Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Mobile, Alabama

Overview

During its 300 years of existence, Mobile has been a part of French Louisiana, British West Florida, and now, Alabama. While today Mobile has only the third largest Jewish population in the state, behind Birmingham and Montgomery, during the antebellum period it was the center of Jewish life in Alabama.

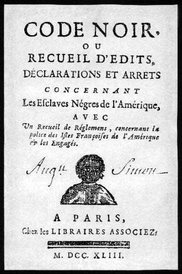

Mobile was founded in 1702 as the capital of the French colonial possession Louisiana. Mobile passed through both British and Spanish hands before it became part of the United States in 1813. Being the only sea port in Alabama, Mobile experienced much shipping traffic and an influx of travelers. The Port of Mobile was a key trading center between the French and Native Americans when Mobile was still a part of Louisiana and attracted many travelers and merchants from New Orleans. Before the Civil War, the Port of Mobile became a major trading center for cotton and the enslaved African American workers who raised and picked it. Slaves arrived by ship in Mobile Bay and departed with their new owners on the Alabama River. Cotton was shipped down the river from both Alabama and Mississippi and sent around the country and the world. Jews did not begin to appear in Mobile until after 1763 when the territory was turned over to the British. As a result of the Code Noir, which expelled all Jews from the French colonies and banned them from owning property or slaves, few Jews lived in Mobile during the French occupation. New Orleans promised better opportunities for commercial undertakings, so more Jews settled there. Until 1841, when Jews purchased land for a cemetery, there was not much of a Jewish community in Mobile. Indeed, until 1841, the history of Jews in Mobile was mainly a history of individuals. These resourceful and skilled men were well integrated into the economic and social life of Mobile; they often married Christian women because there were no Jewish women in the area. In the middle of the 19th century, a Jewish community began to form, growing into a robust community that lasts today. |

Stories of the Jewish Community in Mobile

Early Settlers

The early Mobile Jewish population was comprised of many interesting characters. A man named Judah was an actor and gave dramatic readings in Mobile and Montgomery. He soon started a theatrical company in Mobile and put on acclaimed performances of Shakespeare. Since such theatrical work did not pay a sufficient amount, Judah also opened his own school in 1822. Solomon Mordecai arrived in Mobile in 1823 and became a well-respected physician in the community.

A few years later, Isaac Lazarus, who had been the shochet at Congregation Mikveh Israel in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, came to Mobile with his brother Sol and opened a store. The Lazarus brothers also bought and sold land and marketed patent medicines. Isaac was perhaps better at slaughtering kosher meat than he was at business, since 640 acres of his land was auctioned off in 1828 for non-payment of debts.

Many of these early Mobile Jews played an important role in civic and political affairs. In 1830, Solomon Jones moved to Mobile and became a very successful merchant. Jones was quite active in the town’s civic affairs, serving as a volunteer fireman, an alderman, port warden, and rising to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel in the Alabama State Militia. Solomon’s brother, Israel Jones, also served on the city council and was briefly the acting mayor of Mobile. Jacob Cohen, who had only arrived in 1839, was elected City Marshall in 1841 and 1842. Adolph Proskauer, who rose to the rank of Major in the Confederate Army, served in the State Legislature during Reconstruction. At a time when Jews still faced restrictions against holding public office in other states, the political careers of these Mobile Jews were quite extraordinary.

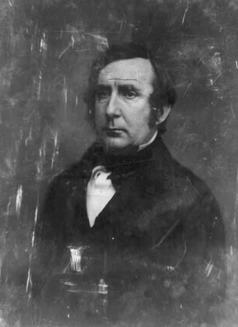

One of the most respected members of this early Mobile Jewish community was attorney Philip Phillips, who came to Alabama from South Carolina in 1835. Phillips got involved in politics, serving in Alabama’s State Legislature and the U.S. House of Representatives as a Democrat. While in congress, Phillips was largely responsible for the controversial provision of the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 which repealed the earlier Missouri Compromise, an agreement that had prohibited slavery in much of the Louisiana territory. Although Phillips was a Southerner, he was Unionist and remained in Washington after the Civil War began. His wife Eugenia Levy was a staunch Confederate sympathizer, and Eugenia Levy Phillips was even arrested for espionage before Phillips used his political connections to get her released. The family then moved to New Orleans in August of 1861. After the North captured the Crescent City, Eugenia was arrested again after failing to pay proper respect to a Union soldier’s passing funeral cortege. When she was released three months later, the family went to La Grange, Georgia, where they spent the remainder of the war. After the war, Phillip Phillips moved back to Washington where he continued to practice law, pleading more than four hundred cases before the U.S. Supreme Court.

The early Mobile Jewish population was comprised of many interesting characters. A man named Judah was an actor and gave dramatic readings in Mobile and Montgomery. He soon started a theatrical company in Mobile and put on acclaimed performances of Shakespeare. Since such theatrical work did not pay a sufficient amount, Judah also opened his own school in 1822. Solomon Mordecai arrived in Mobile in 1823 and became a well-respected physician in the community.

A few years later, Isaac Lazarus, who had been the shochet at Congregation Mikveh Israel in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, came to Mobile with his brother Sol and opened a store. The Lazarus brothers also bought and sold land and marketed patent medicines. Isaac was perhaps better at slaughtering kosher meat than he was at business, since 640 acres of his land was auctioned off in 1828 for non-payment of debts.

Many of these early Mobile Jews played an important role in civic and political affairs. In 1830, Solomon Jones moved to Mobile and became a very successful merchant. Jones was quite active in the town’s civic affairs, serving as a volunteer fireman, an alderman, port warden, and rising to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel in the Alabama State Militia. Solomon’s brother, Israel Jones, also served on the city council and was briefly the acting mayor of Mobile. Jacob Cohen, who had only arrived in 1839, was elected City Marshall in 1841 and 1842. Adolph Proskauer, who rose to the rank of Major in the Confederate Army, served in the State Legislature during Reconstruction. At a time when Jews still faced restrictions against holding public office in other states, the political careers of these Mobile Jews were quite extraordinary.

One of the most respected members of this early Mobile Jewish community was attorney Philip Phillips, who came to Alabama from South Carolina in 1835. Phillips got involved in politics, serving in Alabama’s State Legislature and the U.S. House of Representatives as a Democrat. While in congress, Phillips was largely responsible for the controversial provision of the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 which repealed the earlier Missouri Compromise, an agreement that had prohibited slavery in much of the Louisiana territory. Although Phillips was a Southerner, he was Unionist and remained in Washington after the Civil War began. His wife Eugenia Levy was a staunch Confederate sympathizer, and Eugenia Levy Phillips was even arrested for espionage before Phillips used his political connections to get her released. The family then moved to New Orleans in August of 1861. After the North captured the Crescent City, Eugenia was arrested again after failing to pay proper respect to a Union soldier’s passing funeral cortege. When she was released three months later, the family went to La Grange, Georgia, where they spent the remainder of the war. After the war, Phillip Phillips moved back to Washington where he continued to practice law, pleading more than four hundred cases before the U.S. Supreme Court.

Organized Jewish Life in Mobile

As more Jews settled in Mobile, they began to build community institutions. In 1841, local Jews purchased land for $30 for use as a cemetery. In 1844, they formally created Alabama’s first congregation, Shaarai Shomayim (Gates of Heaven). By 1846, the congregation, now numbering fifty members, had acquired its first synagogue, a former church located on St. Emanuel Street. Benjamin da Silva, who led services in the Sephardic style, was the first rabbi. Since most congregants were of German descent, they were unsatisfied praying in the Sephardic tradition. In 1853, when the congregation set out to look for a new rabbi, it published an advertisement announcing that “the worship is conducted according to the forms of the German Minhag, the reader must be competent to deliver in English, and a preference would be given to one capable of delivering them also in German.”

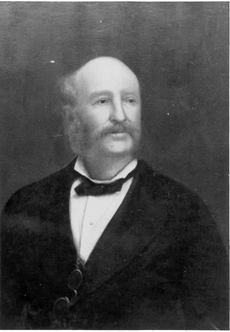

Israel Jones became the recognized leader of Mobile’s growing Jewish community, serving as president of the congregation for over thirty years. In 1860, he was elected as vice president to the first nationally organized American Jewish assembly, the Board of Delegates of American Israelites. This was quite a feat considering Mobile’s relatively small size. In 1853, the congregation moved to a new building on Jackson Street. Representatives from Protestant and Catholic churches were present as guests at the dedication ceremony, becoming part of a long history of interfaith cooperation between Sha’arai Shomayim and the Christian community of Mobile. When a fire destroyed this building in 1856, several non-Jewish residents of Mobile contributed money to the rebuilding effort. By 1858 a new synagogue had been dedicated on Jackson Street.

The fire wasn’t the only turmoil the congregation faced. Tensions within the congregation had been growing over the issue of using the Ashkenazi or the Sephardic rite during services. This dispute came to a head in 1855 when a segment of the congregation broke off to form a new congregation called Dorshey Zedek (Seekers of Justice). Sixty members remained with the Jackson Street synagogue while thirty members split off to form the new congregation. The members of Dorshey Zedek gathered to pray in a firehouse. This split was short-lived, as by 1859 the two congregations reunited.

As more Jews settled in Mobile, they began to build community institutions. In 1841, local Jews purchased land for $30 for use as a cemetery. In 1844, they formally created Alabama’s first congregation, Shaarai Shomayim (Gates of Heaven). By 1846, the congregation, now numbering fifty members, had acquired its first synagogue, a former church located on St. Emanuel Street. Benjamin da Silva, who led services in the Sephardic style, was the first rabbi. Since most congregants were of German descent, they were unsatisfied praying in the Sephardic tradition. In 1853, when the congregation set out to look for a new rabbi, it published an advertisement announcing that “the worship is conducted according to the forms of the German Minhag, the reader must be competent to deliver in English, and a preference would be given to one capable of delivering them also in German.”

Israel Jones became the recognized leader of Mobile’s growing Jewish community, serving as president of the congregation for over thirty years. In 1860, he was elected as vice president to the first nationally organized American Jewish assembly, the Board of Delegates of American Israelites. This was quite a feat considering Mobile’s relatively small size. In 1853, the congregation moved to a new building on Jackson Street. Representatives from Protestant and Catholic churches were present as guests at the dedication ceremony, becoming part of a long history of interfaith cooperation between Sha’arai Shomayim and the Christian community of Mobile. When a fire destroyed this building in 1856, several non-Jewish residents of Mobile contributed money to the rebuilding effort. By 1858 a new synagogue had been dedicated on Jackson Street.

The fire wasn’t the only turmoil the congregation faced. Tensions within the congregation had been growing over the issue of using the Ashkenazi or the Sephardic rite during services. This dispute came to a head in 1855 when a segment of the congregation broke off to form a new congregation called Dorshey Zedek (Seekers of Justice). Sixty members remained with the Jackson Street synagogue while thirty members split off to form the new congregation. The members of Dorshey Zedek gathered to pray in a firehouse. This split was short-lived, as by 1859 the two congregations reunited.

Sha’arai Shomayim continued to face hardships after the Civil War. Located on the water, Mobile often suffered disease outbreaks, especially the dreaded yellow fever. In 1870, yellow fever swept through the town. Most Mobile citizens who were able to leave the city did so. Rabbi Abraham Laser of Sha’arai Shomayim decided to stay in the city to minister to the sick and dying. He later contracted the disease himself and died, becoming the first rabbi to be buried in Magnolia Cemetery.

Around the time of the Civil War, the congregation established a religious school with classes being held every weekday except Friday. Sixty students attended the school at its peak. When the war ended in 1865, Sha’arai Shomayim established a day school that taught both religious and secular subjects. The school remained in operation until 1878 when the Mobile Public School System became tuition-free, at which point Sha’arai Shomayim’s school offered a purely religious education.

In addition to an active religious school, Sha’arai Shomayim had a strong musical component to its worship services, thank to the German-born Joseph Bloch and Sigmund Schlesinger. Bloch was the music director at Jesuit Spring Hill College and opened Mobile’s first music store. Under his guidance, an organ was introduced to services. Schlesinger served the congregation as organist and choir leader for forty-nine years until his death in 1906. Schlesinger’s compositions were adopted by many Reform congregations around the country.

Around the time of the Civil War, the congregation established a religious school with classes being held every weekday except Friday. Sixty students attended the school at its peak. When the war ended in 1865, Sha’arai Shomayim established a day school that taught both religious and secular subjects. The school remained in operation until 1878 when the Mobile Public School System became tuition-free, at which point Sha’arai Shomayim’s school offered a purely religious education.

In addition to an active religious school, Sha’arai Shomayim had a strong musical component to its worship services, thank to the German-born Joseph Bloch and Sigmund Schlesinger. Bloch was the music director at Jesuit Spring Hill College and opened Mobile’s first music store. Under his guidance, an organ was introduced to services. Schlesinger served the congregation as organist and choir leader for forty-nine years until his death in 1906. Schlesinger’s compositions were adopted by many Reform congregations around the country.

Sha’arai Shomayim had embraced Reform Judaism, as demonstrated by the use of Bloch and Schlesinger's music in services. In 1873, the congregation became one of the charter members of the Reform Union of American Hebrew Congregations (UAHC). They had a close relationship with Isaac Mayer Wise, the founder of the UAHC and the Hebrew Union College (HUC). In 1883, Sha’arai Shomayim hired one of the first graduates of Wise’s Reform seminary, Henry Berkowitz, who was in HUC’s inaugural class. Rabbi Berkowitz served Sha’arai Shomayim for five years before moving on to a pulpit in Kansas City. Berkowitz went on to become one of the most prominent Reform rabbis in America, serving Philadelphia’s Rodeph Shalom congregation for thirty years.

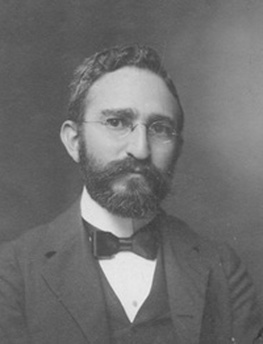

In 1901, Sha’arai Shomayim hired another promising young graduate of Hebrew Union College, Alfred Geiger Moses, who went on to have a long and notable career at the congregation. Influenced by the rise of Christian Science, and seeking to head off a growing interest in that religion by Reform Jews, Rabbi Moses sought to revitalize Reform Judaism in America. According to the scholar Ellen Umansky, Moses put forth the idea of a Jewish mission by creating a counter-vision of happiness and health set within the Jewish faith. In his sermons, Rabbi Moses stressed the importance of “spiritual Judaism” and divine healing. He went on to publish his own critique of Christian Science in a book he titled “Jewish Science.” Moses ultimately encouraged his readers and congregants to incorporate personal goals of health, success, and happiness within their own understanding of Reform’s ethical monotheism. Rabbi Moses served Sha’arai Shomayim for almost forty years, retiring in 1940.

Mobile Jews maintained their own social institutions even as they assimilated to the local culture. The men of Sha’arai Shomayim founded the Fidelia Club in the 1880s. The group built a clubhouse on the corner of Government and Washington Streets, which became the site for many social events in the Mobile Jewish community as well as innumerable card games. Most of the Fidelia Club’s members were part of Mobile’s old German-Jewish families. The Fidelia Club closed in the early years of the Great Depression. In 1891, Mobile Jews also formed their own Mardi Gras Society called the Continental Mystic Crewe, which threw an annual masked ball in conjunction with the city’s Mardi Gras celebration. The group disbanded in 1913, although other Jewish Mardi Gras groups continued to hold lavish annual balls until 1922.

In 1901, Sha’arai Shomayim hired another promising young graduate of Hebrew Union College, Alfred Geiger Moses, who went on to have a long and notable career at the congregation. Influenced by the rise of Christian Science, and seeking to head off a growing interest in that religion by Reform Jews, Rabbi Moses sought to revitalize Reform Judaism in America. According to the scholar Ellen Umansky, Moses put forth the idea of a Jewish mission by creating a counter-vision of happiness and health set within the Jewish faith. In his sermons, Rabbi Moses stressed the importance of “spiritual Judaism” and divine healing. He went on to publish his own critique of Christian Science in a book he titled “Jewish Science.” Moses ultimately encouraged his readers and congregants to incorporate personal goals of health, success, and happiness within their own understanding of Reform’s ethical monotheism. Rabbi Moses served Sha’arai Shomayim for almost forty years, retiring in 1940.

Mobile Jews maintained their own social institutions even as they assimilated to the local culture. The men of Sha’arai Shomayim founded the Fidelia Club in the 1880s. The group built a clubhouse on the corner of Government and Washington Streets, which became the site for many social events in the Mobile Jewish community as well as innumerable card games. Most of the Fidelia Club’s members were part of Mobile’s old German-Jewish families. The Fidelia Club closed in the early years of the Great Depression. In 1891, Mobile Jews also formed their own Mardi Gras Society called the Continental Mystic Crewe, which threw an annual masked ball in conjunction with the city’s Mardi Gras celebration. The group disbanded in 1913, although other Jewish Mardi Gras groups continued to hold lavish annual balls until 1922.

The Community Grows

In the late-nineteenth century, a growing number of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe began to settle in Mobile. By 1912, an estimated 1,400 Jews lived in Mobile. Many of the newcomers owned small retail stores along Dauphin and Government Streets in downtown Mobile, often living in apartments in the rear of the store. Others worked as traveling peddlers in the surrounding countryside. Used to stricter religious orthodoxy, many of the recent arrivals Jews did not care for the classical Reform Judaism of Sha’arai Shomayim, and sought to create a congregation of their own. By 1894, this group had founded the Orthodox Ahavas Chesed (Lovers of Mercy). At first, this congregation was relatively informal, with its male members gathering at different homes to pray together. For the High Holidays, they rented space from the German Relief Hall. For its first seven years, the congregation had no presidents or rabbis. In 1898, the members of Ahavas Chesed purchased twelve plots at Magnolia Cemetery.

The new congregation grew quickly. By 1907, it already had seventy members and a treasurer who used a horse and buggy to visit each member to collect their dues. The following year, Ahavas Chesed purchased a house at the corner of Conti and Warren Streets to use as a synagogue. At the dedication ceremony, the speakers included the mayor of Mobile, Pat Lyons, and Rabbi Moses of Sha’arai Shomayim. Reflecting the immigrant roots of its members, after the dedication ceremony, a religious service was held during which Ahavas Chesed’s spiritual leader, Rabbi Abraham Fram, addressed the congregation in Yiddish. With Mobile’s population of Eastern European Orthodox Jews ever increasing, Ahavas Chesed soon outgrew its first home, and quickly made plans to construct a new synagogue on the same site. On December 10, 1911, the members gathered to lay the cornerstone for the new building. The Jewish mayor of Mobile, Lazarus Schwarz, spoke at the ceremony. The synagogue was completed in record time, opening its doors on March 31, 1912.

Soon after, Ahavas Chesed hired its first ordained rabbi, Morris Lichtenstein, a graduate of the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York. In addition to leading services, Lichtenstein was responsible for slaughtering kosher meat for his congregants. Rabbi Lichtenstein only served Ahavas Chesed for four years, leaving in 1916. Although they had hired a JTS graduate, the congregation remained Orthodox, with separate seating for men and women and prayers exclusively in Hebrew. Sermons were often given in Yiddish since that was the language most members best understood. In 1914, Ahavas Chesed organized a heder religious school, which met every day after school in the basement of the synagogue. In keeping with Orthodox tradition, only boys received instruction at heder. However, some sisters were known to accompany their brothers to heder and learn Hebrew by ear while sitting in the back. By 1924, girls were allowed to participate in religious school.

In the late-nineteenth century, a growing number of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe began to settle in Mobile. By 1912, an estimated 1,400 Jews lived in Mobile. Many of the newcomers owned small retail stores along Dauphin and Government Streets in downtown Mobile, often living in apartments in the rear of the store. Others worked as traveling peddlers in the surrounding countryside. Used to stricter religious orthodoxy, many of the recent arrivals Jews did not care for the classical Reform Judaism of Sha’arai Shomayim, and sought to create a congregation of their own. By 1894, this group had founded the Orthodox Ahavas Chesed (Lovers of Mercy). At first, this congregation was relatively informal, with its male members gathering at different homes to pray together. For the High Holidays, they rented space from the German Relief Hall. For its first seven years, the congregation had no presidents or rabbis. In 1898, the members of Ahavas Chesed purchased twelve plots at Magnolia Cemetery.

The new congregation grew quickly. By 1907, it already had seventy members and a treasurer who used a horse and buggy to visit each member to collect their dues. The following year, Ahavas Chesed purchased a house at the corner of Conti and Warren Streets to use as a synagogue. At the dedication ceremony, the speakers included the mayor of Mobile, Pat Lyons, and Rabbi Moses of Sha’arai Shomayim. Reflecting the immigrant roots of its members, after the dedication ceremony, a religious service was held during which Ahavas Chesed’s spiritual leader, Rabbi Abraham Fram, addressed the congregation in Yiddish. With Mobile’s population of Eastern European Orthodox Jews ever increasing, Ahavas Chesed soon outgrew its first home, and quickly made plans to construct a new synagogue on the same site. On December 10, 1911, the members gathered to lay the cornerstone for the new building. The Jewish mayor of Mobile, Lazarus Schwarz, spoke at the ceremony. The synagogue was completed in record time, opening its doors on March 31, 1912.

Soon after, Ahavas Chesed hired its first ordained rabbi, Morris Lichtenstein, a graduate of the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York. In addition to leading services, Lichtenstein was responsible for slaughtering kosher meat for his congregants. Rabbi Lichtenstein only served Ahavas Chesed for four years, leaving in 1916. Although they had hired a JTS graduate, the congregation remained Orthodox, with separate seating for men and women and prayers exclusively in Hebrew. Sermons were often given in Yiddish since that was the language most members best understood. In 1914, Ahavas Chesed organized a heder religious school, which met every day after school in the basement of the synagogue. In keeping with Orthodox tradition, only boys received instruction at heder. However, some sisters were known to accompany their brothers to heder and learn Hebrew by ear while sitting in the back. By 1924, girls were allowed to participate in religious school.

As the Jewish boys waited for heder to open, they would play basketball at a nearby grammar school court. These informal games soon grew into the Hebrew Athletic Club, in which Mobile’s young Jews would compete in the city’s Sunday school basketball league against churches and YMCA teams. With a Star of David on their jerseys, Mobile’s Jewish youth held their own against other local teams. Efforts such as the Hebrew Athletic Club convinced many synagogue members of the need for a Jewish community center for social and athletic activities. In 1930, Ahavas Chesed purchased a three story brick building across the street from the synagogue. Named the Progressive Club, the building contained several meetings rooms, a recreation room, and an auditorium. In 1938, the building was demolished and replaced with a new structure that better met the needs of Mobile Jews, with a full gymnasium, auditorium, banquet hall, and kosher kitchen. Although Ahavas Chesed paid for the Progressive Club, it was open to all members of the Mobile Jewish community.

While Ahavas Chesed emerged as an active and thriving congregation, Sha’arai Shomayim continued to flourish as well. The congregation celebrated its fiftieth anniversary on October 21, 1894. Soon after, Sha’arai Shomayim enjoyed a period of sustained growth, going from ninety members in 1895 to 175 members in 1910. Due to this growth, the congregation began to discuss building a new, larger temple. On June 6th, 1906, they laid the cornerstone at their new site on Government Street. Alabama’s Lieutenant Governor, Russell Cunningham, was the keynote speaker. They dedicated their new temple a year later.

Charitable Efforts

As the oldest and largest Jewish congregation in Mobile, Sha’arai Shomayim was active in local charity efforts. In 1857, a group of women affiliated with the congregation founded the Ladies’ Hebrew Benevolent Society, helping to raise money for the fledgling congregation and various other causes. By 1907, the group had 100 members. The Ladies’ Sewing Society was founded in 1881 to supply clothing and linens to the Jewish Orphan’s Home in New Orleans. Leaders of Sha’arai Shomayim also worked with the Industrial Removal Office in New York to resettle poor Jewish immigrants in Mobile. They founded the United Hebrew Charities in 1904 to help with this effort. To help assimilate these newcomers, the group, led by Henry Hess, founded the Temple Institute, which offered English classes to these immigrants. In 1907, the school had thirty students. The congregation did not help only Jews; in 1895, when the St. Francis Street Methodist Church lost their building to a fire, they worshiped in the sanctuary of Sha’arai Shomayim.

While Ahavas Chesed emerged as an active and thriving congregation, Sha’arai Shomayim continued to flourish as well. The congregation celebrated its fiftieth anniversary on October 21, 1894. Soon after, Sha’arai Shomayim enjoyed a period of sustained growth, going from ninety members in 1895 to 175 members in 1910. Due to this growth, the congregation began to discuss building a new, larger temple. On June 6th, 1906, they laid the cornerstone at their new site on Government Street. Alabama’s Lieutenant Governor, Russell Cunningham, was the keynote speaker. They dedicated their new temple a year later.

Charitable Efforts

As the oldest and largest Jewish congregation in Mobile, Sha’arai Shomayim was active in local charity efforts. In 1857, a group of women affiliated with the congregation founded the Ladies’ Hebrew Benevolent Society, helping to raise money for the fledgling congregation and various other causes. By 1907, the group had 100 members. The Ladies’ Sewing Society was founded in 1881 to supply clothing and linens to the Jewish Orphan’s Home in New Orleans. Leaders of Sha’arai Shomayim also worked with the Industrial Removal Office in New York to resettle poor Jewish immigrants in Mobile. They founded the United Hebrew Charities in 1904 to help with this effort. To help assimilate these newcomers, the group, led by Henry Hess, founded the Temple Institute, which offered English classes to these immigrants. In 1907, the school had thirty students. The congregation did not help only Jews; in 1895, when the St. Francis Street Methodist Church lost their building to a fire, they worshiped in the sanctuary of Sha’arai Shomayim.

Mobile Jews Challenging Anti-Semitism

Jews enjoyed general acceptance in Mobile and were not hesitant to speak out against anti-Semitism. In the summer of 1910, when local defense attorney William C. Fitts reportedly made anti-Semitic remarks to the jury regarding the robbery of Julius W. Olensky’s pawn shop, the Jewish community published a letter of protest in the Mobile Register. The letter featured signatures from every segment of the local Jewish community, including Henry Hess, president of Sha’arai Shomayim, Isaac Schwartz, president of Ahavas Chesed, and seven other local Jewish leaders. Fitts, who had once served as Alabama’s Attorney General, denied making the remarks and threatened the Register with a libel suit, but the newspaper had the evidence of several witnesses to the trial and stood by its story. Fitts eventually admitted making the remark and apologized. Mobile Jews also challenged anti-Semitism in Europe. After the Nazis began to pass anti-Jewish laws in Germany, the local B’nai Brith sponsored a petition addressed to President Franklin Roosevelt calling on the U.S. government to do something to help alleviate the condition of Jews in Germany. Local Catholic and Protestant clergy also signed this petition.

Jewish Patriotism

In challenging anti-Semitism, both at home and abroad, Mobile Jews were exuding a confidence in their position in America. They embraced their citizenship, and expressed a strong patriotism for their country. Several served in the US military during the two World Wars, with some receiving special recognition for their sacrifice. After naval officer Esau Frohlichstein died fighting for the US in Mexico in 1914, a monument was erected in his memory with a plaque that read “A True American Patriot. Lover of Liberty, His Flag and Country.” Leon Schwarz, who later became mayor of Mobile, was an Alabama State Trooper before serving in the army during World War I. Mobile Jews who remained at home during the wars also did their part. During World War II, Mobile became a busy port, bringing an influx of soldiers into the area. The congregants of Ahavas Chesed and Sha’arai Shomayim went to great lengths to make Jewish servicemen feel at home. Over the holidays, Jewish servicemen were invited to the synagogues and homes of Mobile Jews.

Changes After World War II

After World War II, the Mobile Jewish community and its institutions entered a period of transition. Both Sha’arai Shomayim and Ahavas Chesed were located downtown, only one block away from each other, but by the 1940s, most of Mobile’s Jews were moving away from downtown to the more suburban western part of the city. Both congregations decided to follow their members. Ahavas Chesed had an option on a piece of property on Springhill Avenue, which they chose not to exercise. Sha’arai Shomayim, whose temple on Government Street was in need of extensive repairs, moved quickly to acquire the same property. They soon found a buyer for their old temple, and spent the next three years homeless, meeting at two local churches for services. The Sunday school met in the old Federal Building. Finally, in 1955, they dedicated the Springhill Avenue Temple, which became the popularly used name for the congregation. In 1960, Rabbi Irving Bloom, who had previously been a chaplain in the U.S. Air Force and an assistant rabbi at Temple Sinai in New Orleans, began serving Sha’arai Shomayim, guiding the congregation for the next thirteen years.

Jews enjoyed general acceptance in Mobile and were not hesitant to speak out against anti-Semitism. In the summer of 1910, when local defense attorney William C. Fitts reportedly made anti-Semitic remarks to the jury regarding the robbery of Julius W. Olensky’s pawn shop, the Jewish community published a letter of protest in the Mobile Register. The letter featured signatures from every segment of the local Jewish community, including Henry Hess, president of Sha’arai Shomayim, Isaac Schwartz, president of Ahavas Chesed, and seven other local Jewish leaders. Fitts, who had once served as Alabama’s Attorney General, denied making the remarks and threatened the Register with a libel suit, but the newspaper had the evidence of several witnesses to the trial and stood by its story. Fitts eventually admitted making the remark and apologized. Mobile Jews also challenged anti-Semitism in Europe. After the Nazis began to pass anti-Jewish laws in Germany, the local B’nai Brith sponsored a petition addressed to President Franklin Roosevelt calling on the U.S. government to do something to help alleviate the condition of Jews in Germany. Local Catholic and Protestant clergy also signed this petition.

Jewish Patriotism

In challenging anti-Semitism, both at home and abroad, Mobile Jews were exuding a confidence in their position in America. They embraced their citizenship, and expressed a strong patriotism for their country. Several served in the US military during the two World Wars, with some receiving special recognition for their sacrifice. After naval officer Esau Frohlichstein died fighting for the US in Mexico in 1914, a monument was erected in his memory with a plaque that read “A True American Patriot. Lover of Liberty, His Flag and Country.” Leon Schwarz, who later became mayor of Mobile, was an Alabama State Trooper before serving in the army during World War I. Mobile Jews who remained at home during the wars also did their part. During World War II, Mobile became a busy port, bringing an influx of soldiers into the area. The congregants of Ahavas Chesed and Sha’arai Shomayim went to great lengths to make Jewish servicemen feel at home. Over the holidays, Jewish servicemen were invited to the synagogues and homes of Mobile Jews.

Changes After World War II

After World War II, the Mobile Jewish community and its institutions entered a period of transition. Both Sha’arai Shomayim and Ahavas Chesed were located downtown, only one block away from each other, but by the 1940s, most of Mobile’s Jews were moving away from downtown to the more suburban western part of the city. Both congregations decided to follow their members. Ahavas Chesed had an option on a piece of property on Springhill Avenue, which they chose not to exercise. Sha’arai Shomayim, whose temple on Government Street was in need of extensive repairs, moved quickly to acquire the same property. They soon found a buyer for their old temple, and spent the next three years homeless, meeting at two local churches for services. The Sunday school met in the old Federal Building. Finally, in 1955, they dedicated the Springhill Avenue Temple, which became the popularly used name for the congregation. In 1960, Rabbi Irving Bloom, who had previously been a chaplain in the U.S. Air Force and an assistant rabbi at Temple Sinai in New Orleans, began serving Sha’arai Shomayim, guiding the congregation for the next thirteen years.

The post-war period saw changes for Ahavas Chesed as well. They had long been slowly moving away from Orthodoxy, and in 1952, after much internal debate, the congregation decided to affiliate with the Conservative movement. This brought several changes, including the hiring of their first Conservative rabbi, Manuel Greenstein, who helped the congregation make the transition. Rabbi Greenstein helped increase synagogue participation by introducing a Men’s Club and a youth group affiliated with the United Synagogue Youth. In 1954 the Ladies Aid Society became affiliated with the National Women’s League of the United Synagogue of America, and changed its name to the Ahavas Chesed Sisterhood. Joining the Conservative movement opened the door to further ritual changes in 1980, including counting women toward the minyan and allowing women to be called to the bimah for an Aliyah.

Ahavas Chesed soon followed Sha’arai Shomayim westward, building a new synagogue on the corner of Dauphin and Hannon Streets in 1956. The new building held classrooms, an auditorium, a kosher kitchen, a chapel, as well as a main sanctuary that had 264 seats. Rabbi Harold Friedman, who had earlier been a bus-driving circuit riding rabbi in North Carolina, took over the pulpit at Ahavas Chesed in 1958, and focused on bolstering the congregation’s religious school. The congregation thrived under Rabbi Friedman’s leadership, and soon began to outgrow its facility; its religious school rooms were designed to hold 100 students, but by 1959 they had 133 children enrolled.

Ahavas Chesed soon followed Sha’arai Shomayim westward, building a new synagogue on the corner of Dauphin and Hannon Streets in 1956. The new building held classrooms, an auditorium, a kosher kitchen, a chapel, as well as a main sanctuary that had 264 seats. Rabbi Harold Friedman, who had earlier been a bus-driving circuit riding rabbi in North Carolina, took over the pulpit at Ahavas Chesed in 1958, and focused on bolstering the congregation’s religious school. The congregation thrived under Rabbi Friedman’s leadership, and soon began to outgrow its facility; its religious school rooms were designed to hold 100 students, but by 1959 they had 133 children enrolled.

The Jewish Progressive Club soon followed Ahavas Chesed, moving west to a property on Airport Boulevard. Reflecting the suburbanization of its membership, the new site had a golf course and clubhouse, which prompted the leadership to change its name to the Highland Country Club. Since the Mobile Jewish community was not large enough to support a country club on its own, the golf course was sold in the early 1970s, and the remaining building became a Jewish Community Center. The Mobile JCC was finally sold in 1991 due to a lack of use by the Jewish community, and the proceeds were split between the two congregations.

By 1989 Ahavas Chesed had finally gotten too big for their building and plans were made to construct a new synagogue. On February 11, 1990, the new synagogue was dedicated on Regents Way. The design of the main sanctuary consists of two circular columns on each side of the bimah along with six wooden panels between them, making the wall look like a Torah opened in study.

Mayer “Bubba” Mitchell

Though by national standards the Mobile Jewish community has always been quite small, it has produced important leaders of the American Jewish community. Most notable among these was Mayer “Bubba” Mitchell. Born in New Orleans in 1933 and raised in Mobile, Mitchell became a successful real estate developer with projects throughout the southeast. After selling his business in 1986, Mitchell focused much of his attention on philanthropy, giving over $36 million to the University of South Alabama, He also supported Jewish causes, such as his congregation Ahavas Chesed, Camp Ramah Darom, and the Jewish Theological Seminary. Mitchell became especially active with the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), serving as both its president and board chairman. He was closely involved in politics, and amassed a great deal of influence in Washington before his death in 2007.

Interfaith Activities

Mobile’s Jews have long been committed to interfaith dialogue and alliances. In 1961 the Men’s Club of Sha’arai Shomayim sponsored what would become an annual Ministerial Institute for seventy local protestant ministers. Prominent scholars attended these meetings and discussed the relationship between Christian and Jewish thought. In November of 1968, the congregation held an interfaith Thanksgiving service with the St. Francis Street Methodist Church, the same church that had used the temple’s sanctuary when their building was lost in a fire in 1895. The Jewish and Christian communities came together on September 6, 1972, to mourn the victims of the terrorist attack on Israeli competitors in the Munich Olympics. More than 400 people gathered to express their support and grief inside the Springhill Avenue Temple that night.

An Anti-Semitic Incident

Despite close Christian-Jewish relations, the Jews of Mobile suffered an unexpected trauma on November 11, 1988, when the Springhill Avenue Temple and the Ahavas Chesed synagogue were both vandalized. They were painted with anti-Jewish slogans, swatstikas and obscenities. The vandalism occurred three nights after the 50th anniversary of Kristallnacht. The Mobile Police Department took quick action and arrested the perpetrators.

By 1989 Ahavas Chesed had finally gotten too big for their building and plans were made to construct a new synagogue. On February 11, 1990, the new synagogue was dedicated on Regents Way. The design of the main sanctuary consists of two circular columns on each side of the bimah along with six wooden panels between them, making the wall look like a Torah opened in study.

Mayer “Bubba” Mitchell

Though by national standards the Mobile Jewish community has always been quite small, it has produced important leaders of the American Jewish community. Most notable among these was Mayer “Bubba” Mitchell. Born in New Orleans in 1933 and raised in Mobile, Mitchell became a successful real estate developer with projects throughout the southeast. After selling his business in 1986, Mitchell focused much of his attention on philanthropy, giving over $36 million to the University of South Alabama, He also supported Jewish causes, such as his congregation Ahavas Chesed, Camp Ramah Darom, and the Jewish Theological Seminary. Mitchell became especially active with the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), serving as both its president and board chairman. He was closely involved in politics, and amassed a great deal of influence in Washington before his death in 2007.

Interfaith Activities

Mobile’s Jews have long been committed to interfaith dialogue and alliances. In 1961 the Men’s Club of Sha’arai Shomayim sponsored what would become an annual Ministerial Institute for seventy local protestant ministers. Prominent scholars attended these meetings and discussed the relationship between Christian and Jewish thought. In November of 1968, the congregation held an interfaith Thanksgiving service with the St. Francis Street Methodist Church, the same church that had used the temple’s sanctuary when their building was lost in a fire in 1895. The Jewish and Christian communities came together on September 6, 1972, to mourn the victims of the terrorist attack on Israeli competitors in the Munich Olympics. More than 400 people gathered to express their support and grief inside the Springhill Avenue Temple that night.

An Anti-Semitic Incident

Despite close Christian-Jewish relations, the Jews of Mobile suffered an unexpected trauma on November 11, 1988, when the Springhill Avenue Temple and the Ahavas Chesed synagogue were both vandalized. They were painted with anti-Jewish slogans, swatstikas and obscenities. The vandalism occurred three nights after the 50th anniversary of Kristallnacht. The Mobile Police Department took quick action and arrested the perpetrators.

The Jewish Community in Mobile Today

Today, both the Springhill Avenue Temple and Ahavas Chesed continue to thrive. In 2008, the Springhill Temple served 250 families with 100 students participating in its religious school. Ahavas Chesed had 174 member families with thirty students in its religious school in 2008.

The Jewish population of Mobile peaked at an estimated 2,200 Jews in 1918, just after the height of the Eastern European immigration. During the middle decades of the twentieth century, the city’s Jewish population gradually declined. By the 1960s, it had reached a plateau of around 1,200 people, where it remains today.

Unlike many other Southern communities, Mobile has maintained a significant Jewish population, as the city has continued to thrive economically. With several strong community institutions, including its two synagogues and the Mobile Jewish Welfare Fund, the Mobile Jewish community is continuing the legacy created by its early pioneers. What started as a history of individuals before 1841 became a history of collaboration and unity in the years since.

The Jewish population of Mobile peaked at an estimated 2,200 Jews in 1918, just after the height of the Eastern European immigration. During the middle decades of the twentieth century, the city’s Jewish population gradually declined. By the 1960s, it had reached a plateau of around 1,200 people, where it remains today.

Unlike many other Southern communities, Mobile has maintained a significant Jewish population, as the city has continued to thrive economically. With several strong community institutions, including its two synagogues and the Mobile Jewish Welfare Fund, the Mobile Jewish community is continuing the legacy created by its early pioneers. What started as a history of individuals before 1841 became a history of collaboration and unity in the years since.