Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Birmingham, Alabama

Historical Overview

Stories of the Jewish Community in Birmingham

Beth El's

synagogue

in Bessemer

Beth El's

synagogue

in Bessemer

Early Settlers

Henry and Paula Simon left their small general store in Selma and went north to Birmingham to seek their fortunes. Samuel and Henrietta Marx, Bavarian immigrants living in Montgomery with their five children, soon followed. Issaac Hochstadter hopped on a train from Philadelphia. These young families, among others, established stores to meet the needs of the growing numbers of mine and factory workers of the Elyton Land Company. With the growth of this new merchant class and the steady expansion of industry, a full city emerged overnight, as if by magic. It was no surprise that people started referring to Birmingham as “The Magic City.”

Bent on rapid commercial growth, the city fell victim to a massive cholera epidemic only a few years after its founding. During these years few people came to Birmingham. In 1875, in an attempt to curb the epidemic, the Elyton Company almost went bankrupt when it tried to provide the city with a new source of clean water. The city that at first seemed so prosperous was already on the brink of an untimely end. Despite these unsettling times, Samuel and Henrietta Marx had two new children, Bertha and Hugo, the first Jews to be born in Birmingham. In the midst of sanitary and financial uncertainty, the Jews of Birmingham persevered and formed the first formal organization of a Jewish community.

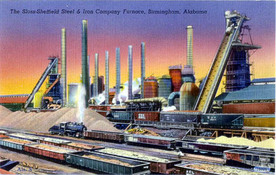

By 1878, the cholera epidemic had mostly run its course and more Jews began to relocate to Birmingham. With great excitement, Henry and Paula Simon invited the new group into their home to celebrate and pray together for the city’s first observance of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur in 1881. A year later, with thirty-two members, they met again at the Masonic Hall to sign a charter for a new organization called Temple Emanu-El. For their first public worship services, they met at the Cumberland Presbyterian Church. With new members continually joining, they soon had enough money to purchase a plot of land from the Elyton Land Company in 1884. In 1886, they laid a cornerstone for their new building on the corner of 5th Avenue and 17th Street North. By this time, Birmingham’s industrialists had capitalized on a breakthrough in iron technology and the city enjoyed a huge iron boom. Electric lights dominated its streets and its population, spurred by the blasting pig iron furnaces, jumped to 3,086. With its 85 members, Temple Emanu-El moved into their newly finished synagogue on January 24, 1889.

From Russia to the Northside

On the northern side of Red Mountain, industrial and commercial developments began a spurt of unbridled growth. But on the mostly green slopes of the other side of the mountain, Birmingham’s affluent factory owners and business leaders began to flock and establish the fashionable Southside neighborhood. Some of the Jews of Temple Emanu-El—mostly German Jews who had been in the country for several years—also began moving to these new neighborhoods away from the smoke and grit of Birmingham’s urban center. This group of Jews strove to be active citizens in the general community and to achieve the same level of affluence and respect as their Gentile neighbors. Meanwhile, on the other side of Red Mountain, in the Northside neighborhood, a different sort of Jewish community filled the streets.

During the late 19th century, a wave of Eastern European Jewish immigrants began to arrive in America, seeking economic freedom and civil liberties. In Birmingham, they clustered their homes together in the tightly packed neighborhood called the Northside. By 1888, enough had gathered in Birmingham to form an Orthodox congregation of their own. With seventy-five members, Congregation Knesseth Israel was born on July 4th of that year. In its early years, the congregation met in rented rooms and sometimes at Emanu-El to celebrate the Sabbath and the High Holidays. In 1903, Knesseth Israel built a synagogue of their own on Seventh Ave and 17th Street North.

In those days, walking around between 8th Avenue and 13th Street North, one might have thought they had stepped into a little slice of Russia or Poland. They would have heard Yiddish spoken all around them, passed Jewish bakeries and Hebrew bookstores, and seen Mrs. Pasckovitz patrolling the street with her milk cow, or Rabbi Chamovitz with his long beard and stern gaze. As newly settled American citizens, these Eastern European Jews lived in near poverty, inhabiting small modest homes with few modern amenities. Mr. and Mrs. Harris Schwartz owned and operated the neighborhood mikvah and enjoyed a profitable business because few people in the poor community owned their own bathtub.

Though many German Jews had not yet reached the social status requisite for moving to the Southside, they were ambivalent about mingling with these new Birmingham settlers. Many hoped to establish themselves as assimilated Americans, and thought the Eastern European Jews’ connection to old world traditions and language antithetical to this mission. Thus, relations between the two communities remained strained and distant for years.

Henry and Paula Simon left their small general store in Selma and went north to Birmingham to seek their fortunes. Samuel and Henrietta Marx, Bavarian immigrants living in Montgomery with their five children, soon followed. Issaac Hochstadter hopped on a train from Philadelphia. These young families, among others, established stores to meet the needs of the growing numbers of mine and factory workers of the Elyton Land Company. With the growth of this new merchant class and the steady expansion of industry, a full city emerged overnight, as if by magic. It was no surprise that people started referring to Birmingham as “The Magic City.”

Bent on rapid commercial growth, the city fell victim to a massive cholera epidemic only a few years after its founding. During these years few people came to Birmingham. In 1875, in an attempt to curb the epidemic, the Elyton Company almost went bankrupt when it tried to provide the city with a new source of clean water. The city that at first seemed so prosperous was already on the brink of an untimely end. Despite these unsettling times, Samuel and Henrietta Marx had two new children, Bertha and Hugo, the first Jews to be born in Birmingham. In the midst of sanitary and financial uncertainty, the Jews of Birmingham persevered and formed the first formal organization of a Jewish community.

By 1878, the cholera epidemic had mostly run its course and more Jews began to relocate to Birmingham. With great excitement, Henry and Paula Simon invited the new group into their home to celebrate and pray together for the city’s first observance of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur in 1881. A year later, with thirty-two members, they met again at the Masonic Hall to sign a charter for a new organization called Temple Emanu-El. For their first public worship services, they met at the Cumberland Presbyterian Church. With new members continually joining, they soon had enough money to purchase a plot of land from the Elyton Land Company in 1884. In 1886, they laid a cornerstone for their new building on the corner of 5th Avenue and 17th Street North. By this time, Birmingham’s industrialists had capitalized on a breakthrough in iron technology and the city enjoyed a huge iron boom. Electric lights dominated its streets and its population, spurred by the blasting pig iron furnaces, jumped to 3,086. With its 85 members, Temple Emanu-El moved into their newly finished synagogue on January 24, 1889.

From Russia to the Northside

On the northern side of Red Mountain, industrial and commercial developments began a spurt of unbridled growth. But on the mostly green slopes of the other side of the mountain, Birmingham’s affluent factory owners and business leaders began to flock and establish the fashionable Southside neighborhood. Some of the Jews of Temple Emanu-El—mostly German Jews who had been in the country for several years—also began moving to these new neighborhoods away from the smoke and grit of Birmingham’s urban center. This group of Jews strove to be active citizens in the general community and to achieve the same level of affluence and respect as their Gentile neighbors. Meanwhile, on the other side of Red Mountain, in the Northside neighborhood, a different sort of Jewish community filled the streets.

During the late 19th century, a wave of Eastern European Jewish immigrants began to arrive in America, seeking economic freedom and civil liberties. In Birmingham, they clustered their homes together in the tightly packed neighborhood called the Northside. By 1888, enough had gathered in Birmingham to form an Orthodox congregation of their own. With seventy-five members, Congregation Knesseth Israel was born on July 4th of that year. In its early years, the congregation met in rented rooms and sometimes at Emanu-El to celebrate the Sabbath and the High Holidays. In 1903, Knesseth Israel built a synagogue of their own on Seventh Ave and 17th Street North.

In those days, walking around between 8th Avenue and 13th Street North, one might have thought they had stepped into a little slice of Russia or Poland. They would have heard Yiddish spoken all around them, passed Jewish bakeries and Hebrew bookstores, and seen Mrs. Pasckovitz patrolling the street with her milk cow, or Rabbi Chamovitz with his long beard and stern gaze. As newly settled American citizens, these Eastern European Jews lived in near poverty, inhabiting small modest homes with few modern amenities. Mr. and Mrs. Harris Schwartz owned and operated the neighborhood mikvah and enjoyed a profitable business because few people in the poor community owned their own bathtub.

Though many German Jews had not yet reached the social status requisite for moving to the Southside, they were ambivalent about mingling with these new Birmingham settlers. Many hoped to establish themselves as assimilated Americans, and thought the Eastern European Jews’ connection to old world traditions and language antithetical to this mission. Thus, relations between the two communities remained strained and distant for years.

The Bessemer Community

Other Jewish immigrants settled in the nearby town of Bessemer, where the Bessemer Land and Improvement Company set aside land for a synagogue in 1887 even though there was no congregation yet. Not until 1889 did Bessemer’s small but growing Jewish community begin to gather together to pray. In 1892, the group formally established Congregation Beth El, and soon after, the land was legally transferred to the group. The congregation constructed a house of worship on the site in 1906. During its first few decades, the congregation had lay-led services before hiring a rabbi in 1917. The congregation had joined the Reform Union of American Hebrew Congregations by 1910, though it soon dropped it membership. Disputes over worship style briefly split the congregation when an Orthodox faction broke away and met above stores on 2nd Avenue. After five years, the two groups reunited.

Bessemer’s Jewish community was never large, peaking at 110 Jews in 1927. As a result, Beth El remained small throughout its history, though it did manage to employ Rabbi Joseph Gallinger as its spiritual leader from 1948 to 1957. During Rabbi Gallinger's tenure, the congregation enlarged the synagogue, adding a new brick exterior. The congregation disbanded in the early 1970s, due to declining membership as the Bessemer Jewish community had shrunk considerably; Bessemer’s remaining Jewish community traveled the15 miles or so to Birmingham for religious services.

Cleaning Up “Bad Birmingham”

As the city of Birmingham grew in the late 19th century, so did its population of poor miners, its cloud of smog, its murder rate, and its unsanitary living conditions. In the national media, the once Magic City had now been dubbed “Bad Birmingham.” In the 1890s, the city was also saddled with the unfortunate monikers of “murder capital of the world” and “the dirtiest city on earth.” In these years, Birmingham had an extensive red light district and a wide variety of saloons and houses of ill repute. While the industrialists and merchant class rode the iron boom to wealth and comfort, the city’s working class became increasingly impoverished, living in squalor. Although the Panic of 1893 brought the entire city to economic hard times, it brought about especially dire conditions for the miners and incited a massive strike in that same year.

In the unpleasant climate of the "Bad Birmingham" years, Temple Emanu-El also faced challenges. Between 1890 and 1894, the congregation had a difficult time maintaining its membership numbers and meeting its budget. They also dealt with internal divisions within their community. In 1889, Rabbi Maurice Eisenberg came to serve Temple Emanu-El as its spiritual leader. Many in the congregation found him to be far too traditional for their Reform congregation, which had joined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations the previous year. Several congregants angrily left Emanu-El to form the short-lived, independent Congregation B’nai Israel in 1890.

Despite these setbacks and tough times in the city, many of Temple Emanu-El’s members continued to prosper as they had earlier. In fact, as they rose to prominent positions in the city’s life, members of the Jewish community played instrumental roles in fighting to relieve many of Birmingham’s urban woes. While many in the city made bold efforts to curb the troubling persistence of poverty, several in the Jewish community proudly took up that mission.

Other Jewish immigrants settled in the nearby town of Bessemer, where the Bessemer Land and Improvement Company set aside land for a synagogue in 1887 even though there was no congregation yet. Not until 1889 did Bessemer’s small but growing Jewish community begin to gather together to pray. In 1892, the group formally established Congregation Beth El, and soon after, the land was legally transferred to the group. The congregation constructed a house of worship on the site in 1906. During its first few decades, the congregation had lay-led services before hiring a rabbi in 1917. The congregation had joined the Reform Union of American Hebrew Congregations by 1910, though it soon dropped it membership. Disputes over worship style briefly split the congregation when an Orthodox faction broke away and met above stores on 2nd Avenue. After five years, the two groups reunited.

Bessemer’s Jewish community was never large, peaking at 110 Jews in 1927. As a result, Beth El remained small throughout its history, though it did manage to employ Rabbi Joseph Gallinger as its spiritual leader from 1948 to 1957. During Rabbi Gallinger's tenure, the congregation enlarged the synagogue, adding a new brick exterior. The congregation disbanded in the early 1970s, due to declining membership as the Bessemer Jewish community had shrunk considerably; Bessemer’s remaining Jewish community traveled the15 miles or so to Birmingham for religious services.

Cleaning Up “Bad Birmingham”

As the city of Birmingham grew in the late 19th century, so did its population of poor miners, its cloud of smog, its murder rate, and its unsanitary living conditions. In the national media, the once Magic City had now been dubbed “Bad Birmingham.” In the 1890s, the city was also saddled with the unfortunate monikers of “murder capital of the world” and “the dirtiest city on earth.” In these years, Birmingham had an extensive red light district and a wide variety of saloons and houses of ill repute. While the industrialists and merchant class rode the iron boom to wealth and comfort, the city’s working class became increasingly impoverished, living in squalor. Although the Panic of 1893 brought the entire city to economic hard times, it brought about especially dire conditions for the miners and incited a massive strike in that same year.

In the unpleasant climate of the "Bad Birmingham" years, Temple Emanu-El also faced challenges. Between 1890 and 1894, the congregation had a difficult time maintaining its membership numbers and meeting its budget. They also dealt with internal divisions within their community. In 1889, Rabbi Maurice Eisenberg came to serve Temple Emanu-El as its spiritual leader. Many in the congregation found him to be far too traditional for their Reform congregation, which had joined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations the previous year. Several congregants angrily left Emanu-El to form the short-lived, independent Congregation B’nai Israel in 1890.

Despite these setbacks and tough times in the city, many of Temple Emanu-El’s members continued to prosper as they had earlier. In fact, as they rose to prominent positions in the city’s life, members of the Jewish community played instrumental roles in fighting to relieve many of Birmingham’s urban woes. While many in the city made bold efforts to curb the troubling persistence of poverty, several in the Jewish community proudly took up that mission.

The Ullman Family

Though many Jews took active roles in the community and provided their energy to charitable organizations and reform movements, few stand out like Samuel Ullman. He and his wife Emma came from Natchez, Mississippi in 1884 to open a hardware store. He almost immediately became president of Temple Emanu-El’s board of trustees. When he took over as lay leader in 1892, the breakaway Congregation B’nai Israel approved of his leadership and reunited with Emanu-El. By joining the Birmingham Board of Education the same year he arrived, Ullman cemented his important role in the history of the city. In board meetings, he would often arouse criticism due to his outspoken support of various controversial proposals. In 1899, Ullman persuaded the city to build its first permanent public high school. After years of negotiations, Central High School opened its doors in 1906.

The education of all of Birmingham’s young people deeply concerned Ullman. He actively lobbied for the adequate education of Birmingham’s black community. Though he advocated mostly segregated vocational schooling for black youths, such support was progressive for its time. In 1900, after Ullman’s constant prodding of the Board of Education, the Industrial High School began its first day of classes with eighteen African American students. In ten years, its numbers grew to 200. It was later renamed the Ullman School in honor of Ullman’s contributions.

Emma Ullman also contributed to the lives of Birmingham’s mostly impoverished population. Her ties to the philanthropic community allowed her to help initiate the Hospital of United Charities. It was the first in the region to serve indigent and black patients; when the state took it over in 1907, she stipulated that it continue to serve these populations.

The Steiner Plan

As a young city almost completely dependent on one industry, Birmingham suffered a serious economic setback in the Panic of 1893. With diminishing tax revenue, the city had little money to pay interest on its bonds. The economic crisis almost brought Birmingham to its knees. However, due to the ingenuity of two Jewish bankers and their so-called “Steiner Plan,” the city government survived. Burghard and Sigfried Steiner immigrated from Austria in the 1870s and settled originally in Uniontown, Alabama, where they worked as post masters, business proprietors, and railroad agents. In 1887, the Steiner Brothers came to Birmingham to open a bank. In 1890, with the construction of a new impressive bank building on 1st Avenue they had squarely established themselves as central figures in the Birmingham financial community. Three years later their innovation proved to be the city’s salvation.

“The Steiner Plan” proposed to have the city’s interest on municipal bonds underwritten by the bank and then deferred for five years. Sigfried personally visited bond holders and explained the plan, and bought back the bonds of those who had doubts about the city’s ability to return the interest. The plan was a success, and the city was eventually able to pay its interest. Other cities in financial trouble have adopted similar plans based on the Steiners’ model.

Though many Jews took active roles in the community and provided their energy to charitable organizations and reform movements, few stand out like Samuel Ullman. He and his wife Emma came from Natchez, Mississippi in 1884 to open a hardware store. He almost immediately became president of Temple Emanu-El’s board of trustees. When he took over as lay leader in 1892, the breakaway Congregation B’nai Israel approved of his leadership and reunited with Emanu-El. By joining the Birmingham Board of Education the same year he arrived, Ullman cemented his important role in the history of the city. In board meetings, he would often arouse criticism due to his outspoken support of various controversial proposals. In 1899, Ullman persuaded the city to build its first permanent public high school. After years of negotiations, Central High School opened its doors in 1906.

The education of all of Birmingham’s young people deeply concerned Ullman. He actively lobbied for the adequate education of Birmingham’s black community. Though he advocated mostly segregated vocational schooling for black youths, such support was progressive for its time. In 1900, after Ullman’s constant prodding of the Board of Education, the Industrial High School began its first day of classes with eighteen African American students. In ten years, its numbers grew to 200. It was later renamed the Ullman School in honor of Ullman’s contributions.

Emma Ullman also contributed to the lives of Birmingham’s mostly impoverished population. Her ties to the philanthropic community allowed her to help initiate the Hospital of United Charities. It was the first in the region to serve indigent and black patients; when the state took it over in 1907, she stipulated that it continue to serve these populations.

The Steiner Plan

As a young city almost completely dependent on one industry, Birmingham suffered a serious economic setback in the Panic of 1893. With diminishing tax revenue, the city had little money to pay interest on its bonds. The economic crisis almost brought Birmingham to its knees. However, due to the ingenuity of two Jewish bankers and their so-called “Steiner Plan,” the city government survived. Burghard and Sigfried Steiner immigrated from Austria in the 1870s and settled originally in Uniontown, Alabama, where they worked as post masters, business proprietors, and railroad agents. In 1887, the Steiner Brothers came to Birmingham to open a bank. In 1890, with the construction of a new impressive bank building on 1st Avenue they had squarely established themselves as central figures in the Birmingham financial community. Three years later their innovation proved to be the city’s salvation.

“The Steiner Plan” proposed to have the city’s interest on municipal bonds underwritten by the bank and then deferred for five years. Sigfried personally visited bond holders and explained the plan, and bought back the bonds of those who had doubts about the city’s ability to return the interest. The plan was a success, and the city was eventually able to pay its interest. Other cities in financial trouble have adopted similar plans based on the Steiners’ model.

Rabbi Morris Newfield

Another important reformer was Rabbi Morris Newfield of Temple Emanu-El, who was beloved both within and without his religious community. In 1895, Newfield came to Emanu-El just out of rabbinic school. The young Hungarian had no idea that he would serve the city for the remainder of his career. Newfield worked to foster healthy relationships between the Jews and Christians of Birmingham; he taught Hebrew at Howard College, a Baptist school. In 1912, when 200 parishioners left First Presbyterian Church over doctrinal issues, Newfield invited their pastor Dr. Henry Edmonds to use Emanu-El’s sanctuary for their weekly prayer service. Though they expected to stay only for a short time, the eruption of World War I stalled the construction of the breakaway church’s new building, and the group ended up meeting at Emanu-El for over seven years. Edmonds and Newfield soon became close friends, and worked together in the future to promote further interfaith understanding. In 1928, the two ministers established a Birmingham chapter of the National Conference of Christians and Jews to promote the concept of universal brotherhood.

Newfield also worked as an active reformer to better the greater Birmingham community. In 1909, Newfield joined the board of Birmingham’s Associated Charities, which established milk stations and nurseries for the impoverished children of the city. Newfield adamantly lobbied the city to do more to help Birmingham’s underclass. He also fought against child labor, helped run the Birmingham chapter of the Red Cross, and helped to establish the Anti-Tuberculosis Society.

Building the Community

More and more, the German Jews of Emanu-El moved away from the Northside neighborhood and the Eastern European Jews of Knesseth Israel. They built large homes on fashionable streets like Highland Avenue. One of the most impressive belonged to Otto Marx, the son of early Birmingham settler Samuel Marx. The house was designed in the style of an Italian villa and was described by local papers as one of the “prettiest in the entire South.” In 1914, Emanu-El followed its members, building a new synagogue on Highland Avenue that could accommodate its growing membership. When their new building wasn’t ready by the time of the High Holidays, the congregation met at Southside Baptist Church. When it was finally completed, Emanu-El’s new synagogue served as a visible symbol of the prominence of Jews in Birmingham. With its massive columns and Italian Renaissance detailing, it is still considered to be one of Alabama’s most beautiful houses of worship.

As time went on, many members of Knesseth Israel increasingly found the Orthodoxy of the congregation too severe and anti-modern. Desiring a more liberal approach to their Orthodox traditions, a group of 44 Knesseth Israel members met at the home of Louis Pizitz to draft a constitution for a new congregation on April 25, 1908. Calling themselves Congregation Beth El, the group allowed for mixed seating of men and women, but at the same time, however, they also associated with the Union of Orthodox Hebrew Congregations. This seeming paradox perhaps represented the conflicting desires that existed within the new congregation. Though they wished to adopt progressive practices and rituals, Congregation Beth El also hoped to remain connected to the Orthodox tradition.The new congregation struggled initially. Realizing that the Northside was too small for two Orthodox congregations, Beth El built a new synagogue on Highland Avenue, only a block from Emanu-El’s building, in 1926.

Class and cultural divisions still separated the Eastern European Jews and the German Jews. While Knesseth Israel often had more members than Emanu-El, the Reform congregation was much wealthier. In the mid 1920s, when Knesseth Israel had over 300 member families, it had about $6,000 in annual income while Emanu-El, with 290 families, had $12,000 in income.

Another important reformer was Rabbi Morris Newfield of Temple Emanu-El, who was beloved both within and without his religious community. In 1895, Newfield came to Emanu-El just out of rabbinic school. The young Hungarian had no idea that he would serve the city for the remainder of his career. Newfield worked to foster healthy relationships between the Jews and Christians of Birmingham; he taught Hebrew at Howard College, a Baptist school. In 1912, when 200 parishioners left First Presbyterian Church over doctrinal issues, Newfield invited their pastor Dr. Henry Edmonds to use Emanu-El’s sanctuary for their weekly prayer service. Though they expected to stay only for a short time, the eruption of World War I stalled the construction of the breakaway church’s new building, and the group ended up meeting at Emanu-El for over seven years. Edmonds and Newfield soon became close friends, and worked together in the future to promote further interfaith understanding. In 1928, the two ministers established a Birmingham chapter of the National Conference of Christians and Jews to promote the concept of universal brotherhood.

Newfield also worked as an active reformer to better the greater Birmingham community. In 1909, Newfield joined the board of Birmingham’s Associated Charities, which established milk stations and nurseries for the impoverished children of the city. Newfield adamantly lobbied the city to do more to help Birmingham’s underclass. He also fought against child labor, helped run the Birmingham chapter of the Red Cross, and helped to establish the Anti-Tuberculosis Society.

Building the Community

More and more, the German Jews of Emanu-El moved away from the Northside neighborhood and the Eastern European Jews of Knesseth Israel. They built large homes on fashionable streets like Highland Avenue. One of the most impressive belonged to Otto Marx, the son of early Birmingham settler Samuel Marx. The house was designed in the style of an Italian villa and was described by local papers as one of the “prettiest in the entire South.” In 1914, Emanu-El followed its members, building a new synagogue on Highland Avenue that could accommodate its growing membership. When their new building wasn’t ready by the time of the High Holidays, the congregation met at Southside Baptist Church. When it was finally completed, Emanu-El’s new synagogue served as a visible symbol of the prominence of Jews in Birmingham. With its massive columns and Italian Renaissance detailing, it is still considered to be one of Alabama’s most beautiful houses of worship.

As time went on, many members of Knesseth Israel increasingly found the Orthodoxy of the congregation too severe and anti-modern. Desiring a more liberal approach to their Orthodox traditions, a group of 44 Knesseth Israel members met at the home of Louis Pizitz to draft a constitution for a new congregation on April 25, 1908. Calling themselves Congregation Beth El, the group allowed for mixed seating of men and women, but at the same time, however, they also associated with the Union of Orthodox Hebrew Congregations. This seeming paradox perhaps represented the conflicting desires that existed within the new congregation. Though they wished to adopt progressive practices and rituals, Congregation Beth El also hoped to remain connected to the Orthodox tradition.The new congregation struggled initially. Realizing that the Northside was too small for two Orthodox congregations, Beth El built a new synagogue on Highland Avenue, only a block from Emanu-El’s building, in 1926.

Class and cultural divisions still separated the Eastern European Jews and the German Jews. While Knesseth Israel often had more members than Emanu-El, the Reform congregation was much wealthier. In the mid 1920s, when Knesseth Israel had over 300 member families, it had about $6,000 in annual income while Emanu-El, with 290 families, had $12,000 in income.

Early-Twentieth Century Business

In the early-twentieth century, Jewish businessmen around the city engaged themselves in construction projects that permanently altered the Birmingham skyline. Rising high above First Avenue and 20th Street, the Brown Marx building was one of Birmingham’s first skyscrapers. First built in 1906 to house the offices of Otto Marx, a banker and department store executive, it sat in a cluster of four stone and steel towers. In fact, Birmingham residents called that block on First Avenue “the heaviest corner on earth,” because of the size of the buildings. In 1908, the Brown Marx building doubled in size to sixteen stories.

Dubbed “the Marshall Fields of Birmingham,” and supposedly the largest store south of the Ohio River, Loveman, Joseph, and Loeb loomed seven stories tall over its location on 3rd Avenue and covered over 40,000 square feet. One could get whatever they needed at the massive department store, everything from seersucker suits or toboggans. Its owners Moses Joseph, Emil Loeb, and Adolph Berman Loveman also became prominent members of Birmingham civic and charitable organizations. Loveman was a noted philanthropist. Joseph was president of the Birmingham Chamber of Commerce and helped expand the local steel industry.

The Klan & the Tribe

In 1918, the congregants of Emanu-El chose to dedicate their grand new temple with the phrase “My House shall be a house of prayer for all people.” Unfortunately, this message of interfaith harmony seemed out of step with the growing mood of nativism in Birmingham, best exemplified by the rise of the Ku Klux Klan. In the 1920s, the Klan presence in Birmingham had grown to well over 20,000 members. They dominated local politics for a number of years. Politicians and civic leaders who hoped to advance their careers often required Klan connections to win elections. The most notorious example of this was the young Birmingham lawyer Hugo Black, who joined the Klan before he was elected to the US Senate in 1926. After President Franklin Roosevelt appointed Black to the US Supreme Court in 1937, he ruled in favor of some of the most sweeping and important decisions to desegregate the South, including the 1954 case Brown v. Board of Education.

The resurgence of the Klan unsettled the Birmingham Jewish community. The Klan’s anti-immigrant and anti-Semitic rhetoric, as well as their violent tactics, caused alarm among members of all three Birmingham congregations. Due to intimidation and harassment on account of his Judaism, Chester Bandman resigned from his position as principal at Woodlawn High School. Despite such instances, most Jews simply adapted to life amidst the Klan; some even dealt with Klansmen in their daily businesses. At Cousin Joe’s Pawn Shop, owner Joe Denaburg saw Klansmen come in all the time to buy pistols from him. When the sale of white sheets increased rapidly, he knew it was not because of a sudden surge in bed buying.

Other Jews, however, refused to acquiesce to the unsettling political and social atmosphere. Irving Engel was an outspoken reformer and opponent of the convict lease system, in which convicted felons were sent to work in the coal mines rather than serve jail time. The system proved to be brutal for the convicts involved, almost 85% of them black. They endured beatings, unsanitary conditions, and terrifyingly high death rates. Engel, as Vice-Chairman of the statewide Campaign Committee for the Abolishment of the Convict Contract System, often spoke out publicly against this practice. The efforts of the Committee eventually led to the passage of reform legislation.

In the early-twentieth century, Jewish businessmen around the city engaged themselves in construction projects that permanently altered the Birmingham skyline. Rising high above First Avenue and 20th Street, the Brown Marx building was one of Birmingham’s first skyscrapers. First built in 1906 to house the offices of Otto Marx, a banker and department store executive, it sat in a cluster of four stone and steel towers. In fact, Birmingham residents called that block on First Avenue “the heaviest corner on earth,” because of the size of the buildings. In 1908, the Brown Marx building doubled in size to sixteen stories.

Dubbed “the Marshall Fields of Birmingham,” and supposedly the largest store south of the Ohio River, Loveman, Joseph, and Loeb loomed seven stories tall over its location on 3rd Avenue and covered over 40,000 square feet. One could get whatever they needed at the massive department store, everything from seersucker suits or toboggans. Its owners Moses Joseph, Emil Loeb, and Adolph Berman Loveman also became prominent members of Birmingham civic and charitable organizations. Loveman was a noted philanthropist. Joseph was president of the Birmingham Chamber of Commerce and helped expand the local steel industry.

The Klan & the Tribe

In 1918, the congregants of Emanu-El chose to dedicate their grand new temple with the phrase “My House shall be a house of prayer for all people.” Unfortunately, this message of interfaith harmony seemed out of step with the growing mood of nativism in Birmingham, best exemplified by the rise of the Ku Klux Klan. In the 1920s, the Klan presence in Birmingham had grown to well over 20,000 members. They dominated local politics for a number of years. Politicians and civic leaders who hoped to advance their careers often required Klan connections to win elections. The most notorious example of this was the young Birmingham lawyer Hugo Black, who joined the Klan before he was elected to the US Senate in 1926. After President Franklin Roosevelt appointed Black to the US Supreme Court in 1937, he ruled in favor of some of the most sweeping and important decisions to desegregate the South, including the 1954 case Brown v. Board of Education.

The resurgence of the Klan unsettled the Birmingham Jewish community. The Klan’s anti-immigrant and anti-Semitic rhetoric, as well as their violent tactics, caused alarm among members of all three Birmingham congregations. Due to intimidation and harassment on account of his Judaism, Chester Bandman resigned from his position as principal at Woodlawn High School. Despite such instances, most Jews simply adapted to life amidst the Klan; some even dealt with Klansmen in their daily businesses. At Cousin Joe’s Pawn Shop, owner Joe Denaburg saw Klansmen come in all the time to buy pistols from him. When the sale of white sheets increased rapidly, he knew it was not because of a sudden surge in bed buying.

Other Jews, however, refused to acquiesce to the unsettling political and social atmosphere. Irving Engel was an outspoken reformer and opponent of the convict lease system, in which convicted felons were sent to work in the coal mines rather than serve jail time. The system proved to be brutal for the convicts involved, almost 85% of them black. They endured beatings, unsanitary conditions, and terrifyingly high death rates. Engel, as Vice-Chairman of the statewide Campaign Committee for the Abolishment of the Convict Contract System, often spoke out publicly against this practice. The efforts of the Committee eventually led to the passage of reform legislation.

Hard Times Erase Old Boundaries

The Klan’s prominence in Birmingham faded by the end of the 1920s. However, with the sudden downward spiral of the world economy, Birmingham steel no longer produced the same magic it had before. The city’s poor neighborhoods bustled and heaved with the arrival of farmers from the surrounding barren countryside looking for jobs in the city. The competition for work was fierce and the city’s population suffered from high levels of unemployment.

All three Jewish congregations struggled financially in these years. Members of Temple Emanu-El had an increasingly hard time paying their temple dues while Knesseth Israel and Beth El faced similar financial challenges. Tough times meant that many Birmingham Jews had trouble continuing their religious practices. Kosher meat proved difficult to find. Many Jewish merchants decided that keeping Shabbat was too large a financial burden. Although the economy presented many problems, the 1930s was also a time in which Jewish cultural life flourished and many social barriers between Jews began to diminish.

Despite its financial hardships, Temple Beth El grew significantly in these years. By 1939, 370 families belonged to the congregation, making Beth El the largest synagogue in Alabama. In 1935, they hired Rabbi Abraham Mesch. Unlike Beth El’s previous rabbis who had only stayed a few years, Mesch became a fixture at Beth El, staying for over twenty-five years. Mesch’s commitment to Beth El likely helped consolidate and unify the congregation. Although it had started as a splinter group, Beth El remained on good terms with Knesseth Israel. The two shared a cemetery association and members of both congregations volunteered together in a joint Chevra Kadisha society for preparing the dead for burial. Many of Beth El’s publications included sections with updates from Knesseth Israel.

Relations between the Reform and Orthodox communities greatly improved as well. Rabbi Newfield of Temple Emanu-El frequently led services at Beth El before they hired a rabbi. In addition, the children of Jewish immigrants, having been born and raised in the United States, held less strictly to their parents’ religious practices and were more interested in mixing with the larger community. Many young men of the Northside, hoping to move up Birmingham’s social ladder, courted young women of German Jewish descent living on the upscale Southside. With this intermingling of communities, longstanding social divisions within the Jewish community of Birmingham slowly dissolved.

The Klan’s prominence in Birmingham faded by the end of the 1920s. However, with the sudden downward spiral of the world economy, Birmingham steel no longer produced the same magic it had before. The city’s poor neighborhoods bustled and heaved with the arrival of farmers from the surrounding barren countryside looking for jobs in the city. The competition for work was fierce and the city’s population suffered from high levels of unemployment.

All three Jewish congregations struggled financially in these years. Members of Temple Emanu-El had an increasingly hard time paying their temple dues while Knesseth Israel and Beth El faced similar financial challenges. Tough times meant that many Birmingham Jews had trouble continuing their religious practices. Kosher meat proved difficult to find. Many Jewish merchants decided that keeping Shabbat was too large a financial burden. Although the economy presented many problems, the 1930s was also a time in which Jewish cultural life flourished and many social barriers between Jews began to diminish.

Despite its financial hardships, Temple Beth El grew significantly in these years. By 1939, 370 families belonged to the congregation, making Beth El the largest synagogue in Alabama. In 1935, they hired Rabbi Abraham Mesch. Unlike Beth El’s previous rabbis who had only stayed a few years, Mesch became a fixture at Beth El, staying for over twenty-five years. Mesch’s commitment to Beth El likely helped consolidate and unify the congregation. Although it had started as a splinter group, Beth El remained on good terms with Knesseth Israel. The two shared a cemetery association and members of both congregations volunteered together in a joint Chevra Kadisha society for preparing the dead for burial. Many of Beth El’s publications included sections with updates from Knesseth Israel.

Relations between the Reform and Orthodox communities greatly improved as well. Rabbi Newfield of Temple Emanu-El frequently led services at Beth El before they hired a rabbi. In addition, the children of Jewish immigrants, having been born and raised in the United States, held less strictly to their parents’ religious practices and were more interested in mixing with the larger community. Many young men of the Northside, hoping to move up Birmingham’s social ladder, courted young women of German Jewish descent living on the upscale Southside. With this intermingling of communities, longstanding social divisions within the Jewish community of Birmingham slowly dissolved.

The Young Man’s Hebrew Association (YMHA) became the main locus of this intermingling. Founded in 1887, though not moving into a permanent building until 1920, the YMHA had originally been a center for the Eastern European Jews of the Northside. The German Jews mostly socialized at their more exclusive Phoenix Club, while a group of Orthodox Jews founded their own Progress Club in 1920. However, the YMHA proved to be more neutral ground. In its mission statement it hoped to “create a program to meet needs of Birmingham Jewry… to endeavor to bring the community into harmony.” Throughout the years, it served as a meeting spot for all sorts of Jewish organizations and the site of many social events. Eventually in the 1950s, it became the Levite Jewish Community Center, moving to a million dollar complex on Montclair road. There it had a pre-school, indoor pool, and track. A community theater group called the Center Players presented four shows annually for years. At a celebration for the YMHA’s 60th anniversary, Rabbi Milton Grafman commented that “I don’t think any Jewish community gets along as well as ours does.”

During the Depression years, the Jewish community also collaborated to focus its philanthropic efforts. In 1936, the Birmingham United Jewish Fund was founded with Dora Roth as its first leader. The Fund coordinated the efforts of numerous organizations to raise money for a variety of local and international Jewish causes. In its first year of existence, the Fund raised $24,000. Many years later, the Fund became the Birmingham Jewish Federation, which took on such projects as the founding of the N.E. Miles Jewish Day School and the resettlement of Jews fleeing oppressive regimes.

When World War II broke out in Europe, the urgent demand for steel and manufactured goods lifted Birmingham from its financial slump and provided jobs and relief to many of its needy citizens. Birmingham Jews took part in the war effort in a variety of ways, serving in the military, entertaining Jewish servicemen stationed nearby, and providing volunteer services at home.

WWII and Zionism in Birmingham

When World War II broke out in Europe, the urgent demand for steel and manufactured goods lifted Birmingham from its financial slump and provided jobs and relief to many of its needy citizens. Birmingham Jews took part in the war effort in a variety of ways, serving in the military, entertaining Jewish servicemen stationed nearby, and providing volunteer services at home.

The events of World War II and the Holocaust brought into stark relief the issue of a Jewish homeland. Prior to the war, a Zionist movement had existed in Birmingham for over forty years. After the publication of the book Der Judenstaat by Theodor Herzl in 1897, which outlined a plan to establish a Jewish state, a group of Birmingham Jews founded the Birmingham Zionists. Though initially small, the group met frequently at the YMHA for numerous years. Birmingham Jews also formed local chapters of Hadassah and Young Judea.

Positions on Zionism tended to run along ethnic and congregational lines. Eastern European and Orthodox Jews made up the vast majority of the Birmingham Zionists for most of its existence prior to World War II. Rabbi Mesch of Beth El was an ardent supporter and public advocate of Zionism. For the most part, the members of the Reform Emanu-El were against the establishment of a Jewish state. Rabbi Newfield argued that American Jews were citizens of the United States exclusively and that they could be loyal to their religion and people without supporting a Jewish state. Rabbi Newfield would change his opinion toward the end of his life, visiting with Alabama Senator John Bankhead in 1941 to urge his support for a Jewish state.

Largely due to the Nazi threat, membership in the Birmingham Zionists rose to 600 members by 1936; the city’s Zionist ranks continued to grow during and after the war. Abe Berkovitz led the group for a number of years, and actively lobbied the Alabama Legislature for a bill supporting the creation of a Jewish State. In 1943, he and other Zionists achieved success when both houses of the state government passed a resolution calling for the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine. When the United Nations declared their support of the formation of Israel in 1947, the overwhelming majority of Birmingham’s Jewish community celebrated. After Israel won its independence in 1948, the Birmingham Zionists worked to raise funds to help build the fledgling Jewish state. Together with the Birmingham Jewish Fund, the Zionists held annual Israel Bond Drives.

Among the members of Emanu-El, the issue of Zionism and Israel continued to be divisive. Rabbi Milton Grafman, who replaced the retired Rabbi Newfield in 1941, took a strong stance in favor of Israel. Several members of the congregation disagreed with Grafman’s views and in 1955, a small group broke away to form the Congregation of Reform Judaism. They were able to hire a rabbi, Harry Merfeld, who served the congregation for several years. When Merfeld resigned, the congregation went into decline, eventually disbanding in 1963.

During the Depression years, the Jewish community also collaborated to focus its philanthropic efforts. In 1936, the Birmingham United Jewish Fund was founded with Dora Roth as its first leader. The Fund coordinated the efforts of numerous organizations to raise money for a variety of local and international Jewish causes. In its first year of existence, the Fund raised $24,000. Many years later, the Fund became the Birmingham Jewish Federation, which took on such projects as the founding of the N.E. Miles Jewish Day School and the resettlement of Jews fleeing oppressive regimes.

When World War II broke out in Europe, the urgent demand for steel and manufactured goods lifted Birmingham from its financial slump and provided jobs and relief to many of its needy citizens. Birmingham Jews took part in the war effort in a variety of ways, serving in the military, entertaining Jewish servicemen stationed nearby, and providing volunteer services at home.

WWII and Zionism in Birmingham

When World War II broke out in Europe, the urgent demand for steel and manufactured goods lifted Birmingham from its financial slump and provided jobs and relief to many of its needy citizens. Birmingham Jews took part in the war effort in a variety of ways, serving in the military, entertaining Jewish servicemen stationed nearby, and providing volunteer services at home.

The events of World War II and the Holocaust brought into stark relief the issue of a Jewish homeland. Prior to the war, a Zionist movement had existed in Birmingham for over forty years. After the publication of the book Der Judenstaat by Theodor Herzl in 1897, which outlined a plan to establish a Jewish state, a group of Birmingham Jews founded the Birmingham Zionists. Though initially small, the group met frequently at the YMHA for numerous years. Birmingham Jews also formed local chapters of Hadassah and Young Judea.

Positions on Zionism tended to run along ethnic and congregational lines. Eastern European and Orthodox Jews made up the vast majority of the Birmingham Zionists for most of its existence prior to World War II. Rabbi Mesch of Beth El was an ardent supporter and public advocate of Zionism. For the most part, the members of the Reform Emanu-El were against the establishment of a Jewish state. Rabbi Newfield argued that American Jews were citizens of the United States exclusively and that they could be loyal to their religion and people without supporting a Jewish state. Rabbi Newfield would change his opinion toward the end of his life, visiting with Alabama Senator John Bankhead in 1941 to urge his support for a Jewish state.

Largely due to the Nazi threat, membership in the Birmingham Zionists rose to 600 members by 1936; the city’s Zionist ranks continued to grow during and after the war. Abe Berkovitz led the group for a number of years, and actively lobbied the Alabama Legislature for a bill supporting the creation of a Jewish State. In 1943, he and other Zionists achieved success when both houses of the state government passed a resolution calling for the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine. When the United Nations declared their support of the formation of Israel in 1947, the overwhelming majority of Birmingham’s Jewish community celebrated. After Israel won its independence in 1948, the Birmingham Zionists worked to raise funds to help build the fledgling Jewish state. Together with the Birmingham Jewish Fund, the Zionists held annual Israel Bond Drives.

Among the members of Emanu-El, the issue of Zionism and Israel continued to be divisive. Rabbi Milton Grafman, who replaced the retired Rabbi Newfield in 1941, took a strong stance in favor of Israel. Several members of the congregation disagreed with Grafman’s views and in 1955, a small group broke away to form the Congregation of Reform Judaism. They were able to hire a rabbi, Harry Merfeld, who served the congregation for several years. When Merfeld resigned, the congregation went into decline, eventually disbanding in 1963.

The Mid-Twentieth Century

In the 1950s, Knesseth Israel and Beth El enjoyed many productive years. In 1950, Beth El broke ground on a new educational building, naming it in honor of Rabbi Mesch. Knesseth Israel moved to a new building on Montevallo Road in 1955, becoming the last of the congregations to leave the Northside neighborhood for the Southside. However, that same year a lawsuit demonstrated that relations among the once close congregations had soured. On June 14, 1955, Knesseth Israel filed a bill of complaint asking that the joint cemetery association they shared with Beth El be dissolved. Besides several financial inequities, Knesseth Israel claimed that an “irreconcilable breach” had occurred between the two congregations on account of Beth El’s shifting ritual practices. Though Beth El claimed to retain ties with the Orthodox tradition, they had officially joined the Conservative Movement in 1944. Under Rabbi Mesch, the congregation had undergone many ritual changes, creating a choir and giving a greater role to women during services. Such changes had made Knesseth Israel uncomfortable sharing cemetery space and finances with the Conservative synagogue. After five years of litigation, Knesseth Israel dropped the suit in 1960, though the bitter feelings lingered.

In the 1950s, Knesseth Israel and Beth El enjoyed many productive years. In 1950, Beth El broke ground on a new educational building, naming it in honor of Rabbi Mesch. Knesseth Israel moved to a new building on Montevallo Road in 1955, becoming the last of the congregations to leave the Northside neighborhood for the Southside. However, that same year a lawsuit demonstrated that relations among the once close congregations had soured. On June 14, 1955, Knesseth Israel filed a bill of complaint asking that the joint cemetery association they shared with Beth El be dissolved. Besides several financial inequities, Knesseth Israel claimed that an “irreconcilable breach” had occurred between the two congregations on account of Beth El’s shifting ritual practices. Though Beth El claimed to retain ties with the Orthodox tradition, they had officially joined the Conservative Movement in 1944. Under Rabbi Mesch, the congregation had undergone many ritual changes, creating a choir and giving a greater role to women during services. Such changes had made Knesseth Israel uncomfortable sharing cemetery space and finances with the Conservative synagogue. After five years of litigation, Knesseth Israel dropped the suit in 1960, though the bitter feelings lingered.

The Crucible of Civil Rights

On April 16, 1963, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. wrote his famous “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.” Addressed to a group of local white clergy who had been critical of King’s tactics, the letter expressed King’s disappointment with their inaction. Among this group of local white clergy was Rabbi Milton Grafman of Temple Emanu-El. The situation surrounding the 1963 Birmingham protests and the exchanges between the city’s white clergy and King demonstrated the difficult position many faced who wanted both to pursue black civil rights and maintain the harmony of the city they cared for. For Rabbi Grafman and the Jewish community, who had long worked hard to improve Birmingham’s civic life, this dilemma made the year 1963 one of their most challenging.

Grafman was no stranger to controversial issues; he was infamous for starting sermons with the words “you’re not going to like what I have to say next.” In 1956, the University of Mississippi invited Rabbi Grafman, Reverend Alvin Kershaw, and other clergy to speak about their religions. However, when Reverend Kershaw publicly stated that he planned to donate money to the NAACP, university administrators responded by asking him not to attend. Angered by the University’s decision, Grafman and others refused the invitation to speak. For weeks following this incident, ardent segregationists bombarded Grafman’s home with threatening phone calls and mail. In 1963, Grafman signed a letter with other white clergy protesting Governor George Wallace’s impassioned defense of segregation during his inaugural address.

Other Birmingham Jews also worked for racial justice. In 1950, Mervyn Sterne of Temple Emanu-El helped establish Birmingham’s Interracial Committee, a group of twenty-five white members and twenty-five black members who met to discuss ways in which to peacefully lobby the city government to desegregate the city. In 1955, the Interracial Committee held a large conference on desegregating schools. The conference attracted a large, multiracial crowd of 800 people. After being persuaded by the Committee, city officials allowed the conference to have racially mixed seating, making it the largest integrated gathering of its time. The Interracial Committee’s efforts aroused strong opposition. After a barrage of White Citizen’s Council campaigning and Klan intimidation, the committee dissolved in 1956.

Fearing violence and marginalization, many in the Jewish community felt that desegregation was an issue better left untouched by Jews. The Klan still exerted a significant pull on local politics and loomed large in the minds of many Birmingham Jews. In 1958, these fears were almost realized when members of Congregation Beth El discovered 54 sticks of dynamite in one of their synagogue’s basement window wells. In a blue bag loaded with nitroglycerine, the dynamite had failed to detonate due to a faulty fuse. It would have easily destroyed the entire synagogue, coinciding with a similar bombing in Jacksonville, Florida. Though the synagogue received many messages of sympathy and support, the police never found those responsible. After the attempted bombing, two men in a passing car shouted to a custodian locking the doors of Temple Emanu-El, “you better get out of there, this one will be next.” The police were quick to arrest the men.

Civil rights activists usually did not receive the same police protection. The three-man City Commission, headed by Mayor Art Hanes and Public Safety Commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor, staunchly rejected any attempts to desegregate. In May of 1961, a group of young civil rights workers, known as “Freedom Riders” from the Congress of Racial Equality, received severe beatings from Klansmen at a Birmingham bus station, while Bull Connor’s police officers turned a blind eye. Later that same year, a federal ruling demanded that Birmingham desegregate its parks. Despite numerous protests from both civil rights workers and Birmingham business leaders, Mayor Hanes and the City Commission closed down the parks rather than desegregate them.

Many in the Jewish community saw the actions of the City Commission and Bull Connor as extremely detrimental to city and its public image. By way of the Chamber of Commerce and the Birmingham Downtown Improvement Association, Jews protested the segregationist positions of their city’s leaders. In an impassioned speech at a JCC event honoring him, William P. Engle asked: “Are we to follow our course already established as a progressive city, or are we going to become a city of infamy known for violence?” Rabbi Grafman also found these ruptures in the peace extremely unsettling.

In 1963, civil rights activists began a large-scale protest of segregation in Birmingham. Faced with an injunction to stop the protest, King announced he would march on City Hall. This caused an uproar in the city and many feared widespread violence. Rabbi Grafman and eight other members of the clergy met to share their concerns. The group was angered by King’s insistence on protesting before the recently elected mayor had a chance to pass desegregation legislation. As Rabbi Grafman sat at the typewriter, the group dictated a letter voicing their feelings. In their letter, published the next day in Birmingham’s newspapers, they essentially asked King to wait and give the moderate government a chance. Despite the letter, the protests continued.

On April 16, 1963, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. wrote his famous “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.” Addressed to a group of local white clergy who had been critical of King’s tactics, the letter expressed King’s disappointment with their inaction. Among this group of local white clergy was Rabbi Milton Grafman of Temple Emanu-El. The situation surrounding the 1963 Birmingham protests and the exchanges between the city’s white clergy and King demonstrated the difficult position many faced who wanted both to pursue black civil rights and maintain the harmony of the city they cared for. For Rabbi Grafman and the Jewish community, who had long worked hard to improve Birmingham’s civic life, this dilemma made the year 1963 one of their most challenging.

Grafman was no stranger to controversial issues; he was infamous for starting sermons with the words “you’re not going to like what I have to say next.” In 1956, the University of Mississippi invited Rabbi Grafman, Reverend Alvin Kershaw, and other clergy to speak about their religions. However, when Reverend Kershaw publicly stated that he planned to donate money to the NAACP, university administrators responded by asking him not to attend. Angered by the University’s decision, Grafman and others refused the invitation to speak. For weeks following this incident, ardent segregationists bombarded Grafman’s home with threatening phone calls and mail. In 1963, Grafman signed a letter with other white clergy protesting Governor George Wallace’s impassioned defense of segregation during his inaugural address.

Other Birmingham Jews also worked for racial justice. In 1950, Mervyn Sterne of Temple Emanu-El helped establish Birmingham’s Interracial Committee, a group of twenty-five white members and twenty-five black members who met to discuss ways in which to peacefully lobby the city government to desegregate the city. In 1955, the Interracial Committee held a large conference on desegregating schools. The conference attracted a large, multiracial crowd of 800 people. After being persuaded by the Committee, city officials allowed the conference to have racially mixed seating, making it the largest integrated gathering of its time. The Interracial Committee’s efforts aroused strong opposition. After a barrage of White Citizen’s Council campaigning and Klan intimidation, the committee dissolved in 1956.

Fearing violence and marginalization, many in the Jewish community felt that desegregation was an issue better left untouched by Jews. The Klan still exerted a significant pull on local politics and loomed large in the minds of many Birmingham Jews. In 1958, these fears were almost realized when members of Congregation Beth El discovered 54 sticks of dynamite in one of their synagogue’s basement window wells. In a blue bag loaded with nitroglycerine, the dynamite had failed to detonate due to a faulty fuse. It would have easily destroyed the entire synagogue, coinciding with a similar bombing in Jacksonville, Florida. Though the synagogue received many messages of sympathy and support, the police never found those responsible. After the attempted bombing, two men in a passing car shouted to a custodian locking the doors of Temple Emanu-El, “you better get out of there, this one will be next.” The police were quick to arrest the men.

Civil rights activists usually did not receive the same police protection. The three-man City Commission, headed by Mayor Art Hanes and Public Safety Commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor, staunchly rejected any attempts to desegregate. In May of 1961, a group of young civil rights workers, known as “Freedom Riders” from the Congress of Racial Equality, received severe beatings from Klansmen at a Birmingham bus station, while Bull Connor’s police officers turned a blind eye. Later that same year, a federal ruling demanded that Birmingham desegregate its parks. Despite numerous protests from both civil rights workers and Birmingham business leaders, Mayor Hanes and the City Commission closed down the parks rather than desegregate them.

Many in the Jewish community saw the actions of the City Commission and Bull Connor as extremely detrimental to city and its public image. By way of the Chamber of Commerce and the Birmingham Downtown Improvement Association, Jews protested the segregationist positions of their city’s leaders. In an impassioned speech at a JCC event honoring him, William P. Engle asked: “Are we to follow our course already established as a progressive city, or are we going to become a city of infamy known for violence?” Rabbi Grafman also found these ruptures in the peace extremely unsettling.

In 1963, civil rights activists began a large-scale protest of segregation in Birmingham. Faced with an injunction to stop the protest, King announced he would march on City Hall. This caused an uproar in the city and many feared widespread violence. Rabbi Grafman and eight other members of the clergy met to share their concerns. The group was angered by King’s insistence on protesting before the recently elected mayor had a chance to pass desegregation legislation. As Rabbi Grafman sat at the typewriter, the group dictated a letter voicing their feelings. In their letter, published the next day in Birmingham’s newspapers, they essentially asked King to wait and give the moderate government a chance. Despite the letter, the protests continued.

On April 12, 1963, Connor’s police force arrested King and 50 other protesters. Imprisoned, King made numerous notes to respond to the statement of the Birmingham clergy. The scathing words of “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” gained national attention. While Grafman felt that King had misjudged the group and their position, Jews from Northern cities were especially vitriolic in their criticism of Grafman. He found this hypocritical, and publicly pointed to covert racism in Northern cities.

A few weeks later, a group of 19 Conservative rabbis from the North flew into Birmingham to meet with protesters. The group of rabbis did not alert anyone in the Birmingham Jewish community before their arrival. Grafman was especially angered by their lack of outreach to Birmingham Jews because Rabbi Mesch of Beth El had died the year before and the Conservative synagogue still lacked a rabbi. Many Jews within the community saw the rabbis’ visit as further fodder to which the anti-Semitic Klan would respond.

After Bull Connor had unleashed dogs and firehoses on young protesters, providing the national media with disturbing images and further wounding the city’s reputation, representatives of Birmingham’s business community, city government, and civil rights groups met to establish a plan to lift most of the desegregation ordinances, including laws pertaining to stores, lunch counters, and the hiring of black employees. However, actual change came about slowly. Many Jewish store owners who complied with the plans endured harassment and vandalism. When Emil Hess reopened his department store Parisian’s without the sign prohibiting blacks from using the dressing rooms or sitting at the lunch counters, he received threatening phone calls and a brick thrown into his store’s window. Lovemen’s employees one day found a smoke bomb in their store.

The spring and summer of 1963 had drained Rabbi Grafman and tested the spiritual leader’s dedication to his community. During his Rosh Hashanah address to Emanu-El, only a few days after the bombing of the 16th Street Church which had killed four little girls, Grafman appeared before his congregation visibly exhausted and unprepared. He confessed to not having a sermon ready, and actually having forgotten it was the High Holidays. Having received so much criticism both from around the country and within his congregation, he defended his actions and explained he only did what he thought was best for the Jews of Birmingham and the city itself. He strongly urged his congregants to join with Christians and make meaningful changes in Birmingham.

By the end of the year, Birmingham’s new mayor, Albert Boutwell, had created the Committee on Group Relations, which addressed racial issues and further plans to desegregate. Grafman became an enthusiastic member. The struggle of that year had galvanized the rabbi, and he continued to advocate civil rights and interfaith understanding throughout his career. In 1964, he protested the presence of the Klan at the Alabama State Fair, earning him a million dollar defamation suit filed by Klan members. In 1970, a group broke away from the First Baptist Church because of the church’s refusal to accept black members. Grafman warmly invited the breakaway group to use Emanu-El’s sanctuary. In 1975, he became the first rabbi to lead the Minister’s Association of Greater Birmingham.

A few weeks later, a group of 19 Conservative rabbis from the North flew into Birmingham to meet with protesters. The group of rabbis did not alert anyone in the Birmingham Jewish community before their arrival. Grafman was especially angered by their lack of outreach to Birmingham Jews because Rabbi Mesch of Beth El had died the year before and the Conservative synagogue still lacked a rabbi. Many Jews within the community saw the rabbis’ visit as further fodder to which the anti-Semitic Klan would respond.

After Bull Connor had unleashed dogs and firehoses on young protesters, providing the national media with disturbing images and further wounding the city’s reputation, representatives of Birmingham’s business community, city government, and civil rights groups met to establish a plan to lift most of the desegregation ordinances, including laws pertaining to stores, lunch counters, and the hiring of black employees. However, actual change came about slowly. Many Jewish store owners who complied with the plans endured harassment and vandalism. When Emil Hess reopened his department store Parisian’s without the sign prohibiting blacks from using the dressing rooms or sitting at the lunch counters, he received threatening phone calls and a brick thrown into his store’s window. Lovemen’s employees one day found a smoke bomb in their store.

The spring and summer of 1963 had drained Rabbi Grafman and tested the spiritual leader’s dedication to his community. During his Rosh Hashanah address to Emanu-El, only a few days after the bombing of the 16th Street Church which had killed four little girls, Grafman appeared before his congregation visibly exhausted and unprepared. He confessed to not having a sermon ready, and actually having forgotten it was the High Holidays. Having received so much criticism both from around the country and within his congregation, he defended his actions and explained he only did what he thought was best for the Jews of Birmingham and the city itself. He strongly urged his congregants to join with Christians and make meaningful changes in Birmingham.

By the end of the year, Birmingham’s new mayor, Albert Boutwell, had created the Committee on Group Relations, which addressed racial issues and further plans to desegregate. Grafman became an enthusiastic member. The struggle of that year had galvanized the rabbi, and he continued to advocate civil rights and interfaith understanding throughout his career. In 1964, he protested the presence of the Klan at the Alabama State Fair, earning him a million dollar defamation suit filed by Klan members. In 1970, a group broke away from the First Baptist Church because of the church’s refusal to accept black members. Grafman warmly invited the breakaway group to use Emanu-El’s sanctuary. In 1975, he became the first rabbi to lead the Minister’s Association of Greater Birmingham.

The 1970s

After the tumult of the 1960s, Birmingham entered the 1970s eager to shed its old image and revive its slumping economy. Many Jewish business leaders took active roles in civic organizations like the Birmingham Downtown Improvement Association and the Chamber of Commerce that hoped to make over the run-down city. With new investments and the arrival of a handful of new financial institutions, the city’s skyline once again began to grow, something it had not done since before the Great Depression. In 1979, the city elected its first African American mayor, Richard Arrington, Jr.

For the Jewish community of Birmingham, the 1970s were also a time of growth and progress. The N.E. Miles Jewish Day School was founded in 1973. The JCC expanded and improved its facilities. In 1979, The Birmingham Jewish Foundation was created to serve as another avenue to finance Jewish organizations within the city. The three Jewish congregations continued to upkeep their traditions and homes. Around this time, Knesseth Israel dedicated a new mikvah. Temple Beth El conducted a major renovation of their building in 1972, adding a brand new chapel to their synagogue. Emanu-El continued its growth in membership.

After the tumult of the 1960s, Birmingham entered the 1970s eager to shed its old image and revive its slumping economy. Many Jewish business leaders took active roles in civic organizations like the Birmingham Downtown Improvement Association and the Chamber of Commerce that hoped to make over the run-down city. With new investments and the arrival of a handful of new financial institutions, the city’s skyline once again began to grow, something it had not done since before the Great Depression. In 1979, the city elected its first African American mayor, Richard Arrington, Jr.

For the Jewish community of Birmingham, the 1970s were also a time of growth and progress. The N.E. Miles Jewish Day School was founded in 1973. The JCC expanded and improved its facilities. In 1979, The Birmingham Jewish Foundation was created to serve as another avenue to finance Jewish organizations within the city. The three Jewish congregations continued to upkeep their traditions and homes. Around this time, Knesseth Israel dedicated a new mikvah. Temple Beth El conducted a major renovation of their building in 1972, adding a brand new chapel to their synagogue. Emanu-El continued its growth in membership.

The Strange Tale of a Youthful Spirit

In 1992, Kenji Awakura, a Japanese-American executive at the electronics company JVC, traveled to Birmingham to see the former home of one of his personal heroes, a poet. This American-born poet had achieved a devoted following in Japan. Awakura, like many men raised in Japan following World War II, carried a copy of the writer’s most famous poem “Youth” in his pocket as he walked down 15th Avenue to the poet’s home. This poet was none other than Samuel Ullman, the educational reformer and early Temple Emanu-El leader.

After retiring in his seventies, Ullman took up poetry in his spare time. Before his death in 1924, Ullman published one collection of his works called From the Summit of Years: Fourscore that sold relatively few copies. However, a copy of the book somehow fell into the hands of General Douglas MacArthur. The aging general became obsessed with one particular poem in the volume, “Youth.” In it, Ullman writes:

"Youth is not a time of life—it is a state of mind. It is not a matter of red cheeks, red lips and supple knees. It is a temper of the will; a quality of the imagination; a vigor of the emotions; it is a freshness of the deep springs of life. Youth means a temperamental predominance of courage over timidity, of the appetite for adventure over a life of ease. This often exists in a man of fifty, more than in a boy of twenty. Nobody grows old by merely living a number of years; people grow old by deserting their ideals."

The themes of the poem struck a personal chord with MacArthur and he kept a copy of it with him when he traveled. Following World War II, MacArthur posted a framed copy of the poem on his office wall in Tokyo. He would show it to guests stopping by for meetings. When MacArthur gave speeches to crowds of Japanese people, he quoted the poem at length.

For a people whose country had been ravaged by war, Ullman’s brief meditation on aging touched a nerve, and “Youth” slowly became an anthem of mass appeal to a Japan in the midst of reconstruction. Soon translations of the poem into Japanese began circulating around the country. Older business men carried the poem on note cards in their pockets. An organization formed called the Youth Foundation devoted to the ideals of the poem. From the Summit of Years: Fourscore became a national bestseller and remained popular in Japan long after its publication. Traces of Ullman are located throughout Japan, a country he never visited. In the lobby of the Daichi Insurance Company, the site of MacArthur’s old office, a sculpted bust of Ullman greets those who enter. The main library of the city Maebashi has an entire wing named after the Jewish American businessman and poet.

When Kenji Awakura made it to Ullman’s final home in Birmingham, where the poet had written his greatest work, he was disappointed to find that the building had fallen into disrepair. Partnering with the Japan American Society of Alabama and the University of Alabama Educational Foundation, Awakura led the fundraising effort to restore the house to its 1924 appearance. In 1993, the Ullman Museum was born and the youthful memory of one of Birmingham’s early Jewish founders persists.

In 1992, Kenji Awakura, a Japanese-American executive at the electronics company JVC, traveled to Birmingham to see the former home of one of his personal heroes, a poet. This American-born poet had achieved a devoted following in Japan. Awakura, like many men raised in Japan following World War II, carried a copy of the writer’s most famous poem “Youth” in his pocket as he walked down 15th Avenue to the poet’s home. This poet was none other than Samuel Ullman, the educational reformer and early Temple Emanu-El leader.