Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Biloxi-Gulfport, Mississippi

Overview >> Mississippi >> Biloxi-Gulfport

|

Historical Overview

The Jewish community of Biloxi-Gulfport is one of both the oldest and the newest in Mississippi. While the first sign of organized Jewish life on the Mississippi Gulf Coast dates from the 1850s, the area did not have a Jewish congregation until the 1950s. Since then, Biloxi-Gulfport has supported a small but active Jewish population whose history is unique among the Jewish communities of Mississippi.

For millennia, human activity in the area depended on the natural resources found in the Gulf of Mexico. American Indian groups harvested oysters, flounder, and other food sources from the gulf and its estuaries more than 3,000 years before European contact. The French first settled Biloxi in 1699, and for a short time it was the capital of French Louisiana. The ebbs and flows of Jewish life on the Mississippi coast reflect the region’s distinct identity and maritime industries, as the area’s economy and culture have as much in common with coastal regions of Alabama and Louisiana as with inland Mississippi. Likewise, the local Jewish community has maintained closer ties to New Orleans and Mobile than to other Mississippi towns. In the early 21st century, Biloxi and its neighbor Gulfport are the central population center of the Mississippi Gulf Coast. |

"Historical Landmark, Original Jewish Biloxi Jewish Cemetery—one of the oldest Jewish cemeteries in the South—established 1855."

"Historical Landmark, Original Jewish Biloxi Jewish Cemetery—one of the oldest Jewish cemeteries in the South—established 1855."

Biloxi Hebrew Rest Cemetery

The earliest sign of a permanent Jewish settlement in the area was the creation of a Jewish cemetery called “Hebrew Rest” in 1853. Located on Reynoir Street in Biloxi, and not used for decades, this cemetery was purchased by Jews in New Orleans, most likely the Gates of Mercy Synagogue. Frederick Reynoir deeded the land to L. Klopman of the “Hebrew Society of the City of New Orleans to be used as a burying ground until there shall be a synagogue in Biloxi.” The Gates of Mercy congregation already had a cemetery in 1853, and the most probable explanation for their purchase was that year's yellow fever epidemic in New Orleans. During the outbreak, many of the city’s residents fled to safer areas, including places like Biloxi. Thus, the congregation likely purchased Hebrew Rest cemetery for Jews who evacuated New Orleans but died in Biloxi. Although the exact number of burials is unclear, most estimates of the number of Hebrew Rest gravesites range from 10 to 20.

By 1916, the city took control of the abandoned land of Hebrew Rest. When the municipal government widened Reynoir Street, they planned to move many of the tombs to the naval reserve. The city issued notice to the families of Cecile Schwartz, Oury Bernard, Aaron Cohen, Mrs. Mathilda Harnthal, Henry Lyons, Lazarius Leopold, Brandly Friedlander, and Michel Levy, warning them of the possible displacement of their family graves, though it is unclear whether these graves were ever disinterred.

The earliest sign of a permanent Jewish settlement in the area was the creation of a Jewish cemetery called “Hebrew Rest” in 1853. Located on Reynoir Street in Biloxi, and not used for decades, this cemetery was purchased by Jews in New Orleans, most likely the Gates of Mercy Synagogue. Frederick Reynoir deeded the land to L. Klopman of the “Hebrew Society of the City of New Orleans to be used as a burying ground until there shall be a synagogue in Biloxi.” The Gates of Mercy congregation already had a cemetery in 1853, and the most probable explanation for their purchase was that year's yellow fever epidemic in New Orleans. During the outbreak, many of the city’s residents fled to safer areas, including places like Biloxi. Thus, the congregation likely purchased Hebrew Rest cemetery for Jews who evacuated New Orleans but died in Biloxi. Although the exact number of burials is unclear, most estimates of the number of Hebrew Rest gravesites range from 10 to 20.

By 1916, the city took control of the abandoned land of Hebrew Rest. When the municipal government widened Reynoir Street, they planned to move many of the tombs to the naval reserve. The city issued notice to the families of Cecile Schwartz, Oury Bernard, Aaron Cohen, Mrs. Mathilda Harnthal, Henry Lyons, Lazarius Leopold, Brandly Friedlander, and Michel Levy, warning them of the possible displacement of their family graves, though it is unclear whether these graves were ever disinterred.

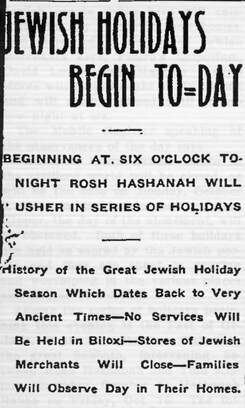

A local newspaper notice about the High Holy Days. The Daily Herald (Biloxi), September 25, 1908.

A local newspaper notice about the High Holy Days. The Daily Herald (Biloxi), September 25, 1908.

Early 20th Century

During the several decades after the founding of the cemetery, a few Jewish families lived on the Gulf Coast but never in enough concentration to form a congregation. Most of these Jews owned retail stores. In 1908, the local newspaper noted that there would be no Jewish services for the high holidays in the area since there was no congregation, though "doubtless, Jewish people living here will celebrate the day quietly in their homes." The handful of Jewish-owned stores in town, including Picard's Emporium and David and Maurice Levy's stores, did close for the Jewish holidays that year.

Area Jews attempted to organize themselves in 1925, with assistance from Rabbi Alfred S. Moses, of Mobile, who had been stationed in Gulfport during World War I. Biloxi Jews formed the Jewish Coast Society, with leadership from Phillip Levine, I.B. Rau, and Sophie Schwartz. The group does not seem to have been very active, and the local Jewish population grew slowly. Those who wanted to worship with a congregation traveled to either New Orleans or Mobile to attend synagogue.

As late as 1937, only 41 Jews lived in Biloxi/Gulfport. During the 1930s, Jews owned at least three stores in Biloxi and Gulfport, including a furniture store owned by the Cohens, a ladies’ clothing store owned by I. B. Rau, and the Rosenbloom Clothing Store owned by James Rosenbloom. The Grishman family also arrived in the area from New Orleans in the early 1930s, when Ben Grishman and his son Moody ran a small farm north of Gulfport. Moody spent about a decade on the farm, lived in New Orleans for several years, and then returned to the Gulf Coast with his family in the late 1940s.

During the several decades after the founding of the cemetery, a few Jewish families lived on the Gulf Coast but never in enough concentration to form a congregation. Most of these Jews owned retail stores. In 1908, the local newspaper noted that there would be no Jewish services for the high holidays in the area since there was no congregation, though "doubtless, Jewish people living here will celebrate the day quietly in their homes." The handful of Jewish-owned stores in town, including Picard's Emporium and David and Maurice Levy's stores, did close for the Jewish holidays that year.

Area Jews attempted to organize themselves in 1925, with assistance from Rabbi Alfred S. Moses, of Mobile, who had been stationed in Gulfport during World War I. Biloxi Jews formed the Jewish Coast Society, with leadership from Phillip Levine, I.B. Rau, and Sophie Schwartz. The group does not seem to have been very active, and the local Jewish population grew slowly. Those who wanted to worship with a congregation traveled to either New Orleans or Mobile to attend synagogue.

As late as 1937, only 41 Jews lived in Biloxi/Gulfport. During the 1930s, Jews owned at least three stores in Biloxi and Gulfport, including a furniture store owned by the Cohens, a ladies’ clothing store owned by I. B. Rau, and the Rosenbloom Clothing Store owned by James Rosenbloom. The Grishman family also arrived in the area from New Orleans in the early 1930s, when Ben Grishman and his son Moody ran a small farm north of Gulfport. Moody spent about a decade on the farm, lived in New Orleans for several years, and then returned to the Gulf Coast with his family in the late 1940s.

A Growing Jewish Population and a New Congregation

World War II was a watershed event for Biloxi and its Jewish community. The opening of Keesler Air Force Base brought new life to the Jewish population of Biloxi, as well as vigor to the economy. The arrival of new Jewish residents stoked demand for organized worship. Newcomers such as Abe Silver were the catalyst in the founding of new Jewish institutions. Silver moved to Biloxi to work as an electronics instructor on the base and served for many years as a lay leader, leading Shabbat and High Holiday services and conducting weddings and funerals. Other Beth Israel members lured to Biloxi by the base included Charles Gottesman, Fran Leitner, Zelma Feldman, and Len Fishman.

World War II was a watershed event for Biloxi and its Jewish community. The opening of Keesler Air Force Base brought new life to the Jewish population of Biloxi, as well as vigor to the economy. The arrival of new Jewish residents stoked demand for organized worship. Newcomers such as Abe Silver were the catalyst in the founding of new Jewish institutions. Silver moved to Biloxi to work as an electronics instructor on the base and served for many years as a lay leader, leading Shabbat and High Holiday services and conducting weddings and funerals. Other Beth Israel members lured to Biloxi by the base included Charles Gottesman, Fran Leitner, Zelma Feldman, and Len Fishman.

Local Jews founded a B’nai B’rith Lodge in 1953 under the encouragement of Max Signoff of Hattiesburg, who believed the fraternal organization would bring together the disconnected Jewish population of the Gulf Coast. The group drew members from Biloxi, Gulfport, Long Beach, and Pascagoula. One of their early projects was an effort to restore the old cemetery. They faced a difficult task; the cemetery had been severely desecrated, and some of the tombstones were even being used as doorsteps throughout Biloxi. The preservation effort was further disrupted when the city built Elder Street on top of the cemetery site, cutting directly through the burial grounds. In response, the Beth Israel Congregation (established 1958) constructed a fence around the site to demarcate it from the surrounding forest and erected a historical marker to commemorate the cemetery. One of the project’s successes was the restoration of the grave of Michel Levy. Levy, who had been born in Paris, France, had lived in Biloxi only three months before he died of “bilious remittent fever” at age 17 and was buried in Hebrew Rest. The Gulf Coast B'nai B'rith was also engaged with the larger Gulf Coast community—in 1969, when Hurricane Camille decimated the Mississippi coast, the Gulf Coast B’nai B’rith lodge raised money for the recovery effort and donated a mobile headquarters to the Salvation Army and Red Cross to aid in the clean up.

As the Gulf Coast Jewish population grew in the post-war years, the local community also held Shabbat evening services at Keesler Air Force Base, where Jewish chaplains often led worship. Community members Rubin Goldin, Jack Goldin, Abe Herman, Dave Rosenblum, and Moody Grishman led efforts to secure a building, but the small Jewish population struggled to raise the necessary funds for several years. Then Congregation Beth Israel received its official charter in 1958, acquired a building in the same year, and dubbed it the Jewish Community Center of Congregation Beth Israel. The community center was a converted home, which the congregation bought for $8,000 after a fire caused extensive damage to the structure. After purchase, Congregation Beth Israel spent an additional $6,000 to repair the space and convert it according to their needs.

Officers of the new congregation included Abraham H. Silver (president), Rubin Goldin (vice-president), Gerald Piltz (treasurer), and Bernard Horn (secretary). In order to accommodate a range of Jewish practices, the bylaws of the Congregation provided that the worship services would follow Conservative Judaism, making it the only Conservative synagogue in the state of Mississippi.

The fact that the Jews of Biloxi called their building a Jewish Community Center rather than simply a synagogue reflects their desire to cater to all the needs of the Jewish community under a single roof. The move also fit the national trend of rethinking the traditional “shul” as a “synagogue center.” Prior to construction of the building, the Jewish community of the Mississippi Gulf Coast had been isolated and disjointed. Jews in coastal towns were often unaware of the existence of other Jewish families in their area. The building was designed to address that issue by creating social and community bonds based on ethnic as well as religious commonalities. In the early days of the Community Center, they even hoped to build a swimming pool and tennis courts to help the children to socialize with one another.

Nearly all the Jews in Biloxi contributed labor and/or finances to the project. Arthur Nathanson and his mother, Mrs. Ethel Nathanson of Chicago, worked together to arrange the donation of a Torah scroll and ark from their Chicago congregation. Rabbi Charles Mantinband of Hattiesburg led services at the synagogue’s dedication. There were reportedly 200 people in attendance, including visitors from New Orleans and Hattiesburg. After the building’s initial rehabilitation, an additional wing was erected in the early 1960s for a larger sanctuary. The Beth Israel Sisterhood organized religious school classes for the congregation’s children.

As the Gulf Coast Jewish population grew in the post-war years, the local community also held Shabbat evening services at Keesler Air Force Base, where Jewish chaplains often led worship. Community members Rubin Goldin, Jack Goldin, Abe Herman, Dave Rosenblum, and Moody Grishman led efforts to secure a building, but the small Jewish population struggled to raise the necessary funds for several years. Then Congregation Beth Israel received its official charter in 1958, acquired a building in the same year, and dubbed it the Jewish Community Center of Congregation Beth Israel. The community center was a converted home, which the congregation bought for $8,000 after a fire caused extensive damage to the structure. After purchase, Congregation Beth Israel spent an additional $6,000 to repair the space and convert it according to their needs.

Officers of the new congregation included Abraham H. Silver (president), Rubin Goldin (vice-president), Gerald Piltz (treasurer), and Bernard Horn (secretary). In order to accommodate a range of Jewish practices, the bylaws of the Congregation provided that the worship services would follow Conservative Judaism, making it the only Conservative synagogue in the state of Mississippi.

The fact that the Jews of Biloxi called their building a Jewish Community Center rather than simply a synagogue reflects their desire to cater to all the needs of the Jewish community under a single roof. The move also fit the national trend of rethinking the traditional “shul” as a “synagogue center.” Prior to construction of the building, the Jewish community of the Mississippi Gulf Coast had been isolated and disjointed. Jews in coastal towns were often unaware of the existence of other Jewish families in their area. The building was designed to address that issue by creating social and community bonds based on ethnic as well as religious commonalities. In the early days of the Community Center, they even hoped to build a swimming pool and tennis courts to help the children to socialize with one another.

Nearly all the Jews in Biloxi contributed labor and/or finances to the project. Arthur Nathanson and his mother, Mrs. Ethel Nathanson of Chicago, worked together to arrange the donation of a Torah scroll and ark from their Chicago congregation. Rabbi Charles Mantinband of Hattiesburg led services at the synagogue’s dedication. There were reportedly 200 people in attendance, including visitors from New Orleans and Hattiesburg. After the building’s initial rehabilitation, an additional wing was erected in the early 1960s for a larger sanctuary. The Beth Israel Sisterhood organized religious school classes for the congregation’s children.

Milton and Moody Grishman, c. 1992. Bill Aron.

Milton and Moody Grishman, c. 1992. Bill Aron.

Moody Grishman (right)was a leader in the consolidation of the Jewish community in the 1950s. He found the site for Beth Israel’s synagogue. In his youth he began farming on a forty acre farm in Gulfport, raising dairy cows and chickens as well as producing onions, pecans, and vegetables. When Grishman returned to the coast in the late 1940s, he initially owned a restaurant on the beach in Mississippi City. He raised four children with his wife, Elizabeth Cowan Grishman. Only their son Milt Grishman (left) settled in the area as an adult.

The Late 20th Century

Though Beth Israel never employed a full-time rabbi, the congregation continued regular shabbat and holiday services under lay leadership for almost fifty years in the original synagogue on the northwest corner of Southern Avenue and Camellia Street. The congregation has benefited over the years from Jewish chaplains at Keesler Air Force Base and, more recently, from visiting student rabbis arranged through the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism and the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York City.

The Gulf Coast Jewish community remained small, but close-knit through the 1980s. Biloxi-Gulfport had about 100 Jews in 1984. In the 1990s, the area was transformed yet again by legalized gambling. Large casinos and hotels sprung up on the beaches in Biloxi and Gulfport. The new tourism business attracted Jews from other parts of the country to the Mississippi coast. Steve Richer came from New Jersey in the 1990s to become the executive director of the Mississippi Gulf Coast Convention & Visitors Bureau. He eventually became president of Beth Israel and led the congregation during the hardships of Hurricane Katrina. In 2001, 250 Jews lived in the area. Journalist and editor Lori Beth Susman also moved to Gulfport in the 1990s and works for a gaming industry magazine. She is a past president of Congregation Beth Israel and remains an active leader in the congregation more than twenty years after her arrival.

Hurricane Katrina and Its Aftermath

The local Jewish community was still growing when Hurricane Katrina struck the Louisiana and Mississippi coasts in 2005. The storm brought unprecedented destruction to the area, and the Jewish community suffered its share. Their synagogue, located just blocks from the beach in Biloxi, received major damage to its roof and facade. The storm destroyed the homes of 13 member families out of a total of roughly 65 households, and almost every member of the community was at least temporarily displaced. Only a handful of members left the area following the disaster, however, and the congregation began to hold services at Keesler Air Force Base and Beauvoir United Methodist Church as they decided how to move forward.

Despite the damage to the synagogue, Congregation Beth Israel did save several of its most important belongings. The building’s custodian, Mark Tebor, managed to protect the Torah scroll by moving it to a safe location before the storm hit. Afterward, high school student and congregant Russell Goldin organized a salvage effort for his Eagle Scout project. Goldin’s Boy Scout Troop donned masks and gloves in order to remove Judaica from the building, catalog the objects, and place them in temporary storage. After the congregation made the difficult choice of building a new synagogue in Gulfport, they were able to install stained glass windows and memorial plaques that had survived the disaster. They dedicated the new building on the holiday of Shavuot in May 2009.

The local Jewish community was still growing when Hurricane Katrina struck the Louisiana and Mississippi coasts in 2005. The storm brought unprecedented destruction to the area, and the Jewish community suffered its share. Their synagogue, located just blocks from the beach in Biloxi, received major damage to its roof and facade. The storm destroyed the homes of 13 member families out of a total of roughly 65 households, and almost every member of the community was at least temporarily displaced. Only a handful of members left the area following the disaster, however, and the congregation began to hold services at Keesler Air Force Base and Beauvoir United Methodist Church as they decided how to move forward.

Despite the damage to the synagogue, Congregation Beth Israel did save several of its most important belongings. The building’s custodian, Mark Tebor, managed to protect the Torah scroll by moving it to a safe location before the storm hit. Afterward, high school student and congregant Russell Goldin organized a salvage effort for his Eagle Scout project. Goldin’s Boy Scout Troop donned masks and gloves in order to remove Judaica from the building, catalog the objects, and place them in temporary storage. After the congregation made the difficult choice of building a new synagogue in Gulfport, they were able to install stained glass windows and memorial plaques that had survived the disaster. They dedicated the new building on the holiday of Shavuot in May 2009.

The Jewish Community in Biloxi/Gulfport Today

As of 2021, Congregation Beth Israel maintains an active schedule, although its membership has declined to approximately 60. Congregants point out that the new synagogue’s residential design matches the community’s heymish (homey) feel. The congregation hired its first full-time rabbi in 2020, when the congregation voted (in a contested decision) to hire the local Chabad rabbi, Akiva Hall and his wife, Hannah Hall, who directs the religious school. The congregation subsequently ended its affiliation with the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism and instituted some ritual changes, including separate seating for men and women in the sanctuary. Despite his new role, Rabbi Hall was already a familiar figure at the congregation; he grew up in nearby Ocean Springs and attended Beth Israel in high school. Following ordination and marriage, Hall returned to the Mississippi Gulf Coast in 2014 as the state’s only Chabad emissary. According to members of Congregation Beth Israel, Hall’s local roots and considerate approach made the merger more palatable for some congregants, and the two groups had collaborated frequently in the lead-up to Rabbi Hall's hire. Jewish children from the Goldin family, for instance, studied Hebrew with Rabbi Hall’s wife, Hannah, but also attended religious school at Congregation Beth Israel.

Local Jews remain active in the wider community, as volunteers, boosters, and civic leaders. Ryan Goldin serves as both president of Congregation Beth Israel and chair of the Gulfport Chamber of Commerce. The Jewish community of the early-21st-century Mississippi Gulf Coast reflects its relatively recent origins—a small and tight-knit community whose future will depend on the economic conditions and demographic patterns of the local area.

Local Jews remain active in the wider community, as volunteers, boosters, and civic leaders. Ryan Goldin serves as both president of Congregation Beth Israel and chair of the Gulfport Chamber of Commerce. The Jewish community of the early-21st-century Mississippi Gulf Coast reflects its relatively recent origins—a small and tight-knit community whose future will depend on the economic conditions and demographic patterns of the local area.

Selected Bibliography

James F. Barnett Jr., Mississippi’s American Indians (Oxford, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi, 2012).

“Biloxi’s Jewish Community,” Biloxi Historical Society.

Aimee L. Schmidt, “Down Around Biloxi: An Overview of Ethnic and Occupational Identity in a Coastal Town,” Ethnic Heritage in Mississippi: The Twentieth Century (Oxford, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi, 2012).

Josh Tapper, “10 years on, Katrina echoes for Mississippi Jews,” Jewish Telegraphic Agency, August 16, 2015.

James F. Barnett Jr., Mississippi’s American Indians (Oxford, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi, 2012).

“Biloxi’s Jewish Community,” Biloxi Historical Society.

Aimee L. Schmidt, “Down Around Biloxi: An Overview of Ethnic and Occupational Identity in a Coastal Town,” Ethnic Heritage in Mississippi: The Twentieth Century (Oxford, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi, 2012).

Josh Tapper, “10 years on, Katrina echoes for Mississippi Jews,” Jewish Telegraphic Agency, August 16, 2015.