Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Memphis, Tennessee

Memphis: Historical Overview

|

Founded in 1819 along the banks of the Mississippi River, Memphis quickly grew as the river emerged as the economic backbone of the burgeoning nation. Named for the ancient capital of Egypt, Memphis became a river trading center for cotton and lumber. With its busy port, Memphis flourished in the decades before the Civil War and offered tremendous opportunity for newly arriving Jewish immigrants from central Europe. Between 1850 and 1860, the city’s population grew from 8,841 to 22,623 residents.

The Jewish community in Memphis would eventually grow to be the largest in Tennessee, and is still going strong today. |

Stories of the Jewish Community in Memphis

Early Settlers

The first known Jew to settle in Memphis was David Hart, who opened an inn and saloon in the booming market town by 1843. Sometime in the 1850s, Hart left Memphis. Joseph Andrews was another early Jewish settler, moving from Charleston, South Carolina, in 1840, where he had married into Haym Solomon’s family. Andrews was a successful merchant and cotton broker, and served as a city alderman in 1847-48. Joseph was instrumental in creating the first Jewish institutions in the city when he donated land for a Jewish cemetery after his brother Samuel died in 1847. This donation led to the creation of a Hebrew Benevolent Society to administer the cemetery and take care of local Jews in need. Out of this burial society emerged the city’s first Jewish congregation.

In the mid-19th century, a growing number of Jews from the German states made their way to Memphis from places like New Orleans, St. Louis, and Cincinnati. Often arriving as peddlers, many of these immigrants established successful retail businesses in the years before the Civil War. After his trans-Atlantic voyage, Benedict Lowenstein disembarked in New Orleans in 1854 and began to peddle up the Mississippi River. By 1855, he had reached Memphis and decided to settle. He opened a store, which soon flourished and expanded. He brought over three of his brothers from Europe, and changed the name of the store to B. Lowenstein and Brothers, which became one of the largest dry goods stores and wholesale suppliers in Memphis. Many peddlers and small town store owners in the region received their merchandise from the Lowenstein brothers. After Benedict died, his brother Elias took over the business and became a respected leader of the local business community.

Isaac and Jacob Goldsmith opened a dry goods store in 1870 which grew into one of the largest department stores in the city. Goldsmiths was the first store in town to be organized by department and to have an escalator and a bargain basement. Although it was owned by Jews, Goldsmiths became known for their extravagant Christmas celebrations. Each year, Jacob Goldsmith would meet Santa Claus at the train station, and personally escort him to the store, where he would meet with children during the Christmas season. This annual tradition eventually grew into a Christmas parade sponsored by Goldsmiths. Jacob Goldsmith was active in civic life, serving on several bank boards and leading the Memphis Chamber of Commerce.

The Goldsmiths and Lowensteins reflected the quintessential Southern Jewish success story. Yet as the story of Henry Seesel shows, the path toward economic prosperity was not often simple or straight forward. Seesel came to the United States from Bavaria in 1842. He first settled in Mississippi, where he peddled around Natchez and Vicksburg. After getting sick, he decided to move north to Cincinnati, where he worked for several months as a trunk maker. He later moved to Lexington, Kentucky, to work as a store clerk and then as a peddler in the area. After returning to Bavaria to check on his family and get married, Seesel settled in New Orleans in 1848. After peddling unsuccessfully in the city for three months, he moved back to Vicksburg where he bought a grocery store. This first store failed, and he returned to peddling in Mississippi and Louisiana. He then opened a store in Richmond, Louisiana, in 1853, but a flood washed away most of his customers’ farms, causing his business to fail. Henry then started a beef cattle business with his brother-in-law in Milliken’s Bend, Louisiana. In 1857, he decided to seek greater economic opportunity by moving to Memphis. After owning a beer saloon for 18 months, Seesel got back into the meat business. This last endeavor finally proved to be successful, as his butcher shop grew into a successful grocery store, and eventually a chain of grocery stores throughout Memphis. Seesel’s long and winding road to Memphis was fairly typical of Jewish immigrants, who often moved from town to town, and business to business, seeking financial success.

The first known Jew to settle in Memphis was David Hart, who opened an inn and saloon in the booming market town by 1843. Sometime in the 1850s, Hart left Memphis. Joseph Andrews was another early Jewish settler, moving from Charleston, South Carolina, in 1840, where he had married into Haym Solomon’s family. Andrews was a successful merchant and cotton broker, and served as a city alderman in 1847-48. Joseph was instrumental in creating the first Jewish institutions in the city when he donated land for a Jewish cemetery after his brother Samuel died in 1847. This donation led to the creation of a Hebrew Benevolent Society to administer the cemetery and take care of local Jews in need. Out of this burial society emerged the city’s first Jewish congregation.

In the mid-19th century, a growing number of Jews from the German states made their way to Memphis from places like New Orleans, St. Louis, and Cincinnati. Often arriving as peddlers, many of these immigrants established successful retail businesses in the years before the Civil War. After his trans-Atlantic voyage, Benedict Lowenstein disembarked in New Orleans in 1854 and began to peddle up the Mississippi River. By 1855, he had reached Memphis and decided to settle. He opened a store, which soon flourished and expanded. He brought over three of his brothers from Europe, and changed the name of the store to B. Lowenstein and Brothers, which became one of the largest dry goods stores and wholesale suppliers in Memphis. Many peddlers and small town store owners in the region received their merchandise from the Lowenstein brothers. After Benedict died, his brother Elias took over the business and became a respected leader of the local business community.

Isaac and Jacob Goldsmith opened a dry goods store in 1870 which grew into one of the largest department stores in the city. Goldsmiths was the first store in town to be organized by department and to have an escalator and a bargain basement. Although it was owned by Jews, Goldsmiths became known for their extravagant Christmas celebrations. Each year, Jacob Goldsmith would meet Santa Claus at the train station, and personally escort him to the store, where he would meet with children during the Christmas season. This annual tradition eventually grew into a Christmas parade sponsored by Goldsmiths. Jacob Goldsmith was active in civic life, serving on several bank boards and leading the Memphis Chamber of Commerce.

The Goldsmiths and Lowensteins reflected the quintessential Southern Jewish success story. Yet as the story of Henry Seesel shows, the path toward economic prosperity was not often simple or straight forward. Seesel came to the United States from Bavaria in 1842. He first settled in Mississippi, where he peddled around Natchez and Vicksburg. After getting sick, he decided to move north to Cincinnati, where he worked for several months as a trunk maker. He later moved to Lexington, Kentucky, to work as a store clerk and then as a peddler in the area. After returning to Bavaria to check on his family and get married, Seesel settled in New Orleans in 1848. After peddling unsuccessfully in the city for three months, he moved back to Vicksburg where he bought a grocery store. This first store failed, and he returned to peddling in Mississippi and Louisiana. He then opened a store in Richmond, Louisiana, in 1853, but a flood washed away most of his customers’ farms, causing his business to fail. Henry then started a beef cattle business with his brother-in-law in Milliken’s Bend, Louisiana. In 1857, he decided to seek greater economic opportunity by moving to Memphis. After owning a beer saloon for 18 months, Seesel got back into the meat business. This last endeavor finally proved to be successful, as his butcher shop grew into a successful grocery store, and eventually a chain of grocery stores throughout Memphis. Seesel’s long and winding road to Memphis was fairly typical of Jewish immigrants, who often moved from town to town, and business to business, seeking financial success.

Organized Jewish Life in Memphis

By the early 1850s, enough Jews lived in Memphis to begin establishing Jewish institutions. The Hebrew Benevolent Society was the first such organization, and its members soon began to worship together. In 1853, they established the congregation B’nai Israel. By 1858, they had acquired a former bank to use as their first synagogue. Right after the dedication of B’nai Israel’s temple, a group of 30 Jewish men established a B’nai B’rith chapter in Memphis. Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, who was in Memphis to officiate at the synagogue dedication, attended the meeting and encouraged the group to form a chapter of the organization, which offered sickness and death benefits to its members. In 1868, Memphis Jews created the United Hebrew Relief Association, which offered charity to Jews in need. Memphis Jews also established a social club, expressing their loyalty to their new home by naming it “the Southern Club,” although its name was changed to the “Memphis Club” during the Union’s wartime occupation of the city.

By the early 1850s, enough Jews lived in Memphis to begin establishing Jewish institutions. The Hebrew Benevolent Society was the first such organization, and its members soon began to worship together. In 1853, they established the congregation B’nai Israel. By 1858, they had acquired a former bank to use as their first synagogue. Right after the dedication of B’nai Israel’s temple, a group of 30 Jewish men established a B’nai B’rith chapter in Memphis. Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, who was in Memphis to officiate at the synagogue dedication, attended the meeting and encouraged the group to form a chapter of the organization, which offered sickness and death benefits to its members. In 1868, Memphis Jews created the United Hebrew Relief Association, which offered charity to Jews in need. Memphis Jews also established a social club, expressing their loyalty to their new home by naming it “the Southern Club,” although its name was changed to the “Memphis Club” during the Union’s wartime occupation of the city.

The Civil War

The Civil War brought both hardship and opportunity to the Jews of Memphis. Although most Memphis Jews were relatively recent immigrants, they supported the secessionist cause of their adopted homeland. Rabbi Simon Tuska of B’nai Israel attacked abolitionism and defended secession as the only means to support Southern rights. Many Memphis Jews volunteered to fight for the Confederacy. Memphis was captured by the Union army in 1862 as part of a Northern campaign to control the Mississippi River. The occupation years were somewhat turbulent for Jews. Jewish merchants and cotton buyers in town were prohibited from trading with Confederate areas during the Union occupation, although many made significant profits breaking the Northern blockade.

It was this illicit trade, in which both Jewish and Gentile merchants were involved, that prompted General U.S. Grant to issue his infamous General Orders No. 11, which tried to expel all Jews from portions of Tennessee, Kentucky, and northern Mississippi. After protests from Jews around the country, President Lincoln soon rescinded these orders, earning the gratitude of Jews in Memphis. After Lincoln’s assassination, Memphis’ Jewish congregations took part in a local memorial service, and the city’s B’nai B’rith chapter marched in a funeral procession for the slain president, who had freed the slaves and conquered the Confederacy. When Grant ran for president in 1868, Memphis Jews held a rally denouncing the war hero as unfit for the job. These recent immigrants were not hesitant to express their political opinions, even when they clashed with those of the mainstream

The Civil War brought both hardship and opportunity to the Jews of Memphis. Although most Memphis Jews were relatively recent immigrants, they supported the secessionist cause of their adopted homeland. Rabbi Simon Tuska of B’nai Israel attacked abolitionism and defended secession as the only means to support Southern rights. Many Memphis Jews volunteered to fight for the Confederacy. Memphis was captured by the Union army in 1862 as part of a Northern campaign to control the Mississippi River. The occupation years were somewhat turbulent for Jews. Jewish merchants and cotton buyers in town were prohibited from trading with Confederate areas during the Union occupation, although many made significant profits breaking the Northern blockade.

It was this illicit trade, in which both Jewish and Gentile merchants were involved, that prompted General U.S. Grant to issue his infamous General Orders No. 11, which tried to expel all Jews from portions of Tennessee, Kentucky, and northern Mississippi. After protests from Jews around the country, President Lincoln soon rescinded these orders, earning the gratitude of Jews in Memphis. After Lincoln’s assassination, Memphis’ Jewish congregations took part in a local memorial service, and the city’s B’nai B’rith chapter marched in a funeral procession for the slain president, who had freed the slaves and conquered the Confederacy. When Grant ran for president in 1868, Memphis Jews held a rally denouncing the war hero as unfit for the job. These recent immigrants were not hesitant to express their political opinions, even when they clashed with those of the mainstream

Yellow Fever Epidemics

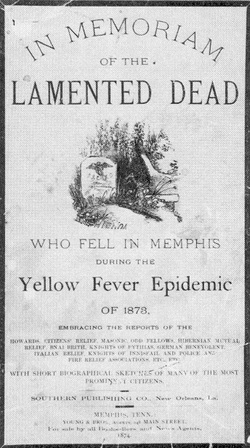

After the Civil War, the city grew along with its Jewish population, although the 1870s brought a series of yellow fever outbreaks that decimated the city and reshaped its Jewish community. This horrible disease had long been a scourge in the United States, especially in its port cities. As a trading port on the Mississippi River, Memphis experienced cholera and yellow fever outbreaks in the antebellum period. But nothing prepared them for the size and scope of the yellow fever epidemics of 1873 and 1878. In 1873, the disease spread upriver from New Orleans, killing 2,000 people in Memphis alone, including 94 Jews. But even this devastation paled in comparison to the outbreak five years later. In July of 1878, New Orleans saw the rise of cases of yellow fever and the disease soon worked its way northward. On August 23rd, Memphis officially declared an epidemic, though hundreds of residents had already died.

When the first cases were reported in Memphis, panic ensued, as people evacuated the city any way they could. Within three days, 20,000 white people had left, including most of its Jewish population. Jewish business owners closed their stores and left with their families as virtually all economic activity in the city ceased. Memphis had 45,000 people before the 1878 outbreak. Only 19,000 remained in the city during the epidemic, 5,000 of whom died. The plague ravaged throughout the extended hot summer of 1878, ending only with the first frost in the middle of October.

As merchants, most Jews had the economic means to flee the city, and the regional contacts to find a place for an extended stay. Certainly, kinship, religious, and economic ties with Jews in other cities helped them to evacuate Memphis. When Charles Wessolowsky, a regional organizer for the B’nai B’rith, traveled to St. Louis, he found many Jews from Memphis and Mississippi who had fled the yellow fever outbreak. Jews in St. Louis took in their refugee brethren. The local Young Men’s Hebrew Association held a fundraiser for the yellow fever sufferers of Memphis. Many Memphis Jews became a part of the community. A. Franklin, who had fled Memphis, became an active part of St. Louis’ Congregation Sheeres Israel, receiving a gold-headed cane from them in appreciation of his help leading services.

Several Memphis Jews belonged to the Howard Association, whose members were dedicated to staying in the city and aiding the victims of the disease. These included Rabbi Max Samfield (left), who remained in the city throughout the epidemics of 1873 and 1878. During the worst of the outbreak, Rabbi Samfield ministered to the sick, brought comfort to the bereaved, and buried the dead of all races and religions. David Gensburger, a city alderman, also stayed to help out. Such public service could be very risky. Nathan Mencken, a local store owner, sent his wife out of the city, and stayed to care for the sick. He later contracted the disease and died. Rabbi Ferdinand Sarner of the congregation Beth El Emeth also died from yellow fever. B’nai Israel buried 78 people in its cemetery that summer, including Theobold Folz, one its original founders. The epidemic left a number of Jewish orphans, who were served by orphanages in Cleveland and New Orleans.

The yellow fever outbreaks dealt the Jewish community a tremendous blow. Most of the Jews who fled the city in 1878 did not return. Memphis had 2,100 Jews before the outbreak, and only 300 after it was over. The city was in economic shambles, with the state revoking its charter and taking over management of the city for the next 14 years. Most Jewish merchants felt there was greater economic opportunity and less of a health risk elsewhere. B’nai Israel suffered a financial crisis due to a drop in membership, and was unable to pay its rabbi. Amazingly, considering the city’s devastation, the congregation soon rebounded, building a new synagogue by 1884.

After the Civil War, the city grew along with its Jewish population, although the 1870s brought a series of yellow fever outbreaks that decimated the city and reshaped its Jewish community. This horrible disease had long been a scourge in the United States, especially in its port cities. As a trading port on the Mississippi River, Memphis experienced cholera and yellow fever outbreaks in the antebellum period. But nothing prepared them for the size and scope of the yellow fever epidemics of 1873 and 1878. In 1873, the disease spread upriver from New Orleans, killing 2,000 people in Memphis alone, including 94 Jews. But even this devastation paled in comparison to the outbreak five years later. In July of 1878, New Orleans saw the rise of cases of yellow fever and the disease soon worked its way northward. On August 23rd, Memphis officially declared an epidemic, though hundreds of residents had already died.

When the first cases were reported in Memphis, panic ensued, as people evacuated the city any way they could. Within three days, 20,000 white people had left, including most of its Jewish population. Jewish business owners closed their stores and left with their families as virtually all economic activity in the city ceased. Memphis had 45,000 people before the 1878 outbreak. Only 19,000 remained in the city during the epidemic, 5,000 of whom died. The plague ravaged throughout the extended hot summer of 1878, ending only with the first frost in the middle of October.

As merchants, most Jews had the economic means to flee the city, and the regional contacts to find a place for an extended stay. Certainly, kinship, religious, and economic ties with Jews in other cities helped them to evacuate Memphis. When Charles Wessolowsky, a regional organizer for the B’nai B’rith, traveled to St. Louis, he found many Jews from Memphis and Mississippi who had fled the yellow fever outbreak. Jews in St. Louis took in their refugee brethren. The local Young Men’s Hebrew Association held a fundraiser for the yellow fever sufferers of Memphis. Many Memphis Jews became a part of the community. A. Franklin, who had fled Memphis, became an active part of St. Louis’ Congregation Sheeres Israel, receiving a gold-headed cane from them in appreciation of his help leading services.

Several Memphis Jews belonged to the Howard Association, whose members were dedicated to staying in the city and aiding the victims of the disease. These included Rabbi Max Samfield (left), who remained in the city throughout the epidemics of 1873 and 1878. During the worst of the outbreak, Rabbi Samfield ministered to the sick, brought comfort to the bereaved, and buried the dead of all races and religions. David Gensburger, a city alderman, also stayed to help out. Such public service could be very risky. Nathan Mencken, a local store owner, sent his wife out of the city, and stayed to care for the sick. He later contracted the disease and died. Rabbi Ferdinand Sarner of the congregation Beth El Emeth also died from yellow fever. B’nai Israel buried 78 people in its cemetery that summer, including Theobold Folz, one its original founders. The epidemic left a number of Jewish orphans, who were served by orphanages in Cleveland and New Orleans.

The yellow fever outbreaks dealt the Jewish community a tremendous blow. Most of the Jews who fled the city in 1878 did not return. Memphis had 2,100 Jews before the outbreak, and only 300 after it was over. The city was in economic shambles, with the state revoking its charter and taking over management of the city for the next 14 years. Most Jewish merchants felt there was greater economic opportunity and less of a health risk elsewhere. B’nai Israel suffered a financial crisis due to a drop in membership, and was unable to pay its rabbi. Amazingly, considering the city’s devastation, the congregation soon rebounded, building a new synagogue by 1884.

The Community Grows

An important part of the Jewish community’s resurgence after the yellow fever epidemics was the arrival of new immigrants from Eastern Europe. These Jewish immigrants settled into a Memphis neighborhood known as “the Pinch,” a 12-block area north of downtown. The Pinch became Memphis’ miniature version of New York City's Lower East Side. Many of the Eastern European Jews started out as peddlers, getting merchandise on credit from Jewish wholesalers in town. After some success, they would open small retail stores in the neighborhood, which soon became filled with kosher markets and delis.

Most of these new immigrants were more traditional in their worship and chose to found their own congregations rather than join the Reform B’nai Israel. Jews in the Pinch founded many small congregations, often based around their area of origin. There was a Lithuanian congregation, a Galician congregation, and several others. Many of these congregations did not last, often closing once their membership moved to other parts of the city, but two Orthodox synagogues managed to make the transition from the immigrant era. In 1884, Orthodox Jews formed the Baron Hirsch Benevolent Society, which has grown into one of the largest Orthodox congregations in the country. In 1893, Polish Jews founded Anshei Sphard, which still serves the Memphis Orthodox community today.

In addition to Orthodox religious practices, Eastern European Jews also brought over new political philosophies. The idea of a Jewish homeland was anathema to many German Jews who felt at home in America. But recent immigrants from Eastern Europe were drawn to the new Zionist movement, which worked for the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine. With Reform leaders like Rabbi Samfield opposed to the movement, it was left to Eastern European Jews to found the city’s first Zionist organization, Ahavath Zion, in 1896. One member of the society wrote a number of articles about Zionism for Memphis’ daily newspaper, the Commercial Appeal. Memphis Zionists were very active in the early years of the movement, raising $6000 for the cause in 1898. The group died out in the first decade of the 20th century, but was reorganized in 1912. Ahavath Zion held Sunday picnics and other activities to raise money for the Jewish National Fund, which purchased land in Palestine for Jewish settlement. In 1918, a chapter of Hadassah, the world’s leading Zionist organization for women, was founded in Memphis.

An important part of the Jewish community’s resurgence after the yellow fever epidemics was the arrival of new immigrants from Eastern Europe. These Jewish immigrants settled into a Memphis neighborhood known as “the Pinch,” a 12-block area north of downtown. The Pinch became Memphis’ miniature version of New York City's Lower East Side. Many of the Eastern European Jews started out as peddlers, getting merchandise on credit from Jewish wholesalers in town. After some success, they would open small retail stores in the neighborhood, which soon became filled with kosher markets and delis.

Most of these new immigrants were more traditional in their worship and chose to found their own congregations rather than join the Reform B’nai Israel. Jews in the Pinch founded many small congregations, often based around their area of origin. There was a Lithuanian congregation, a Galician congregation, and several others. Many of these congregations did not last, often closing once their membership moved to other parts of the city, but two Orthodox synagogues managed to make the transition from the immigrant era. In 1884, Orthodox Jews formed the Baron Hirsch Benevolent Society, which has grown into one of the largest Orthodox congregations in the country. In 1893, Polish Jews founded Anshei Sphard, which still serves the Memphis Orthodox community today.

In addition to Orthodox religious practices, Eastern European Jews also brought over new political philosophies. The idea of a Jewish homeland was anathema to many German Jews who felt at home in America. But recent immigrants from Eastern Europe were drawn to the new Zionist movement, which worked for the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine. With Reform leaders like Rabbi Samfield opposed to the movement, it was left to Eastern European Jews to found the city’s first Zionist organization, Ahavath Zion, in 1896. One member of the society wrote a number of articles about Zionism for Memphis’ daily newspaper, the Commercial Appeal. Memphis Zionists were very active in the early years of the movement, raising $6000 for the cause in 1898. The group died out in the first decade of the 20th century, but was reorganized in 1912. Ahavath Zion held Sunday picnics and other activities to raise money for the Jewish National Fund, which purchased land in Palestine for Jewish settlement. In 1918, a chapter of Hadassah, the world’s leading Zionist organization for women, was founded in Memphis.

Other Jews worked toward a more universalistic utopia, supporting the ideals of socialism. Memphis Jews established a branch of the Workmen’s Circle, a national Jewish organization that espoused socialism and Yiddish culture. In the northeast, the Workmen’s Circle was quite popular with Jewish workers in the needle trades. In Memphis, a Jewish working class did not exist, so most circle members were small store owners. They remained true to the ideals of the organization and often donated funds to striking workers around the country. Over time, the Memphis Workmen’s Circle became more of a social and cultural organization. They established a Yiddish school for children and acquired a clubhouse on the corner of Jefferson and Orleans streets. Some Memphis Jews were actively involved in the labor movement. Jake Cohen was president of the Tennessee Federation of Labor, and helped organize a massive Labor Day celebration in 1933 that drew over 20,000 workers in a parade down Main Street.

While groups like the Workmen’s Circle were dedicated to preserving the European cultural traditions that Jews brought with them, other Jewish organizations worked to assimilate the newcomers. German Jews created the “Jewish Neighborhood House” in 1901, a settlement house which offered programs to help the Pinch’s residents adjust to life in the United States. The Jewish Neighborhood House had a medical clinic to care for the area’s babies, and offered classes in hygiene, art, and English. It eventually became a community center for the neighborhood, with a free kindergarten and activities for children. German Jews also created the Federation of Jewish Charities in 1906 to help the growing number of Eastern European Jews settling in Memphis.

While groups like the Workmen’s Circle were dedicated to preserving the European cultural traditions that Jews brought with them, other Jewish organizations worked to assimilate the newcomers. German Jews created the “Jewish Neighborhood House” in 1901, a settlement house which offered programs to help the Pinch’s residents adjust to life in the United States. The Jewish Neighborhood House had a medical clinic to care for the area’s babies, and offered classes in hygiene, art, and English. It eventually became a community center for the neighborhood, with a free kindergarten and activities for children. German Jews also created the Federation of Jewish Charities in 1906 to help the growing number of Eastern European Jews settling in Memphis.

It did not take very long for many Pinch residents to follow in the footsteps of their German co-religionists and climb the economic and social ladder. Born in nearby Tupelo, Mississippi, Abe Plough grew up in the Pinch. As a teenager, he was drawn to the drug business, working in a local drug store. In 1908, he started the Plough Chemical Company in a room above his father’s store. Plough created an antiseptic healing oil that he claimed was “a sure cure for any ill of man or beast.” From this modest beginning, Plough built a business empire, which included drugs, cosmetics, and St. Joseph’s Aspirin. His company merged with Schering in 1971, forming one of the largest drug companies in the world.

Philip Belz came to Memphis from Russia in 1910 to join his father who had immigrated six years earlier. In 1935, Belz started a construction company that specialized in building inexpensive apartments, which eventually grew into a major real estate company. His son Jack joined him in the business, who continued to build Belz Enterprises. In 1975, Jack Belz bought and refurbished the quintessential Memphis landmark, the Peabody Hotel.

Philip Belz came to Memphis from Russia in 1910 to join his father who had immigrated six years earlier. In 1935, Belz started a construction company that specialized in building inexpensive apartments, which eventually grew into a major real estate company. His son Jack joined him in the business, who continued to build Belz Enterprises. In 1975, Jack Belz bought and refurbished the quintessential Memphis landmark, the Peabody Hotel.

Sam Cooper grew up poor in the Pinch. He was interested in business and got a job with the local Humko Corporation. Cooper rose in the company’s ranks and eventually served as its president for 24 years. Cooper became a major civic leader, working to keep St. Jude’s Hospital and the University of Tennessee Medical School in Memphis. He was also vice president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Memphis. When he presided at the bank’s dedication, he noted that its location was on the same spot his father’s tailor shop had once been. He received many awards for his local charity and civic work. In 1968, the city named a major boulevard after Cooper.

Political Engagement

In addition to playing a leading role in the city’s economic development, Memphis Jews were also closely involved in the city’s politics, which were dominated for over forty years by E.H. Crump, the “boss” of the Memphis political machine. Several Jews played important roles in Crump’s machine. Will Gerber grew up in the Pinch and became a successful lawyer, serving as city attorney from 1935 to 1942 and later as the attorney general of Shelby County, with Crump’s patronage. Gerber was a loyal supporter of the machine, and even physically attacked a New York Times reporter writing a story on local election irregularities at a polling precinct. Crump’s acceptance of Jews set a tolerant tone in the city; when the nativist Ku Klux Klan rose to national prominence in the 1920s, Crump’s opposition prevented them from becoming a force in Memphis. Several local Jews were elected to office. William Rosenfeld and Joseph Hanover served in the state legislature. Hanover led the floor fight to approve the women’s suffrage amendment.

Political Engagement

In addition to playing a leading role in the city’s economic development, Memphis Jews were also closely involved in the city’s politics, which were dominated for over forty years by E.H. Crump, the “boss” of the Memphis political machine. Several Jews played important roles in Crump’s machine. Will Gerber grew up in the Pinch and became a successful lawyer, serving as city attorney from 1935 to 1942 and later as the attorney general of Shelby County, with Crump’s patronage. Gerber was a loyal supporter of the machine, and even physically attacked a New York Times reporter writing a story on local election irregularities at a polling precinct. Crump’s acceptance of Jews set a tolerant tone in the city; when the nativist Ku Klux Klan rose to national prominence in the 1920s, Crump’s opposition prevented them from becoming a force in Memphis. Several local Jews were elected to office. William Rosenfeld and Joseph Hanover served in the state legislature. Hanover led the floor fight to approve the women’s suffrage amendment.

The JCC

Created in 1949, the JCC was a cooperative effort of the Orthodox and Reform communities to create a common social and cultural space. While some assimilated Reform Jews feared that the JCC was simply recreating a Jewish ghetto, and Orthodox Jews feared that it was not religious enough, most soon saw the benefits in building a stronger, more unified community.

Created in 1949, the JCC was a cooperative effort of the Orthodox and Reform communities to create a common social and cultural space. While some assimilated Reform Jews feared that the JCC was simply recreating a Jewish ghetto, and Orthodox Jews feared that it was not religious enough, most soon saw the benefits in building a stronger, more unified community.

The Civil Rights Movement

The pull between assimilation and preserving Jewish ideals can also be seen in the civil rights movement. Like Jews in other parts of the South, many Jewish Memphians accepted the ideology of white supremacy, which granted them the social and economic benefits of whiteness. But others, inspired by Jewish teachings and their own experience with anti-Semitism, worked for racial justice. During the pre-civil rights era, a number of Jews expressed support for black causes even though they did not challenge segregation directly. M.A. Lightman, the founder and president of the Malco Theater chain, headed a 1945 fundraising drive to expand and upgrade the city’s black hospital. Abe Scharff, owner of a successful dry cleaning company, donated a house for use as a YMCA for blacks. In 1947, Scharff donated $50,000 to build a new YMCA for blacks, which was named in his honor. Bert and David Bornblum, who owned a clothing store on Beale Street, were the first merchants on this busy commercial street to hire black salesmen. Josephine Burson planned a public reception for Lady Bird Johnson during the 1960 presidential campaign that she insisted be racially integrated; the reception was the first time the city auditorium had held an integrated event.

During the years of the civil rights movement, Jewish merchants were under pressure from activists to integrate their stores, and from segregationists to maintain white supremacy. In the 1960s, a handful of Jewish department store owners organized meetings with other merchants to discuss the peaceful integration of their stores. Jack Goldsmith, owner of Goldsmith’s, and Mel Grinspan of the Shainberg’s store chain, led this effort which was designed to have all the stores integrate together so none of them could be singled out for retribution. Both stores began to hire black sales clerks to ease this process. Grinspan also worked to integrate the Shainberg stores in Mississippi, which led to threats against him by the Ku Klux Klan. He later aided minority-owned businesses in Memphis.

Memphis rabbis had a long tradition of support for racial justice. Rabbi William Fineshriber of Temple Israel was an outspoken critic of lynching and the Ku Klux Klan during the 1910s and 1920s. During the 1960s, Rabbi Arie Becker, of the Conservative congregation Beth Shalom, often discussed civil rights during his sermons, which made many of his congregants uncomfortable. Becker, who had fled Europe before the Holocaust, was one of 19 Conservative rabbis who left a meeting of the Rabbinic Assembly in 1963 to fly down to Birmingham to march with Martin Luther King, Jr. When Rabbi Becker returned to Memphis, he received death threats, forcing his family to move to Philadelphia until things cooled off.

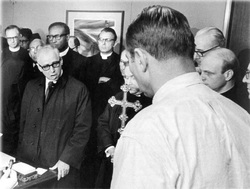

Rabbi James Wax of Temple Israel was also a strong voice in favor of civil rights. He was a board member of the Memphis Committee on Community Relations, a moderate group that pushed for peaceful integration in the early 1960s. Wax also got involved in the sanitation workers’ strike in 1968. It was during this prolonged dispute between the city and the largely black union that Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis. Rabbi Wax met with Mayor Henry Loeb to try to convince him to meet the striker’s demands and settle the strike. Loeb was a former congregant of Rabbi Wax and was twice mayor of Memphis. He was first elected in 1960. He was elected again in 1968, but soon after converted to Christianity when he married an Episcopalian woman. Rabbi Wax was initially unable to convince Mayor Loeb to settle the strike. After King’s assassination, Wax went back to the mayor with an interracial delegation of local ministers and demanded that the mayor “speak out at last in favor of human dignity.” Wax later helped to work out a solution which involved Abe Plough’s secretly donating money to the city to cover the cost of the pay increases, a central demand of the strikers.

The pull between assimilation and preserving Jewish ideals can also be seen in the civil rights movement. Like Jews in other parts of the South, many Jewish Memphians accepted the ideology of white supremacy, which granted them the social and economic benefits of whiteness. But others, inspired by Jewish teachings and their own experience with anti-Semitism, worked for racial justice. During the pre-civil rights era, a number of Jews expressed support for black causes even though they did not challenge segregation directly. M.A. Lightman, the founder and president of the Malco Theater chain, headed a 1945 fundraising drive to expand and upgrade the city’s black hospital. Abe Scharff, owner of a successful dry cleaning company, donated a house for use as a YMCA for blacks. In 1947, Scharff donated $50,000 to build a new YMCA for blacks, which was named in his honor. Bert and David Bornblum, who owned a clothing store on Beale Street, were the first merchants on this busy commercial street to hire black salesmen. Josephine Burson planned a public reception for Lady Bird Johnson during the 1960 presidential campaign that she insisted be racially integrated; the reception was the first time the city auditorium had held an integrated event.

During the years of the civil rights movement, Jewish merchants were under pressure from activists to integrate their stores, and from segregationists to maintain white supremacy. In the 1960s, a handful of Jewish department store owners organized meetings with other merchants to discuss the peaceful integration of their stores. Jack Goldsmith, owner of Goldsmith’s, and Mel Grinspan of the Shainberg’s store chain, led this effort which was designed to have all the stores integrate together so none of them could be singled out for retribution. Both stores began to hire black sales clerks to ease this process. Grinspan also worked to integrate the Shainberg stores in Mississippi, which led to threats against him by the Ku Klux Klan. He later aided minority-owned businesses in Memphis.

Memphis rabbis had a long tradition of support for racial justice. Rabbi William Fineshriber of Temple Israel was an outspoken critic of lynching and the Ku Klux Klan during the 1910s and 1920s. During the 1960s, Rabbi Arie Becker, of the Conservative congregation Beth Shalom, often discussed civil rights during his sermons, which made many of his congregants uncomfortable. Becker, who had fled Europe before the Holocaust, was one of 19 Conservative rabbis who left a meeting of the Rabbinic Assembly in 1963 to fly down to Birmingham to march with Martin Luther King, Jr. When Rabbi Becker returned to Memphis, he received death threats, forcing his family to move to Philadelphia until things cooled off.

Rabbi James Wax of Temple Israel was also a strong voice in favor of civil rights. He was a board member of the Memphis Committee on Community Relations, a moderate group that pushed for peaceful integration in the early 1960s. Wax also got involved in the sanitation workers’ strike in 1968. It was during this prolonged dispute between the city and the largely black union that Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis. Rabbi Wax met with Mayor Henry Loeb to try to convince him to meet the striker’s demands and settle the strike. Loeb was a former congregant of Rabbi Wax and was twice mayor of Memphis. He was first elected in 1960. He was elected again in 1968, but soon after converted to Christianity when he married an Episcopalian woman. Rabbi Wax was initially unable to convince Mayor Loeb to settle the strike. After King’s assassination, Wax went back to the mayor with an interracial delegation of local ministers and demanded that the mayor “speak out at last in favor of human dignity.” Wax later helped to work out a solution which involved Abe Plough’s secretly donating money to the city to cover the cost of the pay increases, a central demand of the strikers.

Civic Engagement

In addition to civil rights, Jews got involved with other social issues in Memphis. Myra Dreifus was a local activist who fought against hunger in her community. In 1964, she organized a group called “Food for Fitness” that lobbied the school board for free school lunches for poor children. She eventually convinced the county to levy a special tax to fund school lunches. After this success, the group, which had many Jewish members, changed its name to “Fund for Needy School Children.” Dreifus also convinced the city to fund a summer jobs program which she had set up for black kids in Memphis in 1968, which helped save the city from riots over the summer. Dreifus won a Humanitarian Award from the National Conference of Christians and Jews.

In addition to civil rights, Jews got involved with other social issues in Memphis. Myra Dreifus was a local activist who fought against hunger in her community. In 1964, she organized a group called “Food for Fitness” that lobbied the school board for free school lunches for poor children. She eventually convinced the county to levy a special tax to fund school lunches. After this success, the group, which had many Jewish members, changed its name to “Fund for Needy School Children.” Dreifus also convinced the city to fund a summer jobs program which she had set up for black kids in Memphis in 1968, which helped save the city from riots over the summer. Dreifus won a Humanitarian Award from the National Conference of Christians and Jews.

The Second Half of the 20th Century

The Jewish community grew tremendously in the years after World War II. In 1948, an estimated 6,500 Jews lived in Memphis. By 1960, this figure had grown to 9,000. The population remained at this plateau for the next few decades, though it has dropped slightly in recent years. In addition to population growth, the 1950s also saw the movement of Memphis Jews out to the eastern suburbs of the city. Following their membership, synagogues moved east as well. The Orthodox congregations moved first since they had to be within walking distance of their members. Anshe Sphard built a new synagogue in the eastern part of the city in 1950. Baron Hirsch built a large new synagogue in 1957, with a sanctuary that could seat over 2000 people, which showed the continuing strength of Orthodox Judaism in Memphis.

Baron Hirsch and Anshe Sphard remained Orthodox, so a small group of Memphis Jews established Beth Sholom, Memphis’ first Conservative congregation in 1954. Rabbi Wax of the Reform Temple Israel was very supportive of this new congregation, helping to raise money for it. Beth Shalom grew quickly and soon hired a rabbi and purchased a building in the eastern part of Memphis for use as a synagogue.

The Jewish community grew tremendously in the years after World War II. In 1948, an estimated 6,500 Jews lived in Memphis. By 1960, this figure had grown to 9,000. The population remained at this plateau for the next few decades, though it has dropped slightly in recent years. In addition to population growth, the 1950s also saw the movement of Memphis Jews out to the eastern suburbs of the city. Following their membership, synagogues moved east as well. The Orthodox congregations moved first since they had to be within walking distance of their members. Anshe Sphard built a new synagogue in the eastern part of the city in 1950. Baron Hirsch built a large new synagogue in 1957, with a sanctuary that could seat over 2000 people, which showed the continuing strength of Orthodox Judaism in Memphis.

Baron Hirsch and Anshe Sphard remained Orthodox, so a small group of Memphis Jews established Beth Sholom, Memphis’ first Conservative congregation in 1954. Rabbi Wax of the Reform Temple Israel was very supportive of this new congregation, helping to raise money for it. Beth Shalom grew quickly and soon hired a rabbi and purchased a building in the eastern part of Memphis for use as a synagogue.

The Jewish Community in Memphis Today

Over the last few decades, the Memphis Jewish community has shrunk slightly. A 2006 study estimated that 7,800 Jews lived in the Memphis metropolitan area, about equal to the Jewish population of Nashville. Memphis has always been the largest Jewish community in Tennessee, though it seems poised to hand this title over to the state’s capital.

Sources

Lewis, Selma S. A Biblical People in the Bible Belt: The Jewish Community of Memphis, Tennessee, 1840s-1960s. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 1998.