Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Fort Myers, FL

Like other parts of Florida’s southern Gulf Coast, Charlotte, Lee, and Collier Counties remained rural and largely undeveloped until the 20th century. Despite the Jewish origins of Fort Myers’ name, the three-county area did not support an organized Jewish community until the mid-20th century. Since then, the Jewish presence in the area has increased with continued growth and the influx of retirees. As of the early 21st century, each county supports Jewish organizations, from Port Charlotte in Charlotte County (in the north) to Naples and Marco Island in Collier County.

Early Jewish History

Although no Jewish community existed in the Charlotte, Lee, and Collier County area until well into the 20th century, one of Southwest Florida’s early Euro-American settlements was named after a southerner of Jewish descent. When Major General David E. Twiggs, based at the time in present-day Tampa, ordered the construction of a new fort on the Caloosahatchee River in 1850, he named it after Colonel Abraham C. Myers, his daughter’s suitor and eventual husband. Myers, born in South Carolina in 1811, was a descendant of Moses Cohen, the first Rabbi to serve in Charleston. At the time of the fort’s founding, Myers was the chief quartermaster of the Department of Florida. He later served in the Confederate army. While Abraham Myers never lived in Fort Myers and likely did not practice Judaism, his role as namesake of the city does reflect the long presence of Jews and Americans of Jewish descent in the South.

Fort Myers remained a remote destination for the remainder of the 19th century. Initially, the fort existed to exert military control over the nearby Seminole population, and Southwest Florida attracted few Anglo-American settlers in the decades after its founding. By the end of the century, Fort Myers developed into a winter destination for affluent northerners, including Thomas Edison. Henry Ford and Harvey Firestone also built homes there in the early 20th century. Along with wealthy industrialists, the area was home to the Koreshan Unity, a utopian religious community that settled south of Fort Myers in Estero. The Koreshan movement claimed to be compatible, to some degree, with Judaism, and census records suggest that the community included at least a handful of adherents from Jewish backgrounds. Outside the commune, Jews may have come to the Fort Myers in these years to run businesses, but no lasting Jewish population developed.

In Charlotte County, to the north, at least one Jewish family had made a home before 1900. Jacob Wotitzky immigrated to the United States from Central Europe and opened a store in what is now Punta Gorda in the 1880s. His son Edward joined the business around 1890, and the Wotitzky family became prominent in business and civic affairs. Edward Wotitzky’s 1941 obituary recalls that Jacob Wotitzky had operated the store in town while Edward delivered goods by schooner to customers “up and down the coast and among the adjacent islands.” Another Jewish merchant named Goldstein seems to have traded in the area at the same time, and Goldstein Street in Punta Gorda’s downtown carries his name. The Wotitzky family was actively Jewish, as evidenced by Edward’s 1908 marriage to Celia Hart, which was performed by Rabbi Stollnitz in Tampa. Their remote location isolated them from other Jews, however. Edward and Celia’s sons continued the family’s legacy of civic leadership, but it is not clear whether they actively identified as Jewish.

Fort Myers remained a remote destination for the remainder of the 19th century. Initially, the fort existed to exert military control over the nearby Seminole population, and Southwest Florida attracted few Anglo-American settlers in the decades after its founding. By the end of the century, Fort Myers developed into a winter destination for affluent northerners, including Thomas Edison. Henry Ford and Harvey Firestone also built homes there in the early 20th century. Along with wealthy industrialists, the area was home to the Koreshan Unity, a utopian religious community that settled south of Fort Myers in Estero. The Koreshan movement claimed to be compatible, to some degree, with Judaism, and census records suggest that the community included at least a handful of adherents from Jewish backgrounds. Outside the commune, Jews may have come to the Fort Myers in these years to run businesses, but no lasting Jewish population developed.

In Charlotte County, to the north, at least one Jewish family had made a home before 1900. Jacob Wotitzky immigrated to the United States from Central Europe and opened a store in what is now Punta Gorda in the 1880s. His son Edward joined the business around 1890, and the Wotitzky family became prominent in business and civic affairs. Edward Wotitzky’s 1941 obituary recalls that Jacob Wotitzky had operated the store in town while Edward delivered goods by schooner to customers “up and down the coast and among the adjacent islands.” Another Jewish merchant named Goldstein seems to have traded in the area at the same time, and Goldstein Street in Punta Gorda’s downtown carries his name. The Wotitzky family was actively Jewish, as evidenced by Edward’s 1908 marriage to Celia Hart, which was performed by Rabbi Stollnitz in Tampa. Their remote location isolated them from other Jews, however. Edward and Celia’s sons continued the family’s legacy of civic leadership, but it is not clear whether they actively identified as Jewish.

The Beginnings of Local Communities

Celia Tanner, c. 1920. State Archives of Florida.

Celia Tanner, c. 1920. State Archives of Florida.

The population of southwest Florida grew significantly in the early twentieth century, spurred in part by new infrastructure construction, as well as the statewide real estate boom of the 1920s. The seeds of a permanent Jewish community did not emerge until the 1930s, however. In 1936, Herman and Celia Tanner moved from Tampa to Fort Myers. He opened a scrap metal business that developed into an auto parts company by 1945. Sam and Rose Posner also arrived in Fort Myers in the 1940s and ran a downtown variety store. Jews were a rarity in Southwest Florida at the time. According to local histories, when Sam Posner took out an ad in 1947 announcing that his store would be closed for the High Holy Days, a flood of customers came to the store who were excited to meet a Jew, and “he had his best day ever.”

Adding to these new families, the United States’ entry into World War II brought new Jewish residents to the Fort Myers area and precipitated the beginnings of Jewish organizational life. A number of Jewish servicemen were stationed at nearby Buckingham Army Air Base, and a Jewish military chaplain served there during the war. By 1944, local Jews joined Jewish military personnel for Jewish holidays on the base. Following the war, local Jews continued to meet, renting a Moose Hall for five dollars in order to hold Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur services in 1948. Community members also hosted lay-led Friday evening services and religious school classes in their homes.

Adding to these new families, the United States’ entry into World War II brought new Jewish residents to the Fort Myers area and precipitated the beginnings of Jewish organizational life. A number of Jewish servicemen were stationed at nearby Buckingham Army Air Base, and a Jewish military chaplain served there during the war. By 1944, local Jews joined Jewish military personnel for Jewish holidays on the base. Following the war, local Jews continued to meet, renting a Moose Hall for five dollars in order to hold Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur services in 1948. Community members also hosted lay-led Friday evening services and religious school classes in their homes.

Torah procession at religious services, Buckingham Army Air Field, 1944. State Archives of Florida.

Torah procession at religious services, Buckingham Army Air Field, 1944. State Archives of Florida.

As Jews of Fort Myers began to organize, they drew families from outlying areas, including Punta Gorda and Naples. In 1954, a group of 14 local Jews met in the home of of Herman and Celia Tanner and voted to establish a Jewish organization, which incorporated as the Fort Myers Jewish Community Center. The group raised several thousand dollars within a few months and reached a membership of 30 families. Shortly after breaking ground on a synagogue in August 1955 they adopted the name Temple Beth El. The congregation moved into the new building the following year.

Development Booms

Temple Beth El emerged during a period of rapid growth in Lee County, due in part to a series of new residential developments in the Fort Myers area. The two largest of these, Lehigh Acres and Cape Coral, were both headed by Jewish businessmen.

The first developer, Lee Ratner, came from Chicago and had made a fortune as the founder of d-Con, originally a mail-order pest control company. In the early 1950s, he purchased an 18,000-acre ranch east of Fort Myers, which likely served as a tax shelter. In 1954, Ratner and his business associates began to sell off undeveloped lots from the ranch land on installment plans, drawing middle-class buyers from the North, especially the midwest, with dreams of cheap living and sunny weather for their future retirements. In the late 1950s, when buyers started moving down, the developers began to build canal and street infrastructure as well as homes.

Not long after the founding of Lehigh Acres, brothers Leonard and Jack Rosen began to develop Cape Coral to the west of Fort Myers, across the Caloosahatchee River. To do so, the Rosen brothers started the Gulf American Land Corporation (later shortened to Gulf American Corporation), which built an intricate grid of canals and roads out of a low lying peninsula of former timber land. Along with intensive earth moving operations, both Lehigh Acres and Cape Coral relied on aggressive marketing tactics to lure their customers. Each project began with an influx of cash from eager buyers, but ran into trouble down the road when the costs of actually developing the land began to mount. By mid-1960s, Lee Ratner and the Rosen brothers had encountered financial and legal challenges, and they sold off their development companies by the end of the decade.

Despite ethical missteps, logistical puzzles, and public controversy, Cape Coral and Lehigh Acres did attract new families to the area, and Lee County’s population boomed in the 1950s and 1960s. The newcomers included Jewish residents, a sizable number of whom worked for Gulf American Corporation. In 1965, the company proved instrumental in Temple Beth El’s move from Fort Myers to Cape Coral; Jack and Leonard Rosen contributed money as well as a plot of Cape Coral land for a new synagogue, and they encouraged their Jewish employees—who lived in Cape Coral—to join the congregation. Lee Ratner similarly donated the land for Temple Emmanuel in Lehigh Acres, which was dedicated in 1970. To the north of Fort Myers and Cape Coral, Jews also began to settle in Charlotte county. Port Charlotte Jews founded a Reform congregation, originally called Port Charlotte Jewish Center (now Temple Shalom), in the early 1960s, and a Conservative congregation (Temple Beth El) organized in North Port the following decade.

The first developer, Lee Ratner, came from Chicago and had made a fortune as the founder of d-Con, originally a mail-order pest control company. In the early 1950s, he purchased an 18,000-acre ranch east of Fort Myers, which likely served as a tax shelter. In 1954, Ratner and his business associates began to sell off undeveloped lots from the ranch land on installment plans, drawing middle-class buyers from the North, especially the midwest, with dreams of cheap living and sunny weather for their future retirements. In the late 1950s, when buyers started moving down, the developers began to build canal and street infrastructure as well as homes.

Not long after the founding of Lehigh Acres, brothers Leonard and Jack Rosen began to develop Cape Coral to the west of Fort Myers, across the Caloosahatchee River. To do so, the Rosen brothers started the Gulf American Land Corporation (later shortened to Gulf American Corporation), which built an intricate grid of canals and roads out of a low lying peninsula of former timber land. Along with intensive earth moving operations, both Lehigh Acres and Cape Coral relied on aggressive marketing tactics to lure their customers. Each project began with an influx of cash from eager buyers, but ran into trouble down the road when the costs of actually developing the land began to mount. By mid-1960s, Lee Ratner and the Rosen brothers had encountered financial and legal challenges, and they sold off their development companies by the end of the decade.

Despite ethical missteps, logistical puzzles, and public controversy, Cape Coral and Lehigh Acres did attract new families to the area, and Lee County’s population boomed in the 1950s and 1960s. The newcomers included Jewish residents, a sizable number of whom worked for Gulf American Corporation. In 1965, the company proved instrumental in Temple Beth El’s move from Fort Myers to Cape Coral; Jack and Leonard Rosen contributed money as well as a plot of Cape Coral land for a new synagogue, and they encouraged their Jewish employees—who lived in Cape Coral—to join the congregation. Lee Ratner similarly donated the land for Temple Emmanuel in Lehigh Acres, which was dedicated in 1970. To the north of Fort Myers and Cape Coral, Jews also began to settle in Charlotte county. Port Charlotte Jews founded a Reform congregation, originally called Port Charlotte Jewish Center (now Temple Shalom), in the early 1960s, and a Conservative congregation (Temple Beth El) organized in North Port the following decade.

New Congregations

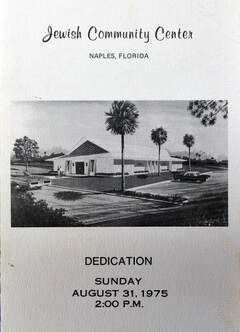

Program for the dedication of the Jewish Community Center of Naples, 1975. Jewish Museum of Florida.

Program for the dedication of the Jewish Community Center of Naples, 1975. Jewish Museum of Florida.

Naples, about 40 miles down the coast from Fort Myers, was still a small town of just a few thousand residents when Jewish families began to arrive in the 1950s. These early Jewish residents included the Freschel, Gilman, Dinaburg, and Luff families, and most of them moved to Naples to start businesses. When Gulf American Corporation established Golden Gate and Golden Gate Estates nearby, the new development projects brought in additional Jewish salesmen to the area. Soon there was a large enough Jewish community to host High Holiday services, and they founded the Jewish Community Center of Collier County in 1962.

In addition to Jewish workers and business owners involved in retail, real estate, and related industries, several Jewish families relocated to Southwest Florida to work in produce. Most notably, the Lipman family of Hollywood, Florida, opened a tomato farm near Naples in the 1950s. Within a few years, they operated more than 1,600 acres of farmland near Immokalee and soon moved the company headquarters there. Most family members continued to live on the east coast of Florida, but others, including Arby (Abraham) and Gloria Lipman, eventually moved to nearby Naples. The Lipmans, especially Arby’s brother Lou, were instrumental in the fundraising and construction for Jewish institutions, including the first independent building for the Jewish Community Center, dedicated in 1975.

By the 1970s, Naples had become a popular retirement destination—especially for Midwesterners—which led to growth in the Jewish population. The Jewish Community Center operated as a lay-led, Reform congregation until 1977, when they hired Abraham Shusterman. In 1980, the congregation added educational and social facilities to the building and changed its name to Temple Shalom.

In addition to Jewish workers and business owners involved in retail, real estate, and related industries, several Jewish families relocated to Southwest Florida to work in produce. Most notably, the Lipman family of Hollywood, Florida, opened a tomato farm near Naples in the 1950s. Within a few years, they operated more than 1,600 acres of farmland near Immokalee and soon moved the company headquarters there. Most family members continued to live on the east coast of Florida, but others, including Arby (Abraham) and Gloria Lipman, eventually moved to nearby Naples. The Lipmans, especially Arby’s brother Lou, were instrumental in the fundraising and construction for Jewish institutions, including the first independent building for the Jewish Community Center, dedicated in 1975.

By the 1970s, Naples had become a popular retirement destination—especially for Midwesterners—which led to growth in the Jewish population. The Jewish Community Center operated as a lay-led, Reform congregation until 1977, when they hired Abraham Shusterman. In 1980, the congregation added educational and social facilities to the building and changed its name to Temple Shalom.

Ark and Torahs at Temple Judea, Fort Myers, c. 2019. Courtesy of the congregation.

Ark and Torahs at Temple Judea, Fort Myers, c. 2019. Courtesy of the congregation.

As cities and developments in Charlotte, Lee, and Collier Counties grew, a series of new congregations formed. By the end of the 1970s, Lee County was home to more than 600 Jewish families and four synagogues. In Cape Coral, Temple Beth Shalom split from Temple Beth El in 1971. When Temple Beth Shalom was ready to build a new synagogue in 1978, the Rosen Brothers donated land and $5,000 toward the project, making them patrons of both Reform congregations. In the early 1970s another group of area Jews began to hold more traditional services in private homes and then at a Fort Myers high school. The new congregation, Temple Judea, affiliated with the Conservative movement. It occupied a storefront space in the late 1970s and then moved to a new synagogue in the early 1980s. Temple Judea was the only Jewish congregation in Fort Myers city limits for many years, until Temple Beth El relocated to Fort Myers in 1994.

Elsewhere in the area, snowbirds and retirees drove the creation of new congregations. In the North Port and Port Charlotte area, snowbirds founded a Conservative congregation, Temple Beth El, in the early 1970s. According to congregational history, the group started meeting when a seasonal resident gathered a minyan to say kaddish for his brother. At the southern edge of the three-county area, just outside the Everglades, a group of approximately 60 Jews organized the Jewish Congregation of Marco Island in the early 1980s. Sanibel Island Jews founded Temple Bat Yam in 1991. Both the Sanibel and Marco Island congregations are primarily adult congregations. Chabad developed a center in Fort Myers beginning in the mid-1990s, and there are currently four chabad locations in the three-county region.

Elsewhere in the area, snowbirds and retirees drove the creation of new congregations. In the North Port and Port Charlotte area, snowbirds founded a Conservative congregation, Temple Beth El, in the early 1970s. According to congregational history, the group started meeting when a seasonal resident gathered a minyan to say kaddish for his brother. At the southern edge of the three-county area, just outside the Everglades, a group of approximately 60 Jews organized the Jewish Congregation of Marco Island in the early 1980s. Sanibel Island Jews founded Temple Bat Yam in 1991. Both the Sanibel and Marco Island congregations are primarily adult congregations. Chabad developed a center in Fort Myers beginning in the mid-1990s, and there are currently four chabad locations in the three-county region.

Twenty-First Century

In the early 2000s, Southwest Florida entered another period of real estate speculation and rapid growth. Marcia Jo Zerivitz, a historian of Florida Jews, wrote that Naples and Collier County may have been the fastest growing Jewish community in Florida as of 2005. Although the 2008 mortgage crisis, which hit the area especially hard, may have dampened that growth, Southwest Florida continues to support a significant and stable Jewish community.

In 2019, the American Jewish Year Book estimated the year-round Jewish population of Lee, Charlotte, and Collier Counties at approximately 12,000 individuals, with a few thousand more Jews likely there as part-time residents. There are fifteen Jewish congregations in the area, at least two Jewish humanistic groups, and a full variety of Jewish social, cultural, and educational organizations.

In 2019, the American Jewish Year Book estimated the year-round Jewish population of Lee, Charlotte, and Collier Counties at approximately 12,000 individuals, with a few thousand more Jews likely there as part-time residents. There are fifteen Jewish congregations in the area, at least two Jewish humanistic groups, and a full variety of Jewish social, cultural, and educational organizations.

Additional Resources

Virtual Museum of Southwest Florida Jewish History

Virtual Museum of Southwest Florida Jewish History