Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - South Florida, FL

Overview

South Florida—Palm Beach, Broward, and Miami Dade Counties—was home to about seven percent of American Jews in 2018. That population, estimated at more than 470,000 year-round residents and an additional 56,000 seasonal residents, makes the tri-county area the third-largest Jewish center in the United States (after the census statistical areas of New York and Los Angeles) and the sixth-largest in the world. The area has far more Jews than any other metropolitan area in the historical South and at a much higher density; nearly eight percent of the total population lives in a Jewish household. Additionally, the overall ethnic and linguistic diversity of Miami and South Florida differentiate it from the rest of the South. For decades, in fact, popular conceptions of “the South” have often excluded South (and sometimes Central) Florida. Miami in particular appears more culturally tied to New York City and the Caribbean.

Despite South Florida’s reputation, however, its Jewish history mirrored that of other small and late developing communities in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. From tiny Jewish populations in 1900 to budding Jewish communities in the 1920s and 1930s, Jewish life there resembled much of the South. It was only after World War II that greater Miami came into its own as “the winter capital of American Jewry.” Since then, Jewish South Florida has diverged radically from other southern cities.

Despite South Florida’s reputation, however, its Jewish history mirrored that of other small and late developing communities in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. From tiny Jewish populations in 1900 to budding Jewish communities in the 1920s and 1930s, Jewish life there resembled much of the South. It was only after World War II that greater Miami came into its own as “the winter capital of American Jewry.” Since then, Jewish South Florida has diverged radically from other southern cities.

Late 19th Century

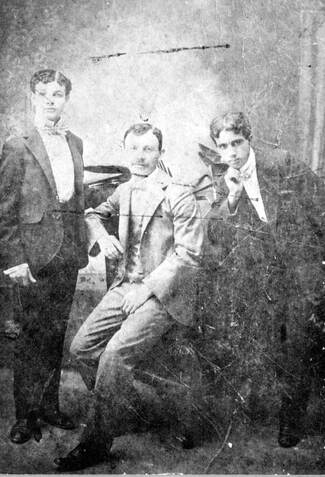

Three Jewish men, Miami, 1898. Isidore Cohen (center) is believed to be the first permanent Jewish resident of Miami. State Archives of Florida.

Three Jewish men, Miami, 1898. Isidore Cohen (center) is believed to be the first permanent Jewish resident of Miami. State Archives of Florida.

South Florida attracted few Euro-American settlers prior to 1900. As in much of the Florida Peninsula, a combination of climate, terrain, disease, and lack of infrastructure discouraged the growth of significant towns and cities. The earliest site of Jewish settlement in the area was likely West Palm Beach, where records show Jewish residences in 1892. These first arrivals came with the Florida East Coast Railway, which provided reliable transport to and from more established communities up the seaboard.

Jewish migrants gravitated to retail and operated stores in West Palm Beach near the landing for the ferry to Palm Beach. Some worked in local agriculture, including Max Serkin, who arrived in 1896 and owned a produce farm.

The new city of Miami also began to draw Jews, with a few transient merchants arriving in 1895. There were more than twenty Jews in Miami within a few years, and the fledgling community held religious services in members’ homes. A major fire in 1896 and a yellow fever outbreak in 1899 led many residents to leave the city, however, and in 1900 the Jewish population dropped to just three people.

Jewish migrants gravitated to retail and operated stores in West Palm Beach near the landing for the ferry to Palm Beach. Some worked in local agriculture, including Max Serkin, who arrived in 1896 and owned a produce farm.

The new city of Miami also began to draw Jews, with a few transient merchants arriving in 1895. There were more than twenty Jews in Miami within a few years, and the fledgling community held religious services in members’ homes. A major fire in 1896 and a yellow fever outbreak in 1899 led many residents to leave the city, however, and in 1900 the Jewish population dropped to just three people.

1900-1910s

The South Florida Jewish population grew only slightly in the next decade. The 1910 census shows five Jewish families in Miami. Others were scattered among the small communities in the area, including a handful of Jews in Homestead, thirty-some miles southwest of Miami, where there was also a short-lived cooperative Zionist chicken farm.

Joe and Jenny Weiss in front of Joe’s Restaurant, 1913. State Archives of Florida.

Joe and Jenny Weiss in front of Joe’s Restaurant, 1913. State Archives of Florida.

The 1910s saw the beginnings of Jewish organizational life in the area. In 1913, thirty-five Miami Jews met at the home of Mendel Rippa and established a Jewish section of the city cemetery, as well as the first South Florida congregation, B’nai Zion (now known as Beth David). Within a few years the Miami Jewish population numbered more than fifty people.

As Miami Jews began to found their first institutions, Jews also settled across Biscayne Bay in Miami Beach, which was emerging as a popular tourist destination. Joe and Jenny Weiss moved to the southern end of Miami Beach to run a “snack bar” in 1913. A few years later they opened Joe’s Stone Crab Shack in the same area—a business that the family still operated as of 2018. The Weiss’s location in south Miami Beach was dictated by anti-Semitic practices that excluded Jews as tourists, property owners, and tenants in most neighborhoods north of Fifth Street. These restrictions, encoded in overt and covert hotel policies and in restrictive covenants, remained in effect into the mid-1920s.

As Miami Jews began to found their first institutions, Jews also settled across Biscayne Bay in Miami Beach, which was emerging as a popular tourist destination. Joe and Jenny Weiss moved to the southern end of Miami Beach to run a “snack bar” in 1913. A few years later they opened Joe’s Stone Crab Shack in the same area—a business that the family still operated as of 2018. The Weiss’s location in south Miami Beach was dictated by anti-Semitic practices that excluded Jews as tourists, property owners, and tenants in most neighborhoods north of Fifth Street. These restrictions, encoded in overt and covert hotel policies and in restrictive covenants, remained in effect into the mid-1920s.

Boom Years

The real estate boom that fueled Florida’s economy in the early 1920s led to significant Jewish growth in South Florida. Temple Beth Israel (Reform, now Temple Israel) and Temple Beth El (Conservative) started in West Palm Beach in the early 1920s. They were the first Jewish congregations in Palm Beach County. In Broward County, Fort Lauderdale’s Jewish population became large enough to hold High Holiday services in 1926.

Beth David synagogue, 1924. State Archives of Florida

Beth David synagogue, 1924. State Archives of Florida

The most dramatic changes came in Miami and Miami Beach, however, which began to develop dense Jewish enclaves. Miami’s general population mushroomed from 30,000 to 130,000 people in the first half of the 1920s. By 1925, Miami was home to 3,500 Jews—more than sixty-times the figure from 1915. Miami Jews founded a variety of new organizations during this population explosion, including the city’s first Reform congregation, Temple Israel, in 1922.

In Miami Beach, the boom brought Jewish hoteliers and apartment owners to the neighborhood south of Fifth Street. Sam Magid, Joseph Goodowsky, and Harry Goodowsky opened Miami Beach’s first kosher hotel in 1921. Rose Weiss and her family arrived from New York City in 1919. They lived in and operated a fifteen-unit apartment building. Weiss developed a reputation for her empathy and civic involvement over the subsequent decades, earning the nickname “the Mother of Miami Beach.”

North of Miami Beach, Henri Levy spearheaded the fashionable developments of Normandy Isle and Normandy Beach North during the early 1920s boom years. The collapse of the Florida real estate market in 1925 provided opportunities for other Jewish developers, including Samuel Horvitz, who acquired extensive property in Hollywood (Broward County) from a bankrupt real estate company. By the end of the 1930s, Horvitz’s Hollywood Inc. served as a leading residential real estate broker in Hollywood. Jewish developers continued to ride the booms and busts of the South Florida economy for decades to come.

In Miami Beach, the boom brought Jewish hoteliers and apartment owners to the neighborhood south of Fifth Street. Sam Magid, Joseph Goodowsky, and Harry Goodowsky opened Miami Beach’s first kosher hotel in 1921. Rose Weiss and her family arrived from New York City in 1919. They lived in and operated a fifteen-unit apartment building. Weiss developed a reputation for her empathy and civic involvement over the subsequent decades, earning the nickname “the Mother of Miami Beach.”

North of Miami Beach, Henri Levy spearheaded the fashionable developments of Normandy Isle and Normandy Beach North during the early 1920s boom years. The collapse of the Florida real estate market in 1925 provided opportunities for other Jewish developers, including Samuel Horvitz, who acquired extensive property in Hollywood (Broward County) from a bankrupt real estate company. By the end of the 1930s, Horvitz’s Hollywood Inc. served as a leading residential real estate broker in Hollywood. Jewish developers continued to ride the booms and busts of the South Florida economy for decades to come.

Financial Crises and the Depression Era

The Great Depression came early to Florida. A devastating 1926 hurricane, which arrived on Yom Kippur, caused extensive damage across South Florida. The hurricane compounded the effects of the 1925 slowdown, and several local banks failed. A second hurricane hit the area in 1928, followed by the national stock market crash in 1929.

By the mid-1930s, South Florida had begun a slow recovery. Fort Lauderdale’s Jews organized Temple Emanu-El in 1931 and acquired their own building in 1937. The area’s overall population had decreased since the mid-1920s, but the Jewish population had grown, with an estimated 4,500 Jews living in Miami. The economic troubles reduced anti-Semitic restrictions, as many developers and businesses could no longer afford to be choosy about their clientele. The Miami Beach Jewish community grew to several thousand, and the Jewish population continued to spread northward into neighborhoods that had excluded them a decade or two earlier. Boca Raton—which attracted a more elite, old-money clientele than Miami Beach—saw its first Jewish businesses open in the 1930s. Harry and Florence Brown arrived in 1931, with Harry’s sister and brother-in-law, Nettie and Max Hutkin, following five years later.

As the 1930s progressed, Dade County not only continued its role as the dominant Jewish center in South Florida, but also emerged as the largest Jewish community in the state. Miami’s Jewish population surged ahead of Jacksonville’s, which had been the largest in the Florida for several decades. Miami Beach added another thousand or so Jews to the county’s total. In Miami proper, the Jewish community developed in the Shenandoah neighborhood, a few miles southwest of downtown.

By the mid-1930s, South Florida had begun a slow recovery. Fort Lauderdale’s Jews organized Temple Emanu-El in 1931 and acquired their own building in 1937. The area’s overall population had decreased since the mid-1920s, but the Jewish population had grown, with an estimated 4,500 Jews living in Miami. The economic troubles reduced anti-Semitic restrictions, as many developers and businesses could no longer afford to be choosy about their clientele. The Miami Beach Jewish community grew to several thousand, and the Jewish population continued to spread northward into neighborhoods that had excluded them a decade or two earlier. Boca Raton—which attracted a more elite, old-money clientele than Miami Beach—saw its first Jewish businesses open in the 1930s. Harry and Florence Brown arrived in 1931, with Harry’s sister and brother-in-law, Nettie and Max Hutkin, following five years later.

As the 1930s progressed, Dade County not only continued its role as the dominant Jewish center in South Florida, but also emerged as the largest Jewish community in the state. Miami’s Jewish population surged ahead of Jacksonville’s, which had been the largest in the Florida for several decades. Miami Beach added another thousand or so Jews to the county’s total. In Miami proper, the Jewish community developed in the Shenandoah neighborhood, a few miles southwest of downtown.

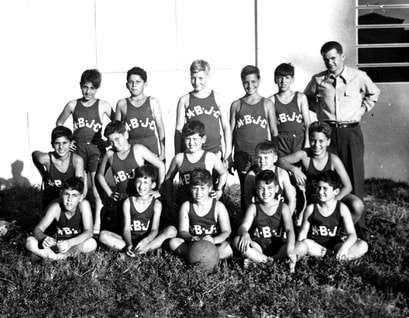

Miami Beach JCC Youth Basketball Team, early 1940s. State Archives of Florida.

Miami Beach JCC Youth Basketball Team, early 1940s. State Archives of Florida.

By the end of the 1930s, Miami area Jews had established a full range of Jewish institutions, primarily in Shenandoah and South Beach. In addition to various synagogues, they participated in B’nai B’rith, Hadassah, and the Young Men’s Hebrew Association. A local Workmen’s Circle branch offered Yiddish cultural programs and supported socialist and labor politics, and a Communist-oriented splinter group operated a branch of the International Worker’s Order (later the Jewish People’s Fraternal Order). A number of Zionist organizations were founded in Miami Beach during the 1940s. Jewish children attended congregational religious schools, and political organizations offered secular Jewish classes for youth. Beginning in 1927, area Jews kept up with organizational and social life through The Jewish Floridian, published weekly by editor J. Louis Schochet. They could also take advantage of the Jewish Welfare Bureau, founded in 1920, and contribute to the Greater Miami Jewish Federation, founded in 1938.

As South Beach attracted new Jewish residents it also developed its signature look. Jewish architect Henry Hohauser moved from New York in the 1930s and designed over one hundred Miami Beach buildings, many in the Streamline Moderne and Nautical Moderne styles that came to define South Beach. Decades later, in the 1970s and 1980s, Jewish residents Barbara Capitman and Leonard Horowitz led the push to preserve South Beach’s architectural legacy.

As South Beach attracted new Jewish residents it also developed its signature look. Jewish architect Henry Hohauser moved from New York in the 1930s and designed over one hundred Miami Beach buildings, many in the Streamline Moderne and Nautical Moderne styles that came to define South Beach. Decades later, in the 1970s and 1980s, Jewish residents Barbara Capitman and Leonard Horowitz led the push to preserve South Beach’s architectural legacy.

World War II and the Postwar Era in Miami and Miami Beach

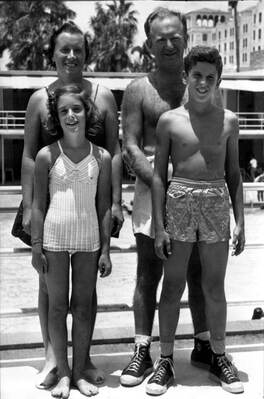

Ruth and Harry Rich, with children Lois and David, 1950. The family moved to Hollywood in 1949. State Archives of Florida.

Ruth and Harry Rich, with children Lois and David, 1950. The family moved to Hollywood in 1949. State Archives of Florida.

Miami’s Jewish community transformed dramatically between 1920 and 1940, but the growth that followed over the next twenty years turned South Florida into a key center of American Jewish life. In 1940, 9,000 individuals lived in Jewish households in South Florida. In 1950 that figure stood at 52,000, and it reached 134,000 by 1960.

The first factor in South Florida’s accelerated development was World War II. Florida’s business and government leaders successfully lobbied for military bases and training facilities across the state, and many of South Florida’s hotels served as temporary barracks. Federally funded infrastructure projects supported the new military operations, and servicemembers and their visiting families provided an influx of new consumers that compensated for the disruption to the tourism economy. Most significantly, perhaps, the war exposed tens of thousands of servicemembers to South Florida’s tropical climate, and many veterans returned to the area in the postwar years.

Jewish military personnel contributed to the growth of Jewish South Florida both during the war and after, as returning veterans. Miami Beach hosted a particularly large contingent of servicemembers, leading to the establishment of Beth Shalom Center (later Temple Beth Sholom) in 1942. The storefront congregation served military and civilian residents and was the first Reform synagogue in Miami Beach. Between 1930 and the end of World War II, South Florida Jews founded ten new congregations.

A second factor in South Florida’s general and Jewish growth was the development of technologies that made the area more comfortable for human inhabitants. During 1940s and 1950s the use of DDT and other insecticides reduced the mosquito population, and the widespread availability of air conditioning made the subtropical heat more manageable. Cheaper commercial air travel and the continued expansion of area airports made South Florida more accessible to seasonal residents and more appealing to potential migrants whose extended families still lived in the Northeast.

The majority of new Jewish arrivals settled in Dade County, where the Jewish population jumped by 40,000 residents (to 47,000) in the 1940s and another 72,000 over the next decade. During the first half of the 1950s, an estimated 650 Jews relocated to Dade County each month. Newcomers included families as well as retirees, and most came from the Northeast and Midwest. The established Jewish neighborhoods in Miami and Miami Beach continued to spread as new Jewish organizations sprung up to accommodate the growing community. By 1960, new congregations in North Miami, South Miami, and Coral Gables reflected Miami Jews’ increasing numbers in the city’s suburbs. Postwar growth also led to greater diversity of Jewish culture and practice in the area, evinced by the 1951 establishment of the Sephardic Jewish Center of Greater Miami, which served as both a synagogue and community center.

Along with religious, political, and cultural institutions, Miami-area Jews founded Mount Sinai Hospital (now Mount Sinai Medical Center) on Miami Beach in 1949, after local hospitals denied admitting privileges to Jewish doctors. Jews also gained recognition among the general population, demonstrated in part by Miami Beach city council member Mitchell Wolfson, who won election as mayor in 1943. Among other accomplishments, Wolfson and his brother-in-law, Sidney Meyer, founded WTVJ, Florida’s first television station. In 1953, Abe Arnowitz became the first Jewish mayor of Miami, a further signal of Jews’ rising prominence in Dade County. On the less legitimate side, Jews also helped to develop an illegal gambling industry in South Florida, with Meyer Lansky and the S&G Syndicate both offering gambling operations in the Miami area.

The first factor in South Florida’s accelerated development was World War II. Florida’s business and government leaders successfully lobbied for military bases and training facilities across the state, and many of South Florida’s hotels served as temporary barracks. Federally funded infrastructure projects supported the new military operations, and servicemembers and their visiting families provided an influx of new consumers that compensated for the disruption to the tourism economy. Most significantly, perhaps, the war exposed tens of thousands of servicemembers to South Florida’s tropical climate, and many veterans returned to the area in the postwar years.

Jewish military personnel contributed to the growth of Jewish South Florida both during the war and after, as returning veterans. Miami Beach hosted a particularly large contingent of servicemembers, leading to the establishment of Beth Shalom Center (later Temple Beth Sholom) in 1942. The storefront congregation served military and civilian residents and was the first Reform synagogue in Miami Beach. Between 1930 and the end of World War II, South Florida Jews founded ten new congregations.

A second factor in South Florida’s general and Jewish growth was the development of technologies that made the area more comfortable for human inhabitants. During 1940s and 1950s the use of DDT and other insecticides reduced the mosquito population, and the widespread availability of air conditioning made the subtropical heat more manageable. Cheaper commercial air travel and the continued expansion of area airports made South Florida more accessible to seasonal residents and more appealing to potential migrants whose extended families still lived in the Northeast.

The majority of new Jewish arrivals settled in Dade County, where the Jewish population jumped by 40,000 residents (to 47,000) in the 1940s and another 72,000 over the next decade. During the first half of the 1950s, an estimated 650 Jews relocated to Dade County each month. Newcomers included families as well as retirees, and most came from the Northeast and Midwest. The established Jewish neighborhoods in Miami and Miami Beach continued to spread as new Jewish organizations sprung up to accommodate the growing community. By 1960, new congregations in North Miami, South Miami, and Coral Gables reflected Miami Jews’ increasing numbers in the city’s suburbs. Postwar growth also led to greater diversity of Jewish culture and practice in the area, evinced by the 1951 establishment of the Sephardic Jewish Center of Greater Miami, which served as both a synagogue and community center.

Along with religious, political, and cultural institutions, Miami-area Jews founded Mount Sinai Hospital (now Mount Sinai Medical Center) on Miami Beach in 1949, after local hospitals denied admitting privileges to Jewish doctors. Jews also gained recognition among the general population, demonstrated in part by Miami Beach city council member Mitchell Wolfson, who won election as mayor in 1943. Among other accomplishments, Wolfson and his brother-in-law, Sidney Meyer, founded WTVJ, Florida’s first television station. In 1953, Abe Arnowitz became the first Jewish mayor of Miami, a further signal of Jews’ rising prominence in Dade County. On the less legitimate side, Jews also helped to develop an illegal gambling industry in South Florida, with Meyer Lansky and the S&G Syndicate both offering gambling operations in the Miami area.

Mid-Century Politics in Greater Miami

As Jews became more numerous, more prosperous, and more visible in Dade County, they faced a series of social and political issues related to Jews’ place as United States citizens and as a global ethnic and religious community. From 1940 to 1960, area Jews joined the growing Zionist movement in America, battled anti-Jewish exclusionary practices locally and across the state, struggled to respond collectively to the desegregation crisis, and challenged the dominance of Christian religious traditions in public schools.

The 1940s saw a rising interest in Zionism in South Florida, especially among the Jews of Miami Beach. Both the Zionist Organization of America (ZOA) and Jewish National Workers’ Alliance (a labor-Zionist fraternal order known commonly as the Farband) established local operations early in the decade. Shepard Broad, a central figure in the ZOA, helped organize support for the Haganah, in part by acquiring and equipping two ships used to transport Jewish migrants to Palestine in defiance of a blockade by the British Navy. By the late 1940s, nearly every Jewish organization in Miami Beach supported the idea of a Jewish state, and an estimated crowd of six thousand people joined a public celebration after the announcement of Israeli independence in May 1948. While some area Jews—especially members of Miami’s Classical Reform congregation, Temple Israel—disapproved of Israeli statehood, Zionism generally received a sympathetic response from South Florida’s white Christians.

Along with their increasing interest in Zionism, Miami area Jews led local and statewide efforts to combat exclusionary hotel policies. In Miami Beach, Jewish city council member Burnett Roth helped pass an ordinance to ban “Restricted Clientele” advertisements meant to ward off Jewish tenants and customers. When the ordinance was struck down in court, Dade County Jews lobbied for a state law that would permit local anti-discrimination rules. When the bill passed in 1949, Miami Beach adopted an ordinance against advertisements and signs that discriminated on the basis of religion or race. Jewish exclusion in tourism and housing decreased dramatically over the next decade. In 1953, one-fifth of hotels and motels in Miami Beach and Surfside would not rent to Jews, compared to a rate of over fifty percent in the rest of Florida. By the end of the 1950s, the statewide rate had dropped below fifteen percent.

The 1940s saw a rising interest in Zionism in South Florida, especially among the Jews of Miami Beach. Both the Zionist Organization of America (ZOA) and Jewish National Workers’ Alliance (a labor-Zionist fraternal order known commonly as the Farband) established local operations early in the decade. Shepard Broad, a central figure in the ZOA, helped organize support for the Haganah, in part by acquiring and equipping two ships used to transport Jewish migrants to Palestine in defiance of a blockade by the British Navy. By the late 1940s, nearly every Jewish organization in Miami Beach supported the idea of a Jewish state, and an estimated crowd of six thousand people joined a public celebration after the announcement of Israeli independence in May 1948. While some area Jews—especially members of Miami’s Classical Reform congregation, Temple Israel—disapproved of Israeli statehood, Zionism generally received a sympathetic response from South Florida’s white Christians.

Along with their increasing interest in Zionism, Miami area Jews led local and statewide efforts to combat exclusionary hotel policies. In Miami Beach, Jewish city council member Burnett Roth helped pass an ordinance to ban “Restricted Clientele” advertisements meant to ward off Jewish tenants and customers. When the ordinance was struck down in court, Dade County Jews lobbied for a state law that would permit local anti-discrimination rules. When the bill passed in 1949, Miami Beach adopted an ordinance against advertisements and signs that discriminated on the basis of religion or race. Jewish exclusion in tourism and housing decreased dramatically over the next decade. In 1953, one-fifth of hotels and motels in Miami Beach and Surfside would not rent to Jews, compared to a rate of over fifty percent in the rest of Florida. By the end of the 1950s, the statewide rate had dropped below fifteen percent.

Shirley Zoloth (seated, far left) at a workshop for the Congress of Racial Equality, 1959. State Archives of Florida.

Shirley Zoloth (seated, far left) at a workshop for the Congress of Racial Equality, 1959. State Archives of Florida.

While South Florida Jews faced decreasing social and economic barriers in the postwar years, the Miami area and Florida in general were slow to abandon racial segregation. In some instances, local Jews took the lead in anti-segregationist activism. Matilda “Bobbi” Graff moved to Miami with her husband Emmanuel and their children in the late 1940s and quickly joined the local branch of the Civil Rights Congress. The Graffs belonged to the Communist Party, and the Civil Rights Congress was known as a communist-front organization. The group supported Henry Wallace’s 1948 Progressive Party campaign, promoted African American civil rights, and defended civil liberties. Many of the white members came from the area’s significant Jewish-left circles, which centered around Miami Beach’s Jewish Cultural Center, run by the Communist-oriented Jewish People’s Fraternal Order. Among the non-Communist left, Miami area Jews also played significant roles as proponents of desegregation. Shirley and Milton Zoloth, for example, moved to Miami in 1954 and soon joined a progressive and Jewish social circle. In 1958, Shirley Zoloth and other Jewish women helped found a chapter of the biracial Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) to support desegregation efforts in Dade County schools and public accommodations.

Beyond the actions of Jewish radical groups and individual Jewish citizens, mainstream Jewish leaders and institutions were somewhat slow to confront segregation and white supremacy. In a notable exception, Mount Sinai Hospital had committed to serving white and Black patients from the time of its opening in 1949, and the hospital appointed an African American doctor in 1952—a progressive move at the time. During the 1950s, South Florida Jewish institutions tended not to publicly support desegregation and Black civil rights, but local rabbis and Jewish groups became more vocal on the subject in the 1960s.

South Florida Jews’ muted support for Black civil rights in the 1950s is somewhat surprising, given that so many of them were transplants from the North and had not grown up with Jim Crow. To some extent, their acceptance of southern segregation reflected the ubiquity of anti-Black racism outside the region, but Florida’s strongly anti-Semitic and anti-communist environment also played a role. After keeping a low profile during the war years, the Ku Klux Klan returned to public activity in 1946 with newspaper ads and roadside signs that read, “the KKK welcomes you.” In June 1951, a dynamite explosion caused significant damage to the Tifereth Israel Northside Jewish center. Three more bombing attempts at local Jewish institutions followed in October and December of the same year, one of which resulted in an explosion and damage. The timing and method of the attacks linked the anti-Semitic violence to bombings of African American and Catholic sites, including a Christmas Day explosion that killed Florida NAACP leader Harry T. Moore and his wife, Harriette. (Another dynamite explosion occurred in 1958 at the school of Orthodox congregation Temple Beth El.) White nationalist and segregationist leaders often decried the rising tide of Black civil rights activism as part of a Communist conspiracy, and progressive Jews were vulnerable to these charges regardless of their actual politics. In Florida, a state investigation into alleged Communist activity almost exclusively subpoenaed Jews. The investigation created a chilling effect for Jewish leaders and organizations who might have done more to challenge segregation, led to the closure of the radical Jewish Cultural Center in Miami Beach, and compelled a number of Jewish activists—including the Graff family—to move away.

Despite their vulnerabilities as well as their concerns for the opinions of the white, Christian majority, Miami Jews did raise objections to the role of Christianity in public schools. In the mid-1950s they opposed proposals to teach bible study in the classroom, offer religious classes as after-school programs, and distribute Christian bibles to seventh graders. Beginning in 1959, several Jewish families joined or otherwise contributed to a prominent court case that challenged the place of overtly Christian practices in the schools. Chamberlain v. Dade County, as the case was known, prompted strong backlash from white Christians, which alarmed some Jewish leaders. By the early 1960s, and in spite of Jewish ambivalence about both causes, non-Jews in the Miami area associated Jewishness with support for desegregation and opposition to religion in schools.

Beyond the actions of Jewish radical groups and individual Jewish citizens, mainstream Jewish leaders and institutions were somewhat slow to confront segregation and white supremacy. In a notable exception, Mount Sinai Hospital had committed to serving white and Black patients from the time of its opening in 1949, and the hospital appointed an African American doctor in 1952—a progressive move at the time. During the 1950s, South Florida Jewish institutions tended not to publicly support desegregation and Black civil rights, but local rabbis and Jewish groups became more vocal on the subject in the 1960s.

South Florida Jews’ muted support for Black civil rights in the 1950s is somewhat surprising, given that so many of them were transplants from the North and had not grown up with Jim Crow. To some extent, their acceptance of southern segregation reflected the ubiquity of anti-Black racism outside the region, but Florida’s strongly anti-Semitic and anti-communist environment also played a role. After keeping a low profile during the war years, the Ku Klux Klan returned to public activity in 1946 with newspaper ads and roadside signs that read, “the KKK welcomes you.” In June 1951, a dynamite explosion caused significant damage to the Tifereth Israel Northside Jewish center. Three more bombing attempts at local Jewish institutions followed in October and December of the same year, one of which resulted in an explosion and damage. The timing and method of the attacks linked the anti-Semitic violence to bombings of African American and Catholic sites, including a Christmas Day explosion that killed Florida NAACP leader Harry T. Moore and his wife, Harriette. (Another dynamite explosion occurred in 1958 at the school of Orthodox congregation Temple Beth El.) White nationalist and segregationist leaders often decried the rising tide of Black civil rights activism as part of a Communist conspiracy, and progressive Jews were vulnerable to these charges regardless of their actual politics. In Florida, a state investigation into alleged Communist activity almost exclusively subpoenaed Jews. The investigation created a chilling effect for Jewish leaders and organizations who might have done more to challenge segregation, led to the closure of the radical Jewish Cultural Center in Miami Beach, and compelled a number of Jewish activists—including the Graff family—to move away.

Despite their vulnerabilities as well as their concerns for the opinions of the white, Christian majority, Miami Jews did raise objections to the role of Christianity in public schools. In the mid-1950s they opposed proposals to teach bible study in the classroom, offer religious classes as after-school programs, and distribute Christian bibles to seventh graders. Beginning in 1959, several Jewish families joined or otherwise contributed to a prominent court case that challenged the place of overtly Christian practices in the schools. Chamberlain v. Dade County, as the case was known, prompted strong backlash from white Christians, which alarmed some Jewish leaders. By the early 1960s, and in spite of Jewish ambivalence about both causes, non-Jews in the Miami area associated Jewishness with support for desegregation and opposition to religion in schools.

Broward and Palm Beach Counties, 1940-1960

Ralph Gross with custom portable chicken coop, c. 1940s. Ralph and his wife, Ruth, owned a Fort Lauderdale chicken farm from 1939 to 1956. State Archives of Florida.

Ralph Gross with custom portable chicken coop, c. 1940s. Ralph and his wife, Ruth, owned a Fort Lauderdale chicken farm from 1939 to 1956. State Archives of Florida.

Like Dade County, the Jewish communities of Broward and Palm Beach Counties grew in the postwar period, although not always at the same explosive pace. Broward’s Jewish population rose from 1,000 in 1940 to 2,000 in 1950 and then mushroomed to 10,000 in 1960. In Palm Beach County, the 1,000 Jewish residents of 1940 tripled by 1950 and then grew to 5,000 by 1960.

In Broward County, the Jews of Hollywood began to hold services around 1940, drawing from the city’s dozen-or-so Jewish households. As elsewhere in South Florida, Jewish veterans contributed to postwar growth as they returned to their former training sites with young families in tow. Marcia Zerivitz writes that Jews have been involved in a variety of industries in Broward County: “retail and wholesale, real estate and development, military and science, education and health, law and medicine, citrus, cattle and poultry, insurance and banking, the arts and government.”

Congregational life in Broward expanded with the formation of the Jewish Community Center of Hollywood in 1942, and the center secured an empty retail space for their activities the next year. They hired their first rabbi, Max Kaufman, in 1946. In the 1950s the community center became Temple Sinai and affiliated with the Conservative movement. Around the same time, Hollywood’s Temple Beth El formed as an offshoot of Temple Emanu-El in Fort Lauderdale. Beginning in 1956, the former Hillcrest Country Club (donated by hotel owner Ben Tobin) served as the Reform congregation’s first synagogue.

The Jewish community in Palm Beach County grew significantly during these decades, although slower than in Broward. In 1947, the Lake Worth Hebrew Association gained its charter, becoming the newest of the county’s Jewish organizations. It later developed into Temple Beth Sholom of Lake Worth. The city of Palm Beach was not home to a synagogue until the early 1960s.

In Broward County, the Jews of Hollywood began to hold services around 1940, drawing from the city’s dozen-or-so Jewish households. As elsewhere in South Florida, Jewish veterans contributed to postwar growth as they returned to their former training sites with young families in tow. Marcia Zerivitz writes that Jews have been involved in a variety of industries in Broward County: “retail and wholesale, real estate and development, military and science, education and health, law and medicine, citrus, cattle and poultry, insurance and banking, the arts and government.”

Congregational life in Broward expanded with the formation of the Jewish Community Center of Hollywood in 1942, and the center secured an empty retail space for their activities the next year. They hired their first rabbi, Max Kaufman, in 1946. In the 1950s the community center became Temple Sinai and affiliated with the Conservative movement. Around the same time, Hollywood’s Temple Beth El formed as an offshoot of Temple Emanu-El in Fort Lauderdale. Beginning in 1956, the former Hillcrest Country Club (donated by hotel owner Ben Tobin) served as the Reform congregation’s first synagogue.

The Jewish community in Palm Beach County grew significantly during these decades, although slower than in Broward. In 1947, the Lake Worth Hebrew Association gained its charter, becoming the newest of the county’s Jewish organizations. It later developed into Temple Beth Sholom of Lake Worth. The city of Palm Beach was not home to a synagogue until the early 1960s.

1960s and 1970s

The postwar Jewish population surge in greater Miami had resulted in large part to a high number of retirees, and this trend accelerated in the 1960s. A generation of older Jews found themselves with steady sources of income from union pensions and social security benefits at an age when they could still live independently. At the same time, the suburbanization of younger American Jews and new African American migrations into heavily Jewish neighborhoods motivated older, longtime, Jewish residents to seek new homes. Miami Beach offered an affordable, urban environment that appealed to seasonal visitors and, increasingly, year-round residents. Jewish hotel owners refashioned their facilities into retirement apartments, and the median age Miami Beach Jews jumped from 43 in 1950 to 54 in 1960. American Jews began to morbidly refer to Miami Beach as “God’s waiting room.”

On the other side of Biscayne Bay, Jewish Miami shifted from the old, central neighborhoods of Shenandoah and Westchester to new suburbs in the south and north. By 1970 Miami’s original Jewish enclaves had nearly vanished, and those same areas were populated in large part by Cuban migrants.

On the other side of Biscayne Bay, Jewish Miami shifted from the old, central neighborhoods of Shenandoah and Westchester to new suburbs in the south and north. By 1970 Miami’s original Jewish enclaves had nearly vanished, and those same areas were populated in large part by Cuban migrants.

Rabbi Leon Kronish (standing, far left) at an Israel Bonds dinner, 1959. Eleanor Roosevelt is seated center. State Archives of Florida.

Rabbi Leon Kronish (standing, far left) at an Israel Bonds dinner, 1959. Eleanor Roosevelt is seated center. State Archives of Florida.

Greater Miami continued its rise as a national, then international, Jewish center. Miami Beach alone was home to at least 75 Jewish organizations in 1955, and the city hosted the annual conference of the Central Conference of American Rabbis in 1957. Miami and Miami Beach rabbis became nationally prominent as well. Three clergy in particular came to represent Miami in the postwar decades: Irving Lehrman at Conservative Temple Emanu-El (formerly Miami Beach Jewish Center); Leon Kronish at the liberal/Reform Temple Beth Sholom in Miami Beach; and Joseph Narot at the more established, classical Reform Temple Israel in Miami. All three oversaw membership increases, building projects, and expanded programming during periods of incredible Jewish growth in the area. Historian Deborah Dash Moore points out that each rabbi possessed the ambition and sense of showmanship necessary to draw in Jewish newcomers not yet affiliated with a local Jewish congregation.

In the early 1960s, Miami was unique among American Jewish centers for its combination of rapid postwar growth, large numbers of retired and seasonal residents, and a large Cuban-Jewish presence. Within two years of the 1959 ouster of Fulgencio Batista more than 3,000 Cuban Jews settled in the Miami area, a significant portion of the 70-percent of Cuban Jews who emigrated by 1961. The Jewish migrants tended to settle in Miami Beach—closer to other Jews than to fellow Cuban exiles—but, for the most part, they received a cool welcome from established Jews. In a short time, they began to establish their own congregations and organizations, including the Círculo Cubano-Hebreo (1961) and the Cuban Sephardic Hebrew Congregation (1968).

In Broward and Palm Beach Counties, the 1960s and 1970s saw the development of new retirement communities and an influx of older Jewish residents. Broward County’s Jewish population nearly quadrupled in the 1960s, reaching an estimated 39,000 individuals, and then exploded over the course of the next decade, when it boasted the fastest growing Jewish population in the United States. By 1980, the county was home to 174,000 Jews—over one-third of South Florida’s total. The new Jewish arrivals settled all over Broward County, although Jewish growth trailed in the southeastern cities of Hollywood and Hollandale.

Through 1970, Palm Beach County’s Jewish communities did not grow as quickly as those in Dade and Broward, but it soon experienced its own Jewish retirement boom. From 1970 to 1980 the Jewish population of South Palm Beach (Boca Raton and Delray Beach) jumped from 1,000 to 37,000. West Palm Beach, stretching from Boynton Beach to Jupiter, added 44,000 Jews in the same period.

The preference for Broward and Palm Beach Counties among a new generation of retirees reflected several trends. Like other urban centers across the United States, white flight and disinvestment from Miami contributed to an image of the city as crime ridden and rife with racial conflict. Second, the northern counties offered “low-rise” condominium communities that appealed to a wealthier generation of retirees who relocated from suburban neighborhoods. Third, even as the new developments catered to more affluent customers, the cost of living remained lower than in the urban setting of Miami Beach. In some cases, large numbers of retirees from a single neighborhood in the North took up residence in the same retirement community in South Florida. Historically, the high population of older Jews in South Florida has resulted in low rates of synagogue affiliation in comparison to other U.S. cities, as many Jews join congregations in order to enroll children in religious school.

In the early 1960s, Miami was unique among American Jewish centers for its combination of rapid postwar growth, large numbers of retired and seasonal residents, and a large Cuban-Jewish presence. Within two years of the 1959 ouster of Fulgencio Batista more than 3,000 Cuban Jews settled in the Miami area, a significant portion of the 70-percent of Cuban Jews who emigrated by 1961. The Jewish migrants tended to settle in Miami Beach—closer to other Jews than to fellow Cuban exiles—but, for the most part, they received a cool welcome from established Jews. In a short time, they began to establish their own congregations and organizations, including the Círculo Cubano-Hebreo (1961) and the Cuban Sephardic Hebrew Congregation (1968).

In Broward and Palm Beach Counties, the 1960s and 1970s saw the development of new retirement communities and an influx of older Jewish residents. Broward County’s Jewish population nearly quadrupled in the 1960s, reaching an estimated 39,000 individuals, and then exploded over the course of the next decade, when it boasted the fastest growing Jewish population in the United States. By 1980, the county was home to 174,000 Jews—over one-third of South Florida’s total. The new Jewish arrivals settled all over Broward County, although Jewish growth trailed in the southeastern cities of Hollywood and Hollandale.

Through 1970, Palm Beach County’s Jewish communities did not grow as quickly as those in Dade and Broward, but it soon experienced its own Jewish retirement boom. From 1970 to 1980 the Jewish population of South Palm Beach (Boca Raton and Delray Beach) jumped from 1,000 to 37,000. West Palm Beach, stretching from Boynton Beach to Jupiter, added 44,000 Jews in the same period.

The preference for Broward and Palm Beach Counties among a new generation of retirees reflected several trends. Like other urban centers across the United States, white flight and disinvestment from Miami contributed to an image of the city as crime ridden and rife with racial conflict. Second, the northern counties offered “low-rise” condominium communities that appealed to a wealthier generation of retirees who relocated from suburban neighborhoods. Third, even as the new developments catered to more affluent customers, the cost of living remained lower than in the urban setting of Miami Beach. In some cases, large numbers of retirees from a single neighborhood in the North took up residence in the same retirement community in South Florida. Historically, the high population of older Jews in South Florida has resulted in low rates of synagogue affiliation in comparison to other U.S. cities, as many Jews join congregations in order to enroll children in religious school.

Late 20th Century

While the Jewish populations of Broward and Palm Beach Counties continued to grow through the 1980s, Dade County peaked around 1980, with an estimated 230,000 Jews. By 1990, the county’s Jewish population had dropped below 170,000, due in large part to mortality rates among aging retirees, out-migration from Greater Miami, and the popularity of newer retirement communities in the other counties among migrants from out-of-state. These trends had a dramatic impact in Miami Beach, especially South Beach, where a colorful, working-class, and ethnically distinct milieu of older Jews had thrived since the 1960s. Although younger and more middle class Jews sometimes perceived South Beach as an anachronistic Jewish ghetto, older Jewish residents participated in a “rich Yiddish communal life underscored by a glorious tropical climate,” in the words of Joel Saxe. Cultural organizations from the full range of Jewish religious and political perspectives met daily into the 1980s, and public spaces such as Lummus Park served as outdoor venues for debate, story telling, speeches, and musical performances—largely in Yiddish.

This classic art deco building, designed by Henry Hohauser, was originally the site of Hoffman’s Cafeteria in the 1940s and later housed the famous gay nightclub Warsaw.

Photo by Phillip Pessar.

This classic art deco building, designed by Henry Hohauser, was originally the site of Hoffman’s Cafeteria in the 1940s and later housed the famous gay nightclub Warsaw.

Photo by Phillip Pessar.

As the retired Jewish population of Miami Beach dwindled, new residents took their place and the city’s image changed. In 1980, a new wave of Cuban immigrants arrived after the Mariel boatlift. Later in the decade, South Beach began to gentrify, and demand rose for its historic art deco buildings. In addition, Miami and Miami Beach developed a large gay and lesbian scene, with South Beach in particular known for vibrant nightlife. In Miami, a group of gay and lesbian Jews established the Metropolitan Community Synagogue, now known as Congregation Etz Chaim, in 1974. Etz Chaim was among the first congregations in the United States founded by and for lesbian and gay Jews, and Jewish Miamians participated in early meetings that led to the formation of international Jewish LGBTQ networks. Since 1995, Etz Chaim has occupied several locations in Broward County, where Fort Lauderdale and, more recently, Wilton Manors have long attracted LGBTQ vacationers and year-round residents.

In 1990 Broward County claimed 44 percent of South Florida Jews, with Dade and Palm Beach Counties almost evenly splitting the remainder. Palm Beach County’s retirement boom continued through the end of the century, however, while Dade County’s Jewish population continued its decline. With the fastest growing Jewish population in the United States during the 1990s, Palm Beach County began to rival Broward County, which actually saw a small decline during the same period. In 2000, twenty percent of Palm Beach County households were Jewish, the highest concentration of the three South-Florida counties.

In 1990 Broward County claimed 44 percent of South Florida Jews, with Dade and Palm Beach Counties almost evenly splitting the remainder. Palm Beach County’s retirement boom continued through the end of the century, however, while Dade County’s Jewish population continued its decline. With the fastest growing Jewish population in the United States during the 1990s, Palm Beach County began to rival Broward County, which actually saw a small decline during the same period. In 2000, twenty percent of Palm Beach County households were Jewish, the highest concentration of the three South-Florida counties.

21st Century

South Florida remains a global Jewish hub as of 2019, although the first decades of the 21st century have ushered in new developments. In addition to earlier Jewish immigrants from Cuba, the area has attracted a significant population of Spanish speaking Jews from Central and South America, as well as Jews from Israel. As a consequence, the Jewish population of greater Miami, in particular, is the most diverse in the country, according to demographer Ira Sheskin. Miami-Dade County also began to reverse the decline in its Jewish population decline, with increasing numbers of both young adults and Orthodox Jews. Broward County, also home to a diverse Jewish community and a large Israeli population, experienced a net loss of over 90,000 Jewish residents between 1997 and 2016, largely due to mortality among elderly Jews. The Jewish population of Northwest Broward County continued to grow, however. The Jewish population of Palm Beach County, by comparison, grew slightly from 2005 to 2018, with a significant increase in the number of children and young families.

While the distribution of Jews across the three counties of South Florida may change according to the area’s ongoing development, the greater Jewish community still accounts for approximately 7 percent of the United States Jewish population, and South Florida will likely maintain its status as one of the world’s largest Jewish centers for the foreseeable future.

While the distribution of Jews across the three counties of South Florida may change according to the area’s ongoing development, the greater Jewish community still accounts for approximately 7 percent of the United States Jewish population, and South Florida will likely maintain its status as one of the world’s largest Jewish centers for the foreseeable future.

Selected Bibliography

The Jewish Floridian, The Florida Jewish Newspaper Project, University of Florida Digital Collections.

Deborah Dash Moore, To the Golden Cities: Pursuing the American Jewish Dream in Miami and L.A.,

(New York: The Free Press, 1994).

Andrea Greenbaum, ed., The Jews of South Florida, (Boston: Brandeis University Press, 2005).

Irving Lehrman, “The Jewish Community of Greater Miami, 1896-1955”, Conference on the Writing of

Regional History in the South, with Special Emphasis on Religious and Cultural Groups (1956).

Raymond Mohl, Matilda “Bobbi” Graff, and Shirley M. Zoloth, South of the South: Jewish Activists

and the Civil Rights Movement in Miami, 1945-1960 (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2004).

Ira Sheskin, various community studies, available at www.jewishdatabank.org.

The Boca Raton Jewish Oral History Project (YouTube Playlist), Boca Raton Historical Society.

The Jewish Floridian, The Florida Jewish Newspaper Project, University of Florida Digital Collections.

Deborah Dash Moore, To the Golden Cities: Pursuing the American Jewish Dream in Miami and L.A.,

(New York: The Free Press, 1994).

Andrea Greenbaum, ed., The Jews of South Florida, (Boston: Brandeis University Press, 2005).

Irving Lehrman, “The Jewish Community of Greater Miami, 1896-1955”, Conference on the Writing of

Regional History in the South, with Special Emphasis on Religious and Cultural Groups (1956).

Raymond Mohl, Matilda “Bobbi” Graff, and Shirley M. Zoloth, South of the South: Jewish Activists

and the Civil Rights Movement in Miami, 1945-1960 (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2004).

Ira Sheskin, various community studies, available at www.jewishdatabank.org.

The Boca Raton Jewish Oral History Project (YouTube Playlist), Boca Raton Historical Society.