Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - St. Petersburg, FL

Overview

Like many of Florida’s large cities today, St. Petersburg was a fairly small and isolated town for much of its pre-20th-century history. Across the bay from Tampa, it began to grow rapidly in the decades following the arrival of the railroad to the region and during the housing boom that occurred shortly thereafter. Jews were not a part of the “Sunshine City” population until after the turn of the 20th century, but quickly found difficulties upholding Jewish culture and integrating due to isolation from other Jews and a rampant anti-Semitism generated by the city’s non-Jewish population. It was not until 1923 that the first congregation was officially charted, far later than some other cities in the state. As time elapsed and the Jewish population grew in the post-World War Two era, anti-Semitism began to diminish, although not entirely. More Jewish intuitions opened in the waning decades of the century, and today Jews attend temples and synagogues of all sects in towns across Pinellas County.

Early Jews of St. Petersburg

Leon and Lillie Haliczer, early members of Congregation B’nai Israel, in 1925. State Archives of Florida.

Leon and Lillie Haliczer, early members of Congregation B’nai Israel, in 1925. State Archives of Florida.

Unlike its neighboring city, Tampa, which was incorporated as a military base before the Civil War, St. Petersburg did not receive official government recognition as a town until 1892. At that time, it likely had 300 residents, none of whom were known to be Jewish. By 1900, however, the U.S. Census lists the town as having over 1,500 residents, largely thanks to its wholesale fish business and its deep port for shipping goods.

The first known Jewish resident of St. Petersburg came from Germany in 1901 and opened a dry goods store on Central Avenue. Henry Schutz, whose store did not even have a cash register in its early days, quickly came to be a well-liked shop owner in the city. In December 1902, Schutz advertised on the front page of the Tampa Times for the “Christmas Goods” the store had stocked. Eight years later, the Times described Schutz as “one of our popular merchants,” and ran a column about his marriage to Emma Fleischman of Baltimore. Olga and Leon Manket arrived in 1908 to the city and opened another dry goods store on the same street, and Ben and Yetta Haliczer opened a gas station and tire store two years later.

At around the same time, other Jewish merchants began to settle in Tarpon Springs, north of St. Petersburg at the top of Pinellas Peninsula. The first Jew in Tarpon Springs was Sam Lovitz. One longtime resident recalled that his religion was known to the people of Tarpon Springs, noting that black workers in the town referred to Lovitz as “Mr. Jew Sam.” In 1913, he married Esther Tarapini, whose brother Abe had a store in St. Petersburg. To Abe, however, Tarpon Springs was “more thriving” than its southern neighbor, and he opened Tarapini’s Department Store there.

In St. Petersburg, the Jewish community remained fairly small before Florida’s massive land boom. In 1920, the Jewish families were the Schultzes, Mankets, Haliczers, Solomons, Sierkeses, Cohens, Katzes, Hellers, Hankins, and Schusters. Most of the Jewish children went to Mirror Lake High School and sat through Christian prayers. Likely because of the small size of the Jewish population, the group remained closely knit in these early years. Louis and Celia Cohen opened a bakery in 1920, which became a popular spot for Jews to hang out on Sundays while most of the city’s residents were in church. Another leisure activity was to drive the 45 miles on dirt roads around the northern edge of Tampa Bay (the first bridge across the bay, Gandy Bridge, was not completed until 1925) to go shopping in the much larger Tampa. One woman recalled that “Maas Brothers, in that city [Tampa], was the area’s only large department store owned by Jews. In St. Petersburg, Jews were still small merchants.”

The first known Jewish resident of St. Petersburg came from Germany in 1901 and opened a dry goods store on Central Avenue. Henry Schutz, whose store did not even have a cash register in its early days, quickly came to be a well-liked shop owner in the city. In December 1902, Schutz advertised on the front page of the Tampa Times for the “Christmas Goods” the store had stocked. Eight years later, the Times described Schutz as “one of our popular merchants,” and ran a column about his marriage to Emma Fleischman of Baltimore. Olga and Leon Manket arrived in 1908 to the city and opened another dry goods store on the same street, and Ben and Yetta Haliczer opened a gas station and tire store two years later.

At around the same time, other Jewish merchants began to settle in Tarpon Springs, north of St. Petersburg at the top of Pinellas Peninsula. The first Jew in Tarpon Springs was Sam Lovitz. One longtime resident recalled that his religion was known to the people of Tarpon Springs, noting that black workers in the town referred to Lovitz as “Mr. Jew Sam.” In 1913, he married Esther Tarapini, whose brother Abe had a store in St. Petersburg. To Abe, however, Tarpon Springs was “more thriving” than its southern neighbor, and he opened Tarapini’s Department Store there.

In St. Petersburg, the Jewish community remained fairly small before Florida’s massive land boom. In 1920, the Jewish families were the Schultzes, Mankets, Haliczers, Solomons, Sierkeses, Cohens, Katzes, Hellers, Hankins, and Schusters. Most of the Jewish children went to Mirror Lake High School and sat through Christian prayers. Likely because of the small size of the Jewish population, the group remained closely knit in these early years. Louis and Celia Cohen opened a bakery in 1920, which became a popular spot for Jews to hang out on Sundays while most of the city’s residents were in church. Another leisure activity was to drive the 45 miles on dirt roads around the northern edge of Tampa Bay (the first bridge across the bay, Gandy Bridge, was not completed until 1925) to go shopping in the much larger Tampa. One woman recalled that “Maas Brothers, in that city [Tampa], was the area’s only large department store owned by Jews. In St. Petersburg, Jews were still small merchants.”

The Birth of a Congregation

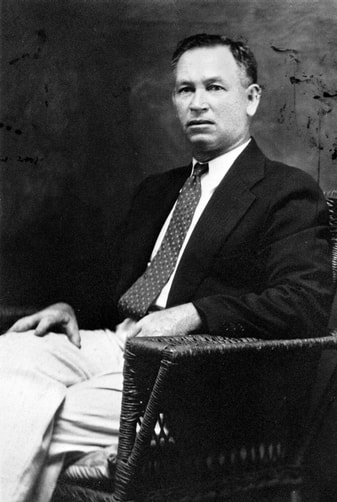

Hyman Jacobs, the first president of B’nai Israel. State Archives of Florida.

Hyman Jacobs, the first president of B’nai Israel. State Archives of Florida.

Keeping a Jewish identity required a strong will for the early Jewish families of the Sunshine City. In these early days—before the Gandy Bridge was built—getting kosher food was difficult for the Jews of St. Petersburg and Pinellas County. Kosher meat had to be shipped by boat from butchers in Tampa and often arrived spoiled. Community members kept up with Jewish news by subscribing to Yiddish newspapers like The Forward and Tageblatt. In order to provide Jewish education, parents organized a religious school and rented out the second floor of the Elks Club. Each Sunday, Rabbi Benedict of Temple Schaarai Zedek in Tampa took a boat across the bay in order to teach the children and lead prayer services. The first confirmation class graduated in 1922. For the High Holidays each year, St. Petersburg’s Jewish community travelled to Tampa for services.

By 1923, this group decided to officially become a chartered congregation. Twelve families met in a store on Central Avenue and formed Congregation B’nai Israel. The group chose Hyman Jacobs as its first president and Abe Sierkese as its first treasurer. They rented a former store on 13th Street North near 2nd Avenue North and held services there for the first three years of the congregation’s existence. Following his death in 1924, Wolf Katz became the first person to be buried in the Jewish section of Royal Palm Cemetery. In 1926, after outgrowing the storefront, the group rented out a former church on 9th Street and 9th Ave, hired its first part time rabbi, and started a cheder. Because many congregants could not afford to pay yearly dues, a member would walk around from store to store and collect 25 to 50 cents per week from the shop owners. To help those in need, Dora Goldberg organized the first women’s organization in the city, the Ladies Auxiliary.

By 1923, this group decided to officially become a chartered congregation. Twelve families met in a store on Central Avenue and formed Congregation B’nai Israel. The group chose Hyman Jacobs as its first president and Abe Sierkese as its first treasurer. They rented a former store on 13th Street North near 2nd Avenue North and held services there for the first three years of the congregation’s existence. Following his death in 1924, Wolf Katz became the first person to be buried in the Jewish section of Royal Palm Cemetery. In 1926, after outgrowing the storefront, the group rented out a former church on 9th Street and 9th Ave, hired its first part time rabbi, and started a cheder. Because many congregants could not afford to pay yearly dues, a member would walk around from store to store and collect 25 to 50 cents per week from the shop owners. To help those in need, Dora Goldberg organized the first women’s organization in the city, the Ladies Auxiliary.

Land Boom and Anti-Semitism

As the Jewish community began to organize in the early 1920s, two other important developments occurred in St. Petersburg. The first was the land boom, which drastically changed the landscape of the city. One resident recalls the excitement in the town during this period of rapid growth:

The boom years were exciting. It was as if a big door had swung open and hordes of people swarmed in. It reminded me of the Gold Rush days out West that I had read about. Single men and women, couples and familes [sic] arrived. Every empty store was soon occupied by a real estate office. They would stay open until midnight. Bands played in front of the shops giving it all a carnival atmosphere...

The Gandy Bridge, which connected Tampa and St. Petersburg, was the site of anti-Semitic signage during the 1920s. State Archives of Florida.

The Gandy Bridge, which connected Tampa and St. Petersburg, was the site of anti-Semitic signage during the 1920s. State Archives of Florida.

The city developed quickly, and newcomers arrived in such large numbers that the local government erected tents to temporarily house them. For the Jewish population, this meant that stores were doing well and new Jewish arrivals could easily find work.

The second new development was far worse for the Jews of St. Petersburg. The early 1920s saw a rampant rise in anti-Semitism. High ranking figures in the city made public statements about Jews and other immigrant groups. The secretary of the St. Petersburg Chamber of Commerce, for example, declared that “the time has come to make this a hundred percent American and gentile city as free from foreigners as from slums.” Many Jews were informed to not tell employers their religion if they worked for non-Jewish institutions, and some property deeds included restrictive covenants that stipulated they were “not to be sold to Jews” (others similarly said “not to be sold to Cubans). Many hotels and clubs began to restrict Jews, and ‘gentlemen’s agreements’ formed to discriminate Jews from the St. Petersburg Yacht Club and other civic groups.

Perhaps the most shocking, however, was that public signs were erected to directly discriminate against Jews. When the Gandy Bridge was completed in 1924, a car crossing toward St. Petersburg side would see a sign that read “No Jews Wanted Here.” Signs at resorts and restaurants that read “Restricted Clientele” or “Gentiles Only” reflected the exclusionary policies of many local institutions. Throughout much of the early and mid-century, the city was considered one of the most anti-Semitic in all of the United States.

Despite the bigotry and exclusion, however, the Jewish community did not react by forming “Jewish-only” groups (one columnist wrote that “that is an admission of defeat”) but instead by pushing back against the anti-Semitism or simply remaining quiet. Similarly, although Jews elsewhere were discouraged from coming and raising kids in St. Petersburg, many of the established Jewish merchants stayed in the city, even as the economy came crashing down later in the decade.

The second new development was far worse for the Jews of St. Petersburg. The early 1920s saw a rampant rise in anti-Semitism. High ranking figures in the city made public statements about Jews and other immigrant groups. The secretary of the St. Petersburg Chamber of Commerce, for example, declared that “the time has come to make this a hundred percent American and gentile city as free from foreigners as from slums.” Many Jews were informed to not tell employers their religion if they worked for non-Jewish institutions, and some property deeds included restrictive covenants that stipulated they were “not to be sold to Jews” (others similarly said “not to be sold to Cubans). Many hotels and clubs began to restrict Jews, and ‘gentlemen’s agreements’ formed to discriminate Jews from the St. Petersburg Yacht Club and other civic groups.

Perhaps the most shocking, however, was that public signs were erected to directly discriminate against Jews. When the Gandy Bridge was completed in 1924, a car crossing toward St. Petersburg side would see a sign that read “No Jews Wanted Here.” Signs at resorts and restaurants that read “Restricted Clientele” or “Gentiles Only” reflected the exclusionary policies of many local institutions. Throughout much of the early and mid-century, the city was considered one of the most anti-Semitic in all of the United States.

Despite the bigotry and exclusion, however, the Jewish community did not react by forming “Jewish-only” groups (one columnist wrote that “that is an admission of defeat”) but instead by pushing back against the anti-Semitism or simply remaining quiet. Similarly, although Jews elsewhere were discouraged from coming and raising kids in St. Petersburg, many of the established Jewish merchants stayed in the city, even as the economy came crashing down later in the decade.

Bust and Recovery

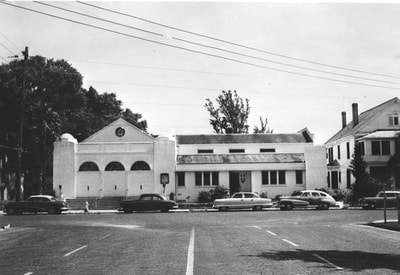

B’nai Israel Congregation, c. 1955. The left section of the building was constructed in 1935, with an addition added in 1950. State Archives of Florida.

B’nai Israel Congregation, c. 1955. The left section of the building was constructed in 1935, with an addition added in 1950. State Archives of Florida.

After 1925, the land boom was over. Many speculators and banks closed their doors and left as the housing bubble started to burst. The economy continued to decline and made no recovery as the Great Depression struck in 1929. Although much of the city’s population struggled with this new loss of industry, many of the early Jewish merchants who came in the early 1920s remained in St. Petersburg through the Depression. In fact, in 1928 a new congregation, Beth-El, formed as a Reform temple. Fortunately for St. Petersburg, the Works Progress Administration invested large sums of money for new projects, including the construction of a modern city hall. Through the 1930s, this helped to stimulate the economy and allowed for the city to recover.

Despite low funding, Congregation B’nai Israel was able to hire a new rabbi, S. C. Saltzman, in 1930. Throughout the decade, however, the synagogue went through at least five different ordained spiritual leaders. In 1935, they bought a lot on Arlington Avenue and built a new synagogue. Soon, they realized it was too small and purchased an adjoining lot to build a recreation hall.

Jewish occupational patterns began to shift in the 1930s as well. While most of the Jewish workers owned shops in the 1920s, the next decade saw a drastic rise in those who studied law. Many, including Eli and Ernie Katz, Morris Rosenberg, Irving Cypen, Jay Schwartz, Izzy Abrams and Ben Schwartz, moved to Miami, while other young lawyers branched out to other parts of the state and nation. In 1932, the first Jewish medical practice opened in St. Petersburg, owned by Dr. Louis B. Mount, a dermatologist. Other young Jewish adults became accountants, social workers, or other types of professionals.

Despite low funding, Congregation B’nai Israel was able to hire a new rabbi, S. C. Saltzman, in 1930. Throughout the decade, however, the synagogue went through at least five different ordained spiritual leaders. In 1935, they bought a lot on Arlington Avenue and built a new synagogue. Soon, they realized it was too small and purchased an adjoining lot to build a recreation hall.

Jewish occupational patterns began to shift in the 1930s as well. While most of the Jewish workers owned shops in the 1920s, the next decade saw a drastic rise in those who studied law. Many, including Eli and Ernie Katz, Morris Rosenberg, Irving Cypen, Jay Schwartz, Izzy Abrams and Ben Schwartz, moved to Miami, while other young lawyers branched out to other parts of the state and nation. In 1932, the first Jewish medical practice opened in St. Petersburg, owned by Dr. Louis B. Mount, a dermatologist. Other young Jewish adults became accountants, social workers, or other types of professionals.

The War Years and Growth

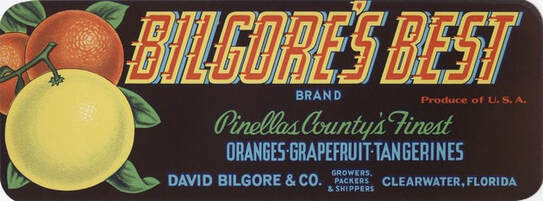

Jews in Clearwater and northern Pinnellas County, such as the Bilgore family, had been involved in agriculture and commerce for decades before the post-World-War-II boom spurred the organization of local congregations. University of Florida Digital Collections.

Jews in Clearwater and northern Pinnellas County, such as the Bilgore family, had been involved in agriculture and commerce for decades before the post-World-War-II boom spurred the organization of local congregations. University of Florida Digital Collections.

When the United States entered World War Two in 1941, St. Petersburg was still a relatively isolated city on the southern tip of Pinellas County. Elsewhere on the peninsula, vast tracts of untouched land opened doors for development and large scale production. The city’s population continued to skyrocket despite the depression, up 50 percent from 1930 to nearly 61,000. During the war, the St. Petersburg Times urged the U.S. government to invest in military jobs in and around the city, claiming that a government contract would be “tremendously helpful in maintaining economic stability and balance.” By 1942, 10,000 soldiers lived in St. Petersburg hotel rooms and on the new Pinellas Army Air Field, and by the next year nearly 70 city facilities had been allocated for use by the military. The Jewish community welcomed Jewish soldiers with public Shabbat dinners and Passover seders. Additionally, during the war, many Jewish doctors undertook their residency requirements at the Bay Pines Veterans Hospital on the eastern tip of Pinellas Peninsula. In the years following the Paris peace treaty, the Jewish population grew to an estimated 1,500.

The huge influx of Jews to St. Petersburg after the war led to the expansion of Jewish services in the city. Congregation B’nai Israel hired Rabbi Morris B. Chapman in 1947, affiliated itself with the United Synagogue of America (the Conservative movement) in 1949, and held its first bat mitzvah three years later. In 1950, the synagogue expanded to include a social hall, classrooms, a library, and, under the leadership of Rabbi Chapman, the award-winning Institute of Adult Studies. That same year, Sunday school—which was held jointly with Temple Beth-El—enrolled 125 students, up from 45 just four years earlier. Even more dramatically, by 1952, B’nai Israel’s congregation membership grew nearly fivefold from five years earlier. In 1953, members of St. Petersburg’s congregations joined together to form a Synagogue Council, which later became the Pinellas County Board of Rabbis. Six years later, the first Jewish nursery school opened. Outside of St. Petersburg, Jews began to organize congregations in Clearwater, which had been home to Jewish residents since the 1910s.

Temple Beth-El outgrew its cramped downtown location and in 1955 it moved to its current location on Pasadena Avenue South. Despite its previous expansions, by the end of the decade B’nai Israel’s synagogue also could not hold its growing congregation. Behind the fundraising efforts of board president Dr. Harold Rivkind, the congregation purchased land in 1958 on 59th Street North for a new synagogue and dedicated the building two years later. Also in 1960, a benevolent-minded group formed the Gulf Coast Jewish Family Services organization to help “infants, children, families and elders in serious physical, medical, mental, social and financial crisis.”

Still, anti-Semitism affected the Jewish community. Even in the post-war era, very few Jews had been allowed on the Chamber of Commerce committee, despite there being between 75 and 100 Jewish members of the Chamber and 3,100 Jews in the city. The most outwardly anti-Semitic publication in the city’s—and perhaps the nation’s—history was distributed in the 1960s. The National Christian News, the press arm of a seeming revival of the National Christian Party, outwardly blamed Jews for the world’s geo-political problems, as well as pinning the group for conspiracy, anti-Americanism, and even murder.

The huge influx of Jews to St. Petersburg after the war led to the expansion of Jewish services in the city. Congregation B’nai Israel hired Rabbi Morris B. Chapman in 1947, affiliated itself with the United Synagogue of America (the Conservative movement) in 1949, and held its first bat mitzvah three years later. In 1950, the synagogue expanded to include a social hall, classrooms, a library, and, under the leadership of Rabbi Chapman, the award-winning Institute of Adult Studies. That same year, Sunday school—which was held jointly with Temple Beth-El—enrolled 125 students, up from 45 just four years earlier. Even more dramatically, by 1952, B’nai Israel’s congregation membership grew nearly fivefold from five years earlier. In 1953, members of St. Petersburg’s congregations joined together to form a Synagogue Council, which later became the Pinellas County Board of Rabbis. Six years later, the first Jewish nursery school opened. Outside of St. Petersburg, Jews began to organize congregations in Clearwater, which had been home to Jewish residents since the 1910s.

Temple Beth-El outgrew its cramped downtown location and in 1955 it moved to its current location on Pasadena Avenue South. Despite its previous expansions, by the end of the decade B’nai Israel’s synagogue also could not hold its growing congregation. Behind the fundraising efforts of board president Dr. Harold Rivkind, the congregation purchased land in 1958 on 59th Street North for a new synagogue and dedicated the building two years later. Also in 1960, a benevolent-minded group formed the Gulf Coast Jewish Family Services organization to help “infants, children, families and elders in serious physical, medical, mental, social and financial crisis.”

Still, anti-Semitism affected the Jewish community. Even in the post-war era, very few Jews had been allowed on the Chamber of Commerce committee, despite there being between 75 and 100 Jewish members of the Chamber and 3,100 Jews in the city. The most outwardly anti-Semitic publication in the city’s—and perhaps the nation’s—history was distributed in the 1960s. The National Christian News, the press arm of a seeming revival of the National Christian Party, outwardly blamed Jews for the world’s geo-political problems, as well as pinning the group for conspiracy, anti-Americanism, and even murder.

1970s and 1980s

Temple B’nai Israel, Clearwater, was founded in 1949 and moved to their current site in 1972. Courtesy Temple B’nai Israel.

Temple B’nai Israel, Clearwater, was founded in 1949 and moved to their current site in 1972. Courtesy Temple B’nai Israel.

By the end of the 1960s, anti-Semitism seemed to be on the decline and the Jewish community continued to form new institutions. In 1970, B’nai Israel built Menorah Center, a subsidized senior citizens home, and that same year the congregation opened Menorah Gardens, a Jewish cemetery in Largo just north of St. Petersburg. Other towns in Pinellas County began to open their own temples and synagogues as well. In Clearwater, for example, a group of Jewish families had been meeting in private homes since 1957 under the name Congregation Beth Shalom, and officially opened their own Conservative synagogue in 1977 on South Belcher Road. (This building was replaced in 1992). Similarly, Reform Temple Ahavat Shalom opened in Palm Harbor in 1976, when the city was only connected to the Tampa Bay area by a two lane road. Other congregations include B’nai Emmunah in Tarpon Springs (Reform), Beth Shalom in Gulfport (Conservative), Congregation Aliyah in Clearwater (no longer in existence), and Temple B’nai Israel in Clearwater (Reform).

In 1980, Pinellas County Jewish Day School opened, serving 27 students in kindergarten, first, and second grades in its inaugural year. The school grew to serve more than 210 students from kindergarten through eighth grade by 2008, but financial hardships forced its closure in 2011. Subsequent attempts to found another Jewish school have not been successful. With the establishment of the day school in the 1980s, St. Petersburg and Pinelleas County offered Jewish institutions from nursery schools through retirement homes, and the only life-cycle-institution missing was a nursing home for the elderly. In 1985, Dr. Philip Benjamin was instrumental in founding Menorah Manor, which, at the time, was the only Jewish nursing home on the west coast of Florida. An independent, bi-weekly Jewish press opened to serve the region in 1986 called the Jewish Press of Pinellas County.

In 1980, Pinellas County Jewish Day School opened, serving 27 students in kindergarten, first, and second grades in its inaugural year. The school grew to serve more than 210 students from kindergarten through eighth grade by 2008, but financial hardships forced its closure in 2011. Subsequent attempts to found another Jewish school have not been successful. With the establishment of the day school in the 1980s, St. Petersburg and Pinelleas County offered Jewish institutions from nursery schools through retirement homes, and the only life-cycle-institution missing was a nursing home for the elderly. In 1985, Dr. Philip Benjamin was instrumental in founding Menorah Manor, which, at the time, was the only Jewish nursing home on the west coast of Florida. An independent, bi-weekly Jewish press opened to serve the region in 1986 called the Jewish Press of Pinellas County.

The Jewish Community in St. Petersburg Today

Since the start of the 21st century, St. Petersburg’s and Pinellas County’s Jewish community have continued to grow. The Florida Holocaust Museum, which moved to St. Petersburg’s museum district in 1998, continues to be a popular attraction for locals and visitors alike. In 2000, Congregation B’nai Israel again moved buildings, this time to 58th Street North. Beth-El added a religious school to the temple in 2002, at which time its full congregation was made up of 430 families. Chabad opened a new building in 2009, bringing a new sect of Judaism to the Sunshine City. Today, St. Petersburg is the fourth largest city in Florida, and despite its record of anti-Semitism, the Jewish citizens remain strong and committed to drawing in people of all ages to be part of a progressive and historical Jewish community.

Selected Bibliography

Raymond Arsenault, St. Petersburg and the Florida Dream, 1888-1950, (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2017).

Herman Koren, Histories of the Jewish People of Pinellas County, Florida, 1883-2005 / 5643-5766, (St. Petersburg: Temple B’nai Israel, 2007).

Jewish Museum of Florida, St. Petersburg files.

Goldie Jacobs Schusterer, “I Remember the Early Days of the Jewish Community of St. Petersburg Florida,” manuscript, n.d., Jewish Museum of Florida.

Raymond Arsenault, St. Petersburg and the Florida Dream, 1888-1950, (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2017).

Herman Koren, Histories of the Jewish People of Pinellas County, Florida, 1883-2005 / 5643-5766, (St. Petersburg: Temple B’nai Israel, 2007).

Jewish Museum of Florida, St. Petersburg files.

Goldie Jacobs Schusterer, “I Remember the Early Days of the Jewish Community of St. Petersburg Florida,” manuscript, n.d., Jewish Museum of Florida.