Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Tallahassee, FL

Overview

The history of Tallahassee begins with the indigenous Apalachee, a successful agrarian people whose capitol city, Anhaica, was located within today’s city limits. Spanish colonizers arrived in 1538 and the area remained under Spanish control (for the most part) until Florida was ceded to the United States in 1821. The earliest documentation of a Jewish presence in Tallahassee dates back to 1837, though a substantial Jewish community did not exist in Tallahassee until after the Civil War. Because of its central geographic positioning in Florida’s panhandle and proximity to southern Georgia, Jews from surrounding communities have travelled to the capital city for religious services. Tallahassee is the Florida state capitol and home to Florida State University, thus the city has had a high turnover rate of Jews working in state government and higher education or attending university. Tallahassee has elected two Jewish mayors, Sam Wahnish in 1939 and Gene Berkowitz in 1968 and 1971. As of 2019, Tallahassee continues to support a vibrant Jewish community and remains a communal center for Jews in nearby towns of southern Georgia and the Florida panhandle.

Early History

Although a Jewish community did not develop in Tallahassee until after the Civil War, Jews operated businesses and lived in Tallahassee dating back to at least 1837. That year, Raphael Jacob Moses owned a store in the city, but shortly after moved away from Tallahassee to St. Joseph, Apalachicola, and later Columbus, Georgia. Approximately fifteen Jews lived and worked in Tallahassee by 1860. Of these fifteen, at least three worked as merchants, two as harness makers, and two as bookkeepers. Five years later, as the Civil War came to a close, Robert Williams and Helena Dzialynsky moved from Jasper, Florida, to Tallahassee and had five daughters. The family opened a store and bought three cotton plantations. Although the extent to which the Jews of Tallahassee practiced Judaism or the organization of any sort of congregation is unknown, the newspaper reported in 1871 that these early Jews closed their stores for two days for Rosh Hashanah, signaling traditional customs. Other signals of religious observance were apparent through the practices of the Williams family, as all five of the daughters married Jewish men, and Robert Williams—whom the Weekly Floridian referred to as “the ‘King of the Jews’ in Tallahassee”—donated a Torah for the small community.

Tallahassee native Ruby Pearl Diamond (1886-1982), was a granddaughter of Robert Williams. According to Claire B. Levenson, she “was, to the Jews of Tallahassee, a symbolic link to their beginnings.” State Archives of Florida.

Tallahassee native Ruby Pearl Diamond (1886-1982), was a granddaughter of Robert Williams. According to Claire B. Levenson, she “was, to the Jews of Tallahassee, a symbolic link to their beginnings.” State Archives of Florida.

The last decades of the 19th century brought new growth and structure to the Jewish community. In 1872, William Levy moved to Tallahassee, followed by Jackson and Dora Burkheim the next year. In 1875, the community consisted of nine families, and there were enough Jewish children for the Burkheims to begin the first Sunday school. A Purim Ball was organized in 1878 for the nine families and an additional nine single men, which was covered extensively by the local press. In fact, many Jewish customs enthralled local newspaper writers. In 1877, after the first Jewish marriage in the town, the paper wrote that “Our Israelitish friends have for some time been looking forward with interest to the marriage of one of their race, and the event occurred on Wednesday last.”

Although it is not clear when the group began to religiously organize, the Jewish community met for prayer and housed their Torah in the Masonic Temple in the closing years of the 19th century. In the 1890s, the community designated two lots for a Jewish burial section in the Old City Cemetery, and a Hebrew Benevolent Society formed in 1896 to maintain them.

Although it is not clear when the group began to religiously organize, the Jewish community met for prayer and housed their Torah in the Masonic Temple in the closing years of the 19th century. In the 1890s, the community designated two lots for a Jewish burial section in the Old City Cemetery, and a Hebrew Benevolent Society formed in 1896 to maintain them.

Early 20th Century

Sam and Jennie Mendelson, 1911. State Archives of Florida.

Sam and Jennie Mendelson, 1911. State Archives of Florida.

Jewish migration to Florida’s capital lulled following the turn of the century, and the number of Jews began to shrink over the next few decades. In large part, this occurred when Prohibition activists began to achieve some success in Tallahassee around 1900. The ban on alcohol deterred people from visiting and moving to Tallahassee and subsequently harmed Jewish stores and hotels. Many of the Jewish families were forced to moved away because of the decrease in workers and sales. The Jewish community was partially sustained, however, by merchants and farmers outside of the city who travelled in to Tallahassee for its Jewish life. Tobacco farmers like Alfred and Carrie Wahnish, who came to the region in the 1880s and shortly after opened a 3,600-acre tobacco plantation, as well as Jews in towns such as Quincy, Live Oak, Monticello and Perry, all contributed to religious life in the out-migration years of the early 20th century.

In 1912, a former peddler and Gainesville merchant named Sam Mendelson and his wife Jennie Gelberg were trying to decide on where to move next. The couple, deciding between Miami and Tallahassee, chose the latter because it was a bigger city. In the years to come, however, the vast majority of people chose otherwise, many moving to South Florida. For much of the early 20th century, Tallahassee’s economy remained stagnant. The Florida government often met to discuss large-scale investments in southern cities like Tampa and Miami, where railroads herded droves of people who were investing in the open housing market. The Jewish community remained small and saw little growth before the 1930s, although Sam Mendelson went on to be a successful merchant in Tallahassee, owning many stores in the downtown district, including a furniture and a grocery store.

In 1912, a former peddler and Gainesville merchant named Sam Mendelson and his wife Jennie Gelberg were trying to decide on where to move next. The couple, deciding between Miami and Tallahassee, chose the latter because it was a bigger city. In the years to come, however, the vast majority of people chose otherwise, many moving to South Florida. For much of the early 20th century, Tallahassee’s economy remained stagnant. The Florida government often met to discuss large-scale investments in southern cities like Tampa and Miami, where railroads herded droves of people who were investing in the open housing market. The Jewish community remained small and saw little growth before the 1930s, although Sam Mendelson went on to be a successful merchant in Tallahassee, owning many stores in the downtown district, including a furniture and a grocery store.

Organized Jewish Life

Organized Jewish life began to pick back up in the late 1920s. In 1929, Blanche Goldsmith led a group of nine women in organizing a sisterhood. The group elected Goldsmith as their first president, who led the sisterhood in fundraising from surrounding towns and throwing bridge parties to aid the local community. Tuition money was given to Jewish women to enroll in the local Florida State College for Women, which opened in 1905 as the Florida Female College. The sisterhood also donated to the local milk fund, which served underprivileged children, and eventually began to contribute to orphan homes and charity hospitals. Goldsmith served as president until 1936 when she was replaced by Jennie Mendelson.

When a visitor came to Tallahassee in 1878, he noted that “the Israelites ae increasing in number and prosperity and that [before] long they expect to build a synagogue.” His predications, however, turned out to be wrong. The Jewish population had decreased in number, and it was 59 years before a synagogue was built. In the meantime, the Jewish community only met for high holidays in the Masonic lodge, and Harry Mendelson (brother of Sam) conducted services.

When a visitor came to Tallahassee in 1878, he noted that “the Israelites ae increasing in number and prosperity and that [before] long they expect to build a synagogue.” His predications, however, turned out to be wrong. The Jewish population had decreased in number, and it was 59 years before a synagogue was built. In the meantime, the Jewish community only met for high holidays in the Masonic lodge, and Harry Mendelson (brother of Sam) conducted services.

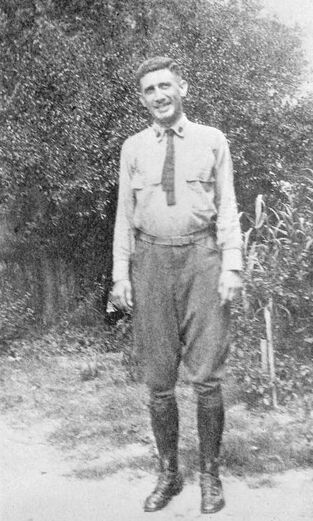

Sam Wahnish in military uniform, c. 1918. State Archives of Florida.

Sam Wahnish in military uniform, c. 1918. State Archives of Florida.

Finally, in 1937, under the leadership of Sam Mendelson, about 25 families met in the Mendelsons’ home to coordinate the opening of a synagogue, Temple Israel. They elected Mendelson as president, Al Block as vice president, H. H. Bluestein as secretary, and Sam Robbins as treasurer. Sarah Levy donated the land on which the temple was built in the memory of her husband William, one of the earliest Jews in Tallahassee; Mendelson inaugurated a fundraising effort for the building. The temple was built on Copeland street, and the community hired its first rabbi, David Max Eichorn, in 1939. Eichorn also led 100 Jewish students at FSCW. Around Florida, Jewish families contributed to his salary; the Gainesville community matched Tallahassee’s 1,800 dollars, and Hillel covered the rest. Meanwhile, B’nai B’rith opened Lodge 1043 in Tallahassee in 1938 and the community founded the first fully Jewish cemetery in 1942.

Outside of the religious sphere, Jewish businesspeople and politicians found success in the 1930s. In 1932, Sam and Fanny Rosenberg established Rose Printing, which grew to become one of the largest bookbinders and printing companies in the southeast United States. Additionally, because of the nature of being a Jewish community in a capital city, a certain transient Jewish community existed as well. When Jewish politicians served terms in Tallahassee, they often attended services at Temple Israel. David Sholtz, the Jewish governor from Daytona Beach inaugurated in 1933, joined the congregation during his term in office. In local office, Tallahassee’s voters elected Sam Wahnish—who served as president of the American Legion and Elks Club—as mayor in 1939, a position he held until 1941.

Outside of the religious sphere, Jewish businesspeople and politicians found success in the 1930s. In 1932, Sam and Fanny Rosenberg established Rose Printing, which grew to become one of the largest bookbinders and printing companies in the southeast United States. Additionally, because of the nature of being a Jewish community in a capital city, a certain transient Jewish community existed as well. When Jewish politicians served terms in Tallahassee, they often attended services at Temple Israel. David Sholtz, the Jewish governor from Daytona Beach inaugurated in 1933, joined the congregation during his term in office. In local office, Tallahassee’s voters elected Sam Wahnish—who served as president of the American Legion and Elks Club—as mayor in 1939, a position he held until 1941.

World War II and After

As in many cities around Florida, World War II ushered in major changes for Tallahassee and its Jewish community. Camp Gordon Johnson, located some 50 miles southwest of Tallahassee, housed upwards of 750 Jewish soldiers during the war, and Temple Israel became a welcoming congregation for them. The temple inaugurated the Temple Israel Canteen Service, offering necessities to the men and women serving at the camp. Members of the congregation spent evenings at the temple, hosting soldiers for dinner and events, and invited Jewish soldiers into their homes. Molly Horn, the president of the temple sisterhood, organized a Sukkot dinner for 100 soldiers, and then a Seder for 700. The temple also awarded phone calls to Jewish soldiers.

Tallahassee’s population grew considerably after the war, from 16,000 in 1940 to over 27,000 ten years later. A number of new small Jewish businesses opened during this time as well. In 1955, Temple Israel erected a Sunday school building on land donated by Al and Evelyn Block. (Sunday school was previously held in private homes or in the temple.) The Blocks were instrumental not just in Jewish education, but also in reforming general public education. Al was a founder of Florida’s Minimum Foundation Program, which guaranteed a basic level of education for every child in Florida and helped to develop a community college system in the state. The community engaged in work in the local prison as well. Correspondence between the Synagogue Council of America in New York and Rabbi Julius Kravetz shows that a handful of Jewish inmates were housed at the local prison and Rabbi Kravetz visited them multiple times per month.

By the end of the 1950s, fifty families made up Temple Israel, and the congregation continued to grow in the coming years.

By the end of the 1950s, fifty families made up Temple Israel, and the congregation continued to grow in the coming years.

Civil Rights and the 1960s-1970s.

From the early 1900s through the 1960s, Tallahassee had a reputation as being one of Florida’s most racist and segregated cities. Consequently, when the Civil Rights Movement began to gain support across the South, local citizens and traveling demonstrators chose the capital city as the location of various protests and sit-ins. Notably, the Tallahassee bus boycott lasted nearly seven months in 1956 after two black Florida A&M students refused to give up their seats and were charged with “inciting a riot.” Five years later, a New Jersey-based rabbi named Israel Dresner traveled to Tallahassee as part of a Freedom Ride with eight other clergymen. After a sit-in at an airport food counter, Dresner and the other eight protesters were arrested. Dresner, sometimes dubbed “the most arrested rabbi in America,” fought the airport arrest in a case that went all the way to the Supreme Court as Dresner et al. v. Tallahassee.

Laying of the cornerstone for new Temple Israel sanctuary, 1973. State Archives of Florida.

Laying of the cornerstone for new Temple Israel sanctuary, 1973. State Archives of Florida.

In the late 1960s, under new Rabbi Stanley Garfein, the congregational leadership realized the need to expand the temple to accommodate for its growing congregation. In 1970, 75 families made up Tallahassee’s only congregation, and the group was beginning to outgrow the 1939 sanctuary. They decided to construct an entirely new building at the location of the religious school. In 1973, the congregation laid the cornerstone was for a brand new, $300,000, 700-seat sanctuary on the Mahan street plot.

In May 1979, Rabbi Garfein told the Tallahassee Democrat, “I don’t think the pulpit should be silent on the questions of the day. There’s something to be said for ambiguity in prayer because more people can say ‘Amen.’ But there is also something to be said for being specific because how else can one express one’s convictions?” Garfein testified before the State Legislature advocating for marijuana legalization and the removal of antiquated sex laws. Garfein also opposed the death penalty, believed the drinking age should not be increased, and that contraceptive information should be made available to minors. Years earlier, Garfein criticized then-president Gerald Ford for pardoning Richard Nixon, which “disturbed” some of his congregation members. Despite some the controversy or discomfort Rabbi Garfein’s politics may have caused among congregants, it is telling that Temple Israel hired such a progressive-minded clergyperson who publicly advocated for social justice issues both from his pulpit and before the greater Tallahassee community.

In May 1979, Rabbi Garfein told the Tallahassee Democrat, “I don’t think the pulpit should be silent on the questions of the day. There’s something to be said for ambiguity in prayer because more people can say ‘Amen.’ But there is also something to be said for being specific because how else can one express one’s convictions?” Garfein testified before the State Legislature advocating for marijuana legalization and the removal of antiquated sex laws. Garfein also opposed the death penalty, believed the drinking age should not be increased, and that contraceptive information should be made available to minors. Years earlier, Garfein criticized then-president Gerald Ford for pardoning Richard Nixon, which “disturbed” some of his congregation members. Despite some the controversy or discomfort Rabbi Garfein’s politics may have caused among congregants, it is telling that Temple Israel hired such a progressive-minded clergyperson who publicly advocated for social justice issues both from his pulpit and before the greater Tallahassee community.

A New Congregation

Until the 1970s, Temple Israel stood as the singular house of Jewish worship in Tallahassee. As new families moved to the city, however, new forms of religious belief came with them. For some time, a “loose chavarah” existed, holding lay-led Shabbat services. In 1976, a group of six families—the Fishmans, Coopers, Norvelles, Shapiros, Kaufman, and Kaplans—decided to split off from Reform Temple Israel and begin their own conservative congregation. The group called themselves Shomrei Torah and held early services at the Church of the Advent on Piedmont street. Once they joined of United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism (USCJ), the new congregation began to recruit members from Temple Israel who they believed may be more interested in a Conservative congregation. After an early disagreement between the two congregations over the use of a Torah, Jay Kaufman loaned Shomrei Torah a family Torah, which they stored in the church basement. Other Conservative congregations donated siddurim and tallitot.

Shomrei Torah, 2018.

Shomrei Torah, 2018.

While Temple Israel and Shomrei Torah competed for membership, the congregations also collaborated and intermingled at times. Sheldon Gusky, who arrived in Tallahassee in 1967 to attend school and joined Shomrei Torah in the spring of 1983, formed a Cub Pack and Boy Scout Troop in 1993 that had equal membership from both congregations. Led by Andy Grayson, nearly twenty young boys and their fathers joined the group. Gusky recalled that organizing the Cub Pack and Boy Scout Troop “required a coordination of two entities.”

In the 1980s, newcomers were drawn to Tallahassee for state government jobs, to attend school, and to open new businesses, medical, and law practices. Tallahassee also remained a hub for Jews from smaller towns in northern Florida and southern Georgia who came to Tallahassee for Jewish communal events and holidays. Monte Finkelstein, the current President of Shomrei Torah as of 2019, recalled that Jews came to Tallahassee from southern Florida to “escape” Miami, as Tallahassee was “rustic” compared to “hectic” and “concreted” Miami.

Hillel arrived at Florida State University in the 1980s, drawing students who had previously sought community at Temple Israel or Shomrei Torah back to campus for holiday and Shabbat services. Florida State Association of B’nai B’rith Lodges, through its corporation Florida Hillel Foundations, Inc. built the FSU Hillel House next to campus of FSU in 1982. Chabad also began to organize at FSU by 2000. However, some college-aged Jews still remain engaged with Shomrei Torah, where they teach religious school .

In the 1980s, newcomers were drawn to Tallahassee for state government jobs, to attend school, and to open new businesses, medical, and law practices. Tallahassee also remained a hub for Jews from smaller towns in northern Florida and southern Georgia who came to Tallahassee for Jewish communal events and holidays. Monte Finkelstein, the current President of Shomrei Torah as of 2019, recalled that Jews came to Tallahassee from southern Florida to “escape” Miami, as Tallahassee was “rustic” compared to “hectic” and “concreted” Miami.

Hillel arrived at Florida State University in the 1980s, drawing students who had previously sought community at Temple Israel or Shomrei Torah back to campus for holiday and Shabbat services. Florida State Association of B’nai B’rith Lodges, through its corporation Florida Hillel Foundations, Inc. built the FSU Hillel House next to campus of FSU in 1982. Chabad also began to organize at FSU by 2000. However, some college-aged Jews still remain engaged with Shomrei Torah, where they teach religious school .

Conclusion

As of 2019, the Tallahassee Jewish community supports Temple Israel, Shomrei Israel, Chabad Lubavitch of the Pandhandles, as well as the FSU Hillel. In 2005, Tallahassee, a city of 181,000 people, was home to approximately 2,800 Jews—a figure which does not seem to include Jewish students at Florida State University. The Jewish Federation of Tallahassee hosts numerous cultural, religious, and philanthropic events such as The Teen Philanthropy Initiative, the Big Bend Social Club for seniors, and the Tallahassee Jewish Film Series. The Jewish community’s longer history is also visible in town, as a fairly busy road that runs along the east side of Florida A&M University is called “Wahnish Way,” after the early and influential Jewish family.