Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Orlando, FL

Overview

In Antebellum Florida, Euro-American settlers perceived the Orlando area as the line between the habitable north and inhospitable south. Where North Florida boasted St. Augustine, a 16th century Spanish settlement, and easier access to other Southern cities, South Florida promised pests, tropical disease, and physical isolation from the rest of the United States. With the exception of Key West, which achieved early success as a port and mercantile center, South-Central Florida, and particularly inland settlements such as Orlando, experienced slower development than their North Florida counterparts.

Yet those daring enough to venture southwards could find prosperity in Orlando—in its markets, citrus groves, and, eventually, in its looming tourist industry. The first Jews came to the Orlando area not long after the city’s 1875 incorporation and established themselves as merchants, farmers and ranchers or developers, restaurateurs, and hotel owners. A dramatic mid-century population boom spurred the continual development of organized Jewish life in the city and today the Greater Orlando area has one of the largest Jewish populations in Florida. Orlando’s Jewish history is regional and includes merchants, farmers, and early congregation members that span the Greater Orlando area, including in Orange County, Lake County, Osceola County, and Seminole County.

Yet those daring enough to venture southwards could find prosperity in Orlando—in its markets, citrus groves, and, eventually, in its looming tourist industry. The first Jews came to the Orlando area not long after the city’s 1875 incorporation and established themselves as merchants, farmers and ranchers or developers, restaurateurs, and hotel owners. A dramatic mid-century population boom spurred the continual development of organized Jewish life in the city and today the Greater Orlando area has one of the largest Jewish populations in Florida. Orlando’s Jewish history is regional and includes merchants, farmers, and early congregation members that span the Greater Orlando area, including in Orange County, Lake County, Osceola County, and Seminole County.

Early Orlando Jewish Life

In 1838 the United States founded Fort Gatlin just South of current-day Orlando, and by the 1880s settlers had moved in to form a small community around the Fort. During the Reconstruction Era, from 1865-1877, most Jewish settlers in Florida were peddlers or small-scale business owners, with the majority gravitating towards North Florida cities such as Gainesville, Jacksonville or Pensacola. Those migrating to Orlando after its 1875 incorporation took a risk on a less established frontier. Many Jewish families in the late 19th century “capitalized on kin” to start businesses and establish themselves in this unfamiliar territory.

Rose Kanner Friedman, 1921. Born in 1904, Rose was likely the first Jewish child born in Citrus County. State Archives of Florida.

Rose Kanner Friedman, 1921. Born in 1904, Rose was likely the first Jewish child born in Citrus County. State Archives of Florida.

The Kanner family is an example of this initial familial migration. In the late 1800s Zella Kanner and her husband, Frank Seligman, came from Romania and settled in Quincy, in the Florida Panhandle. Over the next twelve years, all seven of Zella Kanner’s siblings migrated to Florida, with a handful settling in Sanford, northeast of Orlando. Rose “Rosebud” Kanner was the first known Jewish child born in the Orlando area. By 1876 roughly nine Jewish families had moved to the Orlando area, reaching approximately a dozen in 1885. Early Jewish immigrants to Orlando were primarily of Prussian descent, or Romanian, like the Kanners. These Jewish settlers integrated smoothly on the Orlando frontier. In 1875 Jacob R. Cohen helped write the new city’s charter, and Orlando voters later elected Cohen alderman. In 1907, Rachel Kanner entered a hand-knit yarmulke in the Orange County Fair, unafraid to showcase her Judaism publicly.

In the late 1800s, Orlando’s citrus industry was in full-swing with a bust-boom cycle that characterized the history of citrus in Florida. The winters of 1894-1895 saw the first of several devastating freezes in the north of the state, where citrus farmers had historically concentrated. At the same time, railroad development in the late 19th century transformed the citrus industry, aiding a transition from local to statewide and national markets. Increased speed of delivery, as well as the advent of refrigerated train cars, decreased the chance of spoilage for shipping out-of-state. The advent of the railroad and the freezes that pushed citrus south, cemented Orlando as an important produce market. One of Orlando’s most successful citrus growers, Phillip “Doc” Phillips, arrived in 1897, purchasing a patch of groves that he would come to develop into 5,000 acres, and an operation that included housing, a post office, and even a cemetery for the workers he employed. Phillips had been born in Tennessee and, though reportedly of Jewish ancestry, guarded this aspect of his identity from the public. Though not a real doctor, Phillips later capitalized on his imagined medical background to campaign for the health benefits of Florida citrus.

The infrastructure changes that aided citrus benefited other produce industries as well. Early Jewish settlers to the Orlando area had mostly established themselves as small business owners in the downtowns of Orlando or surrounding communities. Now, some capitalized on new profitability in produce by taking on roles as farmers. In the late 19th century Moses Katz ran a grocery, hardware and clothing store in Kissimmee, Osceola County. Moses’ sons went into celery and cabbage growing, before continuing on in their father’s store, which was still in operation as of 2017. Henry and Sylvia Benedict, Prussian migrants, owned a dry goods store in Orlando in the late 19th century. They decided to leave their business to try their hands at pineapple packing. Though it is not clear how successful this venture was for the Benedicts, the packing business became a lucrative enterprise for a number of area Jews.

In the late 1800s, Orlando’s citrus industry was in full-swing with a bust-boom cycle that characterized the history of citrus in Florida. The winters of 1894-1895 saw the first of several devastating freezes in the north of the state, where citrus farmers had historically concentrated. At the same time, railroad development in the late 19th century transformed the citrus industry, aiding a transition from local to statewide and national markets. Increased speed of delivery, as well as the advent of refrigerated train cars, decreased the chance of spoilage for shipping out-of-state. The advent of the railroad and the freezes that pushed citrus south, cemented Orlando as an important produce market. One of Orlando’s most successful citrus growers, Phillip “Doc” Phillips, arrived in 1897, purchasing a patch of groves that he would come to develop into 5,000 acres, and an operation that included housing, a post office, and even a cemetery for the workers he employed. Phillips had been born in Tennessee and, though reportedly of Jewish ancestry, guarded this aspect of his identity from the public. Though not a real doctor, Phillips later capitalized on his imagined medical background to campaign for the health benefits of Florida citrus.

The infrastructure changes that aided citrus benefited other produce industries as well. Early Jewish settlers to the Orlando area had mostly established themselves as small business owners in the downtowns of Orlando or surrounding communities. Now, some capitalized on new profitability in produce by taking on roles as farmers. In the late 19th century Moses Katz ran a grocery, hardware and clothing store in Kissimmee, Osceola County. Moses’ sons went into celery and cabbage growing, before continuing on in their father’s store, which was still in operation as of 2017. Henry and Sylvia Benedict, Prussian migrants, owned a dry goods store in Orlando in the late 19th century. They decided to leave their business to try their hands at pineapple packing. Though it is not clear how successful this venture was for the Benedicts, the packing business became a lucrative enterprise for a number of area Jews.

Judaism in the Citrus Groves: Pittsburgh Migration

The Levy wedding, 1917. State Archives of Florida.

The Levy wedding, 1917. State Archives of Florida.

Between 1912 and 1913 a number of families, many of whom had pre-existing familial and social connections with each other, left their homes in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to become growers in the Orlando agrarian economy. These families were primarily of Russian descent and established themselves in citrus, as well as dairy and cattle ranching. Moses and Sarah Levy ventured to Florida as one of the first families to make the move, and in 1917 they held a wedding for their son Aaron in their citrus grove, using a Zionist flag as a chuppah. In the early 20th century, Jewish families gathered in the Levy groves for kosher picnics, and services led by Israel Shader, another member of the Pittsburgh migration.

Shader, an Orthodox, Russian immigrant, opened Fairvilla Dairy in 1913, near Lake Fairview—North of Orlando and in the same area as the Levy’s citrus farm. He may have been encouraged by information from his son-in law, Jacob Meitin, a grocer who resided with the Shader family in Pittsburgh and who may have caught wind of the citrus boom through his connections in the produce industry. Shader worked as a carpenter in Pittsburgh and thought it might be easier for his family to observe Jewish ritual in a new, agrarian setting. The Shader’s non-Jewish or less observant neighbors pitched in on Shabbat, milking the family’s cows. Shader regularly hosted the services held in the Levy grove for area Jewish families, but he never joined a formal congregation in Orlando, choosing instead to return to Pittsburgh for the High Holidays.

Shader, an Orthodox, Russian immigrant, opened Fairvilla Dairy in 1913, near Lake Fairview—North of Orlando and in the same area as the Levy’s citrus farm. He may have been encouraged by information from his son-in law, Jacob Meitin, a grocer who resided with the Shader family in Pittsburgh and who may have caught wind of the citrus boom through his connections in the produce industry. Shader worked as a carpenter in Pittsburgh and thought it might be easier for his family to observe Jewish ritual in a new, agrarian setting. The Shader’s non-Jewish or less observant neighbors pitched in on Shabbat, milking the family’s cows. Shader regularly hosted the services held in the Levy grove for area Jewish families, but he never joined a formal congregation in Orlando, choosing instead to return to Pittsburgh for the High Holidays.

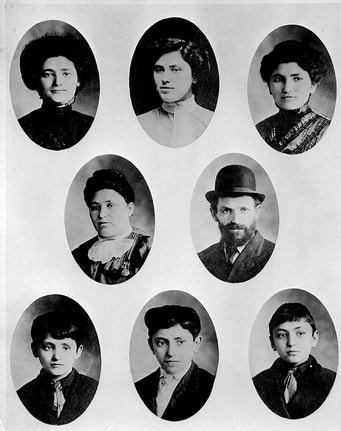

Israel and Rose Shader (center) and their children. State Archives of Florida.

Israel and Rose Shader (center) and their children. State Archives of Florida.

The Pittsburgh families maintained Jewish customs, such as following kashrut in part due to the skills offered by members of their community. While Israel Shader acted as a lay-leader for the community, David Wittenstein lent his skills as sofer, shochet, and mohel—roles he had received training for in his native Russia. As of the 1920s, Israel Shader’s son, Ben, reported keeping kosher and another member of the Pittsburgh migration, Jonas Cohen, ran a kosher butcher shop in the area.

Until the 1920s, growth in the citrus industry had put producers at a disadvantage with buyers and distributors. In 1922 lawmakers passed the Copper-Volstead Act, allowing cooperatives, like the Florida Citrus Exchange, to operate in exemption from antitrust laws. Cooperatives stabilized citrus prices to the benefit of producers and created cohesive marketing, which was particularly helpful given a pattern of surplus production in the 20th century. The late 1920s and early 1930s were economically difficult for the state, yet citrus growers still experienced the benefits of this legislation. While some Jewish populations in Florida cities—like Tallahassee, Pensacola, and Jacksonville—began to decline or plateau, Orlando’s Jewish population continued to grow.

Until the 1920s, growth in the citrus industry had put producers at a disadvantage with buyers and distributors. In 1922 lawmakers passed the Copper-Volstead Act, allowing cooperatives, like the Florida Citrus Exchange, to operate in exemption from antitrust laws. Cooperatives stabilized citrus prices to the benefit of producers and created cohesive marketing, which was particularly helpful given a pattern of surplus production in the 20th century. The late 1920s and early 1930s were economically difficult for the state, yet citrus growers still experienced the benefits of this legislation. While some Jewish populations in Florida cities—like Tallahassee, Pensacola, and Jacksonville—began to decline or plateau, Orlando’s Jewish population continued to grow.

Organized Jewish Life

Laying the cornerstone for Ohev Shalom, 1926. State Archives of Florida.

Laying the cornerstone for Ohev Shalom, 1926. State Archives of Florida.

In the early years of settlement, Orlando Jews worshipped informally in private homes and citrus groves. These early Jews experienced a level of integration that began decreasing with an influx of anti-Semitism during World War I. The Jewish population grew substantially with the addition of families from the Pittsburgh migration, becoming simultaneously more noticeable to the community and increasingly tight-knit. In 1918, a number of Orlando civic groups were in the midst of planning a rally around war bonds, when one member of the Jewish community, Pauline Berman, noted that no Jewish group had been invited to attend. Berman took this as a chance to gather with other members of the Jewish community and decided that it was time to establish a congregation.

A group of Orlando Jews founded Congregation Ohev Sholem (now Ohev Shalom) this same year. At first, congregants worshipped in a former church building on Central and Terry, in downtown Orlando. In 1926 the congregation built a new synagogue, on Eola and Church, installing a series of stained glass windows that nearly fifty-years later they would buy back from a developer to maintain in their third building. As the first, and for a time, only, synagogue in Orlando, Ohev Shalom was structured to accommodate Reform, Conservative and Orthodox members and continued this way until additional congregations formed in the 1940s and 1950. Charles Kanner donated the first Torah to Congregation Ohev Shalom, fitting given his long family history in the greater Orlando area.

Initially, Reverend Benjamin Safer travelled from Jacksonville on the High Holidays, while lay leaders led regular services. In the 1930s, Safer relocated to Orlando, becoming Ohev Shalom’s first full-time spiritual leader. A local B’nai Brith was chartered in 1926 and congregants founded the Ohev Shalom Cemetery—originally called Mount Neboh—in 1927, opening officially in 1928. The Torah that Israel Shader carried with him from Pittsburgh to Orlando was buried in the Ohev Shalom cemetery, even though Shader himself chose to be buried back in Pittsburgh. During the 1970s, Jewish families began relocating from downtown Orlando out towards the suburbs and the congregation followed suit. The third iteration of Ohev Shalom opened on Goddard Avenue, towards Lake Fairview, and in 2010 the congregation broke ground on a new campus in Maitland, also north of the city.

A group of Orlando Jews founded Congregation Ohev Sholem (now Ohev Shalom) this same year. At first, congregants worshipped in a former church building on Central and Terry, in downtown Orlando. In 1926 the congregation built a new synagogue, on Eola and Church, installing a series of stained glass windows that nearly fifty-years later they would buy back from a developer to maintain in their third building. As the first, and for a time, only, synagogue in Orlando, Ohev Shalom was structured to accommodate Reform, Conservative and Orthodox members and continued this way until additional congregations formed in the 1940s and 1950. Charles Kanner donated the first Torah to Congregation Ohev Shalom, fitting given his long family history in the greater Orlando area.

Initially, Reverend Benjamin Safer travelled from Jacksonville on the High Holidays, while lay leaders led regular services. In the 1930s, Safer relocated to Orlando, becoming Ohev Shalom’s first full-time spiritual leader. A local B’nai Brith was chartered in 1926 and congregants founded the Ohev Shalom Cemetery—originally called Mount Neboh—in 1927, opening officially in 1928. The Torah that Israel Shader carried with him from Pittsburgh to Orlando was buried in the Ohev Shalom cemetery, even though Shader himself chose to be buried back in Pittsburgh. During the 1970s, Jewish families began relocating from downtown Orlando out towards the suburbs and the congregation followed suit. The third iteration of Ohev Shalom opened on Goddard Avenue, towards Lake Fairview, and in 2010 the congregation broke ground on a new campus in Maitland, also north of the city.

Congregation Beth Israel of Sanford, also called the Jewish Community Center. State Archives of Florida.

Congregation Beth Israel of Sanford, also called the Jewish Community Center. State Archives of Florida.

Although Ohev Shalom is the oldest congregation in the greater Orlando area, others formed between the early and mid-20th century. Sanford’s Congregation Beth Israel was chartered in 1927 and operated in its own building until 1968. Sanford at one point had a notable Jewish population, having been the original home of several units of the Kanner family, but these numbers dwindled throughout the 20th century. Members of Congregation Beth Israel held meetings in private homes until 1997.

Congregation of Liberal Judaism—a Reform congregation that started in Orlando—developed a little later, in 1948. At first under the original name of the Liberal Jewish Fellowship, this group held services in the Ohev Shalom vestry, before laying the cornerstone for their own building in Winter Park in 1951. In 1958 there were 107 member families at the congregation and in 1963 they purchased their own section of the Woodlawn Cemetery in Gotha, Florida.

In 1954, forty families came together to found another Temple Israel, this one as a Conservative addition to Orlando’s Jewish community. Orlando’s Temple Israel began worshipping in a former downtown church in 1955 and moved further into the suburbs, with its congregants, throughout the 20th century. As of 2017, Temple Israel was located in a former Seventh Day Adventist building in Winter Park and maintained its own cemetery, which area developers Abe and Zelig Wise purchased after the founding of the congregation.

Congregation of Liberal Judaism—a Reform congregation that started in Orlando—developed a little later, in 1948. At first under the original name of the Liberal Jewish Fellowship, this group held services in the Ohev Shalom vestry, before laying the cornerstone for their own building in Winter Park in 1951. In 1958 there were 107 member families at the congregation and in 1963 they purchased their own section of the Woodlawn Cemetery in Gotha, Florida.

In 1954, forty families came together to found another Temple Israel, this one as a Conservative addition to Orlando’s Jewish community. Orlando’s Temple Israel began worshipping in a former downtown church in 1955 and moved further into the suburbs, with its congregants, throughout the 20th century. As of 2017, Temple Israel was located in a former Seventh Day Adventist building in Winter Park and maintained its own cemetery, which area developers Abe and Zelig Wise purchased after the founding of the congregation.

Third Wave of Jewish Migration: Merchants and Hospitality

Until the 1920s, Orlando Jews had arrived mainly in two distinct waves of migration—as Prussian or Romanian migrants who came as peddlers or merchants in the late 19th century, or as Russian Jews, many already established in the United States, who ventured south to capitalize on Orlando’s agrarian boom. Before World War II, Orlando saw a third wave of significant Jewish migration, marking the beginning of continual Jewish and overall population growth throughout the remainder of the 20th century. A number of the Jewish migrants arriving in the 1920s and 1930s opened successful shops, or established themselves in Orlando’s emerging tourism and hospitality industry. For example, In 1918 Ivan Burman, a Jewish Russian immigrant, moved with his wife Minnie and daughter Tybel from Ohio. Ivan started as a business owner, running Orlando Steam Laundry and in 1923, sensing the potential in hospitality, took out a 99-year lease on the previously established San Juan Hotel. His daughter, Tybel, became an important figure in the Gainesville Jewish community.

Sophie and Louis Kamenoff, 1925. State Archives of Florida.

Sophie and Louis Kamenoff, 1925. State Archives of Florida.

The Labellman family is another example of early, and long-lasting, successful Jewish merchants. Sarah Labellman and her family came to Orlando in 1919, having fled the pogroms in Ukraine. When her husband abandoned her and her seven children, she worked as a seamstress to support her family, often sewing fur on customers’ coats. Her son, Morris, opened La Belle Furs in Orlando after World War II, and the shop prospered. As of 2017, La Belle Furs was still open and in the process of being remodeled by the third generation of Labellmans. Other families experienced success as well. Louis and Sophie Kamenoff moved from South Carolina and opened a butcher shop in a local A & P in 1929. Louis was later a wholesaler for the Central Florida Bag Exchange.

From 1900 until 1960 approximately 200 Jewish merchants ran businesses in the Orlando area. Some merchants observed Sabbath, while others did not. Irving Gibbs, who opened Gibbs Louis Dress Shop in 1946 closed for Shabbat when others had abandoned the practicing of closing on Saturdays. Following the pattern of area congregations, throughout the 20th century merchants increasingly followed their clientele out from downtown towards the suburbs and malls.

From 1900 until 1960 approximately 200 Jewish merchants ran businesses in the Orlando area. Some merchants observed Sabbath, while others did not. Irving Gibbs, who opened Gibbs Louis Dress Shop in 1946 closed for Shabbat when others had abandoned the practicing of closing on Saturdays. Following the pattern of area congregations, throughout the 20th century merchants increasingly followed their clientele out from downtown towards the suburbs and malls.

Mid-Century Orlando

When World War II broke out in Europe in 1939, Jews only made up 25,000 members of Florida’s two million residents. However, post-War Florida experienced dramatic growth in its Jewish population, increasing from 25,000 in 1940 to 175,000 in 1960. Orlando during this era reflected the dramatic statewide Jewish population growth. At the same time that the city’s Jewish population grew, some social organizations in Orlando, such as the University Club and the local Country Club, still barred them from joining. Jews who were not as open about their heritage—such as famed citrus producer Phillip “Doc” Phillips—obtained entry to exclusive spaces, but growing numbers and a degree of social exclusion also encouraged mid-century Orlando Jews to form a variety of Jewish organizations.

Members of the 101 Club, 1934. State Archives of Florida.

Members of the 101 Club, 1934. State Archives of Florida.

In 1933 ten teenagers from Orlando High School started the “101 Club” in response to their exclusion from other social clubs. The name referred to the number ten, otherwise known as the number required to form a minyan. Jewish adults formed social groups around this same time, namely the Stag Club, for men, and the Doe Club, for women. Other groups—some more civically, politically or religiously minded—such as Hadassah and the Jewish Community Council formed mid-century. The Jewish community of Lake County established Congregation Beth Sholom of Lake County in 1954, drawing on the contribution of public funds in their community by Jews and non-Jews alike, and Congregation Beth Am of Longwood developed in 1975, as an alternative Conservative congregation.

Jews stuck together in a variety of recreational ways as well. In 1937 Ruth and Stanley Weinsier opened a “vegetarian health resort” near Orlando. Young Jewish couples enjoyed swimming, hayrides, and a bountiful organic garden at this popular destination. One summer the Weinsiers expanded by running Camp Bear Head at the resort, for local Jewish children. Jewish families clustered geographically, even as they made the move to the suburbs. In the 1960s Abe and Zelig Wise, of Wise Brothers Real Estate, developed the Palomar neighborhood, by Lake Fairview, where the Pittsburgh families had once held services in the citrus groves. Over fifty Jewish families moved to Palomar, which earned the nickname “The Golden Ghetto.”

Jews in Orlando had readier access to kosher foods than others in smaller Florida Jewish communities. During the early 20th century, Jewish community members had been able to observe kosher law by drawing on the skills of a shochet who had come with the Pittsburgh migration. A 1929 article in the Orlando Sentinel detailed what non-Jewish cooks can learn from kosher ones and declares the cuisine “wholesome, appetizing, and above all things, clean and pure.” This same article refers to kosher restaurants being “thronged by Gentiles” and includes recipes for Matzo Fritters and Prune Pie. Later in the century, a 1956 newspaper advertisement described the kosher options at Medinkowitz’s, with “prime meats directly from New York.” Run by Samuel and Esther Medinkowitz, this kosher meat shop and delicatessen was also a popular Jewish gathering space.

Jews stuck together in a variety of recreational ways as well. In 1937 Ruth and Stanley Weinsier opened a “vegetarian health resort” near Orlando. Young Jewish couples enjoyed swimming, hayrides, and a bountiful organic garden at this popular destination. One summer the Weinsiers expanded by running Camp Bear Head at the resort, for local Jewish children. Jewish families clustered geographically, even as they made the move to the suburbs. In the 1960s Abe and Zelig Wise, of Wise Brothers Real Estate, developed the Palomar neighborhood, by Lake Fairview, where the Pittsburgh families had once held services in the citrus groves. Over fifty Jewish families moved to Palomar, which earned the nickname “The Golden Ghetto.”

Jews in Orlando had readier access to kosher foods than others in smaller Florida Jewish communities. During the early 20th century, Jewish community members had been able to observe kosher law by drawing on the skills of a shochet who had come with the Pittsburgh migration. A 1929 article in the Orlando Sentinel detailed what non-Jewish cooks can learn from kosher ones and declares the cuisine “wholesome, appetizing, and above all things, clean and pure.” This same article refers to kosher restaurants being “thronged by Gentiles” and includes recipes for Matzo Fritters and Prune Pie. Later in the century, a 1956 newspaper advertisement described the kosher options at Medinkowitz’s, with “prime meats directly from New York.” Run by Samuel and Esther Medinkowitz, this kosher meat shop and delicatessen was also a popular Jewish gathering space.

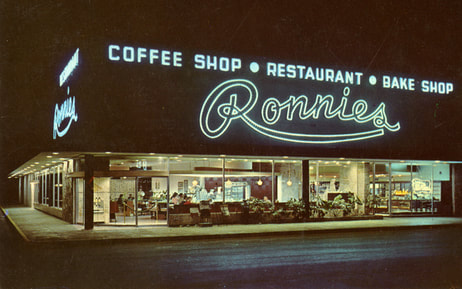

Ronnie’s, 1957. The restaurant, owned by Larry and Happy Leckart, was an Orlando institution for nearly 40 years. State Archives of Florida.

Ronnie’s, 1957. The restaurant, owned by Larry and Happy Leckart, was an Orlando institution for nearly 40 years. State Archives of Florida.

Jews ran non-kosher restaurants as well, a lucrative market as the city welcomed more tourists in the mid-century. Ronnie’s Restaurant operated as an Orlando institution from 1956 to 1995. Owned by Larry and Happy Leckart, customers knew the restaurant for its“rigid rules”—no food sharing and only two pats of butter per customer and for Larry Leckart’s constant station “his table,” where schmoozed with local politicians. In its years of operations, Ronnie served an estimated 4 million corned beef sandwiches.

Meanwhile, the produce industry continued to develop. By the 1930s and 1940s many Jews had become buyers and packers, in addition to vegetable and citrus growers. The citrus industry in particular boomed. Throughout the century, the losses from periodic crop freezes were counteracted by the invention of frozen concentrate orange juice, successful advertising campaigns and the development of cooperatives. As the citrus industry grew, so did Jews’ roles within it as opportunities abounded, from packing to irrigation and fertilizer research. Albert Morrel, a prominent area grower, became involved in aspects of citrus research and travelled to Israel in 1951 to advise the Israeli Ministry of Agriculture on citrus growing. In 1943, Ralph Meitin and Myer Shader, descendants of the Pittsburgh migration, teamed up to break from growing and establish Zellwood Fruit Distributors. Others, such as Seymour Lustig, focused on vertical integration, becoming produce “brokers” who paid the cost of purchasing, picking and packing so as to keep a larger portion of final sales.

The growth of both military presence and manufacturing continued to bring Jewish families to the area. During WWII McCoy Air Force Base operated only ten miles Southeast of the city. After the war, companies like Martin Company, which constructed missiles for Cape Canaveral, brought additional jobs to the area, continuing to spur development. 1958 saw the largest migration of Jewish scientists and engineers in the history of Central Florida. In 1971, Walt Disney World opened its doors for the first time, cementing the prosperity of Orlando’s tourism and hospitality market. Amira Cohen, a local Jewish resident who ran Amira’s restaurant from 1988 to 2009, provided her services as the first kosher caterer for the new tourist park. In the post-War population boom Congregation Ohev Shalom expanded its educational center to accommodate its 194 families.

From 1970 until the year 2000, the general Orlando population grew from 522,575 people to 1,644,561. Meanwhile, the Jewish population grew from roughly 2,500 Jews in the Orlando area in 1962 to 18,848 year-round Jewish residents in the region served by the Jewish Federation of Greater Orlando. As of 1993, the Greater Orlando area had the largest Florida Jewish population outside of the three-county Southeast region. Compared to these places, Orlando also had a relatively high percentage of local-born Jewish community members, indicating a level of familial continuity.

Meanwhile, the produce industry continued to develop. By the 1930s and 1940s many Jews had become buyers and packers, in addition to vegetable and citrus growers. The citrus industry in particular boomed. Throughout the century, the losses from periodic crop freezes were counteracted by the invention of frozen concentrate orange juice, successful advertising campaigns and the development of cooperatives. As the citrus industry grew, so did Jews’ roles within it as opportunities abounded, from packing to irrigation and fertilizer research. Albert Morrel, a prominent area grower, became involved in aspects of citrus research and travelled to Israel in 1951 to advise the Israeli Ministry of Agriculture on citrus growing. In 1943, Ralph Meitin and Myer Shader, descendants of the Pittsburgh migration, teamed up to break from growing and establish Zellwood Fruit Distributors. Others, such as Seymour Lustig, focused on vertical integration, becoming produce “brokers” who paid the cost of purchasing, picking and packing so as to keep a larger portion of final sales.

The growth of both military presence and manufacturing continued to bring Jewish families to the area. During WWII McCoy Air Force Base operated only ten miles Southeast of the city. After the war, companies like Martin Company, which constructed missiles for Cape Canaveral, brought additional jobs to the area, continuing to spur development. 1958 saw the largest migration of Jewish scientists and engineers in the history of Central Florida. In 1971, Walt Disney World opened its doors for the first time, cementing the prosperity of Orlando’s tourism and hospitality market. Amira Cohen, a local Jewish resident who ran Amira’s restaurant from 1988 to 2009, provided her services as the first kosher caterer for the new tourist park. In the post-War population boom Congregation Ohev Shalom expanded its educational center to accommodate its 194 families.

From 1970 until the year 2000, the general Orlando population grew from 522,575 people to 1,644,561. Meanwhile, the Jewish population grew from roughly 2,500 Jews in the Orlando area in 1962 to 18,848 year-round Jewish residents in the region served by the Jewish Federation of Greater Orlando. As of 1993, the Greater Orlando area had the largest Florida Jewish population outside of the three-county Southeast region. Compared to these places, Orlando also had a relatively high percentage of local-born Jewish community members, indicating a level of familial continuity.

Conclusion

The city that once was perceived as a line between the habitable and inhospitable has become a center of Florida Jewish life, exhibiting impressive generational continuity. As of 2017 the Greater Orlando area has seventeen synagogues, two community centers and eight kosher food establishments. As of 2018, the Shader family was on their fifth generation in in Orlando, having been in the area since 1913. The Lefkowitz’s, a family of “merchants and professionals,” are on their fourth generation, having been in the area since the 1920s, and La Belle Furs is still in operation its downtown location. While a number of citrus companies have moved south, one Jewish owned citrus packing company—Heller Bros. Packing Company—is run under fourth generation leadership in Winter Park. The company was founded by Isidore and Murry Heller in 1936.

Selected Bibliography

Henry Alan Green and Marcia Kerstein Zerivitz, Mosaic: Jewish Life in Florida (Mosaic, Inc. 1991).

Scott Hussey, “Freezes, Fights and Fancy: The Formation of Agricultural Cooperatives in the Florida Citrus Industry,” The Florida Historical Quarterly, 2010.

Kehillah: A History of Jewish Life in Greater Orlando, Orange County Regional History Center, 2017.

Mark Andrews, “19th Century Jewish Immigrants Succeeded Despite Discrimination,” Orlando Sentinel, 1998.

Ira M. Sheskin, The Jewish Federation of Greater Orlando Community Study, 1993.

Henry Alan Green and Marcia Kerstein Zerivitz, Mosaic: Jewish Life in Florida (Mosaic, Inc. 1991).

Scott Hussey, “Freezes, Fights and Fancy: The Formation of Agricultural Cooperatives in the Florida Citrus Industry,” The Florida Historical Quarterly, 2010.

Kehillah: A History of Jewish Life in Greater Orlando, Orange County Regional History Center, 2017.

Mark Andrews, “19th Century Jewish Immigrants Succeeded Despite Discrimination,” Orlando Sentinel, 1998.

Ira M. Sheskin, The Jewish Federation of Greater Orlando Community Study, 1993.