Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Vicksburg, Mississippi

Overview >> Mississippi >> Vicksburg

|

Overview

Vicksurg, the seat of Warren County, emerged as the second largest city in the state (behind Natchez) by 1840. The riverport town grew due to its strong commercial and industrial economies and served as an important steamboat stop. As a local trade center Vicksburg connected nearby farms to points up- and downriver, and it was home to a significant market for the trade of enslaved people. The city is best known for the major Civil War battle fought there in 1863, which resulted in a United States Army victory and solidified Union control of the Mississippi River.

Jews began to arrive in Vicksburg early in its history, and the city eventually became home to one of the first organized Jewish communities in Mississippi. Vicksburg’s Jewish history mirrors other Mississippi towns and cities: Jewish retailers and other business people arrived during periods of growth and once played significant roles in local civic and economic life, but the Jewish population dwindled in the late 20th century. As of 2022 Vicksburg’s historic Reform congregation, Anshe Chesed, continues to meet regularly with a small group of worshipers. |

Early Jewish Settlers

It is not clear when Jews first arrived in Vicksburg, but a small Jewish population began to settle there by at least the 1830s. (Some histories indicate that Jews were present when the town incorporated in 1825.) An estimated 25-30 Jewish families lived in Vicksburg around 1840. Among those present before 1840 were the Yoste, Cohen, Wolfson, and Lorch families. Like other 19th-century Jewish migrants in and beyond the South, the first Vicksburg Jews concentrated in trade and retail occupations.

Bernard Cohen and his wife, Rachel (Lorch) Cohen arrived in town around 1838 from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Her father, Benedict Lorch, lived in the area or at least owned property there, and Rachel’s sister Caroline Lorch married Jacob Wolfson in Vicksburg in 1838. Jews throughout the United States were highly mobile during this period, and those in Vicksburg were no exception; few of the pre-1840 Jews became active in the emerging Jewish community, and after Bernard Cohen died in 1844, his family relocated to Cincinnati.

Bernard Yoste stands out among the earliest arrivals for his longtime role as a Jewish communal leader. By 1840 he was married to a Catholic woman named Mary, had three children (out of an eventual six), and enslaved three Black workers. He was one of the wealthiest local Jews, and beginning in the 1840s he provided a space for Jewish religious services on the second floor of a warehouse he owned on Levee Street. Yoste also served as a lay leader, but, despite his religious activity, his children seem to have been raised Catholic.

Another notable early settler was M. A. Levy, who served as a city selectman in 1832 and 1833. Louis Levy and David Brown arrived in 1834, and were closely followed by Julius Hornthal and Abraham Aaron.

Bernard Cohen and his wife, Rachel (Lorch) Cohen arrived in town around 1838 from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Her father, Benedict Lorch, lived in the area or at least owned property there, and Rachel’s sister Caroline Lorch married Jacob Wolfson in Vicksburg in 1838. Jews throughout the United States were highly mobile during this period, and those in Vicksburg were no exception; few of the pre-1840 Jews became active in the emerging Jewish community, and after Bernard Cohen died in 1844, his family relocated to Cincinnati.

Bernard Yoste stands out among the earliest arrivals for his longtime role as a Jewish communal leader. By 1840 he was married to a Catholic woman named Mary, had three children (out of an eventual six), and enslaved three Black workers. He was one of the wealthiest local Jews, and beginning in the 1840s he provided a space for Jewish religious services on the second floor of a warehouse he owned on Levee Street. Yoste also served as a lay leader, but, despite his religious activity, his children seem to have been raised Catholic.

Another notable early settler was M. A. Levy, who served as a city selectman in 1832 and 1833. Louis Levy and David Brown arrived in 1834, and were closely followed by Julius Hornthal and Abraham Aaron.

The Beginnings of a Jewish Community

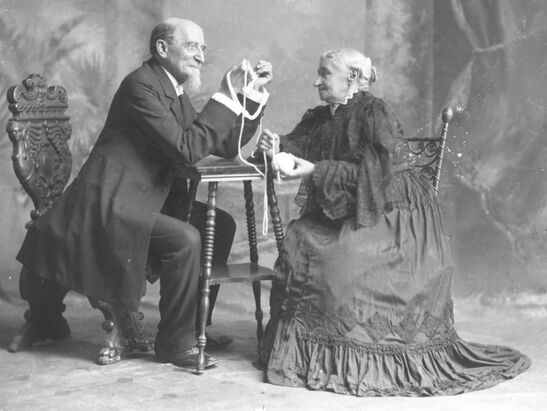

Philip and Sophia Sartorius.

Philip and Sophia Sartorius.

The organized Jewish community of Vicksburg dates to at least 1841, when local Jews formed the Hebrew Benevolent Congregation of the Men of Mercy. Although the group did not legally incorporate, they met regularly under the leadership of Bernard Yoste, first in private homes and then above the warehouse he owned. The congregation was the first in Mississippi, although B’nai Israel in Natchez was the first to receive a charter from the state.

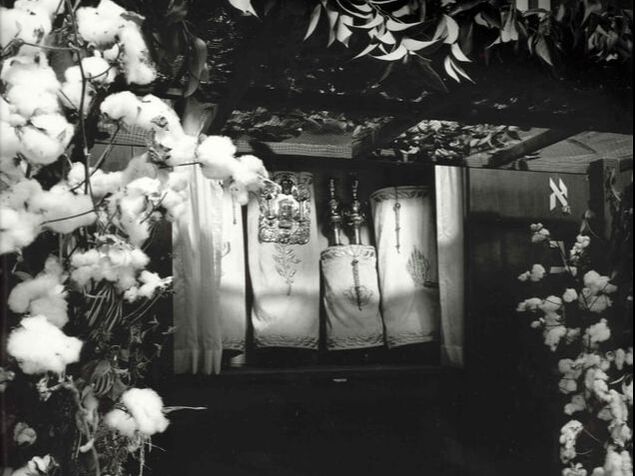

Religious services initially followed traditional Ashkenazi practice, with prayers recited in Hebrew. Local histories credit the Sartorius brothers—Isaac, Jacob, and Philip—with bringing two Torah scrolls to the emerging Jewish community. The brothers came from Bavaria, and both Torah scrolls were purchased in Frankfurt by another brother, Wolf Sartorius. Jacob brought one when he immigrated around 1842, and Philip brought the other in 1845. Philip later wrote that when he arrived the small congregation consisted of perhaps a dozen families and only held services at the high holidays. They employed a shochet (kosher slaughterer) and observed traditional dietary restrictions. The shochet also acted as a cantor.

The small Jewish community persisted through the 1840s and 1850s. While their population may have grown somewhat, Jewish immigrants also moved frequently from one town to another. Philip Sartorius lived briefly in Princeton, Mississippi, and later settled at Milliken’s Bend, Louisiana, a small community a short distance upriver from Vicksburg, where he lived until sometime during the Civil War. His brother Jacob joined him there in the early 1850s but left a few years later during a deadly outbreak of yellow fever. Jacob Sartorius even moved his family back to Germany for a time but ultimately returned to the United States. Isaac Sartorius, meanwhile, moved with his family to New York City in 1958.

Religious services initially followed traditional Ashkenazi practice, with prayers recited in Hebrew. Local histories credit the Sartorius brothers—Isaac, Jacob, and Philip—with bringing two Torah scrolls to the emerging Jewish community. The brothers came from Bavaria, and both Torah scrolls were purchased in Frankfurt by another brother, Wolf Sartorius. Jacob brought one when he immigrated around 1842, and Philip brought the other in 1845. Philip later wrote that when he arrived the small congregation consisted of perhaps a dozen families and only held services at the high holidays. They employed a shochet (kosher slaughterer) and observed traditional dietary restrictions. The shochet also acted as a cantor.

The small Jewish community persisted through the 1840s and 1850s. While their population may have grown somewhat, Jewish immigrants also moved frequently from one town to another. Philip Sartorius lived briefly in Princeton, Mississippi, and later settled at Milliken’s Bend, Louisiana, a small community a short distance upriver from Vicksburg, where he lived until sometime during the Civil War. His brother Jacob joined him there in the early 1850s but left a few years later during a deadly outbreak of yellow fever. Jacob Sartorius even moved his family back to Germany for a time but ultimately returned to the United States. Isaac Sartorius, meanwhile, moved with his family to New York City in 1958.

The Civil War

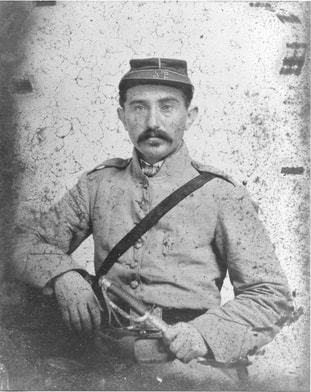

Leon Fischel in Confederate Uniform.

Leon Fischel in Confederate Uniform.

Prior to the Civil War, most Jews in and around Vicksburg held similar views about enslavement as other white southerners. Bernard Yoste enslaved nine Black people in 1860, and Philip Sartorius enslaved a handful of “servants” in nearby Milliken’s Bend. These examples typify Jewish slave owners in the South, who tended not to own the sorts of large properties that required dozens (or hundreds) of workers.

At least one Jewish woman in the area objected to slavery. Henrietta Bauer (or Bower) was a Bavarian native who settled in Milliken’s Bend with her husband in 1845. When the Civil War broke out in 1861 she was single and had three children. Not long after the start of the war she left the small town for a settlement on Island 102 in the Mississippi River, which was under Union control. Bauer reportedly held abolitionist views, and she lived and worked with a small community of Black refugees who had escaped enslavement and also sought safety on the island.

Census records from 1860 do not indicate that most Vicksburg Jews owned Black slaves, but they did serve in the Confederate Army in significant numbers. Leon Fischel (pictured) served as aide to Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnson and later named a son after the general. Philip Sartorius avoided service for as long as he could but was eventually wounded at Milliken’s Bend during the Union campaign on Vicksburg. Other wounded Jewish Confederates included Herman Nauen and Louis Hornthal, both of whom came from prominent Jewish families.

At least one Jewish woman in the area objected to slavery. Henrietta Bauer (or Bower) was a Bavarian native who settled in Milliken’s Bend with her husband in 1845. When the Civil War broke out in 1861 she was single and had three children. Not long after the start of the war she left the small town for a settlement on Island 102 in the Mississippi River, which was under Union control. Bauer reportedly held abolitionist views, and she lived and worked with a small community of Black refugees who had escaped enslavement and also sought safety on the island.

Census records from 1860 do not indicate that most Vicksburg Jews owned Black slaves, but they did serve in the Confederate Army in significant numbers. Leon Fischel (pictured) served as aide to Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnson and later named a son after the general. Philip Sartorius avoided service for as long as he could but was eventually wounded at Milliken’s Bend during the Union campaign on Vicksburg. Other wounded Jewish Confederates included Herman Nauen and Louis Hornthal, both of whom came from prominent Jewish families.

The Late 19th Century

Vicksburg grew dramatically during and immediately after the Civil War, reaching a population of more than 12,000 people in 1870, and the surrounding countryside attracted large numbers of recently freed Black workers in the decades following the war. In 1880 Warren County also boasted the state’s largest immigrant population—mostly natives of Ireland and Germany. Vicksburg remained a major commercial hub and was relatively industrialized compared to other cities in Mississippi.

The Vicksburg Jewish community grew along with the city. By the end of the Civil War there were 90 Jewish families in town and 35 Jewish-owned stores. The most recent Jewish immigrants had come from Prussia and Poland. Both newcomers and American-born Jewish residents concentrated in retail; Jews owned stores that sold dry goods, furniture, jewelry, hardware, groceries, and medicine. Business success led to civic leadership, and Bazinsky Road, Kiersky Street, and Marcus Street are all named for prominent local Jews from the mid- and late 19th century. In addition to Jewish-owned stores, local Jews also operated saloons and horse stables

The Vicksburg Jewish community grew along with the city. By the end of the Civil War there were 90 Jewish families in town and 35 Jewish-owned stores. The most recent Jewish immigrants had come from Prussia and Poland. Both newcomers and American-born Jewish residents concentrated in retail; Jews owned stores that sold dry goods, furniture, jewelry, hardware, groceries, and medicine. Business success led to civic leadership, and Bazinsky Road, Kiersky Street, and Marcus Street are all named for prominent local Jews from the mid- and late 19th century. In addition to Jewish-owned stores, local Jews also operated saloons and horse stables

Despite the uncertainties of the war years, the Jewish community became more organized during the period, formally incorporating as Anshe Chesed (People of Loving Kindness) in 1862. They dedicated their first synagogue in 1870. Vicksburg Jews formed several other Jewish organizations, including a Ladies Hebrew Benevolent Society in 1866 and a local chapter of B’nai B’rith (a Jewish fraternal organization) in 1867.

In 1871, Vicksburg Jews formed the Young Men’s Hebrew Benevolent Association, which they later renamed the B’nai B’rith Literary Association. The “B.B. Club,” as it was known, served as the social center for Vicksburg’s Jewish community. Their original building was located on Cherry and Crawford Streets. After the first building was destroyed in a 1915 fire, the group erected a new building on Clay and Walnut Streets. It was handsomely equipped for Jewish social engagements, including a swimming pool, meeting rooms, a fine dining room, a ballroom, and a library.

The presence of the B.B. Club reflected a level of social separation between Jews and white Christians, but Jews enjoyed a relatively high level of civic inclusion overall. As traders and merchants, Jews (along with business owners from other ethnic groups) played an important role by supplying retail goods to townspeople and rural residents of various economic strata. Jewish names marked prominent businesses in the city’s shopping district, and local Jews belonged to fraternal organizations such as Knights of Pythias, the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks, and the International Order of Odd Fellows.

In 1871, Vicksburg Jews formed the Young Men’s Hebrew Benevolent Association, which they later renamed the B’nai B’rith Literary Association. The “B.B. Club,” as it was known, served as the social center for Vicksburg’s Jewish community. Their original building was located on Cherry and Crawford Streets. After the first building was destroyed in a 1915 fire, the group erected a new building on Clay and Walnut Streets. It was handsomely equipped for Jewish social engagements, including a swimming pool, meeting rooms, a fine dining room, a ballroom, and a library.

The presence of the B.B. Club reflected a level of social separation between Jews and white Christians, but Jews enjoyed a relatively high level of civic inclusion overall. As traders and merchants, Jews (along with business owners from other ethnic groups) played an important role by supplying retail goods to townspeople and rural residents of various economic strata. Jewish names marked prominent businesses in the city’s shopping district, and local Jews belonged to fraternal organizations such as Knights of Pythias, the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks, and the International Order of Odd Fellows.

Jews also held elected office on a regular basis. Nathan J. Bazinsky ran for Warren County Chancery Clerk in 1887 as a Democrat, defeating incumbent Republican George T. Hardy despite attacks on him for his Jewish identity. (The Democratic Party had recently regained power in the state following the end of Reconstruction, and its supporters sought to reassert white political and economic dominance.) Abe Kiersky served as City Tax Assessor from 1889 to 1937. In October 1891, a correspondent from Vicksburg wrote in the American Israelite that “while the Jews here form only about three percent of the population, they claim a magistrate and alderman, the town clerk and the chancery clerk.” The notice goes on to say that the Jewish population was generally prosperous but not wealthy, and that “there is not a single Jewish family receiving charity.”

Religious Life

Within a few years of the incorporation of Anshe Chesed, the Vicksburg Jewish community purchased a cemetery site on Grove Street, which later became part of the Vicksburg National Military Park. The burial site was actually the second Jewish cemetery in the town; the location of the original cemetery is unknown, and it may have been damaged by Union shelling during the Siege of Vicksburg. The community purchased the Grove Street location in 1864, and burials continue there as of the early 21st century. Records also indicate that a number of Jewish remains were disinterred from their original sites and reburied at the new cemetery.

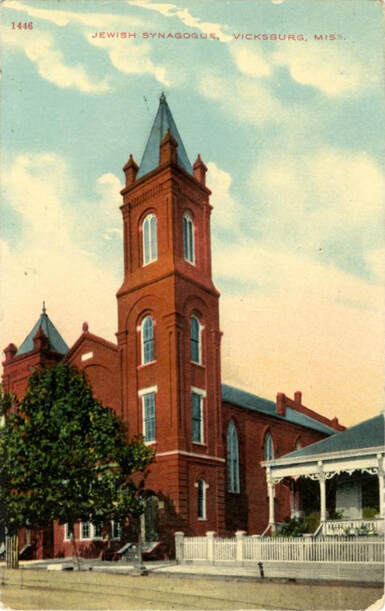

The 1870 Anshe Chesed synagogue on Cherry Street, early 20th century. Cooper Postcard Collection, Mississippi Department of Archives and History

The 1870 Anshe Chesed synagogue on Cherry Street, early 20th century. Cooper Postcard Collection, Mississippi Department of Archives and History

The members of Anshe Chesed hired their first rabbi in 1866. Rabbi Bernhard Henry Gotthelf and his wife Sophie Launauer Gotthelf came from Bavaria, as had a number of local families. He had served as a chaplain in the Union army (which the local congregants did not hold against him) and worked in Louisville, Kentucky, before the Vicksburg congregation hired him for a salary of $40 per month. Under Gotthelf’s leadership, the congregation moved away from orthodox tradition and fully adopted Reform Judaism in 1873 when they became a charter member of the new Union of American Hebrew Congregations.

When the congregation dedicated their first synagogue on Cherry Street in May 1870, ceremonies included a parade, speeches, and a grand banquet. Rabbi Max Lillienthal of Cincinnati spoke to the assembled crowd, and guests included Mississippi Governor James Alcorn, the mayor of Vicksburg, and other state and local officials. Several white Christian clergy also participated in the ceremony. A local newspaper called the occasion “a day of gladness and joy, such as we will naturally feel on having accomplished a good object.”

While the economic and population growth of the 1860s suggested a period of prosperity and continued development for the local Jewish community, life in Vicksburg remained challenging. Yellow fever once again swept through the area in 1871 and 1878. The 1871 outbreak claimed 11 Jewish lives, and 46 local Jews—as much as one third of the local Jewish population—died in the 1878 epidemic. In the aftermath of the yellow fever outbreak and the economic damage it caused, the membership of Anshe Chesed reportedly shrank from 76 households to around fifty. Among the dead was Rabbi Bernard Gotthelf, and Levi M. Lowenberg assumed the role of lay leader for the considerably diminished community.

Rabbi Aron (or Aaron) Suhler stepped into the Anshe Chesed pulpit in 1879, a period of deep grief and economic hardship due to the recent epidemic. Born in Bavaria, he had served congregations in Akron, Ohio, and Dallas, Texas, before arriving in Vicksburg. He remained with Anshe Chesed until 1883, when he took a job in Waco.

Rabbi Herman Bien arrived in 1883 and became known as the “poet rabbi” because he published several volumes of poetry. After Anshe Chesed moved to replace Rabbi Bien in 1895, he committed suicide in Birmingham, Alabama, after being rejected for a rabbinical position there.

When the congregation dedicated their first synagogue on Cherry Street in May 1870, ceremonies included a parade, speeches, and a grand banquet. Rabbi Max Lillienthal of Cincinnati spoke to the assembled crowd, and guests included Mississippi Governor James Alcorn, the mayor of Vicksburg, and other state and local officials. Several white Christian clergy also participated in the ceremony. A local newspaper called the occasion “a day of gladness and joy, such as we will naturally feel on having accomplished a good object.”

While the economic and population growth of the 1860s suggested a period of prosperity and continued development for the local Jewish community, life in Vicksburg remained challenging. Yellow fever once again swept through the area in 1871 and 1878. The 1871 outbreak claimed 11 Jewish lives, and 46 local Jews—as much as one third of the local Jewish population—died in the 1878 epidemic. In the aftermath of the yellow fever outbreak and the economic damage it caused, the membership of Anshe Chesed reportedly shrank from 76 households to around fifty. Among the dead was Rabbi Bernard Gotthelf, and Levi M. Lowenberg assumed the role of lay leader for the considerably diminished community.

Rabbi Aron (or Aaron) Suhler stepped into the Anshe Chesed pulpit in 1879, a period of deep grief and economic hardship due to the recent epidemic. Born in Bavaria, he had served congregations in Akron, Ohio, and Dallas, Texas, before arriving in Vicksburg. He remained with Anshe Chesed until 1883, when he took a job in Waco.

Rabbi Herman Bien arrived in 1883 and became known as the “poet rabbi” because he published several volumes of poetry. After Anshe Chesed moved to replace Rabbi Bien in 1895, he committed suicide in Birmingham, Alabama, after being rejected for a rabbinical position there.

Rabbi George Solomon, who replaced Rabbi Bien, was known for riding a bicycle as his preferred mode of transportation. He was the first American-born rabbi to serve Anshe Chesed. In addition to his congregational duties, he operated a private high school in Vicksburg, which served as an alternative to what he viewed as the “deplorable state of public education.” After ending his tenure in Vicksburg in 1903, Rabbi Solomon moved on to Congregation Mikveh Israel in Savannah, Georgia, where he served for more than four decades.

The Early 20th Century

Shortly after Rabbi Solomon’s departure, Anshe Chesed claimed a membership of 132 families, and one estimate placed the Vicksburg Jewish population at more than 600 individuals. As in other cities across the United States, a growing proportion of new Jewish arrivals hailed from Eastern Europe, and some of the newcomers sought to establish an Orthodox congregation. They founded Beth Israel Congregation in 1901, and the group had 27 member families in 1907. Rabbi Solomon from Anshe Chesed conducted services for the traditional congregation on the second day of Rosh Hashanah that year. (American Reform Jews traditionally observe only one day of Rosh Hashanah, whereas most other denominations observe two.) Records reflect a second attempt to organize an Orthodox congregation in 1906, this time under the name Congregation Ahavas Achim (Congregation of Brotherly Love). The relationship between the two groups is unclear, but neither congregation proved long-lasting. Orthodox Jews in Vicksburg eventually joined Anshe Chesed, and an early-20th-century survey response by Rabbi Kory characterized traditional practices in the city as “strictly kitchen Orthodoxy,” indicating that ritual life for recent East European Jews consisted mostly of adherence to traditional dietary laws.

Rabbi Solomon’s participation in Orthodox Rosh Hashanah services proved an unexceptional event in Vicksburg, and historian Lee Shai Weissbach notes that the Reform congregation made notable efforts to welcome newcomers to the city. Solomon’s long-tenured successor, Rabbi Sol Kory, permitted worshippers to wear yarmulkes in the Anshe Chesed sanctuary—a practice that was forbidden in many other Reform temples—and the community kept kittels on hand at the synagogue. (A kittel is a white shroud traditionally worn by men on special occasions and used for burial). While the Orthodox congregations dissolved well before Rabbi Stanley Brav replaced Rabbi Kory in 1937, Orthodox worship continued in Vicksburg. Rabbi Brav wrote in his autobiography that he attended minyans in Orthodox homes and even helped officiate a pidyon haben (ceremonial redeeming of the firstborn son), a practice which was “virtually unheard of in Reform circles.” Brav, who served Anshe Chesed from 1937 until 1948, credited East European immigrants’ integration into Anshe Chesed to Rabbi Kory’s efforts in earlier decades.

The arrival of East European Jews allowed the local Jewish population to remain relatively stable where it might have otherwise shrunk. Anshe Chesed had 200 member households in 1925, and Vicksburg’s estimated Jewish population was reportedly 467 individuals. The congregation also served Jews in nearby towns, including Tallulah and Newellton, Louisiana; Port Gibson, Mississippi (which did have its own small congregation); and small towns at the southern end of the Mississippi Delta.

The arrival of East European Jews allowed the local Jewish population to remain relatively stable where it might have otherwise shrunk. Anshe Chesed had 200 member households in 1925, and Vicksburg’s estimated Jewish population was reportedly 467 individuals. The congregation also served Jews in nearby towns, including Tallulah and Newellton, Louisiana; Port Gibson, Mississippi (which did have its own small congregation); and small towns at the southern end of the Mississippi Delta.

Throughout this period, Jewish businesses retained their prominent role in the city’s downtown shopping district. Lee Shai Weissbach estimates that in 1929 “at least seventeen” of Vicskburg’s 36 dry goods stores were Jewish owned, and a stroll down Washington Street would have passed more than a dozen Jewish businesses, from Paul Kestenbaum’s grocery store and the Rose Drug Company to “J. M Fried’s electrical appliance store” and “Mozart Kaufman’s Electrik Maid Bake Shop.” The city also had a small number of Jewish professionals by that time; in 1920 two Jewish attorneys and one Jewish physician lived in Vicksburg.

Vicksburg’s Jewish population peaked in the 1920s. The Great Depression arrived early in most parts of the South and caused major challenges. In Vicksburg, a number of Jews suspended their memberships to Anshe Chesed, and the congregation cut Rabbi Brav’s salary. Among Jewish businesses that closed during the downturn was the Baer Brothers store, which had been open since the 19th century. Even before the challenges of the Depression years, economic shifts and the mass migration of rural workers to urban areas had begun to reshape small-town life. While Jewish life in Vicksburg remained fairly stable in the following decades, the period of Jewish growth had passed.

Vicksburg’s Jewish population peaked in the 1920s. The Great Depression arrived early in most parts of the South and caused major challenges. In Vicksburg, a number of Jews suspended their memberships to Anshe Chesed, and the congregation cut Rabbi Brav’s salary. Among Jewish businesses that closed during the downturn was the Baer Brothers store, which had been open since the 19th century. Even before the challenges of the Depression years, economic shifts and the mass migration of rural workers to urban areas had begun to reshape small-town life. While Jewish life in Vicksburg remained fairly stable in the following decades, the period of Jewish growth had passed.

The Mid- and Late 20th Century

Although the outmigration of Black farm workers to urban areas contributed to overall population loss in Warren County before 1930, the area’s population rebounded somewhat by 1960. During that period the local Jewish community declined to 250 individuals, but Anshe Chesed’s membership did not fall below 100 households until the late 1970s.

A period of frequent rabbinical turnover reflected the congregation’s declining membership. Following Rabbi Brav’s departure in 1948, a series of four rabbis served terms of two to five years, and the congregation sometimes relied on lay leaders and visiting clergy to hold services. As is common for small congregations with limited financial resources, three of these rabbis came to Vicksburg near the end of their careers. The other, Rabbi Robert Blinder, was only thirty-one years old.

Despite the struggle to secure a long term Rabbi, Anshe Chesed and the local Jewish community remained active during the mid-20th century. Jewish students participated in a local branch of the Southern Federation of Temple Youth (SoFTY) and attended statewide and regional events. At least 29 Jewish youth became confirmed during the 1960s, down somewhat from 40 known confirmands in the 1920s. The Temple Sisterhood, a founding member of the National Federation of Temple Sisterhoods, had been active since 1913 and continued to undertake a variety of tasks in the congregation, administering religious school, organizing onegs (refreshments and informal socialization after services), and overseeing synagogue beautification and upkeep.

The era of rabbinical instability ended in 1966 with the arrival of Rabbi Allan Schwartzman. Rabbi Schwarzman had spent time in Greenville, Mississippi, earlier in the decade, where he served as a military and prison chaplain. In Vicksburg he was known for his popularity with the broader community and is remembered in congregational histories for his liberal attitude towards Black civil rights and racial integration. He also pushed the congregation to build a new synagogue to replace the aging building on Cherry Street.

A period of frequent rabbinical turnover reflected the congregation’s declining membership. Following Rabbi Brav’s departure in 1948, a series of four rabbis served terms of two to five years, and the congregation sometimes relied on lay leaders and visiting clergy to hold services. As is common for small congregations with limited financial resources, three of these rabbis came to Vicksburg near the end of their careers. The other, Rabbi Robert Blinder, was only thirty-one years old.

Despite the struggle to secure a long term Rabbi, Anshe Chesed and the local Jewish community remained active during the mid-20th century. Jewish students participated in a local branch of the Southern Federation of Temple Youth (SoFTY) and attended statewide and regional events. At least 29 Jewish youth became confirmed during the 1960s, down somewhat from 40 known confirmands in the 1920s. The Temple Sisterhood, a founding member of the National Federation of Temple Sisterhoods, had been active since 1913 and continued to undertake a variety of tasks in the congregation, administering religious school, organizing onegs (refreshments and informal socialization after services), and overseeing synagogue beautification and upkeep.

The era of rabbinical instability ended in 1966 with the arrival of Rabbi Allan Schwartzman. Rabbi Schwarzman had spent time in Greenville, Mississippi, earlier in the decade, where he served as a military and prison chaplain. In Vicksburg he was known for his popularity with the broader community and is remembered in congregational histories for his liberal attitude towards Black civil rights and racial integration. He also pushed the congregation to build a new synagogue to replace the aging building on Cherry Street.

In the late 1960s Anshe Chesed sought to construct its new building next to its cemetery in the National Military Park. In order to do so, the congregation secured an act of Congress to authorize a land swap with the National Parks Service, and Sam Klesdorf negotiated an exchange which allowed Anshe Chesed to secure an adequate plot for the synagogue. A groundbreaking service took place in February 1969, and the congregation moved into its new facility in 1970. The single-story building features skylights instead of exterior windows, and a low copper pyramid caps the sanctuary. For large events, the sanctuary and adjoining social hall seat a maximum of 300 people. For a number of years prior to the construction of the new synagogue, the B.B. Club—sold to the congregation in 1950—had hosted large Jewish social events, but the City of Vicksburg purchased the club building in 1967.

Jewish locals remained involved in civic life, including retailer Lee Kuhn, who willed $400,000 dollars in assets to the City Catholic Charity Hospital upon his death in 1953. The gift came with a provision that the hospital serve all people, regardless of race, religion, or financial status. Maurice Emmich served on the Vicksburg Bridge Commission, was president of the local rotary club, and was named “Man of Year” by the Jaycees in 1963. Henry Haas served as county tax assessor in the 1950s and 1960s.

In the late 1960s Anshe Chesed sought to construct its new building next to its cemetery in the National Military Park. In order to do so, the congregation secured an act of Congress to authorize a land swap with the National Parks Service, and Sam Klesdorf negotiated an exchange which allowed Anshe Chesed to secure an adequate plot for the synagogue. A groundbreaking service took place in February 1969, and the congregation moved into its new facility in 1970. The single-story building features skylights instead of exterior windows, and a low copper pyramid caps the sanctuary. For large events, the sanctuary and adjoining social hall seat a maximum of 300 people. For a number of years prior to the construction of the new synagogue, the B.B. Club—sold to the congregation in 1950—had hosted large Jewish social events, but the City of Vicksburg purchased the club building in 1967.

Jewish locals remained involved in civic life, including retailer Lee Kuhn, who willed $400,000 dollars in assets to the City Catholic Charity Hospital upon his death in 1953. The gift came with a provision that the hospital serve all people, regardless of race, religion, or financial status. Maurice Emmich served on the Vicksburg Bridge Commission, was president of the local rotary club, and was named “Man of Year” by the Jaycees in 1963. Henry Haas served as county tax assessor in the 1950s and 1960s.

The Decline of Jewish Vicksburg

While Vicksburg Jews operated dozens of local stores over the years, that number had already shrunk to 14 by 1968. By the early 1980s, Anshe Chesed claimed fewer than 90 member households. A number of remaining Jews in the late 20th century were retirees, while others worked as professionals, including business administrators and engineers, in addition to doctors and lawyers. Rabbi Schwartzman continued to serve the shrinking congregation until he retired to Sarasota, Florida, in 1989. Since then, lay leaders or visiting rabbis have conducted religious services at Anshe Chesed. For more than ten years prior to the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, rabbis from the Institute of Southern Jewish Life led High Holiday services.

As of 2022, the Vicksburg Jewish community remains a small but active group. In 2017 Anshe Chesed deeded its synagogue, cemetery, and some other assets to Friends of Vicksburg National Military Park, a local nonprofit organization. Through an arrangement spearheaded by Stan and Betty Sue Kline, the congregation continues to use the sanctuary and social hall whenever it meets; the park organization uses the classrooms and offices and will maintain the cemetery in perpetuity. The few remaining Jewish businesses include Marcus Furniture, originally opened in 1899, and the Attic Gallery, owned by Lesley Silver. A group of three to four lay people lead weekly Friday night services on a rotating basis, which draw a small crowd of local Jews as well as several non-Jewish supporters.

As of 2022, the Vicksburg Jewish community remains a small but active group. In 2017 Anshe Chesed deeded its synagogue, cemetery, and some other assets to Friends of Vicksburg National Military Park, a local nonprofit organization. Through an arrangement spearheaded by Stan and Betty Sue Kline, the congregation continues to use the sanctuary and social hall whenever it meets; the park organization uses the classrooms and offices and will maintain the cemetery in perpetuity. The few remaining Jewish businesses include Marcus Furniture, originally opened in 1899, and the Attic Gallery, owned by Lesley Silver. A group of three to four lay people lead weekly Friday night services on a rotating basis, which draw a small crowd of local Jews as well as several non-Jewish supporters.