Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Temple Israel, Memphis, Tennessee

Photos Courtesy of the Temple Israel Archives

For over 150 years, Temple Israel has been a home for Reform Jews in Memphis. Growing from a small group of 36 members to a full-service congregation with 1800 families, Temple Israel has largely avoided the factionalism and schisms that have often struck large congregations around the country. Over the years, the congregation has been known by various names, including B’nai Israel, Children of Israel, and Temple Israel. Despite these different names, Temple Israel has always been the only Reform congregation in Memphis.

In 1850, Memphis’ small but growing Jewish community established the Hebrew Benevolent Society to oversee a new cemetery that had been donated by early Jewish settler Joseph Andrews. Four years later, its 36 members decided to form the city’s first Jewish congregation, B’nai Israel (Children of Israel). The fledging congregation received a windfall after the death of the reclusive Jewish philanthropist from New Orleans, Judah Touro, who left $2000 to the group in his will. In 1857, B’nai Israel rented a former bank building, and remodeled it into a synagogue. Three years later, they purchased the building.

In 1850, Memphis’ small but growing Jewish community established the Hebrew Benevolent Society to oversee a new cemetery that had been donated by early Jewish settler Joseph Andrews. Four years later, its 36 members decided to form the city’s first Jewish congregation, B’nai Israel (Children of Israel). The fledging congregation received a windfall after the death of the reclusive Jewish philanthropist from New Orleans, Judah Touro, who left $2000 to the group in his will. In 1857, B’nai Israel rented a former bank building, and remodeled it into a synagogue. Three years later, they purchased the building.

From their earliest years, the members were divided over the issue of observance. As recent immigrants from the German states, most members struggled with the question of how much to alter their traditional practices to fit their new environment. As the only Jewish congregation in Memphis, Jews had to work out their differences on this issue. When they were planning the remodeling of their synagogue, they debated whether to have a separate women’s gallery. By a vote of 18 to 14, the members decided to maintain the tradition of women sitting apart from men. Yet the future evolution of the congregation was foreshadowed when Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, the father of Reform Judaism in America, came down to lead the synagogue dedication ceremony on March 26, 1858. B’nai Israel advertised for a rabbi in Wise’s English-language newspaper, the American Israelite, calling for a “lecturer, reader and teacher to lecture in English and German, and to lead a choir.”

Despite this job description, which seemed to call for a Reform rabbi, the congregation still adhered to Orthodox Judaism. At the same time, they also advertised for a kosher butcher, or shochet. The rabbi they eventually hired was recommended by the prominent Orthodox rabbi Isaac Leeser of Philadelphia. Jacob Peres (left) served B’nai Israel as its first rabbi and worked to strengthen its adherence to Orthodoxy. Under his leadership, the congregation passed a new rule stating that only members who fully observed the Sabbath could receive Torah honors on the high holidays. That such a law was needed likely indicates that most members did not strictly observe the Sabbath. Ironically, Rabbi Peres himself soon got in trouble with the congregation over Sabbath observance. Peres owned a grocery store with his brother which remained open on Saturdays. In 1860, the congregation fired Peres over the issue.

Despite this job description, which seemed to call for a Reform rabbi, the congregation still adhered to Orthodox Judaism. At the same time, they also advertised for a kosher butcher, or shochet. The rabbi they eventually hired was recommended by the prominent Orthodox rabbi Isaac Leeser of Philadelphia. Jacob Peres (left) served B’nai Israel as its first rabbi and worked to strengthen its adherence to Orthodoxy. Under his leadership, the congregation passed a new rule stating that only members who fully observed the Sabbath could receive Torah honors on the high holidays. That such a law was needed likely indicates that most members did not strictly observe the Sabbath. Ironically, Rabbi Peres himself soon got in trouble with the congregation over Sabbath observance. Peres owned a grocery store with his brother which remained open on Saturdays. In 1860, the congregation fired Peres over the issue.

Perhaps there was more to the firing than the Sabbath issue since Children of Israel called itself a “moderate reform” congregation in its advertisement for a new rabbi. A new requirement for the job was a personal recommendation from Isaac Mayer Wise. Members who opposed this embrace of Reform broke away and formed a new congregation, Beth El Emeth, and hired as their rabbi Jacob Peres, who had remained in Memphis after his firing.

Children of Israel hired the Hungarian-born Simon Tuska as their rabbi in 1860. Under Tuska’s leadership, the congregation fully embraced Reform Judaism. In 1862, they created a mixed-gender choir; the following year, Rabbi Tuska introduced confirmation. Soon, they had an organ, mixed seating, and had adopted Wise’s Minhag America prayer book. Tuska was very popular with his congregants, and was an outspoken supporter of the Confederate cause during the Civil War. While he died young from a heart attack in 1870, Tuska managed to transform Children of Israel into a full-fledged Reform congregation during his short tenure. In 1873, Children of Israel became one of the founding members of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations.

Children of Israel hired the Hungarian-born Simon Tuska as their rabbi in 1860. Under Tuska’s leadership, the congregation fully embraced Reform Judaism. In 1862, they created a mixed-gender choir; the following year, Rabbi Tuska introduced confirmation. Soon, they had an organ, mixed seating, and had adopted Wise’s Minhag America prayer book. Tuska was very popular with his congregants, and was an outspoken supporter of the Confederate cause during the Civil War. While he died young from a heart attack in 1870, Tuska managed to transform Children of Israel into a full-fledged Reform congregation during his short tenure. In 1873, Children of Israel became one of the founding members of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations.

The congregation had 100 members in 1871 when it hired Max Samfield as its new rabbi. Born and trained in Bavaria, Samfield led B’nai Zion in Shreveport before accepting the pulpit in Memphis, a position he held for the next 44 years. Samfield was a towering figure in the Memphis Jewish community, helping to organize a local Young Men’s Hebrew Association and the Hebrew Relief Association, and serving as editor and publisher of the Jewish Spectator weekly newspaper. He also worked for the betterment of the larger community, helping to found the United Charities of Memphis. Perhaps most notably, Samfield remained in Memphis during the two major yellow fever outbreaks of the 1870s, helping to care for the afflicted and bury the dead.

The yellow fever epidemics, with their massive evacuations and high death rate, weakened the congregation, though it soon bounced back. By 1880, it had 124 member families. The outbreaks had a much more dramatic impact on Beth El Emeth, which lost its rabbi to the disease and suffered a significant drop in membership. The congregation disbanded in 1882, transferring its property and cemetery to Children of Israel. Most of Beth El Emeth’s remaining members did not rejoin the now Reform congregation, instead joining a new Orthodox congregation, Baron Hirsch.

The yellow fever epidemics, with their massive evacuations and high death rate, weakened the congregation, though it soon bounced back. By 1880, it had 124 member families. The outbreaks had a much more dramatic impact on Beth El Emeth, which lost its rabbi to the disease and suffered a significant drop in membership. The congregation disbanded in 1882, transferring its property and cemetery to Children of Israel. Most of Beth El Emeth’s remaining members did not rejoin the now Reform congregation, instead joining a new Orthodox congregation, Baron Hirsch.

While Memphis struggled to regain its economic footing after the epidemics of the 1870s, Children of Israel entered into a period of sustained growth. In 1882, the congregation purchased land for a new synagogue on Poplar Avenue, which was dedicated in January of 1884. The Byzantine-style temple had a stunning façade with two tall spires and a large round window decorated with a Star of David. The magnificent building, which cost $40,000, reflected the growing prominence of Memphis’ Jewish community. Children of Israel’s synagogue attracted new congregants. In 1885, the congregation had 173 members; by 1905, it had 262.

Despite this growth, on most Friday nights, the temple had many empty seats. Rabbi Samfield long complained that members did not attend services often enough. One member may have been trying to address the attendance problem when he proposed a new rule that the rabbi’s sermons be no longer than thirty minutes. While this solution was voted down, the attendance problem persisted. In 1907, Samfield demanded that board members be required to attend Friday night services each week. The board agreed as long as Samfield kept his sermons shorter than 25 minutes. Despite these tensions, the congregation voted to elect Samfield rabbi for life in 1910. Anticipating the eventual retirement of their longtime rabbi, the congregation hired William Fineshriber as an associate rabbi who would take eventually take over the senior position. Samfield died in September, 1915, just a few days before he was set to retire. On the day he was planning to deliver his farewell sermon, his funeral was held at the temple. Samfield was mourned throughout the city; many local businesses closed for ten minutes and every streetcar halted for one minute in his honor during his funeral.

Despite this growth, on most Friday nights, the temple had many empty seats. Rabbi Samfield long complained that members did not attend services often enough. One member may have been trying to address the attendance problem when he proposed a new rule that the rabbi’s sermons be no longer than thirty minutes. While this solution was voted down, the attendance problem persisted. In 1907, Samfield demanded that board members be required to attend Friday night services each week. The board agreed as long as Samfield kept his sermons shorter than 25 minutes. Despite these tensions, the congregation voted to elect Samfield rabbi for life in 1910. Anticipating the eventual retirement of their longtime rabbi, the congregation hired William Fineshriber as an associate rabbi who would take eventually take over the senior position. Samfield died in September, 1915, just a few days before he was set to retire. On the day he was planning to deliver his farewell sermon, his funeral was held at the temple. Samfield was mourned throughout the city; many local businesses closed for ten minutes and every streetcar halted for one minute in his honor during his funeral.

William Fineshriber took over religious leadership of Children of Israel. Fineshriber was the congregation’s first native-born rabbi and the first one to be ordained by Hebrew Union College. A very popular rabbi whose sermons covered a wide array of subjects, Fineshriber was not afraid to discuss the controversial issues of the day. When the debate over teaching evolution reached its peak in Tennessee in the 1920s, Fineshriber devoted three consecutive sermons to the subject, drawing large crowds. He also spoke out against racial violence and hatred. After a particularly brutal lynching in Memphis in 1917, Fineshriber convened a congregational meeting, and got the members to endorse a public condemnation of the attack, which ran in a local newspaper. From the pulpit, he denounced the Ku Klux Klan as a threat to American principles and more dangerous than “Bolshevism.” Fineshriber’s statements helped to encourage over civic leaders to oppose the Klan, which never took deep root in Memphis. In 1924, Rabbi Fineshriber left Children of Israel for the bigger stage of Philadelphia’s Keneseth-Israel.

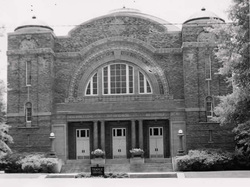

In 1912, the congregation had decided that they had outgrown their building, and began to raise money for a new synagogue. They acquired a plot of land on Poplar Avenue almost two miles east of their current home, and dedicated a new synagogue there in 1916. The new temple boasted a 1200 seat sanctuary, fourteen religious school rooms, and an auditorium with a stage. The sanctuary had an enormous $10,000 organ that was donated by the recently formed Ladies Auxiliary, whose members raised much of the money by selling home cooked meals to people downtown. Children of Israel sold their old synagogue to a new Orthodox congregation which had readopted the name Beth El Emeth.

In 1912, the congregation had decided that they had outgrown their building, and began to raise money for a new synagogue. They acquired a plot of land on Poplar Avenue almost two miles east of their current home, and dedicated a new synagogue there in 1916. The new temple boasted a 1200 seat sanctuary, fourteen religious school rooms, and an auditorium with a stage. The sanctuary had an enormous $10,000 organ that was donated by the recently formed Ladies Auxiliary, whose members raised much of the money by selling home cooked meals to people downtown. Children of Israel sold their old synagogue to a new Orthodox congregation which had readopted the name Beth El Emeth.

In 1925, Rabbi Harry Ettelson arrived to lead the congregation, which now had 650 families. Ettelson, an intellectual with a Ph.D. from Yale, was very interested in interfaith work, and organized the “Cross-Cut Club” which brought local clergy together for interfaith programs. Ettelson attracted a lot of local attention when he debated the famed lawyer and atheist Clarence Darrow on the question “is religion necessary” at the city auditorium in 1932. Ettelson was committed to the principles of classical Reform Judaism. The services he led had a lot of English and limited audience participation.

On the cusp of the Great Depression, Children of Israel had 750 member families, having almost tripled in size over the past quarter century. In order to accommodate the growing number of children, the congregation built a new religious school annex in 1926. But like many others around the country, Children of Israel was not insulated from the economic hardships of the 1930s. Their income from dues went from $47,000 in 1928 to $23,000 in 1932. Their membership dropped to a low of 629 families, as Rabbi Ettelson (left) agreed to take a pay cut to help balance the ever shrinking budget. Despite these hardships, the congregation rebounded, helped in large part by the many civic and economic leaders who belonged to Children of Israel. In 1938, Rabbi Ettelson had to take an extended medical leave, prompting the congregation to hire Morton Cohn as an assistant rabbi. Since then, the congregation, renamed Temple Israel in 1943, has always had at least two rabbis.

On the cusp of the Great Depression, Children of Israel had 750 member families, having almost tripled in size over the past quarter century. In order to accommodate the growing number of children, the congregation built a new religious school annex in 1926. But like many others around the country, Children of Israel was not insulated from the economic hardships of the 1930s. Their income from dues went from $47,000 in 1928 to $23,000 in 1932. Their membership dropped to a low of 629 families, as Rabbi Ettelson (left) agreed to take a pay cut to help balance the ever shrinking budget. Despite these hardships, the congregation rebounded, helped in large part by the many civic and economic leaders who belonged to Children of Israel. In 1938, Rabbi Ettelson had to take an extended medical leave, prompting the congregation to hire Morton Cohn as an assistant rabbi. Since then, the congregation, renamed Temple Israel in 1943, has always had at least two rabbis.

During World War II, many young members of Temple Israel fought in the armed services. The congregation’s assistant rabbi, Dudley Weinberg, served in the military chaplaincy. So many members were overseas that the congregation published a regular newsletter called “The Duffel Bag” for those in the military. The “Duffel Bag” provided news of Temple Israel as well as reports about who had been promoted, killed, or wounded. In all, fourteen members of Temple Israel died in the war.

While the controversial issue of Zionism split Reform congregations in Houston and Baton Rouge during World War II, Temple Israel was able to remain above the fray. A few leading members of the congregation, including Hardwig Peres and Louis Levy, were also leaders of the local Zionist movement. Other Children of Israel members strongly opposed the idea of a Jewish homeland, including synagogue president Milton Binswanger, who joined the anti-Zionist American Council for Judaism. Most congregants probably opposed the idea of Zionism, though Rabbi Ettelson tried to keep the congregation from getting entangled in the issue. While not a public supporter of Zionism, Ettelson chose not to join the American Council for Judaism. The congregation did not take part in Israel Bond drives in the 1950s, though many individual members did. The 1967 War helped to change the congregation’s attitude. Just after the war, the board voted to purchase Israel Bonds for the congregation’s investment fund. In 1972, Temple Israel hosted an Israel Bond dinner at the synagogue. When Israel was attacked on Yom Kippur in 1973, Temple Israel came out strongly in support of the Jewish state. As Israel reached its 25th anniversary, most of the members’ anti-Zionism had faded away.

In 1946, Temple Israel hired James Wax as an assistant rabbi, who served the congregation for over three decades. The congregation quickly fell in love with its new rabbi, and by 1947 had promoted him to associate rabbi in line to take over the senior position once Rabbi Harry Ettelson retired. This changeover took place in 1954, the same year as the monumental Brown vs. Board Education decision, which set the struggle for civil rights in motion. Rabbi Wax was committed to racial equality and social justice, arguing that “religion should transform the environment, not capitulate to it.” He spoke about civil rights from the pulpit and served on the Memphis Committee on Community Relations, which helped to peacefully integrate public facilities around town. During the racially divisive sanitation workers strike in 1968, Rabbi Wax led a delegation of ministers to meet with Mayor Henry Loeb, his former congregant, to pressure him to meet the strikers’ demands. Wax and another member of Temple Israel, Abe Plough, played a crucial role in settling the dispute.

While the controversial issue of Zionism split Reform congregations in Houston and Baton Rouge during World War II, Temple Israel was able to remain above the fray. A few leading members of the congregation, including Hardwig Peres and Louis Levy, were also leaders of the local Zionist movement. Other Children of Israel members strongly opposed the idea of a Jewish homeland, including synagogue president Milton Binswanger, who joined the anti-Zionist American Council for Judaism. Most congregants probably opposed the idea of Zionism, though Rabbi Ettelson tried to keep the congregation from getting entangled in the issue. While not a public supporter of Zionism, Ettelson chose not to join the American Council for Judaism. The congregation did not take part in Israel Bond drives in the 1950s, though many individual members did. The 1967 War helped to change the congregation’s attitude. Just after the war, the board voted to purchase Israel Bonds for the congregation’s investment fund. In 1972, Temple Israel hosted an Israel Bond dinner at the synagogue. When Israel was attacked on Yom Kippur in 1973, Temple Israel came out strongly in support of the Jewish state. As Israel reached its 25th anniversary, most of the members’ anti-Zionism had faded away.

In 1946, Temple Israel hired James Wax as an assistant rabbi, who served the congregation for over three decades. The congregation quickly fell in love with its new rabbi, and by 1947 had promoted him to associate rabbi in line to take over the senior position once Rabbi Harry Ettelson retired. This changeover took place in 1954, the same year as the monumental Brown vs. Board Education decision, which set the struggle for civil rights in motion. Rabbi Wax was committed to racial equality and social justice, arguing that “religion should transform the environment, not capitulate to it.” He spoke about civil rights from the pulpit and served on the Memphis Committee on Community Relations, which helped to peacefully integrate public facilities around town. During the racially divisive sanitation workers strike in 1968, Rabbi Wax led a delegation of ministers to meet with Mayor Henry Loeb, his former congregant, to pressure him to meet the strikers’ demands. Wax and another member of Temple Israel, Abe Plough, played a crucial role in settling the dispute.

After World War II, the congregation experienced another growth spurt. By the end of the 1940s, it had 1,100 families. Temple Israel also faced a baby boom, which soon made their educational facilities inadequate. In response, they added a new education building in 1951. They had already outgrown the new building by 1959, when they divided the school in half, with younger kids attending religious school on Saturday and older kids going on Sunday. This new system upset many parents, who created their own rump religious school in a local bank building. This religious school schism only lasted a few years.

Like other Jews in Memphis, Temple Israel members began moving away from downtown and mid-city to the eastern suburbs. As a result, Temple Israel began a long debate over whether to move east as well. By 1957, half of the congregation, including 75% of the families with children in the religious school, lived in the eastern part of the city, a long drive from the temple on Poplar Avenue. In the early 1960s, Temple Israel began to hold its weekday Hebrew classes at the conservative synagogue Beth Sholom since it was closer to where most of the students lived. In 1963, the board hired an architectural firm to design a new synagogue. Three years later, the congregation debated whether to move, and voted against building a new temple. Many of the older members worried about the expense and had a personal attachment to their current synagogue. Despite the differences among the members, there was never serious talk of breaking away to form a new congregation. Throughout this contentious debate, Temple Israel remained intact.

The problem became so acute by the early 1970s that Temple Israel’s leaders decided that a move was essential. Abe Plough, who had founded a tremendously successful pharmaceutical company, stepped in to jumpstart the effort. He offered to donate $1 million if the other top fifteen contributors would donate another $1.5 million, and the rest of the congregation raised $1.5 million. The membership accepted this offer, and voted overwhelmingly to move to a new location on East Massey Road. In the end, the new temple cost $7 million with Plough providing almost 30% of the total cost. Temple Israel moved into its large new home in September of 1976. Plough continued to offer significant financial support to his synagogue, often writing checks to cover Temple Israel’s annual budget shortfall. Even after his death, the Plough Foundation has continued as a major benefactor of the congregation, pledging $8 million during a capital campaign in 2001.

Like other Jews in Memphis, Temple Israel members began moving away from downtown and mid-city to the eastern suburbs. As a result, Temple Israel began a long debate over whether to move east as well. By 1957, half of the congregation, including 75% of the families with children in the religious school, lived in the eastern part of the city, a long drive from the temple on Poplar Avenue. In the early 1960s, Temple Israel began to hold its weekday Hebrew classes at the conservative synagogue Beth Sholom since it was closer to where most of the students lived. In 1963, the board hired an architectural firm to design a new synagogue. Three years later, the congregation debated whether to move, and voted against building a new temple. Many of the older members worried about the expense and had a personal attachment to their current synagogue. Despite the differences among the members, there was never serious talk of breaking away to form a new congregation. Throughout this contentious debate, Temple Israel remained intact.

The problem became so acute by the early 1970s that Temple Israel’s leaders decided that a move was essential. Abe Plough, who had founded a tremendously successful pharmaceutical company, stepped in to jumpstart the effort. He offered to donate $1 million if the other top fifteen contributors would donate another $1.5 million, and the rest of the congregation raised $1.5 million. The membership accepted this offer, and voted overwhelmingly to move to a new location on East Massey Road. In the end, the new temple cost $7 million with Plough providing almost 30% of the total cost. Temple Israel moved into its large new home in September of 1976. Plough continued to offer significant financial support to his synagogue, often writing checks to cover Temple Israel’s annual budget shortfall. Even after his death, the Plough Foundation has continued as a major benefactor of the congregation, pledging $8 million during a capital campaign in 2001.

Temple Israel continued its tradition of promoting its assistant rabbis to the senior position. Harry Danziger came to Temple Israel in 1964 as an assistant rabbi. Five years later, he left to lead B’nai Israel in Monroe, Louisiana. In 1973, Danziger returned to Temple Israel as an associate rabbi set to replace Rabbi Wax when he retired. Danziger called for a return to more traditional observance, saying in his first sermon in 1973 that “we can afford to look Jewish after all these years and…out of self-respect alone, we cannot afford not to.” He likened these traditions to a “trunk in the attic” that their immigrant ancestors had left; according to Danziger, it was time to reopen the trunk.

In 1978, Rabbi Wax retired and Danziger took over as senior rabbi of the 1,500-family Temple Israel. Danziger slowly but surely coaxed the congregation away from classical Reform. He did not announce any changes, choosing instead to gradually slip them into the worship services. He introduced a new modern prayer book, chanting of the Torah blessings, parading the Torahs through the aisles of the sanctuary, and even started wearing a tallis on the bimah. Cantor John Kaplan, hired in 1981, brought a more informal and interactive musical style to worship services. Micah Greenstein came to Temple Israel as an assistant rabbi in 1991, and succeeded Harry Danziger as senior rabbi in 2000.

Although some of these changes were controversial, they did not stem the tide of Temple Israel’s growth. By the end of the 1980s, Memphis’ Reform congregation had over 1700 families; more than half of the affiliated Jews in Memphis belonged to Temple Israel. In 2004, they had 1800 members and over 800 children in their religious school and youth programs. While the congregation has recently reached a plateau in its membership, it continues to offer a wide range of programs and services to a large segment of the Memphis Jewish community.

Essential Source: Judy G. Ringel, Children of Israel: The Story of Temple Israel, Memphis, Tennessee: 1854-2004.

In 1978, Rabbi Wax retired and Danziger took over as senior rabbi of the 1,500-family Temple Israel. Danziger slowly but surely coaxed the congregation away from classical Reform. He did not announce any changes, choosing instead to gradually slip them into the worship services. He introduced a new modern prayer book, chanting of the Torah blessings, parading the Torahs through the aisles of the sanctuary, and even started wearing a tallis on the bimah. Cantor John Kaplan, hired in 1981, brought a more informal and interactive musical style to worship services. Micah Greenstein came to Temple Israel as an assistant rabbi in 1991, and succeeded Harry Danziger as senior rabbi in 2000.

Although some of these changes were controversial, they did not stem the tide of Temple Israel’s growth. By the end of the 1980s, Memphis’ Reform congregation had over 1700 families; more than half of the affiliated Jews in Memphis belonged to Temple Israel. In 2004, they had 1800 members and over 800 children in their religious school and youth programs. While the congregation has recently reached a plateau in its membership, it continues to offer a wide range of programs and services to a large segment of the Memphis Jewish community.

Essential Source: Judy G. Ringel, Children of Israel: The Story of Temple Israel, Memphis, Tennessee: 1854-2004.