Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Clarksdale, Mississippi

Overview >> Mississippi >> Clarksdale

Historical Overview

|

Clarksdale, Mississippi, sits on the Little Sunflower River a few miles east of the Mississippi River. The seat of Coahoma County, Clarksdale emerged as a trading hub in the late 19th century and has long served as an important cultural center for the Mississippi Delta region. As a result, Clarksdale and Coahoma County provided fertile ground for the development of blues and other African American musical genres. A litany of famous musicians either have roots in the area or spent time there.

Jewish history in Clarksdale and surrounding towns dates to the arrival of German speaking Jews around 1870. Jewish organizational life began in the 1890s and continued to grow in the early 20th century. In the 1930s, the area’s Jewish population reached 400 individuals, and for a time Clarksdale boasted the largest Jewish community in the state. Although Jewish communal life remained vibrant into the 1970s, the Jewish population declined for the next few decades. In 2003 Clarksdale’s only Jewish congregation, Congregation Beth Israel, closed its synagogue. |

Early Jewish Settlers

Adolph Kerstine, an early Jewish settler in Coahoma County and Clarksdale. Courtesy of Margery Kerstine.

Adolph Kerstine, an early Jewish settler in Coahoma County and Clarksdale. Courtesy of Margery Kerstine.

Community histories sometimes cite 1894 as the year of arrival for the city’s first Jews, but Jewish settlers have lived in Coahoma County since at least the late 1860s. Several of these earliest Jewish migrants settled in Friar’s Point, north-northwest of Clarksdale (known at the time as Clarksville) along the Mississippi River. The first known birth of a Jewish child in Coahoma County occurred in 1868, when Julia Gensburger gave birth to a daughter, Sarah, in Friar’s Point. Another early arrival was Adolph Kerstine, who moved to the area in the 1870s. Three of Adolph Kerstine’s brothers also lived in the county at the time. Adolph eventually settled in Clarksdale, where he made a living in dry goods and real estate.

The Jewish population grew slowly in the ensuing decades, in part due to the transience of Jewish migrants. Of the four Kerstine brothers, only Adolph remained in the area as of 1900. They may have left in response to Yellow fever outbreaks in the 1870s and flooding in 1882, both of which inhibited the city’s development and, likely, Jewish settlement as well. Following the arrival of a Memphis-to-New Orleans rail line in 1884, however, Clarksdale grew more quickly. The town’s population more than doubled during the 1890s, reaching 1,773 residents by 1900. Migrating African Americans—many of them formerly enslaved—contributed to this population increase, as they sought to make a living in the area’s booming cotton economy. Enslaved African Americans had already made up a majority of the county population by 1860. From the 1880s onward, Black residents constituted a significant portion of Clarksdale residents as well.

Jewish occupational patterns in Clarksdale mirrored trends not only in other developing towns in the Mississippi Delta but also in new sites of Jewish migration throughout the world. Jewish settlers often began as peddlers before founding dry goods or other retail stores, and they served customers from town as well as the surrounding countryside. Jewish merchants like Adolph Kerstine purchased wares from wholesalers in Memphis and initially relied on riverboats to transport the merchandise south. As Jewish business owners became rooted in the small but growing town, they also became part of its civic life. Al Nachman, for example, served multiple terms as a town alderman and city clerk. He was also a member of the Elks club.

The Jewish population grew slowly in the ensuing decades, in part due to the transience of Jewish migrants. Of the four Kerstine brothers, only Adolph remained in the area as of 1900. They may have left in response to Yellow fever outbreaks in the 1870s and flooding in 1882, both of which inhibited the city’s development and, likely, Jewish settlement as well. Following the arrival of a Memphis-to-New Orleans rail line in 1884, however, Clarksdale grew more quickly. The town’s population more than doubled during the 1890s, reaching 1,773 residents by 1900. Migrating African Americans—many of them formerly enslaved—contributed to this population increase, as they sought to make a living in the area’s booming cotton economy. Enslaved African Americans had already made up a majority of the county population by 1860. From the 1880s onward, Black residents constituted a significant portion of Clarksdale residents as well.

Jewish occupational patterns in Clarksdale mirrored trends not only in other developing towns in the Mississippi Delta but also in new sites of Jewish migration throughout the world. Jewish settlers often began as peddlers before founding dry goods or other retail stores, and they served customers from town as well as the surrounding countryside. Jewish merchants like Adolph Kerstine purchased wares from wholesalers in Memphis and initially relied on riverboats to transport the merchandise south. As Jewish business owners became rooted in the small but growing town, they also became part of its civic life. Al Nachman, for example, served multiple terms as a town alderman and city clerk. He was also a member of the Elks club.

Organized Jewish Life

A. H. Freyman with young Clarksdale congregants, n.d.

A. H. Freyman with young Clarksdale congregants, n.d.

By 1896, enough Jews lived in Clarksdale and the surrounding area to hold religious services. That year, five Clarksdale Jewish families founded a congregation known as Kehilath Jacob. Some accounts state that they first met in the home of Max Kaufman, while other sources name the Knights of Pythias Hall as their first meeting space. Early worship services followed Orthodox practice. From 1906 to 1912 the congregation employed the unordained Russian immigrant Harry Lubchansky as their religious leader. Lubchansky was followed by A.H. Freyman, who served the congregation for the next 20 years. Freyman became a revered fixture in the larger Clarksdale community, offering financial and spiritual support to both Jews and non-Jews. In addition to conducting religious ceremonies, he served as the community’s shochet (kosher slaughterer). He also conducted a choir for the High Holidays.

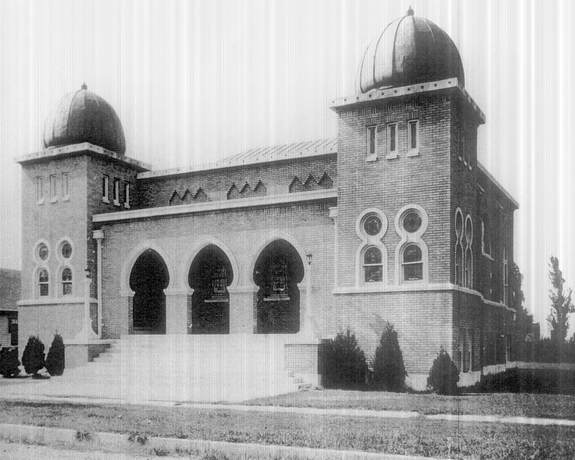

Kehilath Jacob continued to hold services in borrowed or rented spaces until 1910, when the congregation dedicated its first synagogue, a white stucco building at 69 Delta Avenue. With the erection of their first synagogue came a name change, and the congregation was known as Congregation Beth Israel from that point on. 1910 also marked the founding of a Clarksdale chapter of B’nai B’rith, an international fraternal and service organization for Jewish men.

In 1916 Congregation Beth Israel organized a religious school under the direction of Max Friedman. It boasted 50 students in its inaugural year. Local Jewish women founded the Ladies’ Aid Society in 1916 as well. The women’s group’s activities included fundraising for the congregation and hosting an annual New Year’s Ball for area Jews. The Ladies’ Aid Society was a forerunner to the congregation’s Temple Sisterhood and a local Hadassah chapter, both founded in the 1930s.

Kehilath Jacob continued to hold services in borrowed or rented spaces until 1910, when the congregation dedicated its first synagogue, a white stucco building at 69 Delta Avenue. With the erection of their first synagogue came a name change, and the congregation was known as Congregation Beth Israel from that point on. 1910 also marked the founding of a Clarksdale chapter of B’nai B’rith, an international fraternal and service organization for Jewish men.

In 1916 Congregation Beth Israel organized a religious school under the direction of Max Friedman. It boasted 50 students in its inaugural year. Local Jewish women founded the Ladies’ Aid Society in 1916 as well. The women’s group’s activities included fundraising for the congregation and hosting an annual New Year’s Ball for area Jews. The Ladies’ Aid Society was a forerunner to the congregation’s Temple Sisterhood and a local Hadassah chapter, both founded in the 1930s.

As of 1920, the local community consisted of approximately 40 Jewish families in Clarksdale, with additional congregants in outlying areas. Six Jewish families lived in Friar’s Point at the time, the small Mississippi River port that had attracted some of the area’s first Jewish settlers. Temple Beth Israel accommodated a variety of Jewish observances during its early decades, but younger members began to push for Reform services with more English prayers. The rift between Orthodox and Reform congregants threatened to split the congregation during the 1920s, until the construction of a new synagogue in 1929 allowed Temple Beth Israel to hold two concurrent services on separate floors. Ralph Lowitz served as cantor for the Orthodox services, which he led until his death in 1963.

Clarksdale Jews and Jim Crow Segregation

The emergence of Clarksdale’s Jewish community in the late 19th and early 20th centuries corresponded to the development of new system of racial segregation and white supremacy that was known as Jim Crow. In general, Jewish interactions with and reactions to racial hierarchies in Clarksdale and Coahoma County reflected trends elsewhere in the Mississippi Delta and in the South. European Jews and their descendants faced some social barriers but generally enjoyed the legal and economic privileges associated with whiteness, and although they occasionally tested some norms of anti-Black racism they most often accepted and supported the status quo.

Dry goods merchant Abe Isaacson, who settled in Clarksdale around 1910, illustrated Jewish relationships to race and racism in memoirs that he wrote decades later. He noted, for example, that Jewish, Greek, Syrian, Italian, and Chinese immigrants and their descendants clustered in various retail trades, while the wealthy white people—“real Southerners,” in Isaacson’s words—made their livings as landowners or in the professions. This white elite occupied a distinct class and had limited social contact with the “foreign element.” Despite this, Isaacson reported very little anti-Semitism in the South compared with the North. So long as Jews and other immigrant groups abided by the prevailing systems of race and class, they enjoyed tolerance and even support. During construction of the first local synagogue in 1910, according to Isaacson, the sheriff even donated “several weeks” of prison labor to the project (almost certainly provided by incarcerated Black men). Even limited acceptance by white Christians, in other words, allowed Jews to benefit from white supremacy and Jim Crow segregation. Consequently, local Jews often adopted elements of white thinking on race, as Isaacson demonstrated in his memoirs by parroting racist tropes in his assessment of African American life and the possibility of Black equality.

While Jewish individuals and institutions did benefit from white supremacy, Jews were sometimes viewed more positively than other white people by the Black community. Isaacson and others note, for example, that Black customers in small towns often preferred to shop at stores owned by Jews and other immigrant groups. He also mentions an instance in which an African American man had been sentenced to death and requested a visitation from Congregation Beth Israel’s Rabbi Tolochko prior to his execution. The inmate’s desire to speak with the rabbi indicated respect, and the rabbi’s acceptance of his invitation reflected a level of racial liberalism that other white clergy may not have shown.

Dry goods merchant Abe Isaacson, who settled in Clarksdale around 1910, illustrated Jewish relationships to race and racism in memoirs that he wrote decades later. He noted, for example, that Jewish, Greek, Syrian, Italian, and Chinese immigrants and their descendants clustered in various retail trades, while the wealthy white people—“real Southerners,” in Isaacson’s words—made their livings as landowners or in the professions. This white elite occupied a distinct class and had limited social contact with the “foreign element.” Despite this, Isaacson reported very little anti-Semitism in the South compared with the North. So long as Jews and other immigrant groups abided by the prevailing systems of race and class, they enjoyed tolerance and even support. During construction of the first local synagogue in 1910, according to Isaacson, the sheriff even donated “several weeks” of prison labor to the project (almost certainly provided by incarcerated Black men). Even limited acceptance by white Christians, in other words, allowed Jews to benefit from white supremacy and Jim Crow segregation. Consequently, local Jews often adopted elements of white thinking on race, as Isaacson demonstrated in his memoirs by parroting racist tropes in his assessment of African American life and the possibility of Black equality.

While Jewish individuals and institutions did benefit from white supremacy, Jews were sometimes viewed more positively than other white people by the Black community. Isaacson and others note, for example, that Black customers in small towns often preferred to shop at stores owned by Jews and other immigrant groups. He also mentions an instance in which an African American man had been sentenced to death and requested a visitation from Congregation Beth Israel’s Rabbi Tolochko prior to his execution. The inmate’s desire to speak with the rabbi indicated respect, and the rabbi’s acceptance of his invitation reflected a level of racial liberalism that other white clergy may not have shown.

Business and Civic Life

As the 20th century progressed, Jewish shops remained a visible presence in downtown Clarksdale. Of fifteen dry goods stores listed in Clarksdale’s 1916 city directory, at least two-thirds belonged to Jewish merchants. Other Jewish retail businesses included “general goods” and grocery stores, as well as later department stores. There were also Jews who moved from peddling and retail into other economic spheres in the early 20th century. Jake Fink used earnings from a store to purchase a plantation and later helped open a cotton gin in Duncan, southwest of Clarksdale. Herman Dansker became a “leading citizen” in Clarksdale after founding a seed and farm supply store. He was also known as an advocate for improved agricultural practices, such as skip-row planting for cotton. Outside of retail, Jewish businesses included the Sanitary Cafe, a restaurant owned by Ruben and Esther Dinner. They served gefilte fish under the name "Good Luck Fish Balls," and the restaurant's motto was “eat dinner with the Dinners.”

Jewish businesses became somewhat more specialized around 1920, with Jewish families involved in haberdasheries, jewelry stores, grocery stores, and tailor shops. The locations of Jewish stores also shifted in that decade, as new businesses sprung up along Issaquena Avenue, a few blocks from the original shopping district on Front Street (now Sunflower Avenue). While a majority of the Clarksdale Jewish community lived and worked in town, some members owned businesses in outlying areas. The Lovitz family, for example, owned a department store in Webb, where they were one of a few Jewish families in a 500-person town. Aaron Kline operated his dry goods store, called The Whale Store, in the small town of Alligator.

Jewish businesses became somewhat more specialized around 1920, with Jewish families involved in haberdasheries, jewelry stores, grocery stores, and tailor shops. The locations of Jewish stores also shifted in that decade, as new businesses sprung up along Issaquena Avenue, a few blocks from the original shopping district on Front Street (now Sunflower Avenue). While a majority of the Clarksdale Jewish community lived and worked in town, some members owned businesses in outlying areas. The Lovitz family, for example, owned a department store in Webb, where they were one of a few Jewish families in a 500-person town. Aaron Kline operated his dry goods store, called The Whale Store, in the small town of Alligator.

Rabbinical Leadership

The arrival of Rabbi Jerome Gerson Tolochko in 1932 marked a turning point for Beth Israel. Not only was Rabbi Tolochko the congregation’s first formally ordained resident rabbi, but his training at Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati reflected the Jewish community’s movement toward Reform Judaism.

Early in his career, Tolochko started a teachers’ training institute for Sunday school teachers, using his own published textbooks to raise the level of Jewish education in the state. In 1938, he created the Mississippi Institute of Jewish and Cognate Studies, a chartered institution with the authority to confer a bachelor’s degree in Jewish history and literature. Under Tolochko’s plan, religious school teachers received a bachelor’s degree through an extra year of training after completing the Jewish program of confirmation. In addition to serving as a source of education in Jewish history, Tolochko hoped that the institute would also build fellowship and understanding between Jews and non-Jews by stressing the similarities among all religions. The institute graduated ten students in 1938, and the plan was to expand the program through the creation of a bachelor’s program in comparative religion. Because of limited resources, however, the program was discontinued after a few years.

Throughout the 1940s, Clarksdale had a series of short term rabbis. It was not until about 1950 that a rabbi named Alexander Kline stayed for a long period of time. Rabbi Kline soon became well-known for his lectures on art history. His pursuits led him to a larger congregation in Lubbock, Texas, however.

Early in his career, Tolochko started a teachers’ training institute for Sunday school teachers, using his own published textbooks to raise the level of Jewish education in the state. In 1938, he created the Mississippi Institute of Jewish and Cognate Studies, a chartered institution with the authority to confer a bachelor’s degree in Jewish history and literature. Under Tolochko’s plan, religious school teachers received a bachelor’s degree through an extra year of training after completing the Jewish program of confirmation. In addition to serving as a source of education in Jewish history, Tolochko hoped that the institute would also build fellowship and understanding between Jews and non-Jews by stressing the similarities among all religions. The institute graduated ten students in 1938, and the plan was to expand the program through the creation of a bachelor’s program in comparative religion. Because of limited resources, however, the program was discontinued after a few years.

Throughout the 1940s, Clarksdale had a series of short term rabbis. It was not until about 1950 that a rabbi named Alexander Kline stayed for a long period of time. Rabbi Kline soon became well-known for his lectures on art history. His pursuits led him to a larger congregation in Lubbock, Texas, however.

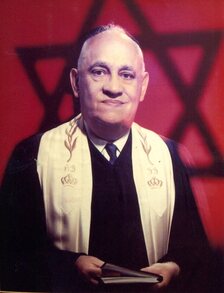

Rabbi Benjamin Schultz

Rabbi Benjamin Schultz

In 1962 Congregation Beth Israel hired Rabbi Benjamin Schultz, a controversial figure in the rabbinical world. He had previously served as chairman of the Jewish Anti-Communist League in New York and had accused prominent religious leaders—including his own former teacher, Rabbi Stephen S. Wise—of being controlled by Communists. Like other ardent anti-Communists, Schultz attacked the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s as a Communist plot to destabilize America. While Schultz’s attacks on mainstream Jewish luminaries and his association with McCarthyite anti-Communism made him an unattractive job candidate for most northern congregations, Clarksdale Jews were glad to hire a rabbi who disapproved of Civil Rights activism and would not challenge the status quo of segregation. While Schultz later claimed that he was not personally in favor of segregation, his public assertion that America needed “more Mississippi, not less” and his support for “states’ rights” made him popular with the Citizens’ Council and other segregationists. Schultz continued to lead services in Clarksdale until his death in 1978, and he was buried at the Beth Israel Cemetery.

Change and Decline

Clarksdale was home to nearly 300 Jewish residents at the end of World War II . In the postwar decades, Jews continued to operate a variety of retail businesses, including stores for dry goods, farm supplies, and hardware. Families like the Binders also owned farms in the country, often in addition to other sources of income.

In 1970 Congregation Beth Israel still claimed 100 families, but a series of economic changes had begun to have a visible effect on the Jewish community. The agricultural labor force in the Mississippi Delta had declined in preceding decades, as a consequence of New Deal programs that paid landowners to reduce crop production and the introduction of mechanical cotton pickers in 1947. As the number of sharecroppers and other agricultural workers decreased, so too did the customer base for many Jewish retail stores. The new generation of Jewish adults included doctors and lawyers (such as physicians Julius Levy and Melvin Ehrich) in addition to planters and merchants.

During the late 20th century, the rise of chain discount stores accelerated the decline of Jewish retail businesses, and Clarksdale’s Jewish population continued to shrink. Despite these trends, Congregation Beth Israel persisted in offering regular services and other activities with the help of visiting student rabbis from Hebrew Union College. Many members relocated to Memphis but continued to support the Clarksdale congregation and maintained ties to the Clarksdale community.

In 1970 Congregation Beth Israel still claimed 100 families, but a series of economic changes had begun to have a visible effect on the Jewish community. The agricultural labor force in the Mississippi Delta had declined in preceding decades, as a consequence of New Deal programs that paid landowners to reduce crop production and the introduction of mechanical cotton pickers in 1947. As the number of sharecroppers and other agricultural workers decreased, so too did the customer base for many Jewish retail stores. The new generation of Jewish adults included doctors and lawyers (such as physicians Julius Levy and Melvin Ehrich) in addition to planters and merchants.

During the late 20th century, the rise of chain discount stores accelerated the decline of Jewish retail businesses, and Clarksdale’s Jewish population continued to shrink. Despite these trends, Congregation Beth Israel persisted in offering regular services and other activities with the help of visiting student rabbis from Hebrew Union College. Many members relocated to Memphis but continued to support the Clarksdale congregation and maintained ties to the Clarksdale community.

The 21st Century

In the early 21st century, Beth Israel’s remaining 20 members decided they could no longer sustain a congregation. They made plans to close the synagogue and organized a deconsecration service on May 3, 2003. Student Rabbi Jennifer Tisdale led the final service, which featured stories and songs from the past. The event also served as a homecoming for former congregants who returned to Clarksdale for the occasion. Members, former members, and guests filled the sanctuary to capacity, evoking earlier decades when members brought their own chairs to overflowing High Holiday services.

In the wake of its closure, Beth Israel passed on its Torah scrolls and other Judaica. One Torah scroll found a new home at Camp Blue Star in Hendersonville, NC; another traveled to a new congregation forming in Poland. The building was ultimately sold, leaving the Jewish cemetery as the landmark that most explicitly testifies to the existence of a once vibrant Jewish community. The decline and demise of Jewish congregational life in Clarksdale did not signal the complete absence of Jewish residents, however. As of 2020 one young family calls Clarksdale home, and their two children attend religious school at Hebrew Union Congregation in Greenville.

In the wake of its closure, Beth Israel passed on its Torah scrolls and other Judaica. One Torah scroll found a new home at Camp Blue Star in Hendersonville, NC; another traveled to a new congregation forming in Poland. The building was ultimately sold, leaving the Jewish cemetery as the landmark that most explicitly testifies to the existence of a once vibrant Jewish community. The decline and demise of Jewish congregational life in Clarksdale did not signal the complete absence of Jewish residents, however. As of 2020 one young family calls Clarksdale home, and their two children attend religious school at Hebrew Union Congregation in Greenville.

Selected Bibliography

James C. Cobb, The Most Southern Place on Earth (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992).

Marcie Cohen Ferris, Matzoh Ball Gumbo: Culinary Tales of the Jewish South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005).

Abe Isaacson, From the Russian Ghetto to the Mississippi Delta, (c. 1940s), typewritten manuscript, Carnegie Public Library of Clarksdale and Coahoma County.

Allen Krause, “Rabbi Benjamin Schultz and the American Jewish League Against Communism,” Southern Jewish History, vol. 13, pp. 153-213, 2010.

Margery Kerstine, Merchants on Issaquena (Kerstine’s enterprises, 2020).

Margery Kerstine, Jewish Families of Coahoma County, online resources at link with published format forthcoming in late 2020.

Clive Webb, Fight Against Fear: Southern Jews and Black Civil Rights (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2003).

James C. Cobb, The Most Southern Place on Earth (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992).

Marcie Cohen Ferris, Matzoh Ball Gumbo: Culinary Tales of the Jewish South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005).

Abe Isaacson, From the Russian Ghetto to the Mississippi Delta, (c. 1940s), typewritten manuscript, Carnegie Public Library of Clarksdale and Coahoma County.

Allen Krause, “Rabbi Benjamin Schultz and the American Jewish League Against Communism,” Southern Jewish History, vol. 13, pp. 153-213, 2010.

Margery Kerstine, Merchants on Issaquena (Kerstine’s enterprises, 2020).

Margery Kerstine, Jewish Families of Coahoma County, online resources at link with published format forthcoming in late 2020.

Clive Webb, Fight Against Fear: Southern Jews and Black Civil Rights (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2003).