Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Hattiesburg, Mississippi

Overview >> Mississippi >> Hattiesburg

Historical Overview

|

The area around Hattiesburg did not attract significant European settlement until the late nineteenth century. Up to that point, the local yellow pine forests showed little agricultural promise, and the difficulties of river transport slowed the development of the lumber trade. In 1882, however, railway engineer James Hardy received a federal land grant and established Hattiesburg. (Hardy was also a Confederate veteran and participated in the movement to disenfranchise Black Mississippians in the decades following the Civil War.) Within a few years, the new town was one of many new trading centers to prosper along the new “Queen and Crescent Route,” which greatly reduced travel time between Cincinnati and New Orleans. Improved rail transit facilitated the growth of the local lumber industry as well, and Hattiesburg’s population grew to 4,000 individuals by 1900. Due to Hattiesburg’s location on several rail lines and its proximity to several important cities—namely New Orleans, Jackson, and Mobile—it earned the nickname “Hub City.”

Jewish migrants began to arrive in Hattiesburg in the early 20th century. According to one account, Maurice Dreyfus was the first Jew to settle in town, arriving in 1901 from Brookhaven, Mississippi, to operate a saw mill. Soon after, Dreyfus was joined by growing numbers of Jews drawn by the town’s economic potential. Many of the new arrivals were immigrants from the Eastern Europe. The Hattiesburg Jewish community developed over the subsequent decades and continues to operate a synagogue in the early 21st century. |

Early Jewish Residents

Many of the early Jews in Hattiesburg owned retail stores. Frank Rubenstein arrived in Hattiesburg in 1906 at the age of 22. He opened a store called “The Hub” and also owned a store in Sumrall, Mississippi, which was managed by his brother-in-law. In 1919, the Hattiesburg American newspaper called Rubenstein “one of the leading merchants of the city” and reported that he was planning on expanding his store by buying a larger building in downtown Hattiesburg for $31,000. Upon purchasing the building, he transformed the four existing businesses into one store, creating one of the largest department stores in Hattiesburg.

Jewish Life

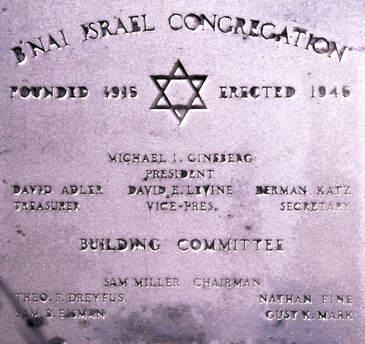

Hattiesburg Jews began to establish their own organizations within a decade of their arrival. In 1908, fifteen Jewish men founded a local chapter of B’nai B’rith (a national Jewish fraternal organization). Jewish religious services took place in private homes until the founding of Temple B’nai Israel in September of 1915. Initially, the congregation met at the local Odd Fellows hall.

The 1917 opening of Camp Shelby 15 miles south of Hattiesburg had a significant effect on the town and its young Jewish community. Soldiers from around the country passed through the military training site. The influx of personnel and the accompanying rise in business from the base helped make Hattiesburg into one of the largest cities in Mississippi. Many Jewish soldiers from the North were stationed at the camp during wartime, and members of the Hattiesburg Jewish community often hosted them for Passover seders and other events.

The 1917 opening of Camp Shelby 15 miles south of Hattiesburg had a significant effect on the town and its young Jewish community. Soldiers from around the country passed through the military training site. The influx of personnel and the accompanying rise in business from the base helped make Hattiesburg into one of the largest cities in Mississippi. Many Jewish soldiers from the North were stationed at the camp during wartime, and members of the Hattiesburg Jewish community often hosted them for Passover seders and other events.

Notice for holiday closing, Adler Dry Goods Store. (The swastikas used for the border did not yet connote Nazism.)

Notice for holiday closing, Adler Dry Goods Store. (The swastikas used for the border did not yet connote Nazism.)

In 1919 Temple B’nai Israel acquired land for a permanent home on the corner of Hardy Street and West Pine Street. The congregation was able to use building materials from the Jewish Welfare Board recreation hut at Camp Shelby, which had recently been torn down, and they finished work on the building in 1920. The synagogue was a simple, white frame structure with a sanctuary, an auditorium, and Sunday school rooms in the basement.

By 1919, many Jewish-owned stores advertised their closing for the High Holidays in the local newspaper. These stores included The Globe, The Leader Family Outfitters, L. Rubenstein & Co., Adler Dry Goods, and S & H Katz. Interestingly, all of these stores closed for two days for Rosh Hashanah, showing they were traditional in observance, but were opened again on Saturday, which reflects the compromises that even observant Jews made in order to succeed as retail merchants in small-town America.

Temple B’nai Israel has been the only synagogue in Hattiesburg throughout its history, and it has served Jews from a variety of backgrounds. When the congregation hired a Reform Rabbi, Arthur Brodey, in 1935, Orthodox members of the synagogue continued to hold periodic services separately under the lay leadership of Sam Eisman. This Orthodox faction was not marginalized within the congregation, however. In fact, Eisman served on the congregation’s board for many years.

By 1919, many Jewish-owned stores advertised their closing for the High Holidays in the local newspaper. These stores included The Globe, The Leader Family Outfitters, L. Rubenstein & Co., Adler Dry Goods, and S & H Katz. Interestingly, all of these stores closed for two days for Rosh Hashanah, showing they were traditional in observance, but were opened again on Saturday, which reflects the compromises that even observant Jews made in order to succeed as retail merchants in small-town America.

Temple B’nai Israel has been the only synagogue in Hattiesburg throughout its history, and it has served Jews from a variety of backgrounds. When the congregation hired a Reform Rabbi, Arthur Brodey, in 1935, Orthodox members of the synagogue continued to hold periodic services separately under the lay leadership of Sam Eisman. This Orthodox faction was not marginalized within the congregation, however. In fact, Eisman served on the congregation’s board for many years.

Civic Engagement and Organizational Activities

As in other small towns, Hattiesburg Jews were publicly visible as business people and merchants, and several became prominent in the general community. Russian-born Herman Katz moved to Hattiesburg in the early 1900s and served on the Board of Aldermen from 1907 to 1908. Katz was a local leader in business, civic life, and multiple fraternal organizations until his death in 1965. Herbert Ginsburg was a local attorney and a law partner of Paul Johnson Jr., who won the Mississippi gubernatorial election in 1964. Ginsburg himself served as a U.S. Magistrate during the 1960s. Jerry Shemper, whose family owned a Hattiesburg scrap business from 1905 until 2007, won election to the city council in 1997.

In addition to maintaining their own Jewish organizations, Hattiesburg Jews contributed to the development of Jewish life elsewhere in Mississippi and throughout the Deep South. Local businessman Max Signoff helped to organize the Jewish community of the Mississippi Gulf Coast in the 1950s. Lourachel “Lou” Ginsburg, the wife of Herb Ginsburg, served as the advisor for the Southern Federation of Temple Youth (SoFTY), the regional body of the Reform youth movement. She also worked at Henry S. Jacobs Camp for 24 summers.

In addition to maintaining their own Jewish organizations, Hattiesburg Jews contributed to the development of Jewish life elsewhere in Mississippi and throughout the Deep South. Local businessman Max Signoff helped to organize the Jewish community of the Mississippi Gulf Coast in the 1950s. Lourachel “Lou” Ginsburg, the wife of Herb Ginsburg, served as the advisor for the Southern Federation of Temple Youth (SoFTY), the regional body of the Reform youth movement. She also worked at Henry S. Jacobs Camp for 24 summers.

For all the public recognition that Hattiesburg Jews have received, local Jewish history is not without scandal. In December 1931 a young Black man named Andrew Prince shot a gas station owner, J. L. Odom, in the course of a robbery. Odom died the next day. When local law enforcement arrested Prince, he alleged that a young Jewish man, Paul Wexler, had served as the getaway driver. As the investigation proceeded, evidence mounted that Prince’s story was true and that he and Wexler had committed previous robberies. Wexler lived with a brother-in-law, Sam Rubenstein, who was also arrested for receiving stolen goods after the cash register from a local business was discovered at his Sumrall store. (It does not seem that Rubenstein’s case went to trial.)

Both Wexler and Prince were found guilty in January 1932 and sentenced to death. The prosecution had tried Prince first and then portrayed Wexler as the mastermind of the ill-fated robbery in the second trial. The appeals process continued until April 1933. On April 13th Paul Wexler died in prison due to complications from self-starvation, and the county executed Andrew Prince by hanging a short time later. As Leon Waldoff has written, a local Jewish leader may have suggested self-starvation to Wexler after his conviction, possibly as a means of sparing the Jewish community from the shame of having one of their own members executed by hanging. While the full truth of that story is unclear, the details of the case and its coverage in the local and statewide press certainly caused anxiety for Hattiesburg Jews. Wexler’s immediate family moved away even before his death, and the local Jewish community avoided speaking about the events in subsequent decades.

Both Wexler and Prince were found guilty in January 1932 and sentenced to death. The prosecution had tried Prince first and then portrayed Wexler as the mastermind of the ill-fated robbery in the second trial. The appeals process continued until April 1933. On April 13th Paul Wexler died in prison due to complications from self-starvation, and the county executed Andrew Prince by hanging a short time later. As Leon Waldoff has written, a local Jewish leader may have suggested self-starvation to Wexler after his conviction, possibly as a means of sparing the Jewish community from the shame of having one of their own members executed by hanging. While the full truth of that story is unclear, the details of the case and its coverage in the local and statewide press certainly caused anxiety for Hattiesburg Jews. Wexler’s immediate family moved away even before his death, and the local Jewish community avoided speaking about the events in subsequent decades.

Mid-Century Congregational Life

Temple B’nai Israel’s first clergy person, Rabbi Arthur Brodey, served the congregation until 1942. The synagogue was not able to secure a full-time replacement until they hired Rabbi David Shore in 1947. Rabbi Shore only remained for a few years, and all but one of the congregation’s subsequent rabbis worked there seven years or less. Between rabbinical hires Temple B’nai Israel often relied on student rabbis from Hebrew Union College. Both the high rate of rabbinical turnover and the reliance on student rabbis are typical for small-town synagogues.

Hattiesburg grew during the years of World War II, and Temple B’nai Israel, with 55 member families, decided to leave their building on Hardy and West Pine and build a new temple at 901 Mamie Street. (As of 2021, they still worship there.) The congregation continued to accommodate members from traditional backgrounds in their new space. On Friday nights, Orthodox men held a separate service, and the Orthodox congregants often hired an Orthodox rabbi from out-of-town to lead their High Holiday services. The congregation helped pay for the visiting Orthodox rabbi even though they had a full-time rabbi at the time. The Orthodox services were discontinued in the 1970s when there were no longer enough interested participants to form a minyan.

Hattiesburg grew during the years of World War II, and Temple B’nai Israel, with 55 member families, decided to leave their building on Hardy and West Pine and build a new temple at 901 Mamie Street. (As of 2021, they still worship there.) The congregation continued to accommodate members from traditional backgrounds in their new space. On Friday nights, Orthodox men held a separate service, and the Orthodox congregants often hired an Orthodox rabbi from out-of-town to lead their High Holiday services. The congregation helped pay for the visiting Orthodox rabbi even though they had a full-time rabbi at the time. The Orthodox services were discontinued in the 1970s when there were no longer enough interested participants to form a minyan.

Hattiesburg Jews and Black Civil Rights

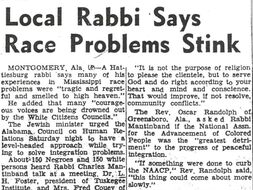

The longest tenured rabbi in the congregation’s history was Rabbi Charles Mantinband, who served from 1951 until 1963. Rabbi Mantinband was a proponent of racial equality and civil rights, arguing that Jews had a responsibility to advocate for Black civil rights because of the Jewish community’s own experiences with discrimination. Among his other activities, the rabbi was a friend and mentor of Clyde Kennard, an African American from Hattiesburg who unsuccessfully tried to desegregate Mississippi Southern University (now known as the University of Southern Mississippi) and ended up incarcerated for a fabricated (and retaliatory) theft conviction. Despite Rabbi Mantinband’s public stances on the desirability and inevitability of desegregation, he tried to work subtly and in the background whenever possible.

Fearful of economic consequences and violent reprisals, congregants tried to get Mantinband to quiet his voice on civil rights issues. The local White Citizens’ Council suggested that Temple B’nai Israel could become a target if members failed to dismiss their outspoken rabbi. Merchant congregants who had heavy investments in Hattiesburg businesses were especially concerned that their livelihoods might suffer from boycotts directed at the Jewish community. Throughout his tenure, Mantinband faced pressure from a congregation that wanted him to stay out of the brewing struggle. Finally, in 1963, Mantinband left Hattiesburg for Temple Emanu-El in Longview, Texas.

Fearful of economic consequences and violent reprisals, congregants tried to get Mantinband to quiet his voice on civil rights issues. The local White Citizens’ Council suggested that Temple B’nai Israel could become a target if members failed to dismiss their outspoken rabbi. Merchant congregants who had heavy investments in Hattiesburg businesses were especially concerned that their livelihoods might suffer from boycotts directed at the Jewish community. Throughout his tenure, Mantinband faced pressure from a congregation that wanted him to stay out of the brewing struggle. Finally, in 1963, Mantinband left Hattiesburg for Temple Emanu-El in Longview, Texas.

A headline in the Hattiesburg American, Feb. 13, 1956.

A headline in the Hattiesburg American, Feb. 13, 1956.

A significant proportion of Hattiesburg Jews would have preferred for Rabbi Mantinband to remain out of the public eye, either because they supported segregation or because they feared retribution from white supremacist groups. He was not the only local Jew to object to the poor treatment of African Americans, however. Local broadcaster Marvin Reuben served as the general manager of local NBC-affiliate WDAM-TV and was also a part owner of the station. Reuben delivered on-air editorials in support of desegregation and in opposition to violent white supremacists. In response, the Ku Klux Klan made efforts to silence him; they threw acid on his wife’s car, shot the radio tower, and burned three crosses in front of the television station. While Reuben’s views earned him harassment at the time, he was eventually honored for his stance. In 1992, he received the Hub Award—an annual recognition for contributing to the betterment of the city—and the mayor proclaimed “Marvin Reuben Day.”

Of course, the struggle over Black civil rights did not end with Rabbi Mantinband’s departure in 1963. His successor, Rabbi David Ben-Ami, also supported the cause of Black equality, which led to his departure from the synagogue by early 1965. Following the arrest of several out-of-state clergy activists in January 1964, Rabbi Ben-Ami was the only Hattiesburg clergyman to visit the arrestees. The sheriff reported the rabbi’s actions to the congregation in an attempt to silence the rabbi or have him fired.

Shortly thereafter, Rabbi Ben-Ami became friends with Reverend Robert Beech of the Federal Council of Churches, who had moved to Hattiesburg with the intention of building cross-racial alliances. Reverend Beech was refused entry into the local (white) Presbyterian Church, and Rabbi Ben-Ami was the only white clergy member who would have anything to do with him. According to historian Clive Webb, the collaboration between Rabbi Ben-Ami and Reverend Beech prompted another meeting between the rabbi and the board, and Rabbi Ben-Ami resigned. By February 1965, Ben-Ami and his family had relocated to Washington, D. C..

Of course, the struggle over Black civil rights did not end with Rabbi Mantinband’s departure in 1963. His successor, Rabbi David Ben-Ami, also supported the cause of Black equality, which led to his departure from the synagogue by early 1965. Following the arrest of several out-of-state clergy activists in January 1964, Rabbi Ben-Ami was the only Hattiesburg clergyman to visit the arrestees. The sheriff reported the rabbi’s actions to the congregation in an attempt to silence the rabbi or have him fired.

Shortly thereafter, Rabbi Ben-Ami became friends with Reverend Robert Beech of the Federal Council of Churches, who had moved to Hattiesburg with the intention of building cross-racial alliances. Reverend Beech was refused entry into the local (white) Presbyterian Church, and Rabbi Ben-Ami was the only white clergy member who would have anything to do with him. According to historian Clive Webb, the collaboration between Rabbi Ben-Ami and Reverend Beech prompted another meeting between the rabbi and the board, and Rabbi Ben-Ami resigned. By February 1965, Ben-Ami and his family had relocated to Washington, D. C..

A Succession of Rabbis

Student Rabbi Sally Priesand with Michael Ginsberg at his bar mitzvah ceremony, c. 1969.

Student Rabbi Sally Priesand with Michael Ginsberg at his bar mitzvah ceremony, c. 1969.

Hattiesburg Jews often relied on student rabbis to provide religious services when the congregation was between hires. In 1969, Temple B’nai Israel members faced the decision of whether to accept a woman as their student rabbi when Hebrew Union College assigned Sally Priesand to the position. At the time, she was the Reform movement’s first female rabbinical student, and she became the first woman ordained as rabbi in the United States in 1972. A traditionalist faction within the congregation strongly opposed allowing a woman to serve as clergy, and the voting process became so confusing that the final tally was conducted by having congregants stand on opposite sides of a room. Eventually, Temple B’nai Israel accepted Priesand. They provided a welcoming student pulpit, and most of the year-long appointment went smoothly and without controversy. Twenty years later, the congregation became the first Mississippi synagogue to hire a female full-time rabbi when Judith Bluestein led the congregation.

Among Temple B’nai Israel’s student rabbis was Norman Lipson, who served there during the 1971-1972 school year. The congregation liked him so much that they raised enough money to hire him as a full-time Rabbi from 1974-1977. Following his tenure, the congregation alternated between a series of full-time and student rabbis. Full-time rabbis during this period included: Samuel Rothberg (1977-1980); David Ostrich (1982-1984); Cyril Stanway (1987-1990); Judith Bluestein (1990-1994); Reena Judd (1994-1997); Celso Cukierkorn (2000-2007); and Uri Barnea, (2007-2014). At the time of Rabbi Barnea’s retirement, the congregation no longer had a large enough membership to support the salary of a full-time rabbi. As of 2020, Temple B’nai Israel employed Rabbi Edward Cohn—rabbi emeritus at Temple Sinai in New Orleans—for regular services.

Among Temple B’nai Israel’s student rabbis was Norman Lipson, who served there during the 1971-1972 school year. The congregation liked him so much that they raised enough money to hire him as a full-time Rabbi from 1974-1977. Following his tenure, the congregation alternated between a series of full-time and student rabbis. Full-time rabbis during this period included: Samuel Rothberg (1977-1980); David Ostrich (1982-1984); Cyril Stanway (1987-1990); Judith Bluestein (1990-1994); Reena Judd (1994-1997); Celso Cukierkorn (2000-2007); and Uri Barnea, (2007-2014). At the time of Rabbi Barnea’s retirement, the congregation no longer had a large enough membership to support the salary of a full-time rabbi. As of 2020, Temple B’nai Israel employed Rabbi Edward Cohn—rabbi emeritus at Temple Sinai in New Orleans—for regular services.

The Late 20th and Early 21st Centuries

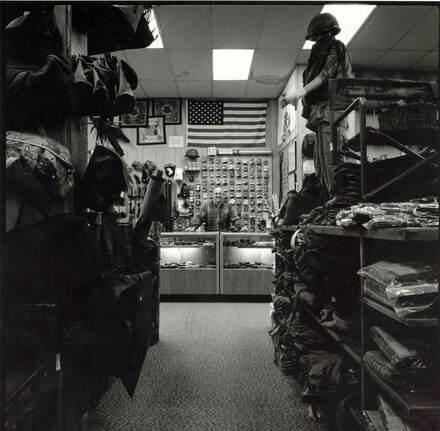

Jewish occupational trends in Hattiesburg mirrored those in other small cities. While the earliest founders of Temple B’nai Israel were mostly merchant families, a large portion of 21st-century congregants are medical practitioners or employees of the University of Southern Mississippi. Jewish participation in local retail began declining by the 1970s, and the opening of a local mall in 1975 pulled customers away from the downtown shopping district where a number of Jewish merchants once made their livings. As of 2021, Sack’s Outdoor Store is the only remaining Jewish retail business in Hattiesburg. Camp Shelby remains a significant piece of the local economy, and the congregation occasionally hosts Jewish soldiers who pass through the nearby training facility.

The general population of Hattiesburg has remained relatively steady since 1970, and the area still serves as a medical, educational, and business hub for the Mississippi Pine Belt. So, while the Jewish population is smaller than it once was, it has not declined as rapidly as in some other small Jewish communities. An estimated 215 Jews lived there in 1937, and that number was 180 in 1984. By 2001, the figure stood at 130. While the congregation is not growing, it remains relatively stable and continues to hold regular services and operate a small religious school as of 2021.

The general population of Hattiesburg has remained relatively steady since 1970, and the area still serves as a medical, educational, and business hub for the Mississippi Pine Belt. So, while the Jewish population is smaller than it once was, it has not declined as rapidly as in some other small Jewish communities. An estimated 215 Jews lived there in 1937, and that number was 180 in 1984. By 2001, the figure stood at 130. While the congregation is not growing, it remains relatively stable and continues to hold regular services and operate a small religious school as of 2021.

Selected Bibliography

Lourachael Ginsberg, oral history interview by Johan Kern, March 15, 2013, The Center for Oral History and Cultural Heritage, The University of Southern Mississippi.

William Sturkey, Hattiesburg: An American City in Black and White (Harvard University Press, 2019).

Leon Waldoff, A Story of Jewish Experience in Mississippi (Academic Studies Press, 2018).

Clive Webb, “Big Struggle in a Small Town: Charles Mantinband of Hattiesburg, Mississippi,” The Quiet Voices: Southern Rabbis and Black Civil Rights, 1880s to 1990s, eds. Mark Bauman and Berkley Kalin (University of Alabama Press, 1997).

Clive Webb, Fight Against Fear: Southern Jews and Black Civil Rights (University of Georgia Press, 2003).

Lourachael Ginsberg, oral history interview by Johan Kern, March 15, 2013, The Center for Oral History and Cultural Heritage, The University of Southern Mississippi.

William Sturkey, Hattiesburg: An American City in Black and White (Harvard University Press, 2019).

Leon Waldoff, A Story of Jewish Experience in Mississippi (Academic Studies Press, 2018).

Clive Webb, “Big Struggle in a Small Town: Charles Mantinband of Hattiesburg, Mississippi,” The Quiet Voices: Southern Rabbis and Black Civil Rights, 1880s to 1990s, eds. Mark Bauman and Berkley Kalin (University of Alabama Press, 1997).

Clive Webb, Fight Against Fear: Southern Jews and Black Civil Rights (University of Georgia Press, 2003).