Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville: Historical Overview

|

Founded on the banks of the Ohio River in 1778 by Revolutionary War general George Rogers Clark, Louisville eventually emerged as a commercial trading center. Its economic potential was initially limited by its location at the falls of the Ohio, a long stretch of rapids that made river navigation treacherous. After the construction of a series of locks, which tamed this wild stretch of the river, Louisville developed into an important shipping port. With the addition of substantial railroad connections in the mid-19th century, linking the town to cities like Cincinnati, St. Louis, and Nashville, Louisville became the economic “gateway to the South” and one of the most important internal shipping points in the growing country. During the mid-19th century, as the nation moved westward, Louisville boomed. Between 1830 and 1852, the city’s population grew from 10,000 people to over 50,000. By 1900, more than 200,000 people lived in Kentucky’s largest city, which also developed into a manufacturing center for such products as distilled liquor, tobacco, and farm implements.

Jews were among those drawn to Louisville by its burgeoning economy. Eventually, a vibrant Jewish community would develop, lasting to this day. |

Stories of the Jewish Community in Louisville

B.H. Gotthelf, Adath Israel's first

spiritual leader

B.H. Gotthelf, Adath Israel's first

spiritual leader

Early Settlers

Perhaps the first Jew to settle in Louisville was Henry Hyman, who opened a tavern called the Western Coffeehouse in 1826. By 1829, Hyman was advertising “the most choice liquors” and such non-kosher foods as “pickled, stewed, or fried tripe, soused sturgeon, cold beef, cold ham, and oyster soup.” Hyman remained in Louisville until the 1850s. By the 1830s, a handful of other Jews moved to Louisville; most were born in the United States or England. According to historian Ira Rosenwaike, the majority owned clothing stores, while two were auctioneers. By 1832, at least ten Louisville Jews established the Israelite Benevolent Society, with Phineas Johnson (nee Israel) as its president. Johnson had moved to Louisville by 1831 and became an auctioneer. Most of the members had moved to Louisville just recently; only four of the ten listed members lived in the city in 1830. Most did not stay very long. By 1836, the society had dissolved as all but three of its members had moved away to cities like New Orleans and Charleston.

Congregations Form

It was not until German immigrants began to arrive in Louisville in the mid-1830s that a permanent Jewish community was established. Most, like Sigmund Griff, had initially lived in eastern cities like New York, and traveled west as peddlers. Griff, who had a hard time supporting his family in New York, did rather well as a peddler based out of Louisville in the 1840s, a decade which saw significant growth in the Jewish community. Most of these early Jewish residents concentrated in retail trade, primarily in dry goods but also in clothing and groceries. Only a small minority, less than 10%, were skilled artisans, whose numbers included a tailor, cigar maker, and cabinet makers.

By 1836, this small number of German Jews, perhaps six or seven families, had begun to worship together in the upstairs room of a local boarding house. A. Gerstle, a German-born dry goods merchant, led the Orthodox services as chazzan. In 1842, the group officially formed Adath Israel, the first Jewish congregation in Kentucky. Most of its 35 founders were German immigrants, while all of them were relatively recent arrivals to the city. None of the 35 founding men were listed in the city’s 1838 city directory. The congregation was initially Orthodox; its original charter decreed that any member who did not strictly observe the Sabbath or kosher laws could not lead prayers and those who married outside of the faith would be expelled from the congregation.

Perhaps the first Jew to settle in Louisville was Henry Hyman, who opened a tavern called the Western Coffeehouse in 1826. By 1829, Hyman was advertising “the most choice liquors” and such non-kosher foods as “pickled, stewed, or fried tripe, soused sturgeon, cold beef, cold ham, and oyster soup.” Hyman remained in Louisville until the 1850s. By the 1830s, a handful of other Jews moved to Louisville; most were born in the United States or England. According to historian Ira Rosenwaike, the majority owned clothing stores, while two were auctioneers. By 1832, at least ten Louisville Jews established the Israelite Benevolent Society, with Phineas Johnson (nee Israel) as its president. Johnson had moved to Louisville by 1831 and became an auctioneer. Most of the members had moved to Louisville just recently; only four of the ten listed members lived in the city in 1830. Most did not stay very long. By 1836, the society had dissolved as all but three of its members had moved away to cities like New Orleans and Charleston.

Congregations Form

It was not until German immigrants began to arrive in Louisville in the mid-1830s that a permanent Jewish community was established. Most, like Sigmund Griff, had initially lived in eastern cities like New York, and traveled west as peddlers. Griff, who had a hard time supporting his family in New York, did rather well as a peddler based out of Louisville in the 1840s, a decade which saw significant growth in the Jewish community. Most of these early Jewish residents concentrated in retail trade, primarily in dry goods but also in clothing and groceries. Only a small minority, less than 10%, were skilled artisans, whose numbers included a tailor, cigar maker, and cabinet makers.

By 1836, this small number of German Jews, perhaps six or seven families, had begun to worship together in the upstairs room of a local boarding house. A. Gerstle, a German-born dry goods merchant, led the Orthodox services as chazzan. In 1842, the group officially formed Adath Israel, the first Jewish congregation in Kentucky. Most of its 35 founders were German immigrants, while all of them were relatively recent arrivals to the city. None of the 35 founding men were listed in the city’s 1838 city directory. The congregation was initially Orthodox; its original charter decreed that any member who did not strictly observe the Sabbath or kosher laws could not lead prayers and those who married outside of the faith would be expelled from the congregation.

Adath Israel's 1868 synagogue

Adath Israel's 1868 synagogue

The young congregation grew quickly, reaching 76 members by 1847. The group soon bought land and began to plan the construction of a synagogue. There was internal dissension over the location, with some members complaining that the proposed site was too far from the downtown business district. As a result, they sold the land even though they had already laid the cornerstone, and bought a building which they converted into a house of worship. They dedicated the synagogue in 1849, and soon after hired B.H. Gotthelf to be their spiritual leader. Though not an ordained rabbi, Gotthelf served as chazzan and teacher and even gave sermons in German. The Occident newspaper described these early members of Adath Israel as men “of the humble class – men of worth, but not of wealth – who earn their bread by the sweat of their brow.”

Before too long, this characterization was no longer accurate as the members of Adath Israel became established and successful businessmen. According to an official history of the congregation written in 1906, Adath Israel soon made it harder to become a member in order to keep out “an undesirable element.” Perhaps not coincidentally, the city’s small population of Polish Jews founded their own congregation, Beth Israel, in 1851. Three years later, Beth Israel had 49 members. By 1857, the young congregation had its own building.

As Adath Israel became more exclusive, the congregation struggled over the issue of Reform. These debates could be heated, as when one traditional member threatened to burn down the synagogue if an organ were installed. Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, who lived only 130 miles away in Cincinnati, had a big influence on Adath Israel, visiting on several occasions. In 1857, the congregation became the first to adopt Wise’s Reform prayer book, Minhag America, even before his home congregation in Cincinnati did. In 1869, they formally adopted Reform Judaism, and were later a founding member of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, though the congregation rejected a resolution banning head coverings during worship services.

By 1859, Adath Israel had 117 members, and the group soon outgrew its building, voting to build a new one in 1864. In the midst of fundraising for the new synagogue, their old one burned to the ground in 1866. Two years later, Adath Israel dedicated a grand gothic synagogue on Broadway and Sixth Streets which cost the princely sum of $145,000. That same year, the congregation hired its first ordained rabbi, Leopold Kleeberg, while B.H. Gotthelf remained with the congregation as cantor. Ten years later, Kleeberg was replaced by Emil Hirsch, who, though he only stayed in Louisville for two years, had a significant impact on the 250-member congregation. Rabbi Adolph Moses was hired to fill Hirsch’s big shoes, and spent the next 21 years at Adath Israel. During Moses’ tenure, the congregation overwhelmingly adopted Sunday services instead of the traditional Saturday services, hoping that more members could attend on the Christian Sabbath since most worked on Saturday.

As the Jewish community of Louisville continued to grow, additional congregations were established. In 1880, a group of German immigrants split from Beth Israel due to their desire for religious reforms. Largely German-speaking, they chose not to join Adath Israel, which used English in their services by then. Instead, they formed a new congregation, B’rith Sholom. Although the group was made up of recent immigrants, they must have had significant financial means as they were able to construct their own synagogue by 1881. The congregation identified as Conservative initially, even as they instituted mixed gender seating and used an organ during services. Later, B’rith Sholom adopted the Reform Union Prayer Book, joining the UAHC in 1920. As late as 1901, most of its members were German, and services still included significant amounts of German in addition to Hebrew and English. Even the Orthodox Beth Israel showed signs of assimilation by the end of the 19th century. Changing its name to Adath Jeshurun, the congregation gradually adopted Conservative Judaism.

Adath Israel and B’rith Sholom represented two different generations of German Jewish immigrants in Louisville. Of the 13 B’rith Shalom trustees who could be found in the 1900 census (out of 16 total in 1901), all but two were born in Germany. Their average year of immigration was 1875, while only one came before the Civil War. Of the 23 men who served as an Adath Israel trustee between 1905 and 1907, only five were born in Germany; the rest were born in the United States, with most being native Kentuckians. Most of these native-born trustees were the children of German immigrants. Of the foreign born trustees, all but one came to the US before 1863. Both sets of trustees were roughly the same age, with an average age in the mid-forties. Less than a quarter of the Adath Israel trustees were merchants; 23% were professionals, including several lawyers, while another 23% were in the liquor distilling or wholesaling business, and 14% were in manufacturing. This occupational breakdown reflects the economically successful second generation immigrants who led the city’s oldest congregation. In contrast, over 60% of B’rith Sholom’s trustees were either merchants or retail store clerks, the common occupation of first generation immigrants. Adath Israel trustees were also wealthier; 83% of them had a live-in servant, and almost half had more than one. Only 31% of B’rith Sholom trustees had a servant, and none had more than one.

Before too long, this characterization was no longer accurate as the members of Adath Israel became established and successful businessmen. According to an official history of the congregation written in 1906, Adath Israel soon made it harder to become a member in order to keep out “an undesirable element.” Perhaps not coincidentally, the city’s small population of Polish Jews founded their own congregation, Beth Israel, in 1851. Three years later, Beth Israel had 49 members. By 1857, the young congregation had its own building.

As Adath Israel became more exclusive, the congregation struggled over the issue of Reform. These debates could be heated, as when one traditional member threatened to burn down the synagogue if an organ were installed. Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, who lived only 130 miles away in Cincinnati, had a big influence on Adath Israel, visiting on several occasions. In 1857, the congregation became the first to adopt Wise’s Reform prayer book, Minhag America, even before his home congregation in Cincinnati did. In 1869, they formally adopted Reform Judaism, and were later a founding member of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, though the congregation rejected a resolution banning head coverings during worship services.

By 1859, Adath Israel had 117 members, and the group soon outgrew its building, voting to build a new one in 1864. In the midst of fundraising for the new synagogue, their old one burned to the ground in 1866. Two years later, Adath Israel dedicated a grand gothic synagogue on Broadway and Sixth Streets which cost the princely sum of $145,000. That same year, the congregation hired its first ordained rabbi, Leopold Kleeberg, while B.H. Gotthelf remained with the congregation as cantor. Ten years later, Kleeberg was replaced by Emil Hirsch, who, though he only stayed in Louisville for two years, had a significant impact on the 250-member congregation. Rabbi Adolph Moses was hired to fill Hirsch’s big shoes, and spent the next 21 years at Adath Israel. During Moses’ tenure, the congregation overwhelmingly adopted Sunday services instead of the traditional Saturday services, hoping that more members could attend on the Christian Sabbath since most worked on Saturday.

As the Jewish community of Louisville continued to grow, additional congregations were established. In 1880, a group of German immigrants split from Beth Israel due to their desire for religious reforms. Largely German-speaking, they chose not to join Adath Israel, which used English in their services by then. Instead, they formed a new congregation, B’rith Sholom. Although the group was made up of recent immigrants, they must have had significant financial means as they were able to construct their own synagogue by 1881. The congregation identified as Conservative initially, even as they instituted mixed gender seating and used an organ during services. Later, B’rith Sholom adopted the Reform Union Prayer Book, joining the UAHC in 1920. As late as 1901, most of its members were German, and services still included significant amounts of German in addition to Hebrew and English. Even the Orthodox Beth Israel showed signs of assimilation by the end of the 19th century. Changing its name to Adath Jeshurun, the congregation gradually adopted Conservative Judaism.

Adath Israel and B’rith Sholom represented two different generations of German Jewish immigrants in Louisville. Of the 13 B’rith Shalom trustees who could be found in the 1900 census (out of 16 total in 1901), all but two were born in Germany. Their average year of immigration was 1875, while only one came before the Civil War. Of the 23 men who served as an Adath Israel trustee between 1905 and 1907, only five were born in Germany; the rest were born in the United States, with most being native Kentuckians. Most of these native-born trustees were the children of German immigrants. Of the foreign born trustees, all but one came to the US before 1863. Both sets of trustees were roughly the same age, with an average age in the mid-forties. Less than a quarter of the Adath Israel trustees were merchants; 23% were professionals, including several lawyers, while another 23% were in the liquor distilling or wholesaling business, and 14% were in manufacturing. This occupational breakdown reflects the economically successful second generation immigrants who led the city’s oldest congregation. In contrast, over 60% of B’rith Sholom’s trustees were either merchants or retail store clerks, the common occupation of first generation immigrants. Adath Israel trustees were also wealthier; 83% of them had a live-in servant, and almost half had more than one. Only 31% of B’rith Sholom trustees had a servant, and none had more than one.

Adath Israel's grand new synagogue, dedicated in 1906.

Adath Israel's grand new synagogue, dedicated in 1906.

The members of Adath Israel, B’rith Sholom, and Adath Jeshurun were soon joined by growing numbers of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe and the Russian Empire. Rather than join the city’s existing synagogues, these newly arrived immigrants established congregations of their own. In 1877, a group founded B’nai Jacob, while ten years later another group of immigrants founded Beth Hamedrash Hagodol. In 1893, recent immigrants who preferred the Sephardic-style Hasidic ritual founded Anshei Sfard, which purchased B’rith Sholom’s old building in 1903. In 1922, yet another Orthodox congregation, Agudath Achim, was established.

According to the American Jewish Year Book, an estimated 8,000 Jews lived in Louisville by 1907. There were six different congregations: two Reform; one conservative; and three Orthodox. The two largest congregations were Reform: Adath Israel, with 400 members; and B’rith Sholom, with 160 members. The Orthodox congregations had 320 members combined, while the smallest congregation was the Conservative Adath Jeshurun, with 75 members. Adath Israel was by far the wealthiest congregation, with more annual income than the other five congregations combined.

According to the American Jewish Year Book, an estimated 8,000 Jews lived in Louisville by 1907. There were six different congregations: two Reform; one conservative; and three Orthodox. The two largest congregations were Reform: Adath Israel, with 400 members; and B’rith Sholom, with 160 members. The Orthodox congregations had 320 members combined, while the smallest congregation was the Conservative Adath Jeshurun, with 75 members. Adath Israel was by far the wealthiest congregation, with more annual income than the other five congregations combined.

Keneseth Israel's 1929 synagogue. Photo courtesy of

Julian Preisler

Keneseth Israel's 1929 synagogue. Photo courtesy of

Julian Preisler

The Development of the Orthodox Community

Much of the growth in the city’s Jewish population around the turn of the century was due to the influx of new arrivals from Eastern Europe. These Yiddish-speaking immigrants clustered around the Preston Street area in downtown Louisville. Most were petty merchants, with small shops on Market Street, although several were tailors or cigar makers. The neighborhood became Louisville’s version of New York’s Lowest East Side, with Orthodox shuls, kosher markets, and a rich Yiddish culture. In the 1890s, a group founded a Yiddish Dramatic Society, which put on original plays in addition to the classics, such as “Der Yidisher Hamlet.” These immigrants could also buy the Yiddish newspapers that were published in larger cities in the North.

Perhaps the most interesting organization founded by these immigrants was the Vaad Haer (community council), modeled after the kehillah, which exercised authority in European Jewish communities. In Louisville, the Vaad Haer supervised and certified the production of kosher meat, ran the mikvah (ritual bath), and established the Louisville Hebrew School to teach Hebrew and Jewish texts to their children. The Vaad Haer also hired a chief Orthodox rabbi for the city, A.L. Zarchy, in 1903. Rabbi Zarchy became the spiritual leader of all the city’s Orthodox congregations, receiving his salary from the Vaad.

Over time, the individual congregations began to chafe under the Vaad and Rabbi Zarchy’s authority. In the 1910s, Anshei Sfard hired its own rabbi, which angered Rabbi Zarchy, who often snubbed his Orthodox colleague. The city’s other Orthodox congregations isolated Anshei Sfard for this attempted independence. In 1926, B’nai Jacob and Beth Hamedrash Hagodol, both facing financial troubles, merged to form Keneseth Israel. The new combined congregation hired its own Orthodox rabbi, Albert Mandelbaum, in 1927. Soon there was friction between the two Orthodox rabbis and questions over their respective authority. These issues came to a head after Rabbi Zarchy died in 1932, after serving as Louisville’s head Orthodox rabbi for almost 30 years. His replacement, Lithuanian-born Ben Zion Notelevitz, also became the acting rabbi of Keneseth Israel. This dual role created tension as Keneseth Israel wanted a rabbi who could give sermons in English, instead of the Yiddish used by Rabbi Notelevitz.

When Keneseth Israel decided to hire its own rabbi, Benjamin Brilliant, conflicts between the two rabbis became bitter. After Rabbi Notelevitz made negative comments about the congregation, Keneseth Israel barred him from their pulpit. Notelevitz appealed to the Orthodox leaders of Yeshiva University, who ruled that he should still be considered the senior rabbi of Keneseth Israel and must be allowed onto its bimah. Notelevitz then tried to get Rabbi Brilliant’s rabbinic ordination rescinded, though this effort failed. Finally, in 1937, the members of Keneseth Israel voted to pull out of the Vaad Haer and declared themselves an autonomous congregation. Rabbi Notelevitz left town soon after, and Louisville never again had a chief rabbi. The Vaad declined in importance, only retaining its authority over the certification of kosher meat. The demise of the Vaad Haer represented the triumph of the American style of congregational authority and the end of the European model of centralized Jewish community control.

Gaining its independence only led to additional conflict and controversy at Keneseth Israel as the congregation struggled over how to maintain traditional Judaism while the native-born second generation came of age. The congregation grew significantly, numbering 500 families when they dedicated their new synagogue in 1929. After World War II, the younger members of the congregation began to push for mixed-gender seating. In 1950, a group of female members held “sit-down strikes” in the downstairs men’s section during services. During one of these demonstrations, the police were called to restore order, and some members threatened a court injunction to stop the protests. Rabbi Brilliant supported the traditionalists and would refuse to continue services while women were sitting in the men's section. Finally, the board sought to strike a compromise by allowing women to sit on the main floor of the sanctuary separated from the men by a mechitza, though this solution did not satisfy the protesters. Finally, after Rabbi Brilliant left Keneseth Israel in 1952, the congregation voted to institute mixed seating in the middle section of the sanctuary, with separate sections for men and women at the sides.

Much of the growth in the city’s Jewish population around the turn of the century was due to the influx of new arrivals from Eastern Europe. These Yiddish-speaking immigrants clustered around the Preston Street area in downtown Louisville. Most were petty merchants, with small shops on Market Street, although several were tailors or cigar makers. The neighborhood became Louisville’s version of New York’s Lowest East Side, with Orthodox shuls, kosher markets, and a rich Yiddish culture. In the 1890s, a group founded a Yiddish Dramatic Society, which put on original plays in addition to the classics, such as “Der Yidisher Hamlet.” These immigrants could also buy the Yiddish newspapers that were published in larger cities in the North.

Perhaps the most interesting organization founded by these immigrants was the Vaad Haer (community council), modeled after the kehillah, which exercised authority in European Jewish communities. In Louisville, the Vaad Haer supervised and certified the production of kosher meat, ran the mikvah (ritual bath), and established the Louisville Hebrew School to teach Hebrew and Jewish texts to their children. The Vaad Haer also hired a chief Orthodox rabbi for the city, A.L. Zarchy, in 1903. Rabbi Zarchy became the spiritual leader of all the city’s Orthodox congregations, receiving his salary from the Vaad.

Over time, the individual congregations began to chafe under the Vaad and Rabbi Zarchy’s authority. In the 1910s, Anshei Sfard hired its own rabbi, which angered Rabbi Zarchy, who often snubbed his Orthodox colleague. The city’s other Orthodox congregations isolated Anshei Sfard for this attempted independence. In 1926, B’nai Jacob and Beth Hamedrash Hagodol, both facing financial troubles, merged to form Keneseth Israel. The new combined congregation hired its own Orthodox rabbi, Albert Mandelbaum, in 1927. Soon there was friction between the two Orthodox rabbis and questions over their respective authority. These issues came to a head after Rabbi Zarchy died in 1932, after serving as Louisville’s head Orthodox rabbi for almost 30 years. His replacement, Lithuanian-born Ben Zion Notelevitz, also became the acting rabbi of Keneseth Israel. This dual role created tension as Keneseth Israel wanted a rabbi who could give sermons in English, instead of the Yiddish used by Rabbi Notelevitz.

When Keneseth Israel decided to hire its own rabbi, Benjamin Brilliant, conflicts between the two rabbis became bitter. After Rabbi Notelevitz made negative comments about the congregation, Keneseth Israel barred him from their pulpit. Notelevitz appealed to the Orthodox leaders of Yeshiva University, who ruled that he should still be considered the senior rabbi of Keneseth Israel and must be allowed onto its bimah. Notelevitz then tried to get Rabbi Brilliant’s rabbinic ordination rescinded, though this effort failed. Finally, in 1937, the members of Keneseth Israel voted to pull out of the Vaad Haer and declared themselves an autonomous congregation. Rabbi Notelevitz left town soon after, and Louisville never again had a chief rabbi. The Vaad declined in importance, only retaining its authority over the certification of kosher meat. The demise of the Vaad Haer represented the triumph of the American style of congregational authority and the end of the European model of centralized Jewish community control.

Gaining its independence only led to additional conflict and controversy at Keneseth Israel as the congregation struggled over how to maintain traditional Judaism while the native-born second generation came of age. The congregation grew significantly, numbering 500 families when they dedicated their new synagogue in 1929. After World War II, the younger members of the congregation began to push for mixed-gender seating. In 1950, a group of female members held “sit-down strikes” in the downstairs men’s section during services. During one of these demonstrations, the police were called to restore order, and some members threatened a court injunction to stop the protests. Rabbi Brilliant supported the traditionalists and would refuse to continue services while women were sitting in the men's section. Finally, the board sought to strike a compromise by allowing women to sit on the main floor of the sanctuary separated from the men by a mechitza, though this solution did not satisfy the protesters. Finally, after Rabbi Brilliant left Keneseth Israel in 1952, the congregation voted to institute mixed seating in the middle section of the sanctuary, with separate sections for men and women at the sides.

Adath Yeshurun's 1919 synagogue. Photo courtesy of

Julian Preisler

Adath Yeshurun's 1919 synagogue. Photo courtesy of

Julian Preisler

The Growth of the Reform and Conservative Communities

The city’s non-Orthodox congregations continued to flourish during the first half of the 20th century. Adath Jeshurun hired Rabbi J.J. Gittleman, a graduate of the Jewish Theological Seminary, in 1917. Gittleman led Adath Jeshurun for the next 48 years, during which the Conservative congregation grew from 50 families to 600. The congregation built a new synagogue in 1919, but soon outgrew it, and had to hold High Holiday services in the city’s Memorial Auditorium after World War II.

Adath Israel had outgrown its 1868 synagogue by the turn of the century. The newly formed Sisterhood pushed hard for a new building, a process that was helped along by a roof leak, which caused part of the ceiling to collapse in 1904. The congregation voted to build a new temple on 3rd Street, which was completed in 1906. During the dedication weekend, ten different rabbis from such cities as Mobile, Cincinnati, Lexington and Paducah, Kentucky, Philadelphia, New Orleans, Chicago, St. Louis, and Cleveland took part in the grandiose ceremonies. Rabbi H.G. Enelow led the flourishing congregation, taking over from Rabbi Moses when he died in 1902. When Enelow left in 1912 to take over the pulpit at Temple Emanu El in New York, he was replaced by Joseph Rauch, who would lead Adath Israel for the next 45 years. In 1932, the congregation discontinued its Sunday services, which it had been holding since 1891, and replaced it with a Friday night service. Some members complained about the change; when one was asked why he cared since he rarely attended services anyway, he answered, “I would much rather not attend services on Sunday morning than not attend them on Friday evening.”

Rabbi Rauch emerged as the recognized spokesman for the Louisville Jewish community, serving as a bridge to the Gentile population. Rauch was very involved in interfaith efforts, often preaching from church pulpits. The rabbi was extremely active in civic affairs, spending 17 years as president of the board of the Louisville Public Library; it was during his tenure that the library racially integrated its facilities. Rabbi Rauch also served long terms on the board of the local Red Cross and the University of Louisville. When he died, the flags at city hall flew at half mast. The local planetarium and a nearby school for children with developmental disabilities were named for the rabbi.

The city’s non-Orthodox congregations continued to flourish during the first half of the 20th century. Adath Jeshurun hired Rabbi J.J. Gittleman, a graduate of the Jewish Theological Seminary, in 1917. Gittleman led Adath Jeshurun for the next 48 years, during which the Conservative congregation grew from 50 families to 600. The congregation built a new synagogue in 1919, but soon outgrew it, and had to hold High Holiday services in the city’s Memorial Auditorium after World War II.

Adath Israel had outgrown its 1868 synagogue by the turn of the century. The newly formed Sisterhood pushed hard for a new building, a process that was helped along by a roof leak, which caused part of the ceiling to collapse in 1904. The congregation voted to build a new temple on 3rd Street, which was completed in 1906. During the dedication weekend, ten different rabbis from such cities as Mobile, Cincinnati, Lexington and Paducah, Kentucky, Philadelphia, New Orleans, Chicago, St. Louis, and Cleveland took part in the grandiose ceremonies. Rabbi H.G. Enelow led the flourishing congregation, taking over from Rabbi Moses when he died in 1902. When Enelow left in 1912 to take over the pulpit at Temple Emanu El in New York, he was replaced by Joseph Rauch, who would lead Adath Israel for the next 45 years. In 1932, the congregation discontinued its Sunday services, which it had been holding since 1891, and replaced it with a Friday night service. Some members complained about the change; when one was asked why he cared since he rarely attended services anyway, he answered, “I would much rather not attend services on Sunday morning than not attend them on Friday evening.”

Rabbi Rauch emerged as the recognized spokesman for the Louisville Jewish community, serving as a bridge to the Gentile population. Rauch was very involved in interfaith efforts, often preaching from church pulpits. The rabbi was extremely active in civic affairs, spending 17 years as president of the board of the Louisville Public Library; it was during his tenure that the library racially integrated its facilities. Rabbi Rauch also served long terms on the board of the local Red Cross and the University of Louisville. When he died, the flags at city hall flew at half mast. The local planetarium and a nearby school for children with developmental disabilities were named for the rabbi.

Isaac Bernheim

Isaac Bernheim

Geographic Changes in the Post-War Era

After World War II, many Louisville Jews moved to the more suburban eastern part of the city. In response, their synagogues soon followed. B’rith Shalom sold its downtown building in 1950, and built a new temple in the Highlands neighborhood in 1951. Adath Jeshurun faced this same dilemma when they a built a new education building in the Highlands neighborhood in 1951. Six years later, the congregation built a new synagogue in the Highlands. Anshei Sfard was forced to move when a new expressway was planned to go through their building. They moved to the eastern part of the city, adjacent to the new Jewish Community Center, in 1957. Keneseth Israel dedicated its east end synagogue in 1964. Adath Israel was the last congregation to move out of downtown, dedicating its new suburban temple in 1980.

Business and Civic Life

Jews have been an important part of Louisville’s economic and civic life since the mid-19th century. They were heavily involved in one of Louisville’s signature industries: the manufacture and sale of Kentucky bourbon. German-born Isaac Bernheim came to the United States after the Civil War and started out as a peddler. He later settled in Paducah, Kentucky, working as a bookkeeper for a large firm. He brought his brother Bernard over from Germany in 1869. The Bernheim brothers impressed the president of the City National Bank in Louisville, who helped to finance the wholesale liquor business they started in 1872. In 1888, the company moved to Louisville and the brothers purchased a local distillery. Bernheim created the I.W. Harper brand of whiskey, as his distillery business became extremely successful. Bernheim became an important civic leader and major philanthropist. Bernheim donated statues of Abraham Lincoln and Thomas Jefferson to the city, which are now displayed in front of the public library and courthouse. In 1929, he established the 14,000-acre Bernheim Arboretum and Research Forest. Bernheim was also very active in the local Jewish community. He was a major funder of the Young Men’s Hebrew Association, and served as its president. After Hitler came to power in his home country of Germany, Bernheim sponsored over 300 Jewish refugees before his death in 1945 at age 96.

After World War II, many Louisville Jews moved to the more suburban eastern part of the city. In response, their synagogues soon followed. B’rith Shalom sold its downtown building in 1950, and built a new temple in the Highlands neighborhood in 1951. Adath Jeshurun faced this same dilemma when they a built a new education building in the Highlands neighborhood in 1951. Six years later, the congregation built a new synagogue in the Highlands. Anshei Sfard was forced to move when a new expressway was planned to go through their building. They moved to the eastern part of the city, adjacent to the new Jewish Community Center, in 1957. Keneseth Israel dedicated its east end synagogue in 1964. Adath Israel was the last congregation to move out of downtown, dedicating its new suburban temple in 1980.

Business and Civic Life

Jews have been an important part of Louisville’s economic and civic life since the mid-19th century. They were heavily involved in one of Louisville’s signature industries: the manufacture and sale of Kentucky bourbon. German-born Isaac Bernheim came to the United States after the Civil War and started out as a peddler. He later settled in Paducah, Kentucky, working as a bookkeeper for a large firm. He brought his brother Bernard over from Germany in 1869. The Bernheim brothers impressed the president of the City National Bank in Louisville, who helped to finance the wholesale liquor business they started in 1872. In 1888, the company moved to Louisville and the brothers purchased a local distillery. Bernheim created the I.W. Harper brand of whiskey, as his distillery business became extremely successful. Bernheim became an important civic leader and major philanthropist. Bernheim donated statues of Abraham Lincoln and Thomas Jefferson to the city, which are now displayed in front of the public library and courthouse. In 1929, he established the 14,000-acre Bernheim Arboretum and Research Forest. Bernheim was also very active in the local Jewish community. He was a major funder of the Young Men’s Hebrew Association, and served as its president. After Hitler came to power in his home country of Germany, Bernheim sponsored over 300 Jewish refugees before his death in 1945 at age 96.

Samuel Grabfelder worked as a traveling salesman for a large wholesale liquor company after the Civil War. Grabfelder opened his own liquor business in 1879, becoming a prominent merchant in the field. Grabfelder was very active in Jewish affairs, serving as president of Adath Israel as well as the Jewish Elderly Home in Cleveland. He was also a major financial contributor to the National Jewish Hospital for Consumptives in Denver, serving as president of its board. Louis Barkhouse started in the whiskey brokerage business in the late 19th century, but soon moved into distilling. By 1901, his company was one of the largest distillers in the state. Several other Louisville Jews were involved in the liquor trade, especially after prohibition was repealed. Once whiskey was made legal again in 1933, five Shapira brothers, who already owned a department store, invested in a new distillery business. Their Heaven Hill brand is currently the largest family owned distillery business in the country.

At the turn of the 20th century, Louisville Jews owned a wide array of retail stores, including hat, shoe, furniture, drugs, jewelry, and cigar stores. Isaac Rosenbaum came to Louisville in the 1870s as a peddler who bought hides and furs on his travels. He established Isaac Rosenbaum & Sons, which eventually became the largest wool dealer in the South, handling 6 million pounds of it each year. Dann Byck opened a shoe store in downtown Louisville in 1902, which later grew into a successful women’s clothing store. In the 1970s and 80s, the store expanded into suburban malls in the area, although all of the locations were closed by 1991.

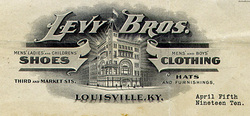

Louisville Jews were also involved in the more traditional retail dry goods trade. Brothers Henry and Moses Levy, who emigrated to the U.S. from Prussia, opened a clothing and tailoring business in the 1860s. From this small beginning grew the Levy Brothers store, which specialized in men’s clothing, and served Louisville residents for over a century. In 1893, the Levy brothers built a new 5-story Romanesque building to house their growing business. By 1901, the store employed 125 people. Levy Brothers continued to flourish in the 20th century as the next two generations of family members ran the business. Finally, in 1980, the family closed the historic downtown location, and seven years later, closed the last Levy Brothers location in Louisville. Henry Kaufman first settled in Louisville in 1873; seven years later he opened the Kaufman-Straus store with partner Benjamin Straus. By 1901, the firm was described in a local history as “one of the finest business houses in Louisville” and eventually became the city’s second largest department store. The store remained in business until 1971. Russian-born Ben Snyder opened a small store in 1910 that eventually grew into one of the city’s largest department stores. When Ben died in 1946, his wife Jessie took over the business. Eventually the Ben Snyder Store became a chain with eight locations, including six in Louisville. In 1987, the family sold the business to a Pennsylvania-based company, making it the last major locally owned department store in the city.

In the late 19th century, Louisville Jews became active in the city’s manufacturing industry. Solomon Hilpp started out as a tailor, but eventually built a successful clothing business which employed 250 people in 1901. That same year, Samuel LeJeune was one of the city’s largest cigar makers. In 1881, David Hirsch founded Hirsch’s Cider and Vinegar Works, which later grew into the Paramount Pickle Company. This involvement in manufacturing continued into the 20th century. In 1919, brothers Herman, Bernard, and Sidney Rosenblum started the Enro Shirt Company, which remained in business for the next 50 years.

Louisville Jews also distinguished themselves in the professions. Several Louisville Jews practiced law and medicine in the 19th century, long before such occupations became common for American Jews. Both Aaron Kohn and Lafayette Joseph were prominent local attorneys, and served a period as local prosecutors. They also were both elected to the city council in the 1880s. Isador Bloom, a Louisville native, started practicing medicine in 1883 after finishing Harvard Medical School, becoming one of the foremost dermatologists in the country. Dr. Bloom also taught at the University of Louisville and spent many years on the staff of city hospital.

At the turn of the 20th century, Louisville Jews owned a wide array of retail stores, including hat, shoe, furniture, drugs, jewelry, and cigar stores. Isaac Rosenbaum came to Louisville in the 1870s as a peddler who bought hides and furs on his travels. He established Isaac Rosenbaum & Sons, which eventually became the largest wool dealer in the South, handling 6 million pounds of it each year. Dann Byck opened a shoe store in downtown Louisville in 1902, which later grew into a successful women’s clothing store. In the 1970s and 80s, the store expanded into suburban malls in the area, although all of the locations were closed by 1991.

Louisville Jews were also involved in the more traditional retail dry goods trade. Brothers Henry and Moses Levy, who emigrated to the U.S. from Prussia, opened a clothing and tailoring business in the 1860s. From this small beginning grew the Levy Brothers store, which specialized in men’s clothing, and served Louisville residents for over a century. In 1893, the Levy brothers built a new 5-story Romanesque building to house their growing business. By 1901, the store employed 125 people. Levy Brothers continued to flourish in the 20th century as the next two generations of family members ran the business. Finally, in 1980, the family closed the historic downtown location, and seven years later, closed the last Levy Brothers location in Louisville. Henry Kaufman first settled in Louisville in 1873; seven years later he opened the Kaufman-Straus store with partner Benjamin Straus. By 1901, the firm was described in a local history as “one of the finest business houses in Louisville” and eventually became the city’s second largest department store. The store remained in business until 1971. Russian-born Ben Snyder opened a small store in 1910 that eventually grew into one of the city’s largest department stores. When Ben died in 1946, his wife Jessie took over the business. Eventually the Ben Snyder Store became a chain with eight locations, including six in Louisville. In 1987, the family sold the business to a Pennsylvania-based company, making it the last major locally owned department store in the city.

In the late 19th century, Louisville Jews became active in the city’s manufacturing industry. Solomon Hilpp started out as a tailor, but eventually built a successful clothing business which employed 250 people in 1901. That same year, Samuel LeJeune was one of the city’s largest cigar makers. In 1881, David Hirsch founded Hirsch’s Cider and Vinegar Works, which later grew into the Paramount Pickle Company. This involvement in manufacturing continued into the 20th century. In 1919, brothers Herman, Bernard, and Sidney Rosenblum started the Enro Shirt Company, which remained in business for the next 50 years.

Louisville Jews also distinguished themselves in the professions. Several Louisville Jews practiced law and medicine in the 19th century, long before such occupations became common for American Jews. Both Aaron Kohn and Lafayette Joseph were prominent local attorneys, and served a period as local prosecutors. They also were both elected to the city council in the 1880s. Isador Bloom, a Louisville native, started practicing medicine in 1883 after finishing Harvard Medical School, becoming one of the foremost dermatologists in the country. Dr. Bloom also taught at the University of Louisville and spent many years on the staff of city hospital.

Louis Dembitz

Louis Dembitz

Prominent Jewish Families of Louisville

Perhaps the most notable Jewish lawyer in Louisville was Louis Dembitz. Born in Posen, Dembitz came to the United States in 1849. After training in the law in Cincinnati, Dembitz moved to Louisville in 1853 and set up a practice. He got involved in politics, and was an early supporter of the Republican Party, serving as a delegate to the party’s 1860 national convention where he cast his vote in favor of Abraham Lincoln. Dembitz was a strong opponent of slavery and even translated Uncle Tom’s Cabin into German. In the 1880s, Dembitz served four years as the Louisville city attorney. Dembitz was also an intellectual, writing book reviews for the Nation magazine, in addition to several books on the law. He was very involved in Jewish affairs, translating the books of Exodus and Leviticus for a new translation of the bible published by the Jewish Publication Society. He also wrote several articles for the 1903 Jewish Encyclopedia. Dembitz shares the unusual distinction of helping to establish both the Reform and Conservative movements. He was one of the founders of Hebrew Union College and was an early executive board member of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations. Dembitz broke with the Reform movement after the 1885 Pittsburg Platform, and later helped to establish the Conservative Jewish Theological Seminary.

Perhaps the most notable Jewish lawyer in Louisville was Louis Dembitz. Born in Posen, Dembitz came to the United States in 1849. After training in the law in Cincinnati, Dembitz moved to Louisville in 1853 and set up a practice. He got involved in politics, and was an early supporter of the Republican Party, serving as a delegate to the party’s 1860 national convention where he cast his vote in favor of Abraham Lincoln. Dembitz was a strong opponent of slavery and even translated Uncle Tom’s Cabin into German. In the 1880s, Dembitz served four years as the Louisville city attorney. Dembitz was also an intellectual, writing book reviews for the Nation magazine, in addition to several books on the law. He was very involved in Jewish affairs, translating the books of Exodus and Leviticus for a new translation of the bible published by the Jewish Publication Society. He also wrote several articles for the 1903 Jewish Encyclopedia. Dembitz shares the unusual distinction of helping to establish both the Reform and Conservative movements. He was one of the founders of Hebrew Union College and was an early executive board member of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations. Dembitz broke with the Reform movement after the 1885 Pittsburg Platform, and later helped to establish the Conservative Jewish Theological Seminary.

Louis Brandeis

Louis Brandeis

The career of Louis Dembitz greatly inspired his nephew, Louis Brandeis, who followed in his uncle’s footsteps to become both a celebrated lawyer and leader of the national Jewish community. As an adult, Brandeis changed his middle name to Dembitz to honor his uncle. Brandeis was born and raised in Louisville to parents who had emigrated from Prague. He attended Harvard Law School, and remained in the northeast where he began his illustrious legal career. An important adviser to President Woodrow Wilson, Brandeis was appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1916, becoming the first Jew to serve on the nation’s highest court. Brandeis also became a leader of American Zionism, serving as president of the Zionist Organization of America. While Brandeis’ public career played out in larger northeastern cities, he always remained tied to the city of his birth. Based on his dying wishes, Brandeis’ cremated remains are buried beneath a portico of the University of Louisville Law School, which was named for Brandeis in 1997.

Another prominent Louisville Jewish family that went on to national fame and influence were the Flexners. Abraham Flexner, who was born in Louisville right after the Civil War, became a leading national educator. His Carnegie Foundation report on medical schools led to profound changes in how American doctors were trained. Later, he co-founded the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton University, which he headed from 1930 to 1939. Abraham’s brother Simon was a leading medical researcher who led the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research from 1901 to 1935. Their brother Bernard Flexman became a prominent New York lawyer and ardent Zionist, serving as counsel for the Zionist Delegation at the Paris Peace Conference after World War I. Later, Bernard was a founder of the Council on Foreign Relations.

Another prominent Louisville Jewish family that went on to national fame and influence were the Flexners. Abraham Flexner, who was born in Louisville right after the Civil War, became a leading national educator. His Carnegie Foundation report on medical schools led to profound changes in how American doctors were trained. Later, he co-founded the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton University, which he headed from 1930 to 1939. Abraham’s brother Simon was a leading medical researcher who led the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research from 1901 to 1935. Their brother Bernard Flexman became a prominent New York lawyer and ardent Zionist, serving as counsel for the Zionist Delegation at the Paris Peace Conference after World War I. Later, Bernard was a founder of the Council on Foreign Relations.

Jewish Organizations in Louisville

Louisville Jews have always been concerned about taking care of their community members. The first Jewish organization in the city was the Israelite Benevolent Society founded in 1832, and by the 1850s, there were various Jewish charitable groups in the city. By 1907, the list of these organizations included: the Hebrew Sheltering Society, the Grabfelder Circle of Benevolence, three chapters of the Hebrew Ladies’ Benevolent Society, a chapter of the National Council of Jewish Women, two chapters of the Hebrew Ladies Sewing Circle, the United Hebrew Relief Association, the Jewish Hospital Association, and the Widows & Orphans Society. In 1909, Louisville Jews established a Federation of Jewish Charities that brought together 11 local and four national charity organizations.

Louisville women established a chapter of the National Council of Jewish Women in 1895. This organization helped the larger Louisville community as well as its Jewish population. Initially, the group focused on helping the growing immigrant population in the city. They worked closely with Neighborhood House, a settlement house that helped to assimilate these newcomers. The NCJW offered English and cooking classes for immigrant women at the settlement. They also helped to found the city’s first free kindergarten, located at Neighborhood House. In 1914, the NCJW started a lunch program at a local public school where many of the students were children of poor Jewish immigrants; through the program, students were able to buy basic kosher meals for a penny. Later in the 1930s, the group created a New American committee, headed for many years by Selma Kling, that helped settle the 400 Jewish refugees who came to Louisville before the war. After the Holocaust, many survivors settled in Louisville. The NCJW focused on issues of poverty and education, supporting libraries across the state and giving cooking equipment to rural schools so they could serve hot lunches. In the 1960s, the NCJW was involved with Head Start in Louisville. Originally, most of the members of the NCJW came from the German, Reform segment of the Jewish community, including many members of Adath Israel, but over the course of the 20th century, its membership has expanded to include a cross-section of the community.

The growing numbers of poor immigrants in Louisville led a group of prominent Jewish businessmen to establish Jewish Hospital in 1903 to care for their health needs. The hospital was also designed as a home for Jewish doctors who were often not allowed to practice at the city’s other hospitals. Samuel Grabfelder was a major donor and the hospital’s original chairman and president. In 1918, I.W. and Bernard Bernheim donated $100,000 to help build a new facility for the hospital. Although the hospital has a kosher kitchen and mezuzot on every door, and has been supported financially by the local Jewish community, it has served primarily non-Jews. In 1944, 88% of its patients were not Jewish. The hospital later moved to the newly formed medical center and became affiliated with the University of Louisville Medical School. Today, Jewish Hospital is one of the largest hospitals in the city and is nationally recognized for its medical care.

Another significant Jewish institution in Louisville got its start in 1862, when a group of Jews created the Young Men’s Hebrew Association. The middle of the Civil War was not a good time to start a social and educational club, and the group soon became defunct. After several stalled attempts, the YMHA was finally incorporated in 1890. Soon the group had a building with a gym, ballroom, and theater. In 1915, the YMHA dedicated a new larger building in a ceremony featuring Louisville’s mayor and the lieutenant governor. In the 1920s, the YMHA offered social, athletic, and educational activities for its 1500 members. While the organization suffered during the Great Depression, almost closing in 1931, it was active during World War II, opening its gym as a weekend dormitory for Jewish soldiers stationed nearby. The YMHA sponsored Saturday night dances for the soldiers and served them breakfast and dinner on Sundays. In 1955, the YMHA followed Louisville’s Jewish population and built a new facility in the suburban east side of the city, changing its name to the Jewish Community Center. The JCC still serves the Louisville Jewish community today.

The growth of these Jewish communal organizations, and their continual fundraising campaigns, led to calls to coordinate their efforts. Led by Charles Morris, the city’s Jewish institutions created the Conference of Jewish Organizations, which led one major fundraising campaign each year and supported all of the affiliated groups. In 1971, the conference changed its name to the Jewish Community Federation of Louisville.

Louisville Jews have always been concerned about taking care of their community members. The first Jewish organization in the city was the Israelite Benevolent Society founded in 1832, and by the 1850s, there were various Jewish charitable groups in the city. By 1907, the list of these organizations included: the Hebrew Sheltering Society, the Grabfelder Circle of Benevolence, three chapters of the Hebrew Ladies’ Benevolent Society, a chapter of the National Council of Jewish Women, two chapters of the Hebrew Ladies Sewing Circle, the United Hebrew Relief Association, the Jewish Hospital Association, and the Widows & Orphans Society. In 1909, Louisville Jews established a Federation of Jewish Charities that brought together 11 local and four national charity organizations.

Louisville women established a chapter of the National Council of Jewish Women in 1895. This organization helped the larger Louisville community as well as its Jewish population. Initially, the group focused on helping the growing immigrant population in the city. They worked closely with Neighborhood House, a settlement house that helped to assimilate these newcomers. The NCJW offered English and cooking classes for immigrant women at the settlement. They also helped to found the city’s first free kindergarten, located at Neighborhood House. In 1914, the NCJW started a lunch program at a local public school where many of the students were children of poor Jewish immigrants; through the program, students were able to buy basic kosher meals for a penny. Later in the 1930s, the group created a New American committee, headed for many years by Selma Kling, that helped settle the 400 Jewish refugees who came to Louisville before the war. After the Holocaust, many survivors settled in Louisville. The NCJW focused on issues of poverty and education, supporting libraries across the state and giving cooking equipment to rural schools so they could serve hot lunches. In the 1960s, the NCJW was involved with Head Start in Louisville. Originally, most of the members of the NCJW came from the German, Reform segment of the Jewish community, including many members of Adath Israel, but over the course of the 20th century, its membership has expanded to include a cross-section of the community.

The growing numbers of poor immigrants in Louisville led a group of prominent Jewish businessmen to establish Jewish Hospital in 1903 to care for their health needs. The hospital was also designed as a home for Jewish doctors who were often not allowed to practice at the city’s other hospitals. Samuel Grabfelder was a major donor and the hospital’s original chairman and president. In 1918, I.W. and Bernard Bernheim donated $100,000 to help build a new facility for the hospital. Although the hospital has a kosher kitchen and mezuzot on every door, and has been supported financially by the local Jewish community, it has served primarily non-Jews. In 1944, 88% of its patients were not Jewish. The hospital later moved to the newly formed medical center and became affiliated with the University of Louisville Medical School. Today, Jewish Hospital is one of the largest hospitals in the city and is nationally recognized for its medical care.

Another significant Jewish institution in Louisville got its start in 1862, when a group of Jews created the Young Men’s Hebrew Association. The middle of the Civil War was not a good time to start a social and educational club, and the group soon became defunct. After several stalled attempts, the YMHA was finally incorporated in 1890. Soon the group had a building with a gym, ballroom, and theater. In 1915, the YMHA dedicated a new larger building in a ceremony featuring Louisville’s mayor and the lieutenant governor. In the 1920s, the YMHA offered social, athletic, and educational activities for its 1500 members. While the organization suffered during the Great Depression, almost closing in 1931, it was active during World War II, opening its gym as a weekend dormitory for Jewish soldiers stationed nearby. The YMHA sponsored Saturday night dances for the soldiers and served them breakfast and dinner on Sundays. In 1955, the YMHA followed Louisville’s Jewish population and built a new facility in the suburban east side of the city, changing its name to the Jewish Community Center. The JCC still serves the Louisville Jewish community today.

The growth of these Jewish communal organizations, and their continual fundraising campaigns, led to calls to coordinate their efforts. Led by Charles Morris, the city’s Jewish institutions created the Conference of Jewish Organizations, which led one major fundraising campaign each year and supported all of the affiliated groups. In 1971, the conference changed its name to the Jewish Community Federation of Louisville.

Jewish Education

Another major concern of the Louisville Jewish community was the education of the next generation of Jews. Soon after Adath Israel was founded in the 1840s, the congregation established a short-lived day school for their children. When Rabbi Zarchy arrived in Louisville to lead the city’s Orthodox community in 1903, he started a Talmud Torah school. Five years later, local Jews founded the Louisville Hebrew School, which taught Judaism and the Hebrew language to male and female students for 90 minutes a day in the afternoons after school. By 1910, the Hebrew School had moved into its own $50,000 building, reflecting the importance the Jewish community put on education. While most of its students came from the Orthodox congregations, it also attracted a significant number of children from the Reform and Conservative congregations. The Louisville Hebrew School suffered when many of the congregations established their own religious schools; for a time, there was a local tax imposed on kosher meat and chickens to help support the school. The Louisville Hebrew School persevered though, moving to the new JCC building in 1955. It is now known as Louisville Beit Sefer Yachad (LBSY).

In 1948, the Council of Jewish Organizations tried to better organize Jewish education in the city, establishing the Bureau of Jewish Education. The bureau was tasked with running the Louisville Hebrew School, training congregational religious school teachers, and developing adult education and Jewish cultural programs. All seven of the city’s congregations worked with the bureau, which was aiming to raise the level of Jewish education in the city. Those who wanted a more intensive religious education for their children established the Eliahu Academy, a Jewish day school catering to the city’s Orthodox community, in 1953. While the school started slowly, it grew steadily, and even attracted students from the city’s Conservative and Reform congregations.

Another major concern of the Louisville Jewish community was the education of the next generation of Jews. Soon after Adath Israel was founded in the 1840s, the congregation established a short-lived day school for their children. When Rabbi Zarchy arrived in Louisville to lead the city’s Orthodox community in 1903, he started a Talmud Torah school. Five years later, local Jews founded the Louisville Hebrew School, which taught Judaism and the Hebrew language to male and female students for 90 minutes a day in the afternoons after school. By 1910, the Hebrew School had moved into its own $50,000 building, reflecting the importance the Jewish community put on education. While most of its students came from the Orthodox congregations, it also attracted a significant number of children from the Reform and Conservative congregations. The Louisville Hebrew School suffered when many of the congregations established their own religious schools; for a time, there was a local tax imposed on kosher meat and chickens to help support the school. The Louisville Hebrew School persevered though, moving to the new JCC building in 1955. It is now known as Louisville Beit Sefer Yachad (LBSY).

In 1948, the Council of Jewish Organizations tried to better organize Jewish education in the city, establishing the Bureau of Jewish Education. The bureau was tasked with running the Louisville Hebrew School, training congregational religious school teachers, and developing adult education and Jewish cultural programs. All seven of the city’s congregations worked with the bureau, which was aiming to raise the level of Jewish education in the city. Those who wanted a more intensive religious education for their children established the Eliahu Academy, a Jewish day school catering to the city’s Orthodox community, in 1953. While the school started slowly, it grew steadily, and even attracted students from the city’s Conservative and Reform congregations.

Jerry Abramson

Jerry Abramson

Louisville Jews in Politics

At the turn of the 21st century, the best known Jew in Louisville was longtime mayor Jerry Abramson. Abramson followed in a long history of Jewish political involvement in Louisville; from the late 19th century on, Louisville Jews have been active in local politics, with several serving on the city council or in the state legislature. Early Jewish resident Dann Byck served as president of the Board of AldermanAbramson was the first Jewish mayor of Louisville when he was elected in 1986. He had earlier served on the Board of Aldermen and had been appointed General Counsel to Governor John Brown. Abramson served as Louisville’s mayor until 1999, when term limits prevented him from running again. After Louisville formed a new consolidated metropolitan government, Abramson ran again in 2002, winning 74% of the vote; he was easily re-elected four years later. After becoming the longest serving mayor in Louisville history, Abramson was elected Lieutenant Governor of Kentucky in 2011, and was appointed to the position of Deputy Assistant to the President and White House Director of Intergovernmental Affairs in 2014.

Other Louisville Jews have been involved in politics in recent years. Since 2007, Louisville has been represented in the U.S. House of Representatives by John Yarmuth.

At the turn of the 21st century, the best known Jew in Louisville was longtime mayor Jerry Abramson. Abramson followed in a long history of Jewish political involvement in Louisville; from the late 19th century on, Louisville Jews have been active in local politics, with several serving on the city council or in the state legislature. Early Jewish resident Dann Byck served as president of the Board of AldermanAbramson was the first Jewish mayor of Louisville when he was elected in 1986. He had earlier served on the Board of Aldermen and had been appointed General Counsel to Governor John Brown. Abramson served as Louisville’s mayor until 1999, when term limits prevented him from running again. After Louisville formed a new consolidated metropolitan government, Abramson ran again in 2002, winning 74% of the vote; he was easily re-elected four years later. After becoming the longest serving mayor in Louisville history, Abramson was elected Lieutenant Governor of Kentucky in 2011, and was appointed to the position of Deputy Assistant to the President and White House Director of Intergovernmental Affairs in 2014.

Other Louisville Jews have been involved in politics in recent years. Since 2007, Louisville has been represented in the U.S. House of Representatives by John Yarmuth.

Jewish Hospital today

Jewish Hospital today

Congregational Consolidation

If the Jewish community has thrived politically in recent decades, institutionally it has endured a period of consolidation. In 1971, Orthodox congregation Agudath Achim merged with Anshei Sfard after its membership had moved out of its west end neighborhood. The combined congregation had 300 members in 1980. In 1994, Keneseth Israel officially joined the Conservative Movement, though the congregation had not been strictly Orthodox since it instituted mixed gender seating in the 1950s. While Louisville once had as many as four Orthodox congregations, today it only has one, Anshei Sfard.

The city’s two Reform congregations also decided to consolidate. Adath Israel and B’rith Sholom had first discussed merging in 1960. B’rith Sholom was losing members and having financial problems while Adath Israel needed a new synagogue in the eastern suburbs, where most of its members lived. In 1976, the two congregations decided to unite, becoming known officially as Congregation Adath Israel B’rith Sholom, but more commonly referred to as The Temple. In 1980, the combined congregation, now numbering 880 families, dedicated a new synagogue on Highway 42 in the eastern part of Louisville. Some members did not like the new larger congregation and decided to establish the smaller Reform Temple Shalom in 1976. The fledgling group met initially at the JCC and later at a local college. By 1978, Temple Shalom was able to hire a full-time rabbi; in 1989, it moved into its own synagogue building.

If the Jewish community has thrived politically in recent decades, institutionally it has endured a period of consolidation. In 1971, Orthodox congregation Agudath Achim merged with Anshei Sfard after its membership had moved out of its west end neighborhood. The combined congregation had 300 members in 1980. In 1994, Keneseth Israel officially joined the Conservative Movement, though the congregation had not been strictly Orthodox since it instituted mixed gender seating in the 1950s. While Louisville once had as many as four Orthodox congregations, today it only has one, Anshei Sfard.

The city’s two Reform congregations also decided to consolidate. Adath Israel and B’rith Sholom had first discussed merging in 1960. B’rith Sholom was losing members and having financial problems while Adath Israel needed a new synagogue in the eastern suburbs, where most of its members lived. In 1976, the two congregations decided to unite, becoming known officially as Congregation Adath Israel B’rith Sholom, but more commonly referred to as The Temple. In 1980, the combined congregation, now numbering 880 families, dedicated a new synagogue on Highway 42 in the eastern part of Louisville. Some members did not like the new larger congregation and decided to establish the smaller Reform Temple Shalom in 1976. The fledgling group met initially at the JCC and later at a local college. By 1978, Temple Shalom was able to hire a full-time rabbi; in 1989, it moved into its own synagogue building.

The Jewish Community in Louisville Today

Anshei Sfard.

Anshei Sfard. Photo courtesy of Julian Preisler

A Jewish Federation study in 1991 found 8,500 Jews in Louisville; 40% were Reform, 38% were Conservative, while 14% were Orthodox. The synagogue affiliation rate was very high, with 77% of Louisville Jews belonging to one of the city’s five congregations. A 2006 study found the community in slight decline, with a total population of 8,300. Over a quarter of Louisville Jews are over 65 years of age. Increasingly, the young Jews raised in Louisville are moving away after college, settling in larger cities like Chicago, New York, Washington, and Atlanta. In 2008, the city’s Jewish community day school, the Eliahu Academy, closed its doors. Other Jewish institutions in Louisville have discussed mergers in recent years. The community shares a Hebrew school, Louisville Beit Sefer Yachad, to educate all of Louisville's Jewish children, regardless of denomination.While Louisville is still an economically vibrant city, it has not enjoyed the same sun belt boom experienced by places like Houston or Atlanta. While Louisville’s Jewish community might never again reach its peak of 13,800 Jews it enjoyed in 1937, it will continue to be a vibrant, diverse community.

Sources

Landau, Herman. Adath Israel: The Story of Jewish Community, 1981.