Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Kilgore/Longview, Texas

Kilgore/Longview: Historical Overview

|

In the early 1930s, as the unemployment and despair of the Great Depression ravaged the lives of countless Americans, for those daring enough to try their luck, a small pocket of wealth and prosperity sprouted in the oil fields of East Texas. The East Texas oil boom attracted Americans from many walks of life, Jews among them, all seeking an opportunity in a disheartened country. As if overnight, the population of the small town of Kilgore, Texas, soared after the discovery of oil. Similarly, Longview, just a few minutes’ drive from Kilgore, grew and, as the closest urban center to the oil towns, continued to do so for many years.

While a small population of Jews lived in Longview’s surrounding area prior to the discovery of oil, the organization of the Jews of Kilgore and Longview, with support from Jews of outlying towns such as Henderson, began shortly after the influx of Jews during the oil boom. Jews have thrived in Kilgore and Longview since their arrival and while many of those who arrived alongside them have long since moved away, a Jewish community still stands in Longview today. |

Stories of the Jewish Community in Kilgore and Longview

.A. Bodenheim spent 14 years

.A. Bodenheim spent 14 years as Longview's mayor

Early Settlers

Despite the nearby presence of various railroads, Longview, the county seat of Gregg County, was a town of just 1,525 in 1882. Among Longview’s small population were a few Jews: from 1876 to 1878, at least five men from Longview and some from Kilgore joined the B’nai B’rith Lodge in nearby Marshall, Texas, about 25 miles from Longview. By 1920, Longview’s population had grown to 5,713 and many Jews had found success as businesspeople. For example, S.H. Bissinger and Joseph Newman were grocers, Louie Richkie was a tailor, and Isaac Gans, Morris Goldberg, Max Rosenfield, and Frank Goldstein were all dry good merchants. Gans’ son Daniel, listed in the 1900 census as a “salesman,” became a partner in an insurance firm, Brown, Gans & Co., renamed Gans & Smith in 1912, a name it still bears though no Gans family member maintains any association with the company. Dan Gans was a well respected and popular Longview citizen, so much so that his funeral, officiated by a rabbi, was so large that it needed to be held in the crowded auditorium of the First Baptist Church. One possibly apocryphal story illustrates Dan’s status in the Longview community: when the Ku Klux Klan attempted to start a chapter in Longview, an initial organizational meeting was held. When Dan’s friends realized that Dan would not be invited to join the Klan because he was Jewish, they refused to join and no Klan chapter was formed in Longview at that time

Another key Jewish figure in the early years of Longview was G.A. “Bodie” Bodenheim. Born in Vicksburg, Mississippi in 1873, Gabriel Augustus Bodenheim arrived in Longview in 1898 to buy cotton. In 1901 he married Methodist Willie Bass and in 1904 was elected Longview’s mayor, a position he would hold until 1916 and again from 1918 to 1920. As mayor, Bodenheim, with his trademark red carnation and golden cane, proved instrumental to Longview’s growth and development. “Colonel Bodie” supervised the annexation of nearby Longview Junction, raising Longview’s population above 5,000 and thus allowing the city, under state law, to sell city-improvement bonds. Additionally, under Bodenheim’s leadership, Longview saw its first paved streets, health department, paid fire department, and modern sewage and street light systems. Throughout his years as a public servant, Bodenheim remained a successful cotton merchant and also founded an insurance firm in 1907.

After World War I, Bodenheim focused solely on the Bodenheim Insurance Agency which became one of Texas’ leading insurance firms. Bodie Park, a park in Longview later sold during the oil boom and Bodie, Texas a farming community and former railroad stop near Longview, were named in honor of Bodenheim.Though Bodenheim joined his wife’s church and a Methodist minister shared the pulpit with a rabbi at his funeral, he remained involved in the Jewish community, especially in B’nai B’rith.

Longview was not the only East Texas destination for Jews in the pre-oil-boom era. In 1874 merchant Benjamin Brachfield and his six children arrived in Henderson, a town 25 miles south of Longview. One of Brachfield’s sons, Charles, grand-uncle of longtime Texas Congressman Martin Frost, served as a Rusk County Judge and state senator, was elected judge of a five-county constituency, and ran an unsuccessful campaign for attorney general in 1926, the first statewide office in Texas pursued by a Jewish candidate. Nathan Marwilsky, a native of Poland, arrived in Henderson in the 1880s and opened a saloon but soon thereafter became a grocer and later opened a dry goods store. One of Marwilsky’s sons, Moses, shortened his last name to Marwil and served two terms as mayor of Henderson starting in 1936.

Despite the nearby presence of various railroads, Longview, the county seat of Gregg County, was a town of just 1,525 in 1882. Among Longview’s small population were a few Jews: from 1876 to 1878, at least five men from Longview and some from Kilgore joined the B’nai B’rith Lodge in nearby Marshall, Texas, about 25 miles from Longview. By 1920, Longview’s population had grown to 5,713 and many Jews had found success as businesspeople. For example, S.H. Bissinger and Joseph Newman were grocers, Louie Richkie was a tailor, and Isaac Gans, Morris Goldberg, Max Rosenfield, and Frank Goldstein were all dry good merchants. Gans’ son Daniel, listed in the 1900 census as a “salesman,” became a partner in an insurance firm, Brown, Gans & Co., renamed Gans & Smith in 1912, a name it still bears though no Gans family member maintains any association with the company. Dan Gans was a well respected and popular Longview citizen, so much so that his funeral, officiated by a rabbi, was so large that it needed to be held in the crowded auditorium of the First Baptist Church. One possibly apocryphal story illustrates Dan’s status in the Longview community: when the Ku Klux Klan attempted to start a chapter in Longview, an initial organizational meeting was held. When Dan’s friends realized that Dan would not be invited to join the Klan because he was Jewish, they refused to join and no Klan chapter was formed in Longview at that time

Another key Jewish figure in the early years of Longview was G.A. “Bodie” Bodenheim. Born in Vicksburg, Mississippi in 1873, Gabriel Augustus Bodenheim arrived in Longview in 1898 to buy cotton. In 1901 he married Methodist Willie Bass and in 1904 was elected Longview’s mayor, a position he would hold until 1916 and again from 1918 to 1920. As mayor, Bodenheim, with his trademark red carnation and golden cane, proved instrumental to Longview’s growth and development. “Colonel Bodie” supervised the annexation of nearby Longview Junction, raising Longview’s population above 5,000 and thus allowing the city, under state law, to sell city-improvement bonds. Additionally, under Bodenheim’s leadership, Longview saw its first paved streets, health department, paid fire department, and modern sewage and street light systems. Throughout his years as a public servant, Bodenheim remained a successful cotton merchant and also founded an insurance firm in 1907.

After World War I, Bodenheim focused solely on the Bodenheim Insurance Agency which became one of Texas’ leading insurance firms. Bodie Park, a park in Longview later sold during the oil boom and Bodie, Texas a farming community and former railroad stop near Longview, were named in honor of Bodenheim.Though Bodenheim joined his wife’s church and a Methodist minister shared the pulpit with a rabbi at his funeral, he remained involved in the Jewish community, especially in B’nai B’rith.

Longview was not the only East Texas destination for Jews in the pre-oil-boom era. In 1874 merchant Benjamin Brachfield and his six children arrived in Henderson, a town 25 miles south of Longview. One of Brachfield’s sons, Charles, grand-uncle of longtime Texas Congressman Martin Frost, served as a Rusk County Judge and state senator, was elected judge of a five-county constituency, and ran an unsuccessful campaign for attorney general in 1926, the first statewide office in Texas pursued by a Jewish candidate. Nathan Marwilsky, a native of Poland, arrived in Henderson in the 1880s and opened a saloon but soon thereafter became a grocer and later opened a dry goods store. One of Marwilsky’s sons, Moses, shortened his last name to Marwil and served two terms as mayor of Henderson starting in 1936.

Oil derricks sprung up throughout

Oil derricks sprung up throughout Kilgore's downtown in the 1930s

The Oil Boom

The discovery of oil in East Texas in the fall of 1930 forever changed the landscape of Kilgore and Longview. Kilgore, whose population in 1930 was 500 people, became a raucous city of 10,000 two months after the discovery of oil. Henderson’s population increased from 3,000 in 1930 to 10,000 in 1933 and Longview, where the population had recently fallen to 5,036 in 1930, had 13,758 residents by 1940 despite the drop in the oil economy in the late 1930s. Among those who arrived in the remote plains of East Texas were Jews from former boomtowns in Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Texas, as well as elsewhere in the United States.

Upon arriving in East Texas, many Jews found a place in the booming oil business. Sonnel Felsenthal ran an oil production and shipping business. Sam Dorfman, owner of Louisiana Pipe and Supply, a scrap metal business, co-founded Delta Drilling Company and was perhaps the most successful Jewish businessman in the area. Irving Falk and Sam Weldman started a very successful scrap metal business and worked intimately with the oil companies of East Texas. Longview’s 1960 city directory lists Falk as president of both Industrial Steel Warehouse Inc. and Texas Scrap and Material Co. Falk’s brother-in-law, Morris Milstein, the secretary and treasurer of both companies by 1960, ran the businesses while Falk served in the army in World War II and eventually bought out Sam Weldman’s share. Morris’ son, Howard “Rusty” Milstein, ran Texas Scrap and Material, renamed Industrial Steel Warehouse Inc., until the 1990s. Other Jews involved in the scrap metal business include the Sanov family, Bernard Rose, and Isador Levinson, an iron and metal merchant. Harry Sobol came to Kilgore and opened Sobol Welders Supply immediately after oil was struck. Sobol eventually sold the business to his son-in-law, Smiley Rabicoff, who, because the oil derricks ran 24 hours a day, also kept his store open day and night during the oil boom and World War II. In 1975, Smiley's son Mendy Rabicoff took over the family business which he continued to operate in 2011.

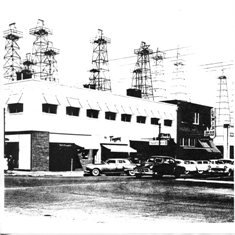

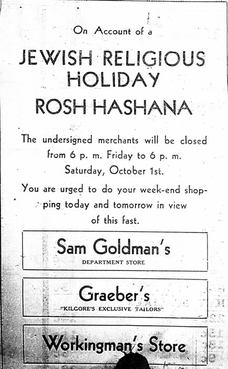

Jewish merchants were drawn to the area to cater to Kilgore and Longview’s growing population of oil workers. Joe Waldman arrived in Kilgore in 1931, opening the Fair Store. Hyman Hurwitz opened the Hub at the start of the boom and his store, later renamed Hurwitz Man’s Shop, became one of the area’s most successful clothing stores. Daiches Jewelry, too, opened in 1932 and became one of the city’s most fashionable businesses. Other Jewish-owned stores in Kilgore in the 1930s include K. Wolens Department Store, Kaplan’s Department Store, The Toggery (shoes and women’s clothes), Sam Goldman’s Department Store, Graeber’s Tailors, the Workingman’s Store, and The Model Men’s Store. Jewish merchants opened stores in Longview in the early 1930s as well, including Davis and Maritsky’s clothing store, Gans Men’s Wear, Silver’s Shoe Store, and Riff’s women’s clothing store. Jewish businesses were so prominent that on the High Holidays, when most Jewish stores were closed, downtown Kilgore and Longview were practically closed as well. Not all Jews were merchants; a handful were professionals. Haskell Heiligman, Ben Andres, and Dr. Balinsky were doctors, while Bill Hurwitz and Phillip Brin were attorneys.

The discovery of oil in East Texas in the fall of 1930 forever changed the landscape of Kilgore and Longview. Kilgore, whose population in 1930 was 500 people, became a raucous city of 10,000 two months after the discovery of oil. Henderson’s population increased from 3,000 in 1930 to 10,000 in 1933 and Longview, where the population had recently fallen to 5,036 in 1930, had 13,758 residents by 1940 despite the drop in the oil economy in the late 1930s. Among those who arrived in the remote plains of East Texas were Jews from former boomtowns in Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Texas, as well as elsewhere in the United States.

Upon arriving in East Texas, many Jews found a place in the booming oil business. Sonnel Felsenthal ran an oil production and shipping business. Sam Dorfman, owner of Louisiana Pipe and Supply, a scrap metal business, co-founded Delta Drilling Company and was perhaps the most successful Jewish businessman in the area. Irving Falk and Sam Weldman started a very successful scrap metal business and worked intimately with the oil companies of East Texas. Longview’s 1960 city directory lists Falk as president of both Industrial Steel Warehouse Inc. and Texas Scrap and Material Co. Falk’s brother-in-law, Morris Milstein, the secretary and treasurer of both companies by 1960, ran the businesses while Falk served in the army in World War II and eventually bought out Sam Weldman’s share. Morris’ son, Howard “Rusty” Milstein, ran Texas Scrap and Material, renamed Industrial Steel Warehouse Inc., until the 1990s. Other Jews involved in the scrap metal business include the Sanov family, Bernard Rose, and Isador Levinson, an iron and metal merchant. Harry Sobol came to Kilgore and opened Sobol Welders Supply immediately after oil was struck. Sobol eventually sold the business to his son-in-law, Smiley Rabicoff, who, because the oil derricks ran 24 hours a day, also kept his store open day and night during the oil boom and World War II. In 1975, Smiley's son Mendy Rabicoff took over the family business which he continued to operate in 2011.

Jewish merchants were drawn to the area to cater to Kilgore and Longview’s growing population of oil workers. Joe Waldman arrived in Kilgore in 1931, opening the Fair Store. Hyman Hurwitz opened the Hub at the start of the boom and his store, later renamed Hurwitz Man’s Shop, became one of the area’s most successful clothing stores. Daiches Jewelry, too, opened in 1932 and became one of the city’s most fashionable businesses. Other Jewish-owned stores in Kilgore in the 1930s include K. Wolens Department Store, Kaplan’s Department Store, The Toggery (shoes and women’s clothes), Sam Goldman’s Department Store, Graeber’s Tailors, the Workingman’s Store, and The Model Men’s Store. Jewish merchants opened stores in Longview in the early 1930s as well, including Davis and Maritsky’s clothing store, Gans Men’s Wear, Silver’s Shoe Store, and Riff’s women’s clothing store. Jewish businesses were so prominent that on the High Holidays, when most Jewish stores were closed, downtown Kilgore and Longview were practically closed as well. Not all Jews were merchants; a handful were professionals. Haskell Heiligman, Ben Andres, and Dr. Balinsky were doctors, while Bill Hurwitz and Phillip Brin were attorneys.

Joe Waldman, owner of Kilgore's Fair Store

Joe Waldman, owner of Kilgore's Fair Store

Organized Jewish Life in Kilgore and Longview

With this tremendous growth in the early 1930s, local Jews soon began to organize. While many Reform Jews would travel to nearby Marshall to attend High Holiday services at Temple Moses Montefiore, enough Jews lived in Longview and Kilgore in the 1930s that Orthodox and Conservative Jews were able to organize their own services. In October, 1932, local Jews met for High Holiday services at the Labor Temple in Kilgore. In 1935, they brought in an Orthodox student rabbi from the Hebrew Theological College in Chicago to lead the traditional two days of Rosh Hashanah services at Kilgore City Hall. In other years, High Holiday services would be held above McCarley’s Jewelry Store in Longview or above the fire station in Kilgore which, because of the frequency of fires in the oil towns, was often an adventure. Sunday school was also held in local stores, though the doors had to be kept shut to abide by Texas’ blue laws, causing almost unbearable heat in the summer. Minyanim (prayer services involving at least ten men) for individuals’ yahrzeits (the anniversary of the death of a close relative) were also hosted in various stores. With 22 to 25 Jewish families living in Kilgore alone in 1935, the joint Jewish communities of Kilgore and Longview were large and active enough in the mid-1930s that they began to discuss building a synagogue.

Anne Rose, who was instrumental in the formation of a Jewish Women’s Auxiliary and the Sunday school, led the fundraising effort to buy land and build a synagogue. Arguments arose at an initial meeting in the 1930s as to whether the planned synagogue would be Orthodox or Reform and whether or not Jewish dietary laws would be observed within the building, but these differences were overcome and Beth Sholom, aptly meaning “House of Peace,” was completed in 1936. Rosh Hashanah services officiated in 1936 by Rabbi Benjamin Eisenberg of the Hebrew Theological College marked the formal opening of the synagogue. The congregation was traditional, celebrating two days for the Jewish new year.

Though the Kilgore Herald referred to Beth Sholom as the home of the “Kilgore Jewish congregation,” Beth Sholom was always meant to serve the Jews of Kilgore, Longview, and other neighboring towns as well. While more Jews lived in Longview than in Kilgore, all of the members of a key synagogue planning committee were residents of Kilgore, and many of Longview’s Jews attended the Reform temple in Marshall. Therefore, most of Congregation Beth Sholom’s membership came from Kilgore with some members from the other surrounding towns of Gladewater and Overton. Three families from Henderson joined Beth Sholom in 1950 and became active in the synagogue; Jews from surrounding towns such as Gilmer, would drive into Kilgore for High Holiday services.

With this tremendous growth in the early 1930s, local Jews soon began to organize. While many Reform Jews would travel to nearby Marshall to attend High Holiday services at Temple Moses Montefiore, enough Jews lived in Longview and Kilgore in the 1930s that Orthodox and Conservative Jews were able to organize their own services. In October, 1932, local Jews met for High Holiday services at the Labor Temple in Kilgore. In 1935, they brought in an Orthodox student rabbi from the Hebrew Theological College in Chicago to lead the traditional two days of Rosh Hashanah services at Kilgore City Hall. In other years, High Holiday services would be held above McCarley’s Jewelry Store in Longview or above the fire station in Kilgore which, because of the frequency of fires in the oil towns, was often an adventure. Sunday school was also held in local stores, though the doors had to be kept shut to abide by Texas’ blue laws, causing almost unbearable heat in the summer. Minyanim (prayer services involving at least ten men) for individuals’ yahrzeits (the anniversary of the death of a close relative) were also hosted in various stores. With 22 to 25 Jewish families living in Kilgore alone in 1935, the joint Jewish communities of Kilgore and Longview were large and active enough in the mid-1930s that they began to discuss building a synagogue.

Anne Rose, who was instrumental in the formation of a Jewish Women’s Auxiliary and the Sunday school, led the fundraising effort to buy land and build a synagogue. Arguments arose at an initial meeting in the 1930s as to whether the planned synagogue would be Orthodox or Reform and whether or not Jewish dietary laws would be observed within the building, but these differences were overcome and Beth Sholom, aptly meaning “House of Peace,” was completed in 1936. Rosh Hashanah services officiated in 1936 by Rabbi Benjamin Eisenberg of the Hebrew Theological College marked the formal opening of the synagogue. The congregation was traditional, celebrating two days for the Jewish new year.

Though the Kilgore Herald referred to Beth Sholom as the home of the “Kilgore Jewish congregation,” Beth Sholom was always meant to serve the Jews of Kilgore, Longview, and other neighboring towns as well. While more Jews lived in Longview than in Kilgore, all of the members of a key synagogue planning committee were residents of Kilgore, and many of Longview’s Jews attended the Reform temple in Marshall. Therefore, most of Congregation Beth Sholom’s membership came from Kilgore with some members from the other surrounding towns of Gladewater and Overton. Three families from Henderson joined Beth Sholom in 1950 and became active in the synagogue; Jews from surrounding towns such as Gilmer, would drive into Kilgore for High Holiday services.

The 1930s and 1940s

The Jews of Kilgore and Longview extended their hospitality to the Jewish servicemen stationed in the area during World War II. Jewish residents of Longview would visit the wounded soldiers in Harmon General Hospital just outside of Longview. Members of the Longview-Kilgore community, too, invited the soldiers into their homes for dinner, or, in Abe Sosland’s case, organized Shabbat dinners at the hospital. The Jewish community also held Passover seders for the soldiers, many of whom were from the Northeast and in an unfamiliar place where they had not expected to find other Jews.

The Jewish communities in Kilgore and Longview remained strong in the 1930s and 1940s, even as the area’s oil production vacillated. Beth Sholom’s first rabbi, hired in 1938, was Joseph Gerstein. The Orthodox rabbi brought a flurry of activity to the building, helping to organize adult Hebrew classes, weekly Shabbat services, a three-day-a-week Hebrew School, and a bi-weekly women’s study group in Jewish history. Kilgore also had B’nai B’rith and Hadassah chapters at the time. Rabbi Gerstein did not stay for long, and was replaced in 1940 by Conservative Rabbi Peter Novetsky. Congregation Beth Sholom continued to move away from Orthodoxy after World War II, eventually adopting Reform Judaism, which caused some traditional members to resign from the synagogue. Beth Sholom hired it first reform rabbi, Simon Cohen, in 1954. Rabbi Cohen did not last long, and was replaced later that year by Daniel Kerman, who served the congregation until 1957. Though their synagogue had been constructed less than decade earlier, Beth Sholom had grown so much that it needed a larger facility. Around 1945, Hyman Hurwitz purchased a former bar and gambling house that was slated for demolition and had it moved next to the synagogue. Beth Sholom refurbished this former “honky tonk”, creating a new social hall and classrooms for the overcrowded Sunday school.

The Jews of Kilgore and Longview extended their hospitality to the Jewish servicemen stationed in the area during World War II. Jewish residents of Longview would visit the wounded soldiers in Harmon General Hospital just outside of Longview. Members of the Longview-Kilgore community, too, invited the soldiers into their homes for dinner, or, in Abe Sosland’s case, organized Shabbat dinners at the hospital. The Jewish community also held Passover seders for the soldiers, many of whom were from the Northeast and in an unfamiliar place where they had not expected to find other Jews.

The Jewish communities in Kilgore and Longview remained strong in the 1930s and 1940s, even as the area’s oil production vacillated. Beth Sholom’s first rabbi, hired in 1938, was Joseph Gerstein. The Orthodox rabbi brought a flurry of activity to the building, helping to organize adult Hebrew classes, weekly Shabbat services, a three-day-a-week Hebrew School, and a bi-weekly women’s study group in Jewish history. Kilgore also had B’nai B’rith and Hadassah chapters at the time. Rabbi Gerstein did not stay for long, and was replaced in 1940 by Conservative Rabbi Peter Novetsky. Congregation Beth Sholom continued to move away from Orthodoxy after World War II, eventually adopting Reform Judaism, which caused some traditional members to resign from the synagogue. Beth Sholom hired it first reform rabbi, Simon Cohen, in 1954. Rabbi Cohen did not last long, and was replaced later that year by Daniel Kerman, who served the congregation until 1957. Though their synagogue had been constructed less than decade earlier, Beth Sholom had grown so much that it needed a larger facility. Around 1945, Hyman Hurwitz purchased a former bar and gambling house that was slated for demolition and had it moved next to the synagogue. Beth Sholom refurbished this former “honky tonk”, creating a new social hall and classrooms for the overcrowded Sunday school.

Beth Sholom Synagogue in Kilgore. Photo courtesy of Mike Joseph

Beth Sholom Synagogue in Kilgore. Photo courtesy of Mike Joseph

The Mid-Century

By 1957, with a membership of 96 families, 51 of whom came from Longview, 28 from Kilgore, and 17 from the surrounding area, Congregation Beth Sholom decided to build a new synagogue. An expansion committee decided that since more Jews lived in Longview than Kilgore and Longview’s Jews were hesitant to pay for another building not located in their town, the new synagogue would be located in Longview. The members from Kilgore were, naturally, upset with this decision, as they were satisfied with the building’s current facilities and were hesitant to pay for a new one. Nonetheless, construction of a new synagogue in Longview began following the purchase of a plot of land in 1957. Even after the new temple’s completion, however, around 20 members of Kilgore’s Beth Sholom refused to make the move to Longview and continued meeting in the original building. The charter membership of the new Beth Sholom in Longview for the year of 1959-1960 included 54 individuals or families from Longview, 12 from Kilgore, and four from Gladewater.

Construction of the new synagogue in Longview was completed in April, 1958 with a sanctuary named for Sam Dorfman and a social hall named for Sonnel Felsenthal. Rabbi Malcolm Cohen was hired in August of that year and, to avoid confusion with the temple in Kilgore, Beth Shalom in Longview was renamed Temple Emanu-El in October. The synagogue had been in use for a few months prior to its dedication, hence the Longview Daily News’ September 15th, 1958 announcement that Rosh Hashanah services would be held at the synagogue, but a three day dedication service, featuring visiting rabbis from Beaumont and Tyler, Texas and Shreveport, Louisiana, was not held until November of 1958. The Longview Sunday News Journal editorialized on the final day of the dedication ceremonies that the construction of the synagogue “signifies growth and development of the [Longview] community to a stage of more substantial and mature permanence.” The editorial noted that the ceremony was open to the public and that civic and Christian leaders from Longview would be in attendance.

By 1957, with a membership of 96 families, 51 of whom came from Longview, 28 from Kilgore, and 17 from the surrounding area, Congregation Beth Sholom decided to build a new synagogue. An expansion committee decided that since more Jews lived in Longview than Kilgore and Longview’s Jews were hesitant to pay for another building not located in their town, the new synagogue would be located in Longview. The members from Kilgore were, naturally, upset with this decision, as they were satisfied with the building’s current facilities and were hesitant to pay for a new one. Nonetheless, construction of a new synagogue in Longview began following the purchase of a plot of land in 1957. Even after the new temple’s completion, however, around 20 members of Kilgore’s Beth Sholom refused to make the move to Longview and continued meeting in the original building. The charter membership of the new Beth Sholom in Longview for the year of 1959-1960 included 54 individuals or families from Longview, 12 from Kilgore, and four from Gladewater.

Construction of the new synagogue in Longview was completed in April, 1958 with a sanctuary named for Sam Dorfman and a social hall named for Sonnel Felsenthal. Rabbi Malcolm Cohen was hired in August of that year and, to avoid confusion with the temple in Kilgore, Beth Shalom in Longview was renamed Temple Emanu-El in October. The synagogue had been in use for a few months prior to its dedication, hence the Longview Daily News’ September 15th, 1958 announcement that Rosh Hashanah services would be held at the synagogue, but a three day dedication service, featuring visiting rabbis from Beaumont and Tyler, Texas and Shreveport, Louisiana, was not held until November of 1958. The Longview Sunday News Journal editorialized on the final day of the dedication ceremonies that the construction of the synagogue “signifies growth and development of the [Longview] community to a stage of more substantial and mature permanence.” The editorial noted that the ceremony was open to the public and that civic and Christian leaders from Longview would be in attendance.

Jewish owned stores in Kilgore

Jewish owned stores in Kilgore closed for the high holidays in 1932

In 1963, Emanu-El hired Rabbi Charles Mantinband, who had caused controversy in his previous pulpit in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, for his outspoken support for civil rights. The leaders of Emanu-El requested that Mantinband tone down his civil rights activity prior to his arrival in Longview, which he apparently did. After eight years leading the Longview congregation, Mantinband’s age and loss of vision forced him to resign in 1971.

While Temple Emanu-El seemed to thrive in Longview, synagogues in surrounding towns, including Kilgore, fell on hard times in the 1960s and 1970s. Beth Sholom was maintained as a functioning congregation for about ten years following Emanu-El’s opening, but by the late 1960s Kilgore’s synagogue became vacant; the building’s roof caved in around 1973. Some of Beth Sholom’s members who had refused to join the new synagogue in Longview finally agreed to do so while others still stubbornly declined the opportunity to join their fellow Jews. The question remained, however, of what was to be done with Beth Sholom’s building as the structure sat severely dilapidated throughout the 1970’s. In 1979, Buster Dickerson, a local health store owner and real estate agent, bought the building, moving and converting it into an art studio. Dickerson transformed the former honky tonk and social hall into apartments. The funds from the sale of the synagogue were used for headstones for the Longview and Kilgore cemeteries, a scholarship for Jewish students at Kilgore College, and a sizable donation to Temple Emanu-El. When the Marshall Jewish community declined in the years after World War II, the city’s Moses Montefiore Congregation began to partner with Emanu-El. Jewish students from Marshall began attending Emanu-El’s sunday school in the 1960s. In 1971, the Marshall congregation closed down and sold its building, prompting many of Marshall’s Jews to join Emanu-El.

While Temple Emanu-El seemed to thrive in Longview, synagogues in surrounding towns, including Kilgore, fell on hard times in the 1960s and 1970s. Beth Sholom was maintained as a functioning congregation for about ten years following Emanu-El’s opening, but by the late 1960s Kilgore’s synagogue became vacant; the building’s roof caved in around 1973. Some of Beth Sholom’s members who had refused to join the new synagogue in Longview finally agreed to do so while others still stubbornly declined the opportunity to join their fellow Jews. The question remained, however, of what was to be done with Beth Sholom’s building as the structure sat severely dilapidated throughout the 1970’s. In 1979, Buster Dickerson, a local health store owner and real estate agent, bought the building, moving and converting it into an art studio. Dickerson transformed the former honky tonk and social hall into apartments. The funds from the sale of the synagogue were used for headstones for the Longview and Kilgore cemeteries, a scholarship for Jewish students at Kilgore College, and a sizable donation to Temple Emanu-El. When the Marshall Jewish community declined in the years after World War II, the city’s Moses Montefiore Congregation began to partner with Emanu-El. Jewish students from Marshall began attending Emanu-El’s sunday school in the 1960s. In 1971, the Marshall congregation closed down and sold its building, prompting many of Marshall’s Jews to join Emanu-El.

This stained glass sign from the Kilgore synagogue

This stained glass sign from the Kilgore synagogue is now on display at Temple Emanu-El in Longview

Civic Engagement

The Jews of Temple Emanu-El continued to serve their community as the first Jews to arrive in the area had done years before. Perhaps the best testament to how well Jews have been treated in Longview and Kilgore since their arrival has been the ease with which they have involved themselves in their community. G.A Bodenheim, M.H. Marwil and Charles Brachfield set the precedent for Jewish civic leadership in Longview’s surrounding area and Mrs. Sam Goldman, elected temporary chairman of Kilgore’s Literary Guild in 1935, continued their tradition. Hyman Hurwitz, known as “Mr. Kilgore,” served on various local and civic boards, including a stint as president of Chamber of Commerce, a position later held by Mendy Rabicoff. Hyman Laufer served as secretary of the Lion’s Club for almost 40 years, and many other Jewish families, including the Goldens, Finkelsteins, and Gertzes, distinguished themselves in both the Jewish and greater Kilgore and Longview communities.

The tradition of these men and women has left a lasting legacy. In June, 2011, Natalie Rabicoff , wife of Mendy, was named Citizen of the Year and received the prestigious Paul Harris Award from the Rotary Club of Longview in honor of her volunteer work, including her efforts to keep an Amtrak line in East Texas. Regarding the impact of Jews in Longview and Kilgore, a 1984 Longview Morning Journal article commemorating Temple Emanu-El’s 25th anniversary concluded: “The Jewish people of East Texas have always played an active part in the building of business, industry, and the communities of East Texas.”

The Jews of Temple Emanu-El continued to serve their community as the first Jews to arrive in the area had done years before. Perhaps the best testament to how well Jews have been treated in Longview and Kilgore since their arrival has been the ease with which they have involved themselves in their community. G.A Bodenheim, M.H. Marwil and Charles Brachfield set the precedent for Jewish civic leadership in Longview’s surrounding area and Mrs. Sam Goldman, elected temporary chairman of Kilgore’s Literary Guild in 1935, continued their tradition. Hyman Hurwitz, known as “Mr. Kilgore,” served on various local and civic boards, including a stint as president of Chamber of Commerce, a position later held by Mendy Rabicoff. Hyman Laufer served as secretary of the Lion’s Club for almost 40 years, and many other Jewish families, including the Goldens, Finkelsteins, and Gertzes, distinguished themselves in both the Jewish and greater Kilgore and Longview communities.

The tradition of these men and women has left a lasting legacy. In June, 2011, Natalie Rabicoff , wife of Mendy, was named Citizen of the Year and received the prestigious Paul Harris Award from the Rotary Club of Longview in honor of her volunteer work, including her efforts to keep an Amtrak line in East Texas. Regarding the impact of Jews in Longview and Kilgore, a 1984 Longview Morning Journal article commemorating Temple Emanu-El’s 25th anniversary concluded: “The Jewish people of East Texas have always played an active part in the building of business, industry, and the communities of East Texas.”

Temple Emanu-El in Longview

Temple Emanu-El in Longview

The Late 20th Century

Over the last decades of the 20th century, Temple Emanu-El, which had at least 75 families in the mid-1960s, faced questions about its future. Throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, the grown children of many of Longview and Kilgore’s Jews would return home for the High Holidays and at services the synagogue’s sanctuary would overflow. However, as many of the children raised in the congregation chose not to remain in East Texas moving to more metropolitan areas, the Jewish population of Kilgore and Longview has declined. By the late 1970s and 1980s many of the Jewish-owned stores had closed.

By the 1990s, this declining Jewish population and the interference of the Health Department ended a key synagogue fundraiser: Food-A-Rama. Members of the congregation would cook traditional Jewish foods to sell at the temple. The Health Department wanted all the food prepared in the small temple kitchen. Food-A-Rama had become a public event attended eagerly by both Jews and Gentiles; it even became an important campaign stop for local politicians.

Over the last decades of the 20th century, Temple Emanu-El, which had at least 75 families in the mid-1960s, faced questions about its future. Throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, the grown children of many of Longview and Kilgore’s Jews would return home for the High Holidays and at services the synagogue’s sanctuary would overflow. However, as many of the children raised in the congregation chose not to remain in East Texas moving to more metropolitan areas, the Jewish population of Kilgore and Longview has declined. By the late 1970s and 1980s many of the Jewish-owned stores had closed.

By the 1990s, this declining Jewish population and the interference of the Health Department ended a key synagogue fundraiser: Food-A-Rama. Members of the congregation would cook traditional Jewish foods to sell at the temple. The Health Department wanted all the food prepared in the small temple kitchen. Food-A-Rama had become a public event attended eagerly by both Jews and Gentiles; it even became an important campaign stop for local politicians.

The Jewish Community in Kilgore/Longview Today

The bimah at Temple Emanu-El

The bimah at Temple Emanu-El

While the population of Longview has witnessed significant growth in the last half century, rising from 40,050 in 1960 to 73,344 in 2000, the membership of Emanu-El has dwindled with the decline of the Jewish populations of Longview and Kilgore. In 2011, Emanu-El has around 30 members, 18 of whom remain active. Emanu-El’s last full-time rabbi was Bernard Honan, who served in Longview until around 1996. Since then, the congregation has relied on visiting rabbis and lay leaders.

In the 1930s, as oil derricks shot up rapidly along the East Texas horizon, Jewish businesses and a small synagogue in Kilgore shot up as well. That synagogue soon grew, and became Longview’s Emanu-El, a sustaining lifeline of organized Judaism for residents of many surrounding towns. Many of East Texas’ oil derricks are no longer standing, but Temple Emanu-El is, and, despite its recent struggles, hopes to continue doing so for years to come.

In the 1930s, as oil derricks shot up rapidly along the East Texas horizon, Jewish businesses and a small synagogue in Kilgore shot up as well. That synagogue soon grew, and became Longview’s Emanu-El, a sustaining lifeline of organized Judaism for residents of many surrounding towns. Many of East Texas’ oil derricks are no longer standing, but Temple Emanu-El is, and, despite its recent struggles, hopes to continue doing so for years to come.