Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities

Overview >> Mississippi >> Meridian

Overview

|

Meridian, the seat of Lauderdale County, is the historical transportation and industrial hub of eastern Mississippi. The city was founded not long after the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek ceded the remainder of the Choctaw Nation’s Mississippi territory to the United States in 1830. While the area around Meridian experienced significant population growth from 1840 to 1860, Lauderdale County and Meridian developed at an even faster pace in the late 19th century. From then until the mid-20th century, Meridian boasted a more industrialized economy than most other Mississippi cities and attracted a higher percentage of immigrants than any area of Mississippi except the Gulf Coast.

Jewish settlers arrived in the vicinity of Meridian by 1837. Several families settled in the nearby town of Marion, which was then the county seat. When Meridian emerged as the center of local economic life after the Civil War, it also became the center of Jewish life. Jewish owned businesses played key roles in the development of the city. As of the early 21st century, Meridian’s Jewish population has declined significantly, but formerly Jewish-owned buildings still define the city’s downtown. |

Early Jewish Settlers and Prominent Merchant Families

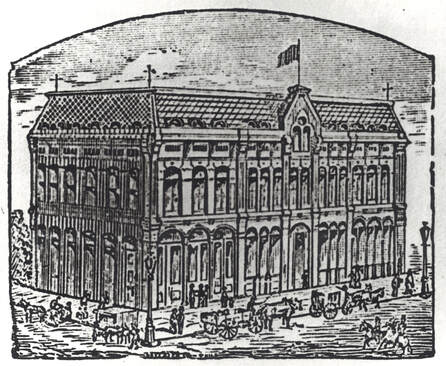

Joseph Baum & Co.

Joseph Baum & Co.

Recorded Jewish life in Lauderdale County began in the town of Marion, located just six miles from the center of present-day Meridian. County records show that David Rosenbaum purchased land in the town in 1837. The families of Abraham Threefoot, Isaac Rosenbaum, Leopold Rosenbaum, E. Lowenstein, and Jacob Cohen reportedly lived in Marion during these early years. These earliest Jewish residents came primarily from Central Europe, and census records indicate that the Rosenbaum and Lowenstein families immigrated from Bohemia.

The presence of enslaved women in Jewish homes in Lauderdale County demonstrates that at least some of these pre-Civil War settlers experienced relative financial success. The 1860 Slave Schedules of the United States Federal Census name David Rosenbaum and a J. Lowenstein as enslavers, with one Black woman listed for each individual. These women probably performed domestic work for the families. A five-year-old girl also appears as property of J. Lowenstein. The Rosenbaum and Lowenstein families’ participation in the system of enslavement was not unusual for Jews in the South at that time, whose views on slavery differed little from those of other white southerners.

After the Civil War wreaked havoc on east Mississippi, Meridian became the hub of Lauderdale County. By the time Meridian became the county seat in 1870, ten Jewish families lived in the growing town. Within twenty years, six railroads met in Meridian, and the population increased from 4,000 residents in 1880 to more than 23,000 in 1910. Throughout this era of explosive growth, Jewish merchants proved central to the commercial life of the city.

Joseph Baum, an immigrant from Boosen, Prussia, established a large business in Meridian during the 1870s. At age 25, he operated a wholesale and retail dry goods store which also purchased cotton from local farmers. The business eventually encompassed an entire block of Front Street, known as the “Baum Block.” In 1892, A.J. Lyon and Company joined the “Baum Block.” Lyon, with his brothers-in-law Ike and Mike Rosenbaum, became known as east Mississippi’s number one wholesale grocer, a title which the business held for 50 years.

The presence of enslaved women in Jewish homes in Lauderdale County demonstrates that at least some of these pre-Civil War settlers experienced relative financial success. The 1860 Slave Schedules of the United States Federal Census name David Rosenbaum and a J. Lowenstein as enslavers, with one Black woman listed for each individual. These women probably performed domestic work for the families. A five-year-old girl also appears as property of J. Lowenstein. The Rosenbaum and Lowenstein families’ participation in the system of enslavement was not unusual for Jews in the South at that time, whose views on slavery differed little from those of other white southerners.

After the Civil War wreaked havoc on east Mississippi, Meridian became the hub of Lauderdale County. By the time Meridian became the county seat in 1870, ten Jewish families lived in the growing town. Within twenty years, six railroads met in Meridian, and the population increased from 4,000 residents in 1880 to more than 23,000 in 1910. Throughout this era of explosive growth, Jewish merchants proved central to the commercial life of the city.

Joseph Baum, an immigrant from Boosen, Prussia, established a large business in Meridian during the 1870s. At age 25, he operated a wholesale and retail dry goods store which also purchased cotton from local farmers. The business eventually encompassed an entire block of Front Street, known as the “Baum Block.” In 1892, A.J. Lyon and Company joined the “Baum Block.” Lyon, with his brothers-in-law Ike and Mike Rosenbaum, became known as east Mississippi’s number one wholesale grocer, a title which the business held for 50 years.

|

Hotel Lamar was opened in 1927 by Sam and Joe Meyer. The Meyer family moved from Kosciusko, Mississippi, to Meridian in the 1860s, when Joe and Sam were children. Their father, Jacob, was a business partner of Marks Winner, another early Jewish merchant in Meridian, and Joe and Sam worked there with their brother Mattimore until his death led to the dissolution of the firm in 1903. At that point, Joe and Sam founded Meyer Brothers, a grocery wholesale and farm supply business that they ran until 1927. At 11 stories tall, the 200-room Hotel Lamar was the tallest building in the city when it was completed.

|

The Marks-Rothenberg family developed another successful Front Street business in the late-19th century. Israel A. Marks, a German-born immigrant, began his career as a peddler supplying rural families with dry goods. In the 1870s he operated a wholesale dry goods business in Meridian and in the 1880s consolidated his business with Lichtenstein and Company; the combined operation occupied nearly a full block of Front Street. After Lichtenstein’s departure in 1887, Marks began a company with his three half-brothers: Sam, Levi, and Marks Rothenberg. The new firm, Marks, Rothenberg & Company, became one of the largest wholesale grocery and dry goods businesses in the South. In 1899, they opened a mammoth five-story location. All four partners of Marks, Rothenberg & Company became leading citizens in Meridian. Levi Rothenberg was the president of Meridian’s first bank, and Israel Marks served on the board of another local bank. Levi was also an early member of the fire brigade and served on the water works and insurance commissions.

Israel Marks and his brothers, along with members of the Threefoot family, also played an instrumental role in establishing Highland Park, a European-style “pleasure park” which served as a streetcar terminus and opened at the western edge of town in 1909. Marks served as president of the park commission from its formation until his death in 1914, and a statue of Marks was erected there in 1913. The proprietors of Marks, Rothenberg & Company are perhaps best known for building the Grand Opera House next to their downtown store. Completed in 1890, the opera house attracted performers from all over the United States. After lying dormant for almost 80 years, the opera house was restored in 2006 and reopened as the Mississippi State University Riley Center.

Israel Marks and his brothers, along with members of the Threefoot family, also played an instrumental role in establishing Highland Park, a European-style “pleasure park” which served as a streetcar terminus and opened at the western edge of town in 1909. Marks served as president of the park commission from its formation until his death in 1914, and a statue of Marks was erected there in 1913. The proprietors of Marks, Rothenberg & Company are perhaps best known for building the Grand Opera House next to their downtown store. Completed in 1890, the opera house attracted performers from all over the United States. After lying dormant for almost 80 years, the opera house was restored in 2006 and reopened as the Mississippi State University Riley Center.

Organized Jewish Life

By the time that Meridian entered its late-19th-century heyday, area Jews had prayed together for years. Jewish residents in Marion and Meridian originally met together, and once hoped to construct a synagogue between the two towns. When Meridian emerged as the dominant commercial hub following the Civil War, Marion Jews simply moved to Meridian, and the plan never came to fruition.

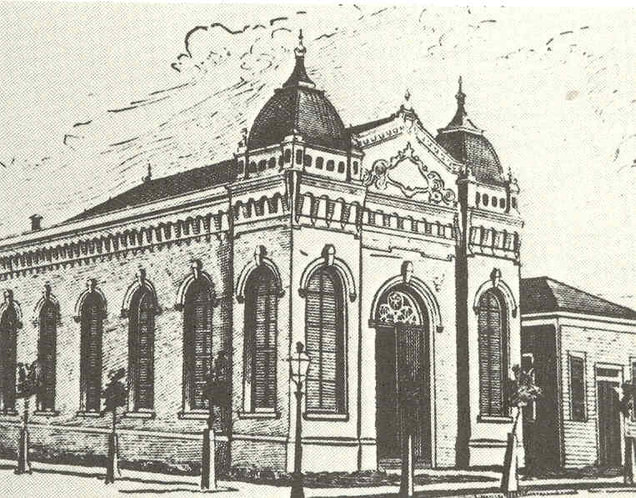

The original Beth Israel synagogue.

The original Beth Israel synagogue.

Meridian became home to Lauderdale county’s first Jewish congregation, Beth Israel, in 1868. David Rosenbaum, Alex Lowenstein, Abraham Threefoot, and G.H. Lesser served as founding officers. Under their leadership, Beth Israel immediately acquired land for a cemetery, which they purchased for $100. The fledgling congregation met in several temporary locations in its early years, including a school house on 24th Avenue and Ninth Street, a room up above Carney’s Grocery Store, and Sheehan Hall. By 1873, they had hired Rabbi David Burgheim as their spiritual leader. Initially, only ten families belonged to the congregation, but Beth Israel grew quickly along with Meridian itself.

From its earliest days, Beth Israel adopted Reform Judaism, and the congregation joined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations in 1874. By 1878 Congregation Beth Israel had grown to 50 members, who decided to construct a permanent house of worship. Their brick synagogue, located on 22nd Avenue, was the first building in the city with gas-powered lighting. Rabbi Burgheim was succeeded by Rabbi W. Weinstein, Rabbi Jacobs, and Rabbi Judah Wechsler. None of these early rabbis stayed in Meridian for very long. Beth Israel’s religious school enrollment reached 32 children in the late 1870s, which reflected a significant population of young families at the time.

Among the early rabbis of Beth Israel, Judah Wechsler stands out for his civic pursuits, which paralleled the increasingly visible public profiles of his congregants. Wechsler, who became Beth Israel’s spiritual leader in 1887, was heavily involved in the issue of African American education. In 1888, he campaigned for a bond issue to construct the first publicly-funded, brick school building for African Americans in Mississippi. When the bond issue passed, Meridian’s Black community asked that the new school be named in the rabbi’s honor. The Wechsler School, completed in 1894, served as an important institution in the local Black community for decades. Although the school briefly fell into disuse in the 1980s, community groups secured funding to begin rehabilitating the school in the early 21st century.

From its earliest days, Beth Israel adopted Reform Judaism, and the congregation joined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations in 1874. By 1878 Congregation Beth Israel had grown to 50 members, who decided to construct a permanent house of worship. Their brick synagogue, located on 22nd Avenue, was the first building in the city with gas-powered lighting. Rabbi Burgheim was succeeded by Rabbi W. Weinstein, Rabbi Jacobs, and Rabbi Judah Wechsler. None of these early rabbis stayed in Meridian for very long. Beth Israel’s religious school enrollment reached 32 children in the late 1870s, which reflected a significant population of young families at the time.

Among the early rabbis of Beth Israel, Judah Wechsler stands out for his civic pursuits, which paralleled the increasingly visible public profiles of his congregants. Wechsler, who became Beth Israel’s spiritual leader in 1887, was heavily involved in the issue of African American education. In 1888, he campaigned for a bond issue to construct the first publicly-funded, brick school building for African Americans in Mississippi. When the bond issue passed, Meridian’s Black community asked that the new school be named in the rabbi’s honor. The Wechsler School, completed in 1894, served as an important institution in the local Black community for decades. Although the school briefly fell into disuse in the 1980s, community groups secured funding to begin rehabilitating the school in the early 21st century.

The Early 20th Century

Meridian’s rapid development in the late 19th century not only established its most successful Jewish merchants as highly visible civic leaders, it also attracted new Jewish residents to the city, including eastern European immigrants. The established Jewish community assisted Jewish newcomers in obtaining jobs and housing, and Beth Israel offered night classes to encourage their acculturation into American society. Despite apparently cordial relations, a number of recent arrivals were unsatisfied with the congregation’s Reform practices, and in 1895 they founded a second, Orthodox congregation, Ohel Jacob.

The small congregation worshiped in the Pythian Hall and the Odd Fellows Hall in its early years, and also met in the home of member Louis Davidson. In 1907, Ohel Jacob had 22 members, and only received $150 in annual dues income, a far cry from the $4500 a year Beth Israel received from its members. While Meridian’s Orthodox Jews maintained traditional practices when possible, they also had to adjust to the social and economic realities of their new home. In 1907, for example, Ohel Jacob held Saturday morning services from 6 to 8 am, so that members could fulfill their religious duties early and then open their stores for the busiest day of the week.

The small congregation worshiped in the Pythian Hall and the Odd Fellows Hall in its early years, and also met in the home of member Louis Davidson. In 1907, Ohel Jacob had 22 members, and only received $150 in annual dues income, a far cry from the $4500 a year Beth Israel received from its members. While Meridian’s Orthodox Jews maintained traditional practices when possible, they also had to adjust to the social and economic realities of their new home. In 1907, for example, Ohel Jacob held Saturday morning services from 6 to 8 am, so that members could fulfill their religious duties early and then open their stores for the busiest day of the week.

While Orthodox Jewish immigrants established Ohel Jacob, the Reform community continued to grow. Under the leadership of Rabbi Max Raisin, Beth Israel boasted more than 80 member families in the first decade of the 20th century, and its religious school enrolled nearly fifty students. The congregation built a new synagogue at the corner of 11th Street and 24th Avenue in 1906. Designed by architect P.J. Krause, the new building was modeled after the Temple of Athena Nike, one of the major temples of the Acropolis. Fourteen marble steps led to the main entrance, which featured a row of large ionic columns. The synagogue interior, which could seat 500 worshippers, also mimicked the octagonal shape of early Grecian architecture. Interior ornamentation included a large green glass dome, a grand pipe organ, and stained glass windows. After the new building suffered a fire in its first year, the congregation held services at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church. Beth Israel later returned the favor when the Episcopal congregation renovated its own building.

As Meridian’s Jewish population grew, so did the Jewish community’s importance in regional Jewish life. In 1907 Beth Israel hosted a conference for Jewish religious school teachers, featuring distinguished out-of-town presenters. The approximately forty visiting educators stayed in the homes of local Jewish families. In addition, Congregation Beth Israel offered religious services throughout the conference and advertised in the Meridian Evening Star that these services were open to the public.

As Meridian’s Jewish population grew, so did the Jewish community’s importance in regional Jewish life. In 1907 Beth Israel hosted a conference for Jewish religious school teachers, featuring distinguished out-of-town presenters. The approximately forty visiting educators stayed in the homes of local Jewish families. In addition, Congregation Beth Israel offered religious services throughout the conference and advertised in the Meridian Evening Star that these services were open to the public.

Meridian emerged as the largest city in the state by 1910 and held the title into the 1920s. By 1927 the Meridian Jewish population numbered 575 individuals, and the community remained prominent in civic life. Rabbi William Ackerman moved to town in 1924 and was named the city’s “Most Worthful Citizen” by the Kiwanis Club in 1926. In 1929 Ohel Jacob built its own (more modest) house of worship at 1300 25th Avenue. The Orthodox congregation also acquired a small cemetery across from the Beth Israel cemetery. While local Jews enjoyed a great deal of acceptance in white, Christian society, they also maintained their own social institutions in the early 20th century. Until the early 1930s, affluent Jews of Meridian belonged to the Standard Club, which occupied a large building with meeting rooms and a grand ballroom. In the business world, Harold Meyer, Sr., and Hunter Webb (who was not Jewish) opened Meywebb Hosiery Mills in 1930, and their partnership across religious lines further demonstrated the integration of Meridian Jews into the economic life of the city.

When the Great Depression disrupted economic life in Meridian beginning in 1929, Jewish businesses suffered as well, but they also helped the town to endure the downturn. Grocery wholesaler Ike Rosenbaum continued to sell on credit to struggling grocers as long as they had been fair and honest in their dealings. According to Ike’s son I. A. Rosenbaum, J.D. Clark & Son was one such business. When Clark heard his Presbyterian minister declare that Jews would not go to heaven, he got up and walked out of the sanctuary, saying, “if Ike Rosenbaum can’t go, I don’t want to go.”

When the Great Depression disrupted economic life in Meridian beginning in 1929, Jewish businesses suffered as well, but they also helped the town to endure the downturn. Grocery wholesaler Ike Rosenbaum continued to sell on credit to struggling grocers as long as they had been fair and honest in their dealings. According to Ike’s son I. A. Rosenbaum, J.D. Clark & Son was one such business. When Clark heard his Presbyterian minister declare that Jews would not go to heaven, he got up and walked out of the sanctuary, saying, “if Ike Rosenbaum can’t go, I don’t want to go.”

The Post-War Era

Meridian grew steadily during the 1930s and 1940s, and Jewish life remained stable into the mid-20th century. Beth Israel enjoyed the leadership of Rabbi William Ackerman, the longest-serving clergy person in the congregation’s history, until his unexpected death in 1950. Rather than immediately seeking to hire an ordained rabbi, the congregation requested that his widow, Paula Ackerman, serve as their “spiritual leader” until the congregation could find a suitable rabbinical candidate. Mrs. Ackerman, who had become an indispensable community leader herself, filled the role for nearly three years. Although she had not received formal religious training, she successfully led services, gave sermons, and conducted marriages and funerals during her tenure. In doing so, Mrs. Ackerman became the first woman to lead a mainstream American Jewish congregation, twenty years before the Reform movement began ordaining women rabbis. The decision to retain Mrs. Ackerman drew widespread attention, ranging from curiosity to indignation, but the congregation did not waver in their support for her. In 1962 Mrs. Ackerman served briefly as the leader of her childhood congregation in Pensacola, Florida, when they found themselves in need of a spiritual leader.

By the 1960s Beth Israel synagogue required extensive repairs, and the congregation opted to construct a new building in a suburban neighborhood rather than renovate the downtown temple that had been built in 1906. They purchased a rustic five-acre plot in the Broadmoor subdivision. The new facility, dedicated in December 1964, was composed of three buildings, all designed by architect Chris Risher, Sr.: a sanctuary that could hold 200 people, a social hall with a kitchen and library, and an education building. The Congregation also added a Holocaust Memorial that was commissioned by three local Christians. The memorial stone is shaped like the Ten Commandments and depicts Cain killing Abel; it was designed by Beth Israel congregant Helen P. Shapiro, an artist and native of Meridian.

While the Holocaust memorial attested to a long history of amicable relationships between Meridian Jews and the white Christian community, the rise of Black civil rights activism in the 1950s and 1960s threatened to disrupt that spirit of interfaith cooperation. Meridian Jews, like co-religionists elsewhere in the South, reacted ambivalently to the movement. Michael and Rita Schwerner, two Jews from New York, came to Meridian in 1964 to organize a voting rights campaign as part of the Mississippi Summer Project (commonly known as Freedom Summer). They received a cool reception from the Meridian Jewish community, some of whom opposed the movement and some of whom feared being associated with such “outside agitators.” Several local Jews, including Rabbi Milton Schlager, found time to meet with the Schwerners. Although the locals expressed sympathy for the Civil Rights cause, they questioned the young activists’ tactics.

While the Holocaust memorial attested to a long history of amicable relationships between Meridian Jews and the white Christian community, the rise of Black civil rights activism in the 1950s and 1960s threatened to disrupt that spirit of interfaith cooperation. Meridian Jews, like co-religionists elsewhere in the South, reacted ambivalently to the movement. Michael and Rita Schwerner, two Jews from New York, came to Meridian in 1964 to organize a voting rights campaign as part of the Mississippi Summer Project (commonly known as Freedom Summer). They received a cool reception from the Meridian Jewish community, some of whom opposed the movement and some of whom feared being associated with such “outside agitators.” Several local Jews, including Rabbi Milton Schlager, found time to meet with the Schwerners. Although the locals expressed sympathy for the Civil Rights cause, they questioned the young activists’ tactics.

When Ku Klux Klan members abducted and murdered Michael Schwerner—along with fellow Jewish northerner Andrew Goodman and local Black activist James Chaney—it confirmed the potential dangers posed by Jewish involvement in the movement. Although Rabbi Schlager and other local Jews had not been especially visible as proponents of Black Civil Rights, increasing violence made it more difficult to stay silent. After the Klan targeted local Black churches with bombings and burnings in 1968, several Meridian Jews became involved in the Committee of Conscience, which advocated for investigations and prosecutions of the culprits. Violent segregationists developed a strong following in Meridian, and Jewish school board member Lucille Rosenbaum received death threats after the local school board finally agreed to desegregate in the late 1960s.

The most intense period of anti-Jewish violence occured in 1968. Shortly after midnight on May 28th, a charge of dynamite exploded at the Beth Israel education building. The blast damaged classroom walls, caused a partial collapse of the roof, and shattered windows in two neighboring homes. It was the seventh Klan attack at a Meridian-area place of worship to take place since the fall, and it followed two bombings (perpetrated by the same group) that targeted Jackson Jews in September 1967. Members of the Meridian and Jackson Jewish communities helped raise money to pay off Klan informants, and the FBI uncovered a list of potential targets that included Meyer Davidson, a prominent Jewish resident of Meridian. Early in the morning of June 30th, local police and FBI agents staged a stakeout at Davidson’s house. (The family had been relocated for safety.) When Thomas Tarrants, a white nationalist terrorist, approached the home with a load of dynamite, the law enforcement officers intervened. A shootout and a car chase ensued, and Tarrants and two other individuals were seriously wounded. Police gunfire killed Tarrants’ accomplice, an elementary school teacher from Jackson.

The most intense period of anti-Jewish violence occured in 1968. Shortly after midnight on May 28th, a charge of dynamite exploded at the Beth Israel education building. The blast damaged classroom walls, caused a partial collapse of the roof, and shattered windows in two neighboring homes. It was the seventh Klan attack at a Meridian-area place of worship to take place since the fall, and it followed two bombings (perpetrated by the same group) that targeted Jackson Jews in September 1967. Members of the Meridian and Jackson Jewish communities helped raise money to pay off Klan informants, and the FBI uncovered a list of potential targets that included Meyer Davidson, a prominent Jewish resident of Meridian. Early in the morning of June 30th, local police and FBI agents staged a stakeout at Davidson’s house. (The family had been relocated for safety.) When Thomas Tarrants, a white nationalist terrorist, approached the home with a load of dynamite, the law enforcement officers intervened. A shootout and a car chase ensued, and Tarrants and two other individuals were seriously wounded. Police gunfire killed Tarrants’ accomplice, an elementary school teacher from Jackson.

As the most heated years of the civil rights struggle passed, Meridian Jews sought to put the turbulence of the mid-to-late 1960s behind them. In later decades, Beth Israel members pointed out that the bombers had driven in from Jackson and were not locals. Jewish families also continued to play prominent roles in the city’s civic and economic life. I.A. Rosenbaum (Lucille’s husband) served eight years as mayor in the 1970s and 1980s, and his Jewishness never became a public issue.

A Shrinking Jewish Community

I. A. Rosenblum c. 1990. Photo by Bill Aron.

I. A. Rosenblum c. 1990. Photo by Bill Aron.

When Beth Israel built its new synagogue in 1964, the city’s most prosperous years were already behind it. Jewish wholesale and retail businesses became less profitable over subsequent decades, and the Jewish population declined as younger people sought out educational and professional opportunities in other cities. Ohel Jacob, never a large congregation, closed in the early 1990s. For decades (and largely under the leadership of Sammie Davidson) it had operated solely as a meeting place for semiweekly afternoon prayer services and high holiday observances, and its members also belonged to Beth Israel. The larger Reform congregation continued to employ full-time rabbis throughout the 20th century, but has relied primarily on part-time rabbis from other cities since 2005. At that time the Reform congregation’s membership had fallen to 40 individuals, most of whom were older adults, and there were no longer sufficient numbers of Jewish youth to support a religious school or youth group.

In 2010 the congregation, like some other small-town Jewish communities, announced the creation of a grant program to attract new Jewish families, but the initiative did not spur new growth. In 2019 Congregation Beth Israel celebrated its 150th anniversary. The Meridan Star published a series of reminiscences from members of longstanding families, relative newcomers, and Meridian natives who had moved elsewhere. They remarked on the close bonds shared by the small community and the tenacity required to sustain Jewish life in a place that some people would expect to have no Jewish population at all.

In 2010 the congregation, like some other small-town Jewish communities, announced the creation of a grant program to attract new Jewish families, but the initiative did not spur new growth. In 2019 Congregation Beth Israel celebrated its 150th anniversary. The Meridan Star published a series of reminiscences from members of longstanding families, relative newcomers, and Meridian natives who had moved elsewhere. They remarked on the close bonds shared by the small community and the tenacity required to sustain Jewish life in a place that some people would expect to have no Jewish population at all.

Selected Bibliography

Jack Nelson, Terror in the Night: The Klan's Campaign Against the Jews (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1993).

Leo E. and Evelyn Turitz, Jews in Early Mississippi (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 1983).

Jack Nelson, Terror in the Night: The Klan's Campaign Against the Jews (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1993).

Leo E. and Evelyn Turitz, Jews in Early Mississippi (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 1983).