Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Waco, Texas

Waco: Historical Overview

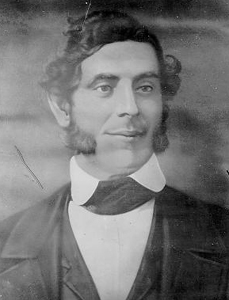

Jews have been an integral part of Waco’s development from the original founding of the city. Jacob De Cordova, the son of Sephardic Jewish parents, settled in Texas soon after it won its independence from Mexico. He acquired a large amount of land in the budding republic, and traveled around the United States trying to attract new settlers to Texas. Beginning in 1848, De Cordova laid out a new town along the Brazos River that used to be the home of the Waco Indian tribe. Along with his business partners, he divided the land into plots and sold them to prospective settlers. De Cordova guaranteed the success of this venture when he offered to set aside free land for schools, churches, and a courthouse, which led to the state’s government naming Waco Village the seat of the newly incorporated McLennan County in 1850. Six years later, the village was officially incorporated as Waco. Although he never lived in the town which he helped to establish, De Cordova laid the groundwork for Waco’s rise as a commercial center in the heart of Texas.

Like Texas itself, Waco straddles the South and West. Founded amongst prime cotton growing land, Waco had a significant slave population before the Civil War. After the war, the arrival of the railroad in 1871 turned Waco into a major inland cotton market. Cotton-related industries sprung up in town in the late 19th century, including several cotton mills. In 1868, a spur of the Chisolm Cattle Trail was built into Waco, as the town took on the feel of the Wild West. Within three years, over 600,000 head of cattle had tromped through Waco’s streets on their way north. During the 1870s, saloons and gambling houses proliferated in the frontier town, which gained the nickname “Six Shooter Junction.” Prostitution was legal and regulated in Waco until the early 20th century. With both cotton and cattle shaping the city’s economy, Waco’s culture was a mixture of South and West.

Like Texas itself, Waco straddles the South and West. Founded amongst prime cotton growing land, Waco had a significant slave population before the Civil War. After the war, the arrival of the railroad in 1871 turned Waco into a major inland cotton market. Cotton-related industries sprung up in town in the late 19th century, including several cotton mills. In 1868, a spur of the Chisolm Cattle Trail was built into Waco, as the town took on the feel of the Wild West. Within three years, over 600,000 head of cattle had tromped through Waco’s streets on their way north. During the 1870s, saloons and gambling houses proliferated in the frontier town, which gained the nickname “Six Shooter Junction.” Prostitution was legal and regulated in Waco until the early 20th century. With both cotton and cattle shaping the city’s economy, Waco’s culture was a mixture of South and West.

Stories of the Jewish Community in Waco

Jacob De Cordova

Jacob De Cordova

Early Settlers

Waco’s Jewish community developed quickly along with the local economy. Jews first arrived in the years just after the Civil War; already by 1870, Waco had a significant Jewish population, which would only grow after the town was linked by the railroad. Jews were drawn to Waco’s burgeoning business opportunities, and most opened up retail stores catering to the farmers and cowboys who came to town. Brothers Bernhard and Alex Alexander arrived from Prussia, opening a dry goods store by 1870. Polish-born Moses Goldstein came to Waco in 1868 with his wife Amanda and their six children, opening a dry goods store. Goldstein also served as a chazzan and shochet for the growing Jewish community.

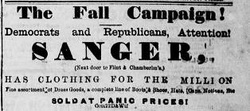

Wherever the Houston and Texas Central Railroad went, a Sanger was sure to follow. Once the track was built through Waco in 1873, Sam Sanger, a brother of the noted Texas retailing family, arrived from Philadelphia to open a branch of the Sanger Brothers dry goods store. Sanger’s store and his wholesale business were very successful and Sam became one of Waco’s leading businessmen. By 1900, the Sanger family had five servants living with them. Sam served on the board of the Waco Cotton Palace, an annual fair and exposition celebrating the city’s primary cash crop. Sam’s son Charles opened a cotton business but later joined the Sanger Brothers operation.

The railroad also brought Benjamin Haber, who had lived in several places in Texas since his arrival from Germany in 1856. He came to Waco in 1876, where he set down roots, opening a retail store. Both he and his wife Esther were very active in the Waco Jewish community. Russian-born J.A. Solomon came to Waco in the 1870s, opening a very successful dry goods store.

These Jewish merchants often had to adjust their religious practices to fit American customs and law. According to an account in the Brenham Weekly Banner newspaper in 1879, one unnamed Jewish owner of the Palace Saloon in Waco decided to close his business on the Jewish Sabbath and open it on Sunday, in violation of local blue laws. The saloon owner saw this as a test case, arguing that observing his own religion’s Sabbath should be sufficient. When other local saloon owners complained after he made $350 one Sunday, the man was charged with violating local blue laws and fined. Soon after, the Palace Saloon went back to being closed on Sundays. Indeed, Jewish merchants were unable to survive economically if they closed on Saturdays, forcing them to alter their religious observance.

When newspaper editor Charles Wessolowsky visited Waco in 1879, he was extremely impressed with the city’s economic prospects, writing that it was “destined to become a large and extensive commercial city.” It was these same prospects that attracted Jews to Waco in growing numbers in the late 19th century. Wessolowsky found about 30 Jewish families, claiming that “some of them are indeed front in rank in every branch of industry and commerce.” He singled out Solomon & Co. as having a large store that was equal to any in the country in terms of style and elegance. The Jewish community of Waco grew along with the city itself, which saw its population increase from 3,000 people in 1870 to over 20,000 by 1900.

Waco’s Jewish community developed quickly along with the local economy. Jews first arrived in the years just after the Civil War; already by 1870, Waco had a significant Jewish population, which would only grow after the town was linked by the railroad. Jews were drawn to Waco’s burgeoning business opportunities, and most opened up retail stores catering to the farmers and cowboys who came to town. Brothers Bernhard and Alex Alexander arrived from Prussia, opening a dry goods store by 1870. Polish-born Moses Goldstein came to Waco in 1868 with his wife Amanda and their six children, opening a dry goods store. Goldstein also served as a chazzan and shochet for the growing Jewish community.

Wherever the Houston and Texas Central Railroad went, a Sanger was sure to follow. Once the track was built through Waco in 1873, Sam Sanger, a brother of the noted Texas retailing family, arrived from Philadelphia to open a branch of the Sanger Brothers dry goods store. Sanger’s store and his wholesale business were very successful and Sam became one of Waco’s leading businessmen. By 1900, the Sanger family had five servants living with them. Sam served on the board of the Waco Cotton Palace, an annual fair and exposition celebrating the city’s primary cash crop. Sam’s son Charles opened a cotton business but later joined the Sanger Brothers operation.

The railroad also brought Benjamin Haber, who had lived in several places in Texas since his arrival from Germany in 1856. He came to Waco in 1876, where he set down roots, opening a retail store. Both he and his wife Esther were very active in the Waco Jewish community. Russian-born J.A. Solomon came to Waco in the 1870s, opening a very successful dry goods store.

These Jewish merchants often had to adjust their religious practices to fit American customs and law. According to an account in the Brenham Weekly Banner newspaper in 1879, one unnamed Jewish owner of the Palace Saloon in Waco decided to close his business on the Jewish Sabbath and open it on Sunday, in violation of local blue laws. The saloon owner saw this as a test case, arguing that observing his own religion’s Sabbath should be sufficient. When other local saloon owners complained after he made $350 one Sunday, the man was charged with violating local blue laws and fined. Soon after, the Palace Saloon went back to being closed on Sundays. Indeed, Jewish merchants were unable to survive economically if they closed on Saturdays, forcing them to alter their religious observance.

When newspaper editor Charles Wessolowsky visited Waco in 1879, he was extremely impressed with the city’s economic prospects, writing that it was “destined to become a large and extensive commercial city.” It was these same prospects that attracted Jews to Waco in growing numbers in the late 19th century. Wessolowsky found about 30 Jewish families, claiming that “some of them are indeed front in rank in every branch of industry and commerce.” He singled out Solomon & Co. as having a large store that was equal to any in the country in terms of style and elegance. The Jewish community of Waco grew along with the city itself, which saw its population increase from 3,000 people in 1870 to over 20,000 by 1900.

1874 Sanger store ad

1874 Sanger store ad

Organized Jewish Life in Waco

The growing numbers of Jews in Waco soon began to organize religious institutions. In 1869, 20 Jews founded the Hebrew Benevolent Association, whose primary purpose was to bury the Jewish dead and care for the sick and needy. Most of these founders were young; of the 13 who could be found in the 1870 census, all but one was under 40 years old. All were immigrants, with most coming from Prussia and Poland. A majority owned dry goods stores, while a few worked as store clerks. Soon after forming, the Benevolent Association bought land for a Jewish cemetery. They also held lavish Purim Balls each year that raised money for the society. By 1874, the local newspaper noted that the Jewish community was “famed for the magnificence of its balls.”

Although founded as a burial and charity society, the Hebrew Benevolent Association soon began holding religious services in a rented room, often led by Moses Goldstein. Jews from small towns in the area would come to town for the High Holidays. By 1869, the local newspaper noted that the town’s Jewish-owned stores would be closed for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. In 1878, the Hebrew Benevolent Association held High Holiday services in the county courthouse using a Torah the group had purchased. Members still observed traditional practices, celebrating Rosh Hashanah for two days and keeping kosher. Yet they sought to reach out to the local Gentile community, inviting the general public to observe these High Holiday services.

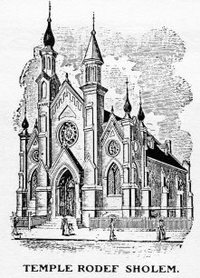

In 1873, 36 Waco Jews founded a B’nai B’rith Lodge. It was from this lodge that the push came to establish a permanent congregation. Finally, in 1879, members of the lodge organized Congregation Rodeph Sholom with Sam Sanger as their president. The Hebrew Benevolent Association gave its Torah to the fledgling group, which quickly began raising money for a synagogue. Solomon Lyons led the fundraising effort, soliciting donations from local Gentiles as well as Jews in Northern cities.

The growing numbers of Jews in Waco soon began to organize religious institutions. In 1869, 20 Jews founded the Hebrew Benevolent Association, whose primary purpose was to bury the Jewish dead and care for the sick and needy. Most of these founders were young; of the 13 who could be found in the 1870 census, all but one was under 40 years old. All were immigrants, with most coming from Prussia and Poland. A majority owned dry goods stores, while a few worked as store clerks. Soon after forming, the Benevolent Association bought land for a Jewish cemetery. They also held lavish Purim Balls each year that raised money for the society. By 1874, the local newspaper noted that the Jewish community was “famed for the magnificence of its balls.”

Although founded as a burial and charity society, the Hebrew Benevolent Association soon began holding religious services in a rented room, often led by Moses Goldstein. Jews from small towns in the area would come to town for the High Holidays. By 1869, the local newspaper noted that the town’s Jewish-owned stores would be closed for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. In 1878, the Hebrew Benevolent Association held High Holiday services in the county courthouse using a Torah the group had purchased. Members still observed traditional practices, celebrating Rosh Hashanah for two days and keeping kosher. Yet they sought to reach out to the local Gentile community, inviting the general public to observe these High Holiday services.

In 1873, 36 Waco Jews founded a B’nai B’rith Lodge. It was from this lodge that the push came to establish a permanent congregation. Finally, in 1879, members of the lodge organized Congregation Rodeph Sholom with Sam Sanger as their president. The Hebrew Benevolent Association gave its Torah to the fledgling group, which quickly began raising money for a synagogue. Solomon Lyons led the fundraising effort, soliciting donations from local Gentiles as well as Jews in Northern cities.

Jewish women in Waco established the Ladies Hebrew Aid Society in 1879 “for the purpose of assisting in the erection of a House of Worship and establishing a Sunday School.” The society held several dances to raise money for the building fund, and were able to pay for all of the synagogue’s interior furnishings. In 1881, Rodeph Sholom dedicated its synagogue on Washington Street; Rabbi Jacob Voorsanger of Beth Israel in Houston gave the dedication address. According to a local history published in 1909, when the synagogue was completed, it “was then considered the prettiest religious edifice in Waco.” Byzantine in style, with multiple spires and minarets, Rodeph Shalom’s temple reflected the growing prominence of Jews in Waco.

Rodeph Sholom hired a Rabbi May as their first spiritual leader, but he left shortly after arriving due to health problems. Next, Rabbi Aaron Suhler led the congregation for a few years before he left the rabbinate, though he remained in Waco as a member of Rodeph Sholom. Initially, the congregation did not affiliate with the Reform movement, though they did move away from strict Orthodoxy. In 1890, the congregation advertised for a rabbi who could lead services from the more conservative Minhag Jastrow prayer book and could give sermons in English. Not until 1907 did Rodeph Sholom formally affiliate with the Reform movement, joining the Union of American Hebrew Congregations.

Rodeph Sholom hired a Rabbi May as their first spiritual leader, but he left shortly after arriving due to health problems. Next, Rabbi Aaron Suhler led the congregation for a few years before he left the rabbinate, though he remained in Waco as a member of Rodeph Sholom. Initially, the congregation did not affiliate with the Reform movement, though they did move away from strict Orthodoxy. In 1890, the congregation advertised for a rabbi who could lead services from the more conservative Minhag Jastrow prayer book and could give sermons in English. Not until 1907 did Rodeph Sholom formally affiliate with the Reform movement, joining the Union of American Hebrew Congregations.

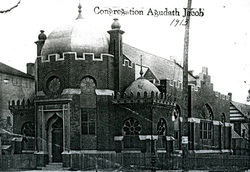

Agudath Jacob's synagogue in 1913,

Agudath Jacob's synagogue in 1913, before it was destroyed by a storm.

Photo courtesy of the Texas Collection,

Baylor University

Even though Rodeph Sholom had not fully embraced Reform, the growing number of newly arrived immigrants from Eastern Europe decided not to join Waco’s first Jewish congregation. This group of Orthodox Jews began to meet together in a room above a grocery store in 1886. Two years later, 15 men, led by A.L. Lipshitz, established Agudath Jacob, the city’s first Orthodox congregation. They initially met in a rented house which they converted into a synagogue. In 1893, they moved to a house on Columbus Street which they used as both a synagogue and Talmud Torah. In 1904, they moved the house aside and built a brick synagogue in its place; they kept the old house, using it as a school building. After a storm destroyed the synagogue, they quickly rebuilt it on the same location in 1914.

Soon after forming, Agudath Jacob hired Sam Levy to serve as chazzan, shochet, and mohel. Although he was not a rabbi, Levy played a central role in the congregation for over 50 years. He also butchered kosher chickens for members of Rodeph Sholom, which showed that the city’s oldest Jewish congregation still had traditional members. In 1902, the women of Agudath Jacob founded a Ladies Aid Society, which raised money to support both local and national Jewish causes. Pauline Fred led the society for 30 years as president.

Soon after forming, Agudath Jacob hired Sam Levy to serve as chazzan, shochet, and mohel. Although he was not a rabbi, Levy played a central role in the congregation for over 50 years. He also butchered kosher chickens for members of Rodeph Sholom, which showed that the city’s oldest Jewish congregation still had traditional members. In 1902, the women of Agudath Jacob founded a Ladies Aid Society, which raised money to support both local and national Jewish causes. Pauline Fred led the society for 30 years as president.

Rodeph Sholom's second temple, built in 1910

Rodeph Sholom's second temple, built in 1910

According to the American Jewish Year Book, by 1907 600 Jews lived in Waco. Rodeph Sholom had 56 members and $2155 in annual dues income. Agudath Jacob was smaller and poorer, with 45 members and only $1000 in income. Both congregations had religious schools. Agudath Jacob’s school was held each weekday and had 30 students, while Rodeph Sholom’s 50 students received instruction once a week. Both congregations grew over the next decade, with Agudath Israel numbering 75 members in 1919 while Rodeph Sholom had 100 members.

After having a series of short-tenured rabbis, both Rodeph Sholom and Agudath Jacob eventually hired spiritual leaders who had a significant impact on their congregations. Rabbi Isadore Warsaw came to Rodeph Sholom in 1908, and soon began to push for a new synagogue, arguing that their 27 year-old building was inadequate to hold the growing congregation and its religious school. With Rabbi Warsaw’s influence, the congregation decided to build a new, larger temple on the same site as their old one, laying the cornerstone for the new structure in 1909. Completed in 1910, Rodeph Sholom’s new home could seat 400 in its sanctuary. Rabbi Warsaw left Waco in 1918 and was replaced by Wolfe Macht, who led Rodeph Sholom for the next 33 years.

Agudath Jacob also outgrew its old facilities. In 1923, the congregation tore down the old house it had been using as an education building, and replaced it with a new Hebrew Institute that had additional classrooms as well as a banquet hall, kitchen, and gymnasium. Agudath Jacob even sponsored its own youth basketball team that used the new gym. The congregation also added a mikvah (ritual bath), which reflected the congregation’s continued observance of Orthodox practice. In 1924, Agudath Jacob hired Rabbi Charles Blumenthal, who led the congregation until 1945.

After having a series of short-tenured rabbis, both Rodeph Sholom and Agudath Jacob eventually hired spiritual leaders who had a significant impact on their congregations. Rabbi Isadore Warsaw came to Rodeph Sholom in 1908, and soon began to push for a new synagogue, arguing that their 27 year-old building was inadequate to hold the growing congregation and its religious school. With Rabbi Warsaw’s influence, the congregation decided to build a new, larger temple on the same site as their old one, laying the cornerstone for the new structure in 1909. Completed in 1910, Rodeph Sholom’s new home could seat 400 in its sanctuary. Rabbi Warsaw left Waco in 1918 and was replaced by Wolfe Macht, who led Rodeph Sholom for the next 33 years.

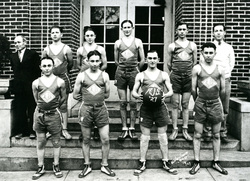

Agudath Jacob also outgrew its old facilities. In 1923, the congregation tore down the old house it had been using as an education building, and replaced it with a new Hebrew Institute that had additional classrooms as well as a banquet hall, kitchen, and gymnasium. Agudath Jacob even sponsored its own youth basketball team that used the new gym. The congregation also added a mikvah (ritual bath), which reflected the congregation’s continued observance of Orthodox practice. In 1924, Agudath Jacob hired Rabbi Charles Blumenthal, who led the congregation until 1945.

Agudath Jacob's basketball team in 1927. Photo courtesy of the Texas Collection, Baylor University.

Agudath Jacob's basketball team in 1927. Photo courtesy of the Texas Collection, Baylor University.

Jewish Organizations in Waco

Waco Jews established several other organizations that pursued a range of goals. In 1882, they established a Russian Refugee Society, headed by Sam Sanger, that helped settle Jewish immigrants fleeing Czarist oppression. Although this group was short-lived, Waco Jews would continue to help settle Jewish immigrants through the work of the Industrial Removal Office and the Galveston Immigration Movement in the early 20th century. In 1887, Jews in Waco founded the Young Men’s Hebrew Association which offered both educational and social programs. The group soon evolved into a purely social organization, changing its name to the Progress Club in 1900 and acquiring a clubhouse that contained a ballroom, dining room, billiard room, and the only roof garden in the city. The social club had 42 members in 1907, most all of whom were affiliated with Rodeph Sholom. Later, another YMHA was established by 1919.

In 1898, members of Agudath Jacob founded the Ezrath Zion Society, which served as both a free loan society and a Zionist organization. The group would lend money at no interest to newly arrived Jewish immigrants to help them get started in a business. In 1913, the group split its functions, creating a new free loan society called G’miluth Chasodim while Ezrath Zion continued to work toward the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine. By 1919, Ezrath Zion had 102 members, while the Daughters of Zion, a women’s group, had 50 members. Both of these Zionist groups were closely affiliated with Agudath Jacob with most of their members being first generation immigrants. In 1927, Jewish women in Waco founded a chapter of Hadassah.

These recent immigrants from Eastern Europe also established a branch of the socialist Workmen’s Circle in 1912. Kalman Solovey, a Latvian immigrant who owned a grocery store, and F. Israel were the founders of the group. The Workmen’s Circle brought Yiddish programs to Waco for many years, while also raising money to help Jewish refugees during World War I and other Jewish causes. In 1931, a Ladies Auxiliary of the circle was established, which focused primarily on charity work.

Waco Jews established several other organizations that pursued a range of goals. In 1882, they established a Russian Refugee Society, headed by Sam Sanger, that helped settle Jewish immigrants fleeing Czarist oppression. Although this group was short-lived, Waco Jews would continue to help settle Jewish immigrants through the work of the Industrial Removal Office and the Galveston Immigration Movement in the early 20th century. In 1887, Jews in Waco founded the Young Men’s Hebrew Association which offered both educational and social programs. The group soon evolved into a purely social organization, changing its name to the Progress Club in 1900 and acquiring a clubhouse that contained a ballroom, dining room, billiard room, and the only roof garden in the city. The social club had 42 members in 1907, most all of whom were affiliated with Rodeph Sholom. Later, another YMHA was established by 1919.

In 1898, members of Agudath Jacob founded the Ezrath Zion Society, which served as both a free loan society and a Zionist organization. The group would lend money at no interest to newly arrived Jewish immigrants to help them get started in a business. In 1913, the group split its functions, creating a new free loan society called G’miluth Chasodim while Ezrath Zion continued to work toward the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine. By 1919, Ezrath Zion had 102 members, while the Daughters of Zion, a women’s group, had 50 members. Both of these Zionist groups were closely affiliated with Agudath Jacob with most of their members being first generation immigrants. In 1927, Jewish women in Waco founded a chapter of Hadassah.

These recent immigrants from Eastern Europe also established a branch of the socialist Workmen’s Circle in 1912. Kalman Solovey, a Latvian immigrant who owned a grocery store, and F. Israel were the founders of the group. The Workmen’s Circle brought Yiddish programs to Waco for many years, while also raising money to help Jewish refugees during World War I and other Jewish causes. In 1931, a Ladies Auxiliary of the circle was established, which focused primarily on charity work.

Zionist & American flags on display during event at Agudath Jacobs c. 1910.

Zionist & American flags on display during event at Agudath Jacobs c. 1910. Photo courtesy of the Texas Collection, Baylor University.

Indeed charity had long been a focus of the Waco Jewish community. The Hebrew Benevolent Association remained active into the 20th century, drawing significant support from members of both congregations. In 1927, Waco Jews founded the Jewish Federated Charities, which consolidated the various Jewish charity efforts in town. Later the organization changed its name to the Jewish Welfare Council, and in 1984 it became the Jewish Federation of Waco and Central Texas, raising money for local, national, and international Jewish causes.

Waco Jews did not restrict their charity to the Jewish community, often giving money to church building funds. According to a report in the American Israelite newspaper around the turn of the century, “there is not a Christian church in the city or county” which Waco Jews did not help support financially. In 1913, Jewish women in Waco, led by Carrie Sanger Godshaw, founded a local chapter of the Council of Jewish Women. The CJW opened a night school for newly arrived immigrants to help them learn English and started a penny lunch program at a local school. They also had a program to give socks and shoes to needy children. Godshaw was involved in a number of progressive causes in Waco. An activist for women’s suffrage, she founded the local chapter of the League of Women Voters. She also established the city’s first Montessori kindergarten in 1916 and served as a director of Planned Parenthood.

Waco Jews did not restrict their charity to the Jewish community, often giving money to church building funds. According to a report in the American Israelite newspaper around the turn of the century, “there is not a Christian church in the city or county” which Waco Jews did not help support financially. In 1913, Jewish women in Waco, led by Carrie Sanger Godshaw, founded a local chapter of the Council of Jewish Women. The CJW opened a night school for newly arrived immigrants to help them learn English and started a penny lunch program at a local school. They also had a program to give socks and shoes to needy children. Godshaw was involved in a number of progressive causes in Waco. An activist for women’s suffrage, she founded the local chapter of the League of Women Voters. She also established the city’s first Montessori kindergarten in 1916 and served as a director of Planned Parenthood.

The Goldstein-Migel annex.

The Goldstein-Migel annex. Photo courtesy of UT-Arlington.

Goldstein and Migel

As in other Southern cities, Waco Jews were heavily concentrated in business, especially retail trade. Jews owned a wide array of businesses in the early 20th century, including stores selling jewelry, clothing, dry goods, and furniture. Perhaps the best known was the Goldstein & Migel Department Store. Isaac Goldstein moved to Waco as a boy in 1868 with his father Moses. In 1888, he opened a dry goods store with his brother-in-law Louey Migel, who had been born in Russia. Their business eventually grew into the city’s largest and best department store.

Both Goldstein and Migel became leading figures in Waco civic life. Goldstein was a strong supporter of public libraries, even putting a circulating library in his department store during its early years. He led the effort to build a public library in Waco, donating land and raising money to match a grant from the Carnegie Fund. Goldstein spent 19 years as president of the Waco Public Library. Goldstein also served many years on the board of the First National Bank of Waco. Migel spent 25 years as president of Rodeph Sholom and donated land for the Waco Boys Club. According to one local history published in 1902, Migel’s “name is almost a household word” in Waco due to his civic involvement. Aaron Goldstein later took over the department store and followed in his served as a civic leader. Aaron served several terms as a city commissioner and was president of the Waco Chamber of Commerce.

As in other Southern cities, Waco Jews were heavily concentrated in business, especially retail trade. Jews owned a wide array of businesses in the early 20th century, including stores selling jewelry, clothing, dry goods, and furniture. Perhaps the best known was the Goldstein & Migel Department Store. Isaac Goldstein moved to Waco as a boy in 1868 with his father Moses. In 1888, he opened a dry goods store with his brother-in-law Louey Migel, who had been born in Russia. Their business eventually grew into the city’s largest and best department store.

Both Goldstein and Migel became leading figures in Waco civic life. Goldstein was a strong supporter of public libraries, even putting a circulating library in his department store during its early years. He led the effort to build a public library in Waco, donating land and raising money to match a grant from the Carnegie Fund. Goldstein spent 19 years as president of the Waco Public Library. Goldstein also served many years on the board of the First National Bank of Waco. Migel spent 25 years as president of Rodeph Sholom and donated land for the Waco Boys Club. According to one local history published in 1902, Migel’s “name is almost a household word” in Waco due to his civic involvement. Aaron Goldstein later took over the department store and followed in his served as a civic leader. Aaron served several terms as a city commissioner and was president of the Waco Chamber of Commerce.

Gussie Oscar. Photo courtesy of

Gussie Oscar. Photo courtesy of the Texas Collection, Baylor University.

Gussie Oscar

In a description of Waco’s Jewish community written in 1909, Isaac Goldstein explained that while Jews had not been very involved in local politics, “in enterprise for the upbuilding of our city and in public undertakings they are among the foremost.” One of the most colorful and controversial figures in Waco was Gussie Oscar, who moved to town from Calvert in 1905 to play in the orchestra of the Majestic Theater. By 1911, Oscar conducted an all-female orchestra and later toured the country as a piano player for singer May Irwin. When Oscar returned to Texas, she became the manager of the Waco Auditorium, often challenging local laws and social mores with her programs.

Never married, Oscar lived by herself in the honeymoon suite of a local hotel. She challenged local blue laws by showing movies on Sundays. In 1917, she brought in a lecturer on birth control, who spoke to single-sex audiences; the lecturer spoke to women during the day and men during the evening. Oscar also brought in big name stars like Will Rogers, Harry Houdini, and the Marx Brothers to Waco. During the roaring 1920s, Oscar began to bring in risqué plays containing sexual innuendo. One of these plays, Irving Berlin’s, Music Box Review, led to the arrest of 20 actresses and Oscar herself for indecency. This crackdown led to the closing of the theater as traveling acts would no longer come to Waco. Despite this setback, Oscar remained in show business, booking events at other theaters in Waco and in other towns in the area until her death in 1950.

In a description of Waco’s Jewish community written in 1909, Isaac Goldstein explained that while Jews had not been very involved in local politics, “in enterprise for the upbuilding of our city and in public undertakings they are among the foremost.” One of the most colorful and controversial figures in Waco was Gussie Oscar, who moved to town from Calvert in 1905 to play in the orchestra of the Majestic Theater. By 1911, Oscar conducted an all-female orchestra and later toured the country as a piano player for singer May Irwin. When Oscar returned to Texas, she became the manager of the Waco Auditorium, often challenging local laws and social mores with her programs.

Never married, Oscar lived by herself in the honeymoon suite of a local hotel. She challenged local blue laws by showing movies on Sundays. In 1917, she brought in a lecturer on birth control, who spoke to single-sex audiences; the lecturer spoke to women during the day and men during the evening. Oscar also brought in big name stars like Will Rogers, Harry Houdini, and the Marx Brothers to Waco. During the roaring 1920s, Oscar began to bring in risqué plays containing sexual innuendo. One of these plays, Irving Berlin’s, Music Box Review, led to the arrest of 20 actresses and Oscar herself for indecency. This crackdown led to the closing of the theater as traveling acts would no longer come to Waco. Despite this setback, Oscar remained in show business, booking events at other theaters in Waco and in other towns in the area until her death in 1950.

Rodeph Sholom's current temple,

Rodeph Sholom's current temple, built in 1961.

Photo courtesy of Julian Preisler

The 20th Century

Waco grew tremendously over the 20th century, greatly aided by the military buildup during the world wars. During World War I, the army built Camp McArthur just outside the city; over 35,000 soldiers were stationed there during the war, matching Waco’s pre-war population. Business boomed in the city during the war and its aftermath. During the Great Depression, Waco suffered as the local cotton industry was decimated. As with the rest of the country, World War II rescued the city financially. Numerous war industry factories were built in addition to several military installations in the area. Connally Air Force Base remained open after the war, as Waco’s population reached 84,000 by 1952. Its Jewish community grew as well, but only slightly, from 1,150 people in 1937 to 1,250 in 1960.

Waco’s downtown was leveled by a catastrophic tornado in 1953, which destroyed almost 600 business buildings in the city and killed 114 people, including two Jews. After the tornado, many businesses relocated to new suburban shopping centers as the downtown district went into decline. In 1966, in another economic blow to the city. Connally Air Force Base closed. Waco’s general population began to decline in the 1960s. At the same time, the Jewish community began to shrink steadily as well. By 1980, only 750 Jews lived in Waco. In 1997, this number was down to an estimated 300 people.

Despite this decline, both of Waco’s congregations persevered. Agudath Jacob moved to a new synagogue in 1951, where it remained for the next 21 years. In 1966, the congregation reached its peak of 183 member families; that same year, Agudath Jacob decided to move away from Orthodoxy, affiliating with the Conservative movement. When Agudath Jacob dedicated its new synagogue on Hillcrest Drive in 1972, they were down to 153 members. Rodeph Sholom also moved to a new building in the post-war years. With the arrival of the baby boom generation, the congregation soon outgrew its old temple. When the new synagogue was dedicated on North 41st Street in 1961, Rodeph Sholom had 170 contributing members and over 100 children in its religious school. After Rabbi Macht’s retirement in 1952, the congregation hired Charles Lesser and later Amiel Wohl as their spiritual leader. In 1964, Rodeph Sholom hired Rabbi Mordecai Podet, who led the Reform congregation until his retirement in 1988. Podet was very active in the larger community, serving as chairman of the Waco Human Relations Council and president of the Waco Ministerial Alliance.

Waco grew tremendously over the 20th century, greatly aided by the military buildup during the world wars. During World War I, the army built Camp McArthur just outside the city; over 35,000 soldiers were stationed there during the war, matching Waco’s pre-war population. Business boomed in the city during the war and its aftermath. During the Great Depression, Waco suffered as the local cotton industry was decimated. As with the rest of the country, World War II rescued the city financially. Numerous war industry factories were built in addition to several military installations in the area. Connally Air Force Base remained open after the war, as Waco’s population reached 84,000 by 1952. Its Jewish community grew as well, but only slightly, from 1,150 people in 1937 to 1,250 in 1960.

Waco’s downtown was leveled by a catastrophic tornado in 1953, which destroyed almost 600 business buildings in the city and killed 114 people, including two Jews. After the tornado, many businesses relocated to new suburban shopping centers as the downtown district went into decline. In 1966, in another economic blow to the city. Connally Air Force Base closed. Waco’s general population began to decline in the 1960s. At the same time, the Jewish community began to shrink steadily as well. By 1980, only 750 Jews lived in Waco. In 1997, this number was down to an estimated 300 people.

Despite this decline, both of Waco’s congregations persevered. Agudath Jacob moved to a new synagogue in 1951, where it remained for the next 21 years. In 1966, the congregation reached its peak of 183 member families; that same year, Agudath Jacob decided to move away from Orthodoxy, affiliating with the Conservative movement. When Agudath Jacob dedicated its new synagogue on Hillcrest Drive in 1972, they were down to 153 members. Rodeph Sholom also moved to a new building in the post-war years. With the arrival of the baby boom generation, the congregation soon outgrew its old temple. When the new synagogue was dedicated on North 41st Street in 1961, Rodeph Sholom had 170 contributing members and over 100 children in its religious school. After Rabbi Macht’s retirement in 1952, the congregation hired Charles Lesser and later Amiel Wohl as their spiritual leader. In 1964, Rodeph Sholom hired Rabbi Mordecai Podet, who led the Reform congregation until his retirement in 1988. Podet was very active in the larger community, serving as chairman of the Waco Human Relations Council and president of the Waco Ministerial Alliance.

Bernard Rapoport

Bernard Rapoport

Jews continued to play a leading role in Waco’s civic affairs. During the civil rights era, city business leaders founded a committee to handle the integration of public facilities in Waco in 1961. City leaders were worried that the Air Force would close its nearby base if black soldiers were forced to use segregated facilities in the city. With this economic threat, the leaders decided that they needed to integrate. A.M. Goldstein of the Goldstein-Migel Department Store led this committee which worked quietly to integrate the city’s stores and other public places without protests or unrest. Bernard Rapoport was raised in a politically radical family in San Antonio. Although he later became a successful businessman, creating the American Income Life Insurance Company, he never forgot his progressive roots. Rapoport was actively involved in both state and national politics as a major funder of the Democratic Party. He and his wife Audre endowed several chairs at the University of Texas at Austin and other universities.

The Jewish Community in Waco Today

As of the early 21st century, Waco is a growing city, but its Jewish population continues to decline. Most of the Jewish children raised in the city have moved away to larger cities seeking greater economic and social opportunities. Rodeph Sholom, which had 161 families in 1995, had only 98 in 2011. Agudath Jacob is even smaller, with about 80 member households in 2011. Despite their small size, both congregations continue to employ full-time rabbis.