market, later the site of the Pier House restaurant, 1960s. State Archives of Florida.

David Wolkowsky in front of Tony’s Fish Market, later the site of the Pier House restaurant, 1960s. State Archives of Florida.

As tourism grew, Jews became deeply involved in the historic preservation of Key West. Mitchell Wolfson, the grand-nephew of the shipwrecked Joseph Wolfson in 1884, bought one of the oldest houses in the city and repaired it in the mid-20th century. In turn, he founded the Key West Historical Society to protect other historical landmarks. Moreover, Wolfson inspired a new generation of historic renovation projects. Ruth Holtsberg was a charter member of the Old Island Restoration Foundation, and David Wolkowsky, the grandson of Abraham Wolkowsky, led the effort for over 200 restoration projects on the island. Additionally, he founded Pirates Alley and the Pier House hotel and restaurant—a world-class resort in Key West—and became the southernmost homeowner in the continental United States after purchasing his own private island south of the city.

Anti-Semitism and Recovery

Key West’s Jewish community, which experienced little anti-Semitism in its 115-year Jewish history, became a target of sad and destructive acts during a three-month span in the early 21st century. In April, 2002, an arsonist poured five gallons of gasoline into B’nai Zion temple’s electrical room and lit it on fire. The fire destroyed the kitchen and damaged the social hall and sanctuary, but miraculously only inflicted minor smoke damage on the Torahs. Jewish and non-Jewish Key Westerners joined together support the B’nai Zion congregation. The Chabad house and St. Paul’s Episcopal Church offered their buildings as temporary sanctuaries and event spaces while the temple raised funds to repair the nearly one million dollars’ worth of damage. Other donors gifted siddurim, chumashim, and talleitot. Although a federal investigation stopped short of naming the arson a hate crime, members of the congregation believed that anti-Jewish sentiment was the underlying factor in the attack. This was all but confirmed just three months later when the Jewish section of the Key West Cemetery was vandalized and eight granite headstones were found broken. The Jewish and non-Jewish communities, angered and shocked that anti-Semitism would target the generally tolerant island town, again worked to repair the damage. Although the damage to the cemetery remains noticeable, the temple was fully restored thanks to the dedication of many dedicated volunteers.

The Jewish Community in Key West Today

As of 2018, the nearly 27,000-person island is almost entirely sustained by its tourist industry and has become a top destination for travelers seeking a tropical vacation. Although the Jewish shops on Duval street have closed their doors to make way for bars and gift shops (one of the last remaining Jewish shop was Appel’s Department Store, which continued to operate at its original location until the 1990s), other signs of Key West’s rich Jewish history still exist. In 2009, President Barack Obama signed a bill into law that renamed the U.S. Post Office, Custom House, and Courthouse in Key West the Sidney M. Aronovitz United States Courthouse, and an Aronovitz lane sits just a few blocks from the popular 0-mile marker of Route 1. Today, B’nai Zion and the Chabad Jewish Center continue to operate and welcome visitors. Although the Jewish population on the island is not nearly as large as it once was, many people are still deeply committed to growing and preserving South Florida’s oldest Jewish community. For over 130 years, Key West’s Jews have been integral parts of the city’s culture and economy, and in the words of long-time B’nai Zion president Jack Einhorn, “The history of Jews in Key West is, simply, the history of Key West… You can’t separate it.”

Selected Bibliography

Arlo Haskell, The Jews of Key West: Smugglers, Cigar Makers, and Revolutionaries (1823-1969), (Key West: Sand Paper Press, 2017).

Richard E. Sapon-White, “A Polish Jew on the Florida Frontier and in Occupied Tennessee: Excerpts from the Memoirs of Max White,” Southern Jewish History vol. 4, 2001, pp. 102-117.

Mtichell Wolfson, Sr., oral history conducted by Marcia Kanner, Nov. 24, 1970. Jewish Museum of Florida, Key West Files.

“Key West’s Jews: They’ll Mark 100 Years of Their Community,” The Jewish Floridian, May 15, 1987, pp. 12-A. “History of Congregation B’nai Zion”

Garry Boulard, “‘State of Emergency’: Key West in the Great Depression,” The Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 67, No. 2 (Oct., 1998), pp. 168-183.

Cara Buckley, “Synagogue begins repairs after arson,” Miami Herald, Sept 16, 2003.

Arlo Haskell, The Jews of Key West: Smugglers, Cigar Makers, and Revolutionaries (1823-1969), (Key West: Sand Paper Press, 2017).

Richard E. Sapon-White, “A Polish Jew on the Florida Frontier and in Occupied Tennessee: Excerpts from the Memoirs of Max White,” Southern Jewish History vol. 4, 2001, pp. 102-117.

Mtichell Wolfson, Sr., oral history conducted by Marcia Kanner, Nov. 24, 1970. Jewish Museum of Florida, Key West Files.

“Key West’s Jews: They’ll Mark 100 Years of Their Community,” The Jewish Floridian, May 15, 1987, pp. 12-A. “History of Congregation B’nai Zion”

Garry Boulard, “‘State of Emergency’: Key West in the Great Depression,” The Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 67, No. 2 (Oct., 1998), pp. 168-183.

Cara Buckley, “Synagogue begins repairs after arson,” Miami Herald, Sept 16, 2003.