Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Jacksonville, FL

Overview

Jacksonville, located in Northeast Florida near the mouth of the St. Johns River, developed as a transportation hub between Florida and the rest of the United States by the mid-1800s. The city’s first known Jews arrived around the same time, and they organized some of Florida’s first Jewish institutions within a few decades.

As Jacksonville continued to grow in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it became home to the state’s largest Jewish community, with two congregations, a variety of Jewish organizations, and even a kosher butcher. Although Miami and South Florida overtook Jacksonville as the center of Florida Jewish life in the 1930s, Jacksonville’s Jewish population continued to grow steadily throughout the century. In the early 21st century, Jacksonville boasts a Jewish population of more than 10,000 individuals, and a robust network of Jewish communal organizations.

As Jacksonville continued to grow in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it became home to the state’s largest Jewish community, with two congregations, a variety of Jewish organizations, and even a kosher butcher. Although Miami and South Florida overtook Jacksonville as the center of Florida Jewish life in the 1930s, Jacksonville’s Jewish population continued to grow steadily throughout the century. In the early 21st century, Jacksonville boasts a Jewish population of more than 10,000 individuals, and a robust network of Jewish communal organizations.

Early Jews in Jacksonville

During the mid-19th century, Florida developed stronger links to the rest of the East Coast, spurred in large part by the establishment of regular rail and steamship travel, which arrived in Jacksonville from New York City via Savannah. From there, boats travelled to inland Florida on the St. Johns River.

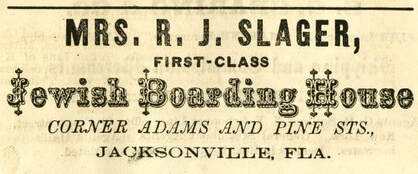

Ad for Mrs. R. J. Slager’s Jewish Boarding House, 1878. State Archives of Florida.

Ad for Mrs. R. J. Slager’s Jewish Boarding House, 1878. State Archives of Florida.

Jacksonville emerged as Florida’s largest trading hub by the time the territory gained statehood in 1845, and the city began to attract Jewish settlers in just a few years. The Dzialynski family arrived in 1853 after emigrating from Prussian Poland and living for a short time in New York City. The family consisted of Abraham Dzialynski and seven of his children—three sons and four daughters—whose ages ranged from approximately six to twenty. Within a few years, there were enough Jews in Jacksonville to gather for lifecycle events, such as the marriage of Philip Dzialynski to Ida Ehrlich in 1856 and the bris of their son George in 1857. The same year marked the beginning of Jewish organizational life in Jacksonville, as local Jews founded a cemetery around the same time that a yellow fever outbreak killed six of their coreligionists. The cemetery, a Jewish section in the Old City Cemetery was the first permanent Jewish organization to exist in the state of Florida.

When the American Civil War broke out in 1861, several Jacksonville Jews volunteered for the local Light Infantry Company of the Confederate Army. Despite early enthusiasm, however, a number of local Jews managed to avoid combat for part or all of the war. Isaac Ehrlich and Harris Burlack both escaped to Union territory rather than remain in the South or serve in the Confederate Army. Morris Dzialynski, who had moved with his family to Madison, Florida, around the beginning of the war, was wounded in action and later received a medical discharge. He took advantage of his subsequent role as a blockade runner to spend part of the war in New York City. He was married there in 1865 and returned to Jacksonville after the war. Available records do not show that Jacksonville Jews enslaved African Americans prior to the war.

Within a few years of the war, Morris Dzialynski became involved with the Democratic party and its efforts to “redeem” the South by ending Reconstruction and disenfranchising African American voters. In addition to owning a successful dry goods store, he was elected to city council in 1868 and served as mayor in the early 1880s. Upon his death in 1907, he was memorialized as a prominent citizen and Confederate veteran. While his brother-in-law Jacob Burkheim aligned himself with local white Republicans, both men’s daughters joined the United Daughters of the Confederacy in later years. Another Jewish Jacksonville resident, Philip Walter, held a series of local government positions and represented Duval County at the 1885 Florida Constitutional Convention, which suppressed the Black vote, outlawed interracial marriage, and instituted school segregation throughout the state.

When the American Civil War broke out in 1861, several Jacksonville Jews volunteered for the local Light Infantry Company of the Confederate Army. Despite early enthusiasm, however, a number of local Jews managed to avoid combat for part or all of the war. Isaac Ehrlich and Harris Burlack both escaped to Union territory rather than remain in the South or serve in the Confederate Army. Morris Dzialynski, who had moved with his family to Madison, Florida, around the beginning of the war, was wounded in action and later received a medical discharge. He took advantage of his subsequent role as a blockade runner to spend part of the war in New York City. He was married there in 1865 and returned to Jacksonville after the war. Available records do not show that Jacksonville Jews enslaved African Americans prior to the war.

Within a few years of the war, Morris Dzialynski became involved with the Democratic party and its efforts to “redeem” the South by ending Reconstruction and disenfranchising African American voters. In addition to owning a successful dry goods store, he was elected to city council in 1868 and served as mayor in the early 1880s. Upon his death in 1907, he was memorialized as a prominent citizen and Confederate veteran. While his brother-in-law Jacob Burkheim aligned himself with local white Republicans, both men’s daughters joined the United Daughters of the Confederacy in later years. Another Jewish Jacksonville resident, Philip Walter, held a series of local government positions and represented Duval County at the 1885 Florida Constitutional Convention, which suppressed the Black vote, outlawed interracial marriage, and instituted school segregation throughout the state.

Congregational Life

Following the Civil War, Jacksonville continued to serve as a major commercial hub for Florida, and its population grew rapidly, first in the 1860s and again in the 1880s. In 1867, local Jews began to hold religious services in the home of merchant Charles Slager. Three years later, an estimated 23 Jewish families lived in Jacksonville. By 1880, they had formed a Hebrew Benevolent Society and a B’nai Brith chapter, and the Jewish population reached approximately 130 individuals. Congregation Ahavath Chesed, the first Jewish congregation in Jacksonville and the second in the state, received its formal charter in 1882. The congregation soon built a synagogue in a Central European style that reflected many congregants’ geographic roots in Prussia and Germany. Although Ahavath Chesed grew steadily in its early years, Jacksonville Jews struggled to attract a long-term rabbi to their remote congregation, and six different clergy led the congregation between 1882 and 1900.

The bris of Joseph Safer, 1914.

Joseph was the son of Reverend Benjamin Safer, the first spiritual leader at B’nai Israel.

University of Florida George A. Smathers Libraries.

The bris of Joseph Safer, 1914.

Joseph was the son of Reverend Benjamin Safer, the first spiritual leader at B’nai Israel.

University of Florida George A. Smathers Libraries.

While Congregation Ahavath Chesed initially held traditional services, it affiliated with the Reform Movement in the 1890s. In response, five Jewish families began a new congregation that maintained Orthodox practices. They received their charter in 1901 as Hebrew Orthodox Congregation B’nai Israel. The congregation’s membership increased to 75 by 1905, and they purchased a cemetery lot that year. In 1909, Congregation B’nai Israel completed construction on a synagogue in the Lavilla neighborhood, where most Jewish newcomers lived and worked.

Reverend Benjamin Safer arrived to serve as the new group’s spiritual leader in 1901 or 1902. B’nai Israel members, primarily immigrants from Lithuania, had attempted to recruit Rabbi Joseph Shraga of Pokroy (Pakruojis), but he declined on account of his age. (Pokroy is about 15 miles from Pushelat, the hometown of many early B’nai Israel congregants.) Rabbi Shraga recommended his son Benjamin, however, who took the title “reverend” on account of his lack of official ordination. Reverend Safer led the congregation until 1912, but he made Jacksonville his permanent home. He served as the city’s first kosher butcher and mohel, and he continued to lead services at B’nai Israel when the synagogue was between rabbis.

Reverend Benjamin Safer arrived to serve as the new group’s spiritual leader in 1901 or 1902. B’nai Israel members, primarily immigrants from Lithuania, had attempted to recruit Rabbi Joseph Shraga of Pokroy (Pakruojis), but he declined on account of his age. (Pokroy is about 15 miles from Pushelat, the hometown of many early B’nai Israel congregants.) Rabbi Shraga recommended his son Benjamin, however, who took the title “reverend” on account of his lack of official ordination. Reverend Safer led the congregation until 1912, but he made Jacksonville his permanent home. He served as the city’s first kosher butcher and mohel, and he continued to lead services at B’nai Israel when the synagogue was between rabbis.

As the population of Jacksonville continued its rapid rise in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the city also became the largest Jewish center in the state, with an estimated 2,000 Jewish residents in the late 1910s. Among the Jewish newcomers were East European Jews, including a significant cohort from Pushelat (Pušalotas), Lithuania. This group consisted of several interrelated families, including the Finkelsteins, Schemers, and Slotts, who established a Pushelat landsmanshaft and contributed to the founding of B’nai Israel. New arrivals also came from smaller communities in Florida. Jacksonville’s larger and more organized Jewish community attracted the Weinkle family from Moffit and the Stein family from Lake City.

By 1900, Jacksonville had developed into a tourist destination as well as a trading hub, but the town experienced setbacks. A major yellow fever outbreak in 1888 infected over one-third of the city’s 13,000 residents and claimed more than 400 lives. The epidemic tempered growth and led some vacationers to select other Florida destinations (which were becoming increasingly accessible by rail). Then, in 1901, a major fire tore through downtown Jacksonville. The blaze destroyed more than 2,000 buildings and left 10,000 people without homes, and it remains the largest fire to occur in the American South.

By 1900, Jacksonville had developed into a tourist destination as well as a trading hub, but the town experienced setbacks. A major yellow fever outbreak in 1888 infected over one-third of the city’s 13,000 residents and claimed more than 400 lives. The epidemic tempered growth and led some vacationers to select other Florida destinations (which were becoming increasingly accessible by rail). Then, in 1901, a major fire tore through downtown Jacksonville. The blaze destroyed more than 2,000 buildings and left 10,000 people without homes, and it remains the largest fire to occur in the American South.

A Growing City

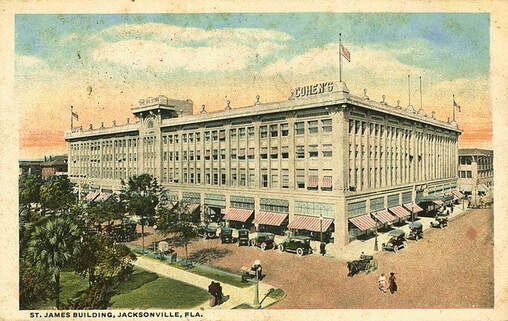

The St. James Building is an exemplar of the Prairie School style and housed the Cohen Brother’s Big Store for decades. University of Florida George A. Smathers Libraries.

The St. James Building is an exemplar of the Prairie School style and housed the Cohen Brother’s Big Store for decades. University of Florida George A. Smathers Libraries.

Jacksonville Jews both suffered from the destructive fire and contributed to the city’s recovery. Ahavath Chesed lost its synagogue but rebuilt another in the same style within a year. Herman Furchgott, a Jacksonville merchant since 1868, was the co-owner of Kohn-Furchgott’s Department Store, which had built a new, four-story building in 1900. After the business was destroyed in 1901, they rebuilt with a new store that ran the length of a full block on Main Street. The Cohen Brothers’ Big Store, which was known for modernizing the local retail trade, also burned in the fire. Under the leadership of Jacob Cohen, the firm constructed a four-story, 300,000-square-foot building that filled an entire block. Named the “St. James Building” after a hotel that previously occupied the site, the new store was among the ten largest department stores in the country. The St. James Building remained a department store until 1987 and has served as the Jacksonville City Hall since 1997.

The year after the fire, businessman Simon Benjamin moved with his family from Ocala to Jacksonville, where he contributed to the city’s recovery. Simon Benjamin also served as the president of Congregation Ahavath Chesed from 1911 to 1921. By the mid-1910s, his son Roy A. Benjamin began to leave his own mark on the city as a prominent architect. Roy Benjamin designed a number of significant landmarks from the 1910s to the 1940s, especially theaters. He also worked on the design for Jacksonville’s Memorial Park and became known as a leading Florida architect.

As Jacksonville continued to attract native-born and immigrant Jews in the early twentieth century, its Jewish organizations expanded and multiplied. Congregation Ahavath Chesed quickly outgrew its 1902 building and built a larger synagogue at the intersection of Laura and Ashley streets around 1910. Several newer organizations were based farther west, in the LaVilla neighborhood, where many of the East European newcomers settled. The Young Men’s Hebrew Association (Y.M.H.A.), established in 1914, served neighborhood Jews and stood across the street from the Orthodox synagogue B’nai Israel. Jewish immigrants in LaVilla also formed the core of the local Workmen’s Circle, which was founded in 1910 and operated a building down the street from the Y.M.H.A. in the 1920s. Local Jews established Zionist organizations during this period as well, including an affiliate of the Zionist Organization of America, founded in 1919.

The year after the fire, businessman Simon Benjamin moved with his family from Ocala to Jacksonville, where he contributed to the city’s recovery. Simon Benjamin also served as the president of Congregation Ahavath Chesed from 1911 to 1921. By the mid-1910s, his son Roy A. Benjamin began to leave his own mark on the city as a prominent architect. Roy Benjamin designed a number of significant landmarks from the 1910s to the 1940s, especially theaters. He also worked on the design for Jacksonville’s Memorial Park and became known as a leading Florida architect.

As Jacksonville continued to attract native-born and immigrant Jews in the early twentieth century, its Jewish organizations expanded and multiplied. Congregation Ahavath Chesed quickly outgrew its 1902 building and built a larger synagogue at the intersection of Laura and Ashley streets around 1910. Several newer organizations were based farther west, in the LaVilla neighborhood, where many of the East European newcomers settled. The Young Men’s Hebrew Association (Y.M.H.A.), established in 1914, served neighborhood Jews and stood across the street from the Orthodox synagogue B’nai Israel. Jewish immigrants in LaVilla also formed the core of the local Workmen’s Circle, which was founded in 1910 and operated a building down the street from the Y.M.H.A. in the 1920s. Local Jews established Zionist organizations during this period as well, including an affiliate of the Zionist Organization of America, founded in 1919.

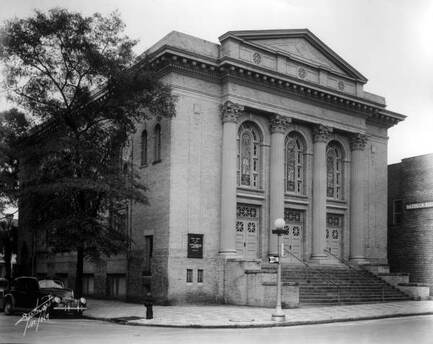

Congregation Ahavath Chesed, often known simply as “the Temple” built an imposing new synagogue in 1910, which they used until 1950. State Archives of Florida.

Congregation Ahavath Chesed, often known simply as “the Temple” built an imposing new synagogue in 1910, which they used until 1950. State Archives of Florida.

In addition to their increased population, Jacksonville Jews became more affluent in the 1910s and 1920s. Established department stores such as the Big Store and Kohn-Furchgott’s maintained their popularity, and newcomers found success with smaller retail stores and groceries in the rapidly growing city. Jacob Safer, Benjamin Safer’s brother, operated a kosher delicatessen near his brother’s butcher shop and the Orthodox synagogue in LaVilla during the 1910s. In the early 1920s, the family moved north to the newer, more upscale neighborhood of Springfield, and he began to work in real estate. Ben Setzer, one of the Pushelat immigrants, opened a grocery in 1925 that developed into a chain of 38 stores by the time he sold the business in 1958.

By the end of the 1920s, Jewish social and economic mobility also affected B’nai Israel, which joined the Conservative movement in 1926. Under the influence of Rabbi Samuel Benjamin, the congregation adopted the synagogue-center model of the time and changed its name to Jacksonville Jewish Center when it opened a new Springfield location in 1928. The Jewish Center attempted in early years to serve as a home for all local Jews, and it continued to operate B’nai Israel Synagogue as a downtown branch led by Reverend Benjamin Safer until 1930. In 1928 Ahavath Chesed opened a “Temple Home” in the affluent Riverside neighborhood, where it held social and educational functions.

By the end of the 1920s, Jewish social and economic mobility also affected B’nai Israel, which joined the Conservative movement in 1926. Under the influence of Rabbi Samuel Benjamin, the congregation adopted the synagogue-center model of the time and changed its name to Jacksonville Jewish Center when it opened a new Springfield location in 1928. The Jewish Center attempted in early years to serve as a home for all local Jews, and it continued to operate B’nai Israel Synagogue as a downtown branch led by Reverend Benjamin Safer until 1930. In 1928 Ahavath Chesed opened a “Temple Home” in the affluent Riverside neighborhood, where it held social and educational functions.

Economic Crises and World War II

Leaders of the Jacksonville Workmen’s Circle, c. 1949. The local branch was founded by young, radical immigrants in 1910, but membership declined precipitously by the late 1940s.

Leaders of the Jacksonville Workmen’s Circle, c. 1949. The local branch was founded by young, radical immigrants in 1910, but membership declined precipitously by the late 1940s.

At the close of the 1920s, Jacksonville boasted a Jewish population of at least 3,700. Depending on the estimate, as many as four out of ten Florida Jews lived in Jacksonville, and the figure was certainly more than one-third. Membership at Congregation Ahavath Chesed had surpassed 250 families. The late 1920s also brought statewide and national economic turbulence, however, and Miami’s rapidly growing Jewish community overtook Jacksonville’s as the largest in Florida by the early 1930s.

Florida’s economy suffered even before the advent of the Great Depression, with a hurricane, crop failures, and the collapse of the real estate market bringing the state’s 1920s boom years to an end. Jacksonville’s Jewish population held steady in the late 1920s and early 1930s, but the national economic crisis hindered the activities of local Jewish organizations. Agudath Achim lost about 140 dues paying families and had to disband its choir in 1930. The membership took years to recover. The Jacksonville Jewish Center, no longer able to pay a rabbi and a cantor, employed a single clergy member (first a cantor and then a rabbi) to serve the congregation. The local Workmen’s Circle, made up of less affluent immigrants, lost its building altogether, although they did manage to maintain their after school educational program well into the 1930s. Despite the challenges that local Jews faced during the Depression years, the relationship between Ahavath Achim and the Jacksonville Jewish Center improved during the period. Conservative Rabbi Morris Margolis arrived in 1932 and soon worked with the longtime Jacksonville Reform Rabbi, Israel Kaplan, to institute biannual joint services and to form the Jacksonville Jewish Community Council, a forerunner to the Jewish Federation of Jacksonville. At least one local Jewish family prospered during the depression, as Sam and Lou Wolfson turned a single 1933 scrap deal into a $100,000 windfall and established Florida Pipe and Supply. Lou became a millionaire by 1940, and his fortune grew with the acquisition of shipyards (and military contracts) in the 1940s. The Wolfson name eventually graced a number of Jacksonville institutions, including a high school, a baseball stadium, and a children’s hospital.

Jacksonville had hosted Jewish soldiers during World War I, when the army build Camp Johnson to the south of the city, and both synagogues had provided hospitality to servicemen at the time. When the United States entered World War II in 1941, Jacksonville became a significant military hub once again, with both the Army’s Camp Blanding and the Jacksonville Naval Air Station nearby. (The Naval Air Station was built at the former site of Camp Johnson.) Local Jewish organizations helped to organized social events and religious services for Jewish service members from other parts of the country, and a number of sailors and soldiers decided to settle permanently in Jacksonville after the war. The presence of so much military activity contributed to a general economic recovery and population surge in Jacksonville, as well. Alexander Brest, a Boston-born Jew who had been stationed in Jacksonville during World War I, had founded Duval Engineering and Contracting Company during the 1920s. The company landed construction contracts at the Naval Air Station and other military facilities during the war. Brest amassed a fortune through these and other government contracts, and he later owned television stations and became a major benefactor of Jacksonville University and other local institutions.

Florida’s economy suffered even before the advent of the Great Depression, with a hurricane, crop failures, and the collapse of the real estate market bringing the state’s 1920s boom years to an end. Jacksonville’s Jewish population held steady in the late 1920s and early 1930s, but the national economic crisis hindered the activities of local Jewish organizations. Agudath Achim lost about 140 dues paying families and had to disband its choir in 1930. The membership took years to recover. The Jacksonville Jewish Center, no longer able to pay a rabbi and a cantor, employed a single clergy member (first a cantor and then a rabbi) to serve the congregation. The local Workmen’s Circle, made up of less affluent immigrants, lost its building altogether, although they did manage to maintain their after school educational program well into the 1930s. Despite the challenges that local Jews faced during the Depression years, the relationship between Ahavath Achim and the Jacksonville Jewish Center improved during the period. Conservative Rabbi Morris Margolis arrived in 1932 and soon worked with the longtime Jacksonville Reform Rabbi, Israel Kaplan, to institute biannual joint services and to form the Jacksonville Jewish Community Council, a forerunner to the Jewish Federation of Jacksonville. At least one local Jewish family prospered during the depression, as Sam and Lou Wolfson turned a single 1933 scrap deal into a $100,000 windfall and established Florida Pipe and Supply. Lou became a millionaire by 1940, and his fortune grew with the acquisition of shipyards (and military contracts) in the 1940s. The Wolfson name eventually graced a number of Jacksonville institutions, including a high school, a baseball stadium, and a children’s hospital.

Jacksonville had hosted Jewish soldiers during World War I, when the army build Camp Johnson to the south of the city, and both synagogues had provided hospitality to servicemen at the time. When the United States entered World War II in 1941, Jacksonville became a significant military hub once again, with both the Army’s Camp Blanding and the Jacksonville Naval Air Station nearby. (The Naval Air Station was built at the former site of Camp Johnson.) Local Jewish organizations helped to organized social events and religious services for Jewish service members from other parts of the country, and a number of sailors and soldiers decided to settle permanently in Jacksonville after the war. The presence of so much military activity contributed to a general economic recovery and population surge in Jacksonville, as well. Alexander Brest, a Boston-born Jew who had been stationed in Jacksonville during World War I, had founded Duval Engineering and Contracting Company during the 1920s. The company landed construction contracts at the Naval Air Station and other military facilities during the war. Brest amassed a fortune through these and other government contracts, and he later owned television stations and became a major benefactor of Jacksonville University and other local institutions.

Postwar Boom

Jacksonville’s wartime emergence as a military and industrial center led to continued growth in the immediate postwar years, and the city’s population reached 200,000 people by 1950. The Jewish population rose from approximately 3,000 individuals in 1946 to an estimated 4,000 in 1954. The growth came primarily from out-of-state transplants, especially American born Jews from the urban Northeast. Despite the influx of newcomers, the Jewish community only accounted for 1.3% of the local population in 1954, nothing like the Jewish population explosion taking place in the Miami area during the same years.

Both Ahavath Chesed, known colloquially as The Temple, and the Jacksonville Jewish Center expanded during these years. The Temple constructed a new building in Riverside in 1950 and planned an expansion by the end of the decade. The Center developed a wider array of programming during the 1940s and embarked on a series of improvements to and expansions of its Springfield site during the 1950s. Both congregations brought in new leadership as well. The Temple’s Rabbi Sidney Lefkowitz served from 1946 to 1973 and was known as a popular and civic-minded leader, while Rabbi Sanders Tofield led the Center from 1947 until his untimely death in 1960. Rabbi Tofield brought a strong reputation for scholarship as well as a clear vision for the synagogue center project, and he was a prominent leader in the Conservative movement’s Rabbinical Assembly of America. A third Jacksonville congregation came into being in 1946, when a small group of Center members split off to establish Orthodox congregation Etz Chaim. The creation of Etz Chaim corresponded to the Center’s ongoing trajectory away from its Orthodox roots and toward mainstream Jewish Conservatism.

Both Ahavath Chesed, known colloquially as The Temple, and the Jacksonville Jewish Center expanded during these years. The Temple constructed a new building in Riverside in 1950 and planned an expansion by the end of the decade. The Center developed a wider array of programming during the 1940s and embarked on a series of improvements to and expansions of its Springfield site during the 1950s. Both congregations brought in new leadership as well. The Temple’s Rabbi Sidney Lefkowitz served from 1946 to 1973 and was known as a popular and civic-minded leader, while Rabbi Sanders Tofield led the Center from 1947 until his untimely death in 1960. Rabbi Tofield brought a strong reputation for scholarship as well as a clear vision for the synagogue center project, and he was a prominent leader in the Conservative movement’s Rabbinical Assembly of America. A third Jacksonville congregation came into being in 1946, when a small group of Center members split off to establish Orthodox congregation Etz Chaim. The creation of Etz Chaim corresponded to the Center’s ongoing trajectory away from its Orthodox roots and toward mainstream Jewish Conservatism.

The Setzer’s grocery chain spread well beyond Jacksonville by mid-century and helped launch the career of attorney and developer Lonnie Wurn. State Archives of Florida.

The Setzer’s grocery chain spread well beyond Jacksonville by mid-century and helped launch the career of attorney and developer Lonnie Wurn. State Archives of Florida.

Along with numerical growth, the Jacksonville Jewish community shifted geographically in the mid-20th century. While nearly three-fourths of Jacksonville Jews lived in Riverside or Springfield in 1946, over half had crossed the St. Johns River to Southside by 1954. The southward migration continued in ensuing decades, and both the Temple and the Synagogue moved to developing Southside neighborhoods by the end of the 1970s. Jacksonville’s suburban expansion, which led to the consolidation of the city with Duval County in 1968, also provided business opportunities for local Jews. Lonnie Wurn immigrated to Jacksonville from Poland as a child and attended the University of Florida. He married Emily Bloom in the 1930s and began to work as an attorney for the Setzer family, relatives of Emily’s father. By the 1940s Wurn had acquired enough capital to go into the residential construction industry, and the family became a significant force in the subsequent development of suburban Jacksonville.

The southward drift of Jacksonville Jews occurred during a period of transition for the city, as national events and local Black activists challenged the status quo of white supremacy. Jacksonville had been dominated by the Jim Crow system for decades, and area Jews had largely adjusted to local practices of segregation and discrimination. A history of the Jacksonville Jewish Center notes that segregation played a role in the departure of Rabbi David Panitz in the 1940s, due to his family’s “inability… to adjust to living in a segregated southern community.” When the Jacksonville Jewish Center received slight damage from a dynamite blast in April 1958—on the same night as a more effective attack on a local all-Black elementary school—the Center’s administrative director expressed shock that the congregation would be a target. “The subject [of integration] has never even come up in our congregation,” he reportedly said. The bombings had been accompanied by threatening phone calls from a segregationist and anti-Semitic group that identified itself as the “Confederate Underground.” Rabbi Lefkowitz, of the Temple, did develop a reputation for supporting desegregation through his work with the Urban League and the Human Relations Council. According to local histories, these activities drew backlash from some members of the congregation. Still, Jacksonville Jews were likely more supportive of Black civil rights than white non-Jews. Mary Singleton, whose 1972 election made her the first African American since Reconstruction to represent North Florida in the state legislature, credited Jewish support for some of her political success.

The southward drift of Jacksonville Jews occurred during a period of transition for the city, as national events and local Black activists challenged the status quo of white supremacy. Jacksonville had been dominated by the Jim Crow system for decades, and area Jews had largely adjusted to local practices of segregation and discrimination. A history of the Jacksonville Jewish Center notes that segregation played a role in the departure of Rabbi David Panitz in the 1940s, due to his family’s “inability… to adjust to living in a segregated southern community.” When the Jacksonville Jewish Center received slight damage from a dynamite blast in April 1958—on the same night as a more effective attack on a local all-Black elementary school—the Center’s administrative director expressed shock that the congregation would be a target. “The subject [of integration] has never even come up in our congregation,” he reportedly said. The bombings had been accompanied by threatening phone calls from a segregationist and anti-Semitic group that identified itself as the “Confederate Underground.” Rabbi Lefkowitz, of the Temple, did develop a reputation for supporting desegregation through his work with the Urban League and the Human Relations Council. According to local histories, these activities drew backlash from some members of the congregation. Still, Jacksonville Jews were likely more supportive of Black civil rights than white non-Jews. Mary Singleton, whose 1972 election made her the first African American since Reconstruction to represent North Florida in the state legislature, credited Jewish support for some of her political success.

Late 20th Century

While the Center and the Temple both purchased Southside land during the 1960s, the first congregation to fully relocate across the river was actually a Conservative offshoot of the Center, Beth Shalom Congregation. Beth Shalom began with 13 families—some of whom had been with the Center for generations—who left to form a new congregation in 1972. The group first met in an empty furniture store in a Southside mall, though they began construction on their own synagogue in 1974. Beth Shalom was known for adopting egalitarian practices before the Center and for its interfaith activities. Rabbi Gary Perras served the congregation from 1974 to 2001. By 2011, Beth Shalom’s membership had dwindled, and they re-merged with the Jacksonville Jewish Center.

River Garden Hebrew Home, Jacksonville’s Jewish senior center, joined other Jewish institutions on the Southside in 1989. The home grew out of the work of the Ladies’ Hebrew Sheltering Aid Society and originally occupied a Riverside mansion, which was expanded and renovated over the decades until it reached a capacity of 192 residents in the late 1960s. As of 2019, River Garden Senior Services occupies a 40-acre campus in the Mandarin area which offers a variety of services and houses 180 residents. The Jacksonville Jewish Community Alliance, a Federation-affiliated community center, also opened on the Southside in 1988.

As in other cities, Jewish occupational patterns in Jacksonville also changed in the second half of the 20th century. The major Jewish department stores either closed or sold out to chains, and downtown no longer served as a major shopping district. Rosenblum’s, a men’s wear store founded by Frank Rosenblum in 1898, opened a series of locations in the city under the leadership of Rosenblum’s sons. In 1981, they closed the downtown store, but two of Frank Rosenblum’s grandsons still run two branches of the business as of 2019—one in Southside and another in Jacksonville Beach. Another family retail business, French Novelty, has been in business since 1911, but left downtown for the suburbs in the 1960s. Originally founded by Salim Mizrahi, who was born in Ottoman ruled Lebanon, the company once owned dozens of stores under three names in Jacksonville and other Florida cities. By 2019 the chains had contracted to a single location, which specializes in dresses and gowns for weddings, proms and quinceanera celebrations. By the 1980s, fewer local Jews made their living as small business owners, and more had moved into corporate management and the professions.

While Jewish life in Jacksonville generally moved to the Southside by 1990, a rising Jewish population on the coast led to the formation of Beth El (Reform), which bills itself as “the Beaches Synagogue.” The congregation’s founders organized in the early 1990s, and it draws membership primarily from the Jacksonville Beach area. By the end of the century, Jacksonville was also home to a branch of the Chabad Lubavitch movement, which bases its Northeast Florida operations out of the Mandarin area as of 2019.

Although growth and success primarily characterized the close of the 20th century for Jacksonville’s Jewish community, one disturbing incident in the 1990s stands out. In February 1997, an Orthodox Jewish man, Harry Shapiro, planted a pipe bomb at the Jacksonville Jewish Center in advance of a speech by former Israeli Prime Minister Shimon Peres. Shapiro then called 911 to deliver a bomb threat, hoping to disrupt the appearance by Peres, who had played a pivotal role in peace negotiations with the Palestine Liberation Organization and a treaty agreement with Jordan. After a search for the explosive device failed, the event went on. The bomb did not detonate, and it was discovered by children nine days later. Harry Shapiro turned himself in to police. He pleaded guilty to one charge and received a ten-year prison sentence.

River Garden Hebrew Home, Jacksonville’s Jewish senior center, joined other Jewish institutions on the Southside in 1989. The home grew out of the work of the Ladies’ Hebrew Sheltering Aid Society and originally occupied a Riverside mansion, which was expanded and renovated over the decades until it reached a capacity of 192 residents in the late 1960s. As of 2019, River Garden Senior Services occupies a 40-acre campus in the Mandarin area which offers a variety of services and houses 180 residents. The Jacksonville Jewish Community Alliance, a Federation-affiliated community center, also opened on the Southside in 1988.

As in other cities, Jewish occupational patterns in Jacksonville also changed in the second half of the 20th century. The major Jewish department stores either closed or sold out to chains, and downtown no longer served as a major shopping district. Rosenblum’s, a men’s wear store founded by Frank Rosenblum in 1898, opened a series of locations in the city under the leadership of Rosenblum’s sons. In 1981, they closed the downtown store, but two of Frank Rosenblum’s grandsons still run two branches of the business as of 2019—one in Southside and another in Jacksonville Beach. Another family retail business, French Novelty, has been in business since 1911, but left downtown for the suburbs in the 1960s. Originally founded by Salim Mizrahi, who was born in Ottoman ruled Lebanon, the company once owned dozens of stores under three names in Jacksonville and other Florida cities. By 2019 the chains had contracted to a single location, which specializes in dresses and gowns for weddings, proms and quinceanera celebrations. By the 1980s, fewer local Jews made their living as small business owners, and more had moved into corporate management and the professions.

While Jewish life in Jacksonville generally moved to the Southside by 1990, a rising Jewish population on the coast led to the formation of Beth El (Reform), which bills itself as “the Beaches Synagogue.” The congregation’s founders organized in the early 1990s, and it draws membership primarily from the Jacksonville Beach area. By the end of the century, Jacksonville was also home to a branch of the Chabad Lubavitch movement, which bases its Northeast Florida operations out of the Mandarin area as of 2019.

Although growth and success primarily characterized the close of the 20th century for Jacksonville’s Jewish community, one disturbing incident in the 1990s stands out. In February 1997, an Orthodox Jewish man, Harry Shapiro, planted a pipe bomb at the Jacksonville Jewish Center in advance of a speech by former Israeli Prime Minister Shimon Peres. Shapiro then called 911 to deliver a bomb threat, hoping to disrupt the appearance by Peres, who had played a pivotal role in peace negotiations with the Palestine Liberation Organization and a treaty agreement with Jordan. After a search for the explosive device failed, the event went on. The bomb did not detonate, and it was discovered by children nine days later. Harry Shapiro turned himself in to police. He pleaded guilty to one charge and received a ten-year prison sentence.

Jewish Jacksonville in the 21st Century

A 2002 study by demographer Ira Sheskin showed a population of more than 8,000 Jews living in the “core” Jacksonville area and an additional 1,900 or so living in The Beaches. In 2009, the Orthodox Union recognized Jacksonville as an “emerging community” that might appeal to Orthodox Jews interested in moving out of larger Jewish centers and seeking a lower cost of living. Some local Orthodox Jews questioned the designation noting that Jacksonville was not home to a private Jewish high school. While Jacksonville has not emerged as a hotbed of Jewish Orthodoxy and does not support a Jewish high school as of 2019, there are two Jewish schools that offer elementary and middle school curriculums. Overall, the Jewish community has developed steadily with the city, offering a full range of Jewish cultural programming and social services. Furthermore, Jewish religious life remains fairly centralized, with the three historical synagogues in Jacksonville proper representing the three major denominations of American Judaism.

Selected Bibliography

The Temple, Avahath Chesed, Congregation Anniversary History, 1882-1957, available through University of Florida Digital Collections.

Henry Alan Green and Marcia Zerivitz, Mosaic: Jewish Life in Florida (Mosaic Inc., 1991).

Philip N. Selber, “The History of the Jacksonville Jewish Center, 1901 to 1960,” manuscript.

Ira Sheskin, 2002 Jacksonville Jewish Community Study, available through jewishdatabank.org.

Stephen Whitfield, “Commerce and Community,” Southern Jewish History, vol. 12, 2009.

Daniel Weinfeld, “A Certain Ambivalence: Florida’s Jews and the Civil War,” Southern Jewish History, vol. 17, 2014.

Jewish Jacksonville, online exhibit, George A. Smathers Libraries, University of Florida.

The Temple, Avahath Chesed, Congregation Anniversary History, 1882-1957, available through University of Florida Digital Collections.

Henry Alan Green and Marcia Zerivitz, Mosaic: Jewish Life in Florida (Mosaic Inc., 1991).

Philip N. Selber, “The History of the Jacksonville Jewish Center, 1901 to 1960,” manuscript.

Ira Sheskin, 2002 Jacksonville Jewish Community Study, available through jewishdatabank.org.

Stephen Whitfield, “Commerce and Community,” Southern Jewish History, vol. 12, 2009.

Daniel Weinfeld, “A Certain Ambivalence: Florida’s Jews and the Civil War,” Southern Jewish History, vol. 17, 2014.

Jewish Jacksonville, online exhibit, George A. Smathers Libraries, University of Florida.