Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Lakeland, FL

This history of Jewish life in Lakeland and Polk County has benefited from the advice and assistance of local expert Dr. Catherine Eskin, Associate Professor of English at Florida Southern College and curator of the Temple Emanuel Archive.

Overview

Lakeland sits at the western edge of Polk County in Central Florida, and although Lakeland and nearby Winter Haven are sometimes counted as part of greater Tampa, the area has its own Jewish history, which dates back to the early 20th century. Prior to that, European settlements in the area began in the mid-1800s and grew slowly until the arrival of railroad lines in the 1880s. A handful of Jews may have lived in and around Polk County prior to 1900, but the current community traces its roots to Cy Wolfson’s arrival in 1909. In the following decades, Lakeland developed a small but active Jewish community which attracted participants from a number of surrounding towns and continues to serve the local Jewish population in the early 21st century.

Early Jewish Settlers

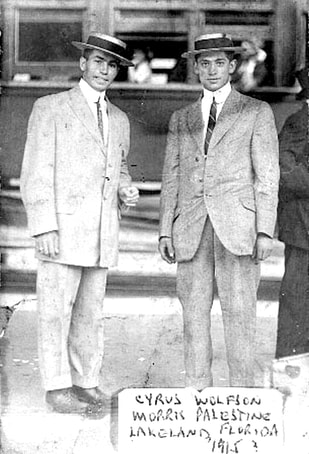

Cyrus Wolfson (left) with brother-in-law Morris Palestine, c. 1915. State Archives of Florida.

Cyrus Wolfson (left) with brother-in-law Morris Palestine, c. 1915. State Archives of Florida.

By 1909, Polk County and Lakeland had grown sufficiently to attract the attention of a young Jewish peddler, Cyrus (Schneir) Wolfson. Wolfson, born in Lithuania, had immigrated to New York City in 1899. He traveled to Ocala on business in 1909 and visited Lakeland while traveling around the state. Wolfson saw an opportunity in Lakeland and decided to start a business on North Kentucky Avenue. He also peddled dry goods by buggy and by train in the surrounding communities, either as a supplement to his storefront or before its establishment. According to local histories, Cy stayed for three years but wavered on whether to remain in the small town, then home to approximately 3,700 of Polk County’s 24,000 residents. He reportedly discussed his dilemma with the owner of the boarding house where he lived, indicating that he was lonely as the only Jewish immigrant in town. (There were other Jewish merchants in the area, but they do not seem to have stayed long.) The boarding house owner responded, “well, young man, someone must be the first. If you don’t stay and start your people, who will?” Not long after, Wolfson traveled back to New York, where he made arrangements to settle permanently in Lakeland. He also wed “long-time acquaintance Frances Palestine” on the trip, and they started a family the next year.

When Frances Wolfson moved to Lakeland with Cy in 1912, their home lacked indoor plumbing and the town’s roads were not yet paved. As a result of the town’s rustic conditions—and in line with common practice at the time—she opted to return to New York for the birth of their first child, Jack, in 1913. A doctor had moved to town by the time their second son, Joshua Herbert, was born in 1914, however, and he was born at the family home. A third son, Wilfred, followed in 1917. As the family grew, so did Lakeland, and the town began to pave roads, add street lighting, and install residential gas lines during the Wolfson family’s early years. Cy and Frances became accepted members of the white, middle-class community; he was an early member of several fraternal organizations, including the Masons and Shriners, and she was involved with the Order of the Eastern Star, an auxiliary organization to the Masons. Then, in 1920, they opened a larger business, the Famous Department Store, across the street from Munn Park in downtown.

When Frances Wolfson moved to Lakeland with Cy in 1912, their home lacked indoor plumbing and the town’s roads were not yet paved. As a result of the town’s rustic conditions—and in line with common practice at the time—she opted to return to New York for the birth of their first child, Jack, in 1913. A doctor had moved to town by the time their second son, Joshua Herbert, was born in 1914, however, and he was born at the family home. A third son, Wilfred, followed in 1917. As the family grew, so did Lakeland, and the town began to pave roads, add street lighting, and install residential gas lines during the Wolfson family’s early years. Cy and Frances became accepted members of the white, middle-class community; he was an early member of several fraternal organizations, including the Masons and Shriners, and she was involved with the Order of the Eastern Star, an auxiliary organization to the Masons. Then, in 1920, they opened a larger business, the Famous Department Store, across the street from Munn Park in downtown.

Organized Jewish Life

By 1920, other Jewish families had moved to surrounding towns, including Mulberry, Winter Haven, Lake Wales, and Fort Meade. Notable among the new arrivals were the Schneider, Brodes, and Goldman families, who were connected by siblings Philip and Harry Brodes, Bessie Schneider, and Rose Goldman. The adults (including the Brodes siblings) were typically born in the 1880s or 1890s in the Russian Empire, had lived in the urban North before moving to Florida, and operated dry goods or clothing stores. Although the Jewish immigrants often spoke Yiddish among themselves, they did not teach it to their American-born children. By the mid-1920s, local Jews began to hold prayer services, first in private homes and then in rented facilities, and they began to organize religious school classes not long after. While lay members led most religious services, they received monthly visits from Rabbi L. Elliot Grafman of Tampa, who also assisted with religious education. As Jews continued to migrate to the area, Lakeland emerged as the center of Jewish life. Between 1932 and 1934, the small group of 16 families purchased a small building and formally organized as the Lakeland Jewish Alliance.

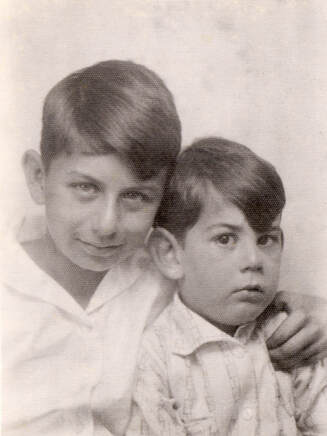

Melvin and Selig Estroff, c. 1930. Temple Emanuel Archives.

Melvin and Selig Estroff, c. 1930. Temple Emanuel Archives.

The fledgling congregation received an “influx” of Jewish migrants shortly after its founding. Among the newcomers were the families of cousins Joseph and Nat Wolf. Nat and his wife, Mollie, came to the area in 1936 after moving from New Jersey and purchasing an orange grove in Lake Garfield (in central Polk County). They bought an additional grove in Sebring with Nat’s brother Joe in 1938, and Joe Wolf helped to conduct services and organize the congregational choir in that period. Another early lay leader for the congregation was Harry Slakman, a Russian-born store owner who moved to Lakeland from Georgia by 1934.

Not long after the Lakeland Jewish Alliance bought their first building, the community celebrated its first bar mitzvah ceremony, that of Melvin Estroff (born 1920 in Lyons, Georgia). Melvin and his younger brother, Selig, were both “put on the bus” to study Hebrew with a rabbi in Tampa, who then came to Lakeland to perform the ceremonies. Melvin and Selig’s parents, Sam and Tillie, had lived in Lakeland since the mid-1920s and were joined in the area by friends and relatives from Georgia.The Estroff brothers also received instruction from their grandfather, Harris Estroff of Plant City.

Not long after the Lakeland Jewish Alliance bought their first building, the community celebrated its first bar mitzvah ceremony, that of Melvin Estroff (born 1920 in Lyons, Georgia). Melvin and his younger brother, Selig, were both “put on the bus” to study Hebrew with a rabbi in Tampa, who then came to Lakeland to perform the ceremonies. Melvin and Selig’s parents, Sam and Tillie, had lived in Lakeland since the mid-1920s and were joined in the area by friends and relatives from Georgia.The Estroff brothers also received instruction from their grandfather, Harris Estroff of Plant City.

Temple Emanuel

The Jewish community of Lakeland and Polk County grew and become more organized in the late 1930s and early 1940s. They changed their name to Temple Emanuel and began the search for a full-time rabbi, hiring Rabbi Jack Friedman in 1943. Rabbi Friedman, like many of his successors, only stayed in Lakeland for a short time, but Temple Emanuel’s membership continued to increase. World War II brought a number of Jewish military service members to the area, and local Jewish families hosted soldiers in their homes for holidays and social occasions. In the early 1940s, the Temple Emanuel Sisterhood also helped to bring a German refugee family to Lakeland: Hugo Goldsmith, his wife Reta, and daughter Ruth. Ruth finished high school in Lakeland, married Paul Weitzenkorn (also born in Germany), and raised a family in Lakeland while the couple owned a retail store in Winter Haven.

By the late 1940s, the Jewish community had outgrown the original Lakeland Jewish Alliance building. Rabbi Alexander Gelberman, who served Temple Emanuel from 1948 to 1955, and congregation president Sam Siegel, of Haines City, led the campaign for a new facility that would fulfill the congregation’s needs and could accommodate future additions. Temple Emanuel soon purchased an old brick mansion from Florida Southern College and converted the second story into a sanctuary. Harry Blumberg, a founding member of the congregation, served as the general contractor for the renovation process, which was completed in 1949. The home was located on Lake Hollingsworth, a prestigious section of town, and surrounded by orange groves. During Rabbi Gelberman’s tenure the congregation also affiliated with the Conservative movement, celebrated its first bat mitzvah, and established its own cemetery, about five miles southeast of the synagogue.

Social and Civic Life

The Jewish community of Lakeland and Polk County was, for the most part, well accepted in the mid-twentieth century. Jewish business owners belonged to civic and professional groups, including Rotary, Elks, Chamber of Commerce, and the Downtown Development Association. In addition to retail stores and citrus farms, local Jews owned pharmacies, sold home appliances and farm equipment, practiced law and medicine, and worked in the restaurant supply business. Melvin Estroff, co-owner with his brother of the Empire stores, was involved in a variety of civic and charitable causes in the 1960s and served as a founding member of the Lakeland Human Relations Council, which advocated for African American Civil Rights and economic opportunities. In the arena of local sports, department store owner Reuben Miller held a controlling share of the Lakeland Pilots minor-league baseball franchise in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

While the Jewish community generally projected an air of respectability, individual members were involved in a handful of scandals. Prominent businessman Harry Blumberg was convicted of tax evasion in the 1950s and paid a $20,000 fine after a lengthy legal process that was widely reported in area newspapers. Blumberg had been involved in controversy before, having been charged with insurance related arson in 1932 (the charges were dropped). In 1942, a Federal judge rejected Blumberg’s petition for citizenship over questions of “moral fitness,” which stemmed mostly from his paint and glass business’s involuntary bankruptcy in 1933. A former member of the Lakeland Jewish community, Esther Roth, even testified against Blumberg at the hearing, claiming that “he didn’t care what he did to his fellow man so long as he could get riches.” Another Lakeland Jewish resident, Herman Slakman, was found guilty of arson in the late 1960s, after the drugstore that he co-owned burned down in 1966.

It is not clear whether the Blumberg or Slakman incidents precipitated negative feelings about the Jewish population in general, but local Jews did face social barriers in the 1950s and 1960s. Jewish children raised in Lakeland in the early and mid-twentieth century were often the only Jews in their classes. Oral histories and memoirs tell stories of being asked to sing Christian hymns and recite bible verses in school or (less commonly) of other kids asking to see their horns. Additionally, elite social clubs excluded Jews, most notably the Lakeland Yacht Club, which reportedly accepted only white, male, Christian members until the 1980s. (Jews did visit the club as guests, and Jewish wedding receptions took place there in the 1940s and 1950s.)

Children participate in the Temple Emanuel groundbreaking, 1962. Temple Emanuel Archives.

Children participate in the Temple Emanuel groundbreaking, 1962. Temple Emanuel Archives.

Perhaps the clearest expression of anti-Jewish sentiment came in 1959, when prominent Lakeland residents attempted to derail Temple Emanuel’s plans for a new synagogue building. The congregation had grown to more than 250 households in 1956, and they developed a plan to construct a new, modern building between the converted house and the lakeshore. They intended to keep the mansion for youth activities. When Temple Emanuel announced the proposed project in May 1959, however, they faced an unexpected backlash. Over the next five months, the Zoning Board dragged its feet in approving the construction, despite a standing ordinance and numerous precedents allowing houses of worship in residential neighborhoods. In the meantime, a petition against the synagogue circulated among Lakeland’s elite, eventually gathering an estimated 150 signatures. According to community histories, each signer was a member of the Lakeland Yacht Club, located not far from Temple Emanuel on Lake Hollingsworth, and they opposed the new synagogue ostensibly for its non-residential appearance and potential effect on property values. Local Jews persisted, in spite of this opposition, and public opinion turned in their favor after the local newspaper published a letter by the minister of the First Presbyterian Church that decried the synagogue opposition movement as anti-Semitic. The Zoning Board unanimously approved the project in November 1959, and construction took place in 1962.

A Mature Jewish Community

By the early 1960s, Temple Emanuel served as the centerpiece for visible and established Jewish community that, like the populations of Lakeland and Polk County, had grown considerably over the previous two decades. In addition to congregational life, local Jews had participated in B’nai B’rith and Hadassah since the 1940s, and they coordinated philanthropic work through the Polk County Federation of Jewish Charities. The community also developed an active chapter of the United Synagogue Youth that participated in regional events beginning in the 1950s. Yet the community remained small, especially compared to Tampa, Orlando, or the booming Jewish center of South Florida. Lakeland’s relative size probably explains the continued rabbinical turnover during the 1950s and 1960s. After Rabbi Gelberman took another position in 1955, Temple Emanuel employed a series of clergy for terms of two to five years, until Rabbi Herman Gorod began an eight-year term in 1969.

In the meantime, the congregation lost its mansion, then in use as an education building, to a fire in spring 1964. That fall they broke ground on an up-to-date Educational Youth Center, completed in 1965. Over the next decade or so, Temple Emanuel paid off its mortgage and added stained glass windows to its sanctuary and boardroom. In the late 1970s, the community instituted full religious equality for women, including full Saturday morning bat mitzvah ceremonies for girls, counting women in the minyan, and granting them the honor of aliyot. In 1981, Temple Emanuel hired a second religious leader, Norman Golner, who took on educational and cantorial duties.

For nearly fifty years, Temple Emanuel was the only Jewish congregation in Polk County, and it drew members from other cities and nearby counties, as well. Families in other towns included the Friedlanders in Fort Wales and the Weiners in Wauchula (Hardee County), who drove their children nearly 40-miles each way to attend religious school during the 1960s. The Kahn family and other Jews in Sebring (Highland County) also held memberships at the Lakeland synagogue. Temple Emanuel’s run as the sole synagogue in Polk County ended in 1982, when a handful of young Jewish families organized Temple Beth Shalom, a Reform congregation based in Winter Haven. Initially, they hosted monthly Friday evening Shabbat services and holiday observances. Within a few years, Temple Beth Shalom opened its own religious school with fifteen students. The congregation purchased land for a synagogue in the early 1990s, obtained its own cemetery section later that decade, and completed construction on their own synagogue in 2003. They have employed part-time rabbis throughout their existence.

For nearly fifty years, Temple Emanuel was the only Jewish congregation in Polk County, and it drew members from other cities and nearby counties, as well. Families in other towns included the Friedlanders in Fort Wales and the Weiners in Wauchula (Hardee County), who drove their children nearly 40-miles each way to attend religious school during the 1960s. The Kahn family and other Jews in Sebring (Highland County) also held memberships at the Lakeland synagogue. Temple Emanuel’s run as the sole synagogue in Polk County ended in 1982, when a handful of young Jewish families organized Temple Beth Shalom, a Reform congregation based in Winter Haven. Initially, they hosted monthly Friday evening Shabbat services and holiday observances. Within a few years, Temple Beth Shalom opened its own religious school with fifteen students. The congregation purchased land for a synagogue in the early 1990s, obtained its own cemetery section later that decade, and completed construction on their own synagogue in 2003. They have employed part-time rabbis throughout their existence.

Late 20th and 21st Centuries

Polk County’s Jewish population did not sustain its mid-twentieth-century growth into the 1970s. Whereas Temple Emanuel had approximately 250 member families in 1956, a 1979 newspaper article referred to a membership of “about 200” households. The children of merchants often left for college and did not return. Small retail shops depended on the success of local agriculture, and they faced increasing competition from malls and larger chain stores in the 1970s and 1980s. As the older generation retired or moved away, the local Jewish community drew increasingly from professional occupations, especially in law and medicine. As of 2019, the last remaining Jewish owned retail store in downtown Lakeland is Nathan’s Men’s Store, originally opened by Samuel Estroff’s brother Nathan in 1942 and operated by his son Harris.

Despite these changes, Polk County’s Jewish population remained relatively stable, with an estimated 1,000 Jews in the area in the mid-1990s. As of 2019, both Temple Emanuel and Beth Shalom hold regular services. Temple Emanuel holds Friday evening and Saturday morning minyans, employs a full-time rabbi, and has twenty or more children enrolled in religious school. Temple Beth Shalom holds services twice monthly. Although they do not run a religious school, the congregation has hosted four b’nai mitzvot ceremonies since 2017. As Jewish life in Polk County continues, local Jews have also taken the initiative to document the area’s Jewish past through the Temple Emanuel Archive, which are managed by Dr. Catherine Eskin, an English professor at Florida Southern College.

Despite these changes, Polk County’s Jewish population remained relatively stable, with an estimated 1,000 Jews in the area in the mid-1990s. As of 2019, both Temple Emanuel and Beth Shalom hold regular services. Temple Emanuel holds Friday evening and Saturday morning minyans, employs a full-time rabbi, and has twenty or more children enrolled in religious school. Temple Beth Shalom holds services twice monthly. Although they do not run a religious school, the congregation has hosted four b’nai mitzvot ceremonies since 2017. As Jewish life in Polk County continues, local Jews have also taken the initiative to document the area’s Jewish past through the Temple Emanuel Archive, which are managed by Dr. Catherine Eskin, an English professor at Florida Southern College.

Selected Bibliography

Elisa Albo, “The Atlas of My Memory,” blog post, Bridges to/from Cuba, Dec. 31, 2016.

Catherine R. Eskin, “‘A Nice Little Community of Jews’: Tillie Estroff, Motherhood, and the Latest from Lakeland, 1925,” Polk County Historical Quarterly, April 2008.

James V. Holton, “‘If You Don’t Start Your People, Who Will?’ The Wolfsons—Lakeland’s Pioneer Jewish Family,” Polk County Historical Quarterly, September 2002.

Jewish Museum of Florida, Lakeland Files

Elisa Albo, “The Atlas of My Memory,” blog post, Bridges to/from Cuba, Dec. 31, 2016.

Catherine R. Eskin, “‘A Nice Little Community of Jews’: Tillie Estroff, Motherhood, and the Latest from Lakeland, 1925,” Polk County Historical Quarterly, April 2008.

James V. Holton, “‘If You Don’t Start Your People, Who Will?’ The Wolfsons—Lakeland’s Pioneer Jewish Family,” Polk County Historical Quarterly, September 2002.

Jewish Museum of Florida, Lakeland Files