Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Panama City, FL

Overview

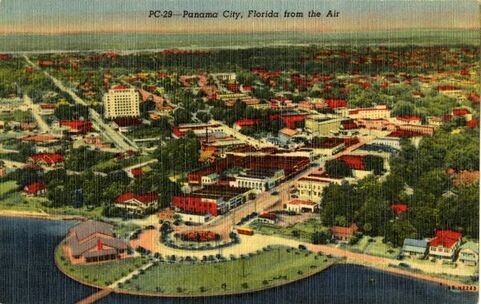

Aerial view of Panama City, 1946. State Archives of Florida

Aerial view of Panama City, 1946. State Archives of Florida

Panama City, the seat of Bay County, developed a Jewish community slowly over the course of the 20th century. Although the growth of Tyndall Air Force Base brought in additional residents in the 1940s, local Jews did not establish their own congregation until the 1990s. By that point, Panama City Beach boasted a growing tourism industry and had gained notoriety as a popular spring break destination. In the early 21st century, a second congregation formed to offer Orthodox services to the small Sephardic-Israeli community of Panama City Beach. Both congregations faced setbacks, however, in the wake of Hurricane Michael, which caused widespread damage in the area in October 2018.

Early Jewish Settlement

Although Euro-American settlers arrived in the vicinity in the early nineteenth century, the Panama City area, now part of Bay County, remained rural and largely undeveloped for nearly one hundred years. Logging was the first major local industry, and the extension of rail lines to Panama City beginning in 1908 spurred population increases and economic growth over the following decades. The construction of new highways and bridges in the 1920s allowed tourists to visit the white sand beaches across Saint Andrew Bay.

The first known Jews in the area had arrived by the mid-1910s, but they settled first in small, inland towns of Bonifay and Chipley (just north of the eventual route of Interstate 10). Sam Laken lived in Bonifay with his first wife, Rose (Schneider), who died in 1929, not long after the birth of their fourth child. Sam then married Rose’s sister Bessie, herself a widow with prior children. In nearby Chipley, Rose and Bessie’s brother Morris Schneider and his wife Bessie (Yoffe) owned and operated Schneider’s Department store from the mid-1910s until 1949. Chipley was home to at least two other Jewish families in the early twentieth century, the Leaders and the Rubensteins.

The first known Jews in the area had arrived by the mid-1910s, but they settled first in small, inland towns of Bonifay and Chipley (just north of the eventual route of Interstate 10). Sam Laken lived in Bonifay with his first wife, Rose (Schneider), who died in 1929, not long after the birth of their fourth child. Sam then married Rose’s sister Bessie, herself a widow with prior children. In nearby Chipley, Rose and Bessie’s brother Morris Schneider and his wife Bessie (Yoffe) owned and operated Schneider’s Department store from the mid-1910s until 1949. Chipley was home to at least two other Jewish families in the early twentieth century, the Leaders and the Rubensteins.

Rose Shirley Schneider (later Shirley Sonne) with an African American domestic worker, 1933. The woman is identified only as "Willie." State Archives of Florida.

Rose Shirley Schneider (later Shirley Sonne) with an African American domestic worker, 1933. The woman is identified only as "Willie." State Archives of Florida.

In the early 1920s, Panama City attracted additional members of the Schneider family to the Florida Panhandle. Karl and Bluma Schneider were both immigrants from the Russian Empire who had lived in New York City and Alabama before arriving in Florida. According to family history, they lived in Ocala for a time, but then moved to Panama City despite warnings that “Jews were not welcome there.” When Karl and Bluma had their fourth child, Rose Shirley Schneider, in 1930, she was likely the first Jewish child to be born in Panama City. A third branch of the Schneider family moved to nearby Port St. Joe shortly after Shirley’s birth, and the extended family gathered weekly for Sunday dinners.

Decades later, Shirley reflected on the challenges of growing up in a place with such a small Jewish population, writing that, among non-Jews, “there were a good many stories told about the blond Jew baby and much speculation about where the horns were.” Although she did not experience “overt anti-Semitism,” she was excluded from some social clubs. Her three older brothers told her that “there were a great many fights when they first came to Panama City and entered school.” Their parents overcame local prejudices and became active in community organizations. Shirley felt that local non-Jews viewed them as an exception to Jewish stereotypes, however, and that a generalized anti-Semitism persisted in the community.

Decades later, Shirley reflected on the challenges of growing up in a place with such a small Jewish population, writing that, among non-Jews, “there were a good many stories told about the blond Jew baby and much speculation about where the horns were.” Although she did not experience “overt anti-Semitism,” she was excluded from some social clubs. Her three older brothers told her that “there were a great many fights when they first came to Panama City and entered school.” Their parents overcame local prejudices and became active in community organizations. Shirley felt that local non-Jews viewed them as an exception to Jewish stereotypes, however, and that a generalized anti-Semitism persisted in the community.

The Mid-20th Century

By 1940, a handful of other Jewish families arrived in Panama City and surrounding towns, but the population was unstable. The Wengrow family managed a Panama City department store in the 1930s, lived in Birmingham and Pensacola for much of the 1940s, and returned to Panama City, where they owned a liquor store, in the 1950s. Abe and Helen Eisenson operated a dry cleaning business there in the early 1940s. (The business did not last, but they stayed in town.) When Karl Schneider died in an automobile collision in 1937, Bluma remarried, moved with her new husband and Shirley to New York City for three years, and then returned to Panama City.

For much of the twentieth century, Jews in Panama City and Bay County travelled north to Dothan, Alabama, when they wanted to attend synagogue. Dothan’s Temple Emanu-El was closer and easier to get to than synagogues in Pensacola or Tallahassee, and local families celebrated bar mitzvahs and confirmations there.

World War II brought continued development to the area, as well as an influx of Jewish military personnel, who were stationed at Tyndall Field (now Tyndall Air Force Base). The rabbi from Dothan served service members and taught local Jewish children during the war and immediately after, and civilian Jews helped coordinate Passover seders held in the Tyndall mess hall.

The Jewish population grew enough in the 1940s and 1950s that local Jews considered starting a congregation. Shirley Schneider’s step-father, Jack Tashlik, led occasional services in Jewish homes, but the community was not yet large enough to support a synagogue. For several decades, Bay County Jews continued to make monthly trips to Dothan for shabbat services and held high holiday observances at Tyndall Air Force Base. Hy Wakstein, a local business owner, later recalled that he “wore out a car” with weekly trips to Dothan for his son’s religious education.

For much of the twentieth century, Jews in Panama City and Bay County travelled north to Dothan, Alabama, when they wanted to attend synagogue. Dothan’s Temple Emanu-El was closer and easier to get to than synagogues in Pensacola or Tallahassee, and local families celebrated bar mitzvahs and confirmations there.

World War II brought continued development to the area, as well as an influx of Jewish military personnel, who were stationed at Tyndall Field (now Tyndall Air Force Base). The rabbi from Dothan served service members and taught local Jewish children during the war and immediately after, and civilian Jews helped coordinate Passover seders held in the Tyndall mess hall.

The Jewish population grew enough in the 1940s and 1950s that local Jews considered starting a congregation. Shirley Schneider’s step-father, Jack Tashlik, led occasional services in Jewish homes, but the community was not yet large enough to support a synagogue. For several decades, Bay County Jews continued to make monthly trips to Dothan for shabbat services and held high holiday observances at Tyndall Air Force Base. Hy Wakstein, a local business owner, later recalled that he “wore out a car” with weekly trips to Dothan for his son’s religious education.

Organized Jewish Life

Finally, in the early 1990s, area Jews began to organize their own congregation. Sonny and Alma Glass moved to Panama City in 1991 when he took a job with a furniture company. They attended Rosh Hoshanah and Yom Kippur services at the base and, although the services drew a respectable crowd, wanted something more. Not long after, Jewish residents organized a cookout in Panama City Beach and advertised the event on television and in local newspapers. On November 18, 1992, Don and Marilyn Nations hosted a meeting at which the participants founded the Bay Jewish Community.

In 1993, they held their first community Passover seder at the Holy Nativity Episcopal Church, which served as the site of weekly shabbat services. Tyndall Air Force Base provided prayer books and other judaica. That fall, the community held twice monthly religious school classes at the home of Greg Yordon, and in 1994 the Bay Jewish Community changed its name to Temple B’nai Israel. For the next several years, they met in churches, hotels, and other borrowed spaces for Sunday school, holidays, and lifecycle events. Temple B’nai Israel is a Reform congregation, although its members come from a variety of backgrounds and may personally identify with other movements. The congregation reached a membership of over forty families by 2001, nearly half of the estimated Jewish households in Bay County at that time. They also began plans to construct their own synagogue on two acres of land that had been donated in 2000.

In 1993, they held their first community Passover seder at the Holy Nativity Episcopal Church, which served as the site of weekly shabbat services. Tyndall Air Force Base provided prayer books and other judaica. That fall, the community held twice monthly religious school classes at the home of Greg Yordon, and in 1994 the Bay Jewish Community changed its name to Temple B’nai Israel. For the next several years, they met in churches, hotels, and other borrowed spaces for Sunday school, holidays, and lifecycle events. Temple B’nai Israel is a Reform congregation, although its members come from a variety of backgrounds and may personally identify with other movements. The congregation reached a membership of over forty families by 2001, nearly half of the estimated Jewish households in Bay County at that time. They also began plans to construct their own synagogue on two acres of land that had been donated in 2000.

Temple B'nai Israel, prior to its dedication in 2003. Courtesy of the congregation.

Temple B'nai Israel, prior to its dedication in 2003. Courtesy of the congregation.

At the synagogue dedication in 2003, congregants, friends, and local officials celebrated the Jewish community’s new home. Mayor Gerry Clemons remarked that the new facility would help the city attract businesses and workers. Sonny Glass, who acted for 14 years as the local para-rabbi, expressed his “pride and satisfaction at becoming a visible part of the community.” A few years later, Temple B’nai Israel received unexpected help in paying off their mortgage when an anonymous, non-Jewish donor made a series of unsolicited donations—each one delivered as a “brick” of cash which had apparently been buried and then dug up.

By the time Temple B’nai Israel became organized, Panama City Beach had risen in prominence as a tourist destination, especially for college students on spring break. (MTV’s Spring Break broadcast from Panama City Beach in 1996 and 1997.) Among the business owners and workers who migrated to the area to serve tourists were a significant number of young Israelis, who began arriving in the late 1980s and operated beachfront t-shirt shops and other businesses. A few Israeli families attended Temple B’nai Israel, but found that American Reform Judaism did not entirely fit their needs. The group—which included Israeli families of Moroccan, Yemeni, and Ethiopian descent—began to hold traditional Sephardic services in local homes in the early 2000s, and around 2004 they established a small Sephardic Orthodox congregation in a beachside storefront. The congregation changed its name to Achdut Israel and moved to another building in approximately 2007. They opened a mikvah there in 2015. Achdut Israel attracts area Jews who prefer a Hebrew service and Orthodox halachic practice, including the separation of men and women during prayer services and traditional divisions of gender roles in leadership. They had to close their synagogue in 2018, however, and members began to hold services in a rented office space. In early 2019, Chabad opened a new center in Panama City Beach, which serves Achdut Israel and now operates the mikvah.

By the time Temple B’nai Israel became organized, Panama City Beach had risen in prominence as a tourist destination, especially for college students on spring break. (MTV’s Spring Break broadcast from Panama City Beach in 1996 and 1997.) Among the business owners and workers who migrated to the area to serve tourists were a significant number of young Israelis, who began arriving in the late 1980s and operated beachfront t-shirt shops and other businesses. A few Israeli families attended Temple B’nai Israel, but found that American Reform Judaism did not entirely fit their needs. The group—which included Israeli families of Moroccan, Yemeni, and Ethiopian descent—began to hold traditional Sephardic services in local homes in the early 2000s, and around 2004 they established a small Sephardic Orthodox congregation in a beachside storefront. The congregation changed its name to Achdut Israel and moved to another building in approximately 2007. They opened a mikvah there in 2015. Achdut Israel attracts area Jews who prefer a Hebrew service and Orthodox halachic practice, including the separation of men and women during prayer services and traditional divisions of gender roles in leadership. They had to close their synagogue in 2018, however, and members began to hold services in a rented office space. In early 2019, Chabad opened a new center in Panama City Beach, which serves Achdut Israel and now operates the mikvah.

Disaster and Recover

On October 10, 2018, Hurricane Michael reached the Florida Panhandle, first making landfall southeast of Panama City, between Tyndall Air Force Base and Mexico Beach. The Category 5 storm caused massive damage across the area and resulted in at least 50 deaths in Florida. Neither congregation suffered major direct losses in the storm, either in terms of judaica or property, but the hurricane directly affected all of their congregants, as it did the general population of Bay County. Michael damaged Jewish homes and businesses to varying degrees, with some houses and buildings rendered salvageable. Several Jewish families, including longtime leaders such as Sonny and Alma Glass, moved away in the storms aftermath, while others face a long recovery. Repairs to Temple B’nai Israel took until summer 2019 to complete. In the meantime, the congregation made arrangements to share their space with Unity Spiritual Center of Panama City, whose building took significant damage during the storm.

While the Jewish community of Panama City and Panama City Beach has benefited from the support of Jewish individuals and groups in Florida and beyond, the area will take years to recover. Hurricane Michael transformed the physical landscape of Bay County, and it remains to be seen what its long-term effects on the local Jewish community will be.

While the Jewish community of Panama City and Panama City Beach has benefited from the support of Jewish individuals and groups in Florida and beyond, the area will take years to recover. Hurricane Michael transformed the physical landscape of Bay County, and it remains to be seen what its long-term effects on the local Jewish community will be.