Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Jackson, Mississippi

Overview >> Mississippi >> Jackson

Historical Overview

|

Jackson, located in central Mississippi, sits at the junction of the Pearl River and the Natchez Trace, a trade route that predates the arrival of European colonists by thousands of years. In the 1700s, the French-Canadian trader Louis Lefleur established a trading post in present-day Jackson. The site, known as Lefleur’s Bluff, remained part of Choctaw territory until 1820, when a treaty opened the area to Euro-American settlement. Shortly thereafter, Mississippi’s state legislature established a new state capitol nearby and renamed the town after Andrew Jackson, the future president. The capital city served as a steamboat port and then a railroad center and—despite its destruction during the Civil War—grew into a hub for education, medicine, commerce, and state government.

Jackson attracted Jewish settlers from Germany and Alsace-Lorraine in the 1850s and from Poland in the 1870s and 1880s, many of whom established themselves as merchants. The Jewish population of Jackson became the state’s largest in the mid-20th century and remains so in the early 21st century. The city’s only synagogue, Beth Israel Congregation, has served Jackson Jews since 1860, and its membership is approximately 170 households as of 2021. The local Jewish population has declined since peaking in approximately 2010, as out-migrations and mortality have outpaced the arrival of new Jewish residents. |

Early Jewish Life in Jackson

The Jewish merchants and peddlers of the 19th-century United States were highly mobile, and records do not indicate who the first Jewish person in the Jackson area was. Only one of the original officers of Jackson’s Jewish congregation, Isadore Strauss, is known to have lived in Jackson prior to 1850. He spent several intervening years in Port Gibson before settling permanently in the city in 1855. Elias Bloom, a founding member of the congregation, is the only one listed as an enslaver in the 1860 Federal Slave Schedule. This low frequency of recorded slave ownership further suggests that Jackson Jews were not yet as economically established as their counterparts in Natchez or Vicksburg.

Although Jackson’s Jewish population was not as long-standing as those in some other Mississippi towns, they quickly set about establishing Jewish institutions. In 1860 local Jewish merchants bought land for a future Jewish cemetery on North State Street. The next year, fifteen families formally organized the Beth Israel Congregation. The congregation met in a one-story schoolhouse on South State Street and started the first Jewish day school in Mississippi. At the time, state public schools were nonexistent.

Although Jackson’s Jewish population was not as long-standing as those in some other Mississippi towns, they quickly set about establishing Jewish institutions. In 1860 local Jewish merchants bought land for a future Jewish cemetery on North State Street. The next year, fifteen families formally organized the Beth Israel Congregation. The congregation met in a one-story schoolhouse on South State Street and started the first Jewish day school in Mississippi. At the time, state public schools were nonexistent.

Beth Israel Congregation began as a traditional Orthodox group—in need of a teacher, chazzan (song leader), and shochet (kosher slaughterer)—but joined the Reform movement by 1875. In 1874, the wooden building that housed the congregation and its school burned down. It was replaced by a new brick building in 1875.

There has never been more than one congregation in Jackson, but Beth Israel has encountered periods of internal conflict. Shortly after the Civil War, a congregant wrote that the congregation’s approximately 50 members were divided between “Bavarians and Polanders,” as well as between newer arrivals and more established residents. Questions of religious practice fueled some of these early disagreements, with one contingent of members preferring traditional practices while another wished to adopt Isaac Mayer Wise’s Reform prayer book, Minhag America. Beth Israel Congregation ultimately moved toward Reform practice in the early 1870s under the leadership of their first rabbi, Reverend L. Winter.

During the late 1870s Beth Israel Congregation was unable to secure full-time rabbinical services. The congregation consisted of approximately 12 families with a total of roughly 75 individuals, who by 1879 had disbanded their school and did not always attract enough participants to hold Friday night services. Although a new religious school began operating in 1880, Jackson Jews continued to rely on lay leaders and student rabbis for much of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

There has never been more than one congregation in Jackson, but Beth Israel has encountered periods of internal conflict. Shortly after the Civil War, a congregant wrote that the congregation’s approximately 50 members were divided between “Bavarians and Polanders,” as well as between newer arrivals and more established residents. Questions of religious practice fueled some of these early disagreements, with one contingent of members preferring traditional practices while another wished to adopt Isaac Mayer Wise’s Reform prayer book, Minhag America. Beth Israel Congregation ultimately moved toward Reform practice in the early 1870s under the leadership of their first rabbi, Reverend L. Winter.

During the late 1870s Beth Israel Congregation was unable to secure full-time rabbinical services. The congregation consisted of approximately 12 families with a total of roughly 75 individuals, who by 1879 had disbanded their school and did not always attract enough participants to hold Friday night services. Although a new religious school began operating in 1880, Jackson Jews continued to rely on lay leaders and student rabbis for much of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Jewish Businesses in Jackson

Despite their small population, Jews were an important part of Jackson's merchant class. Most of Jackson’s earliest Jewish residents owned businesses in downtown Jackson, and that trend continued into the 20th century. At one time, Capitol Street was home to 16 Jewish businesses, none of which survived to the 21st century. As of 2021, only the restored storefront of the Cohen Brothers clothing store is immediately recognizable. In 1889, 15-year-old Moise Cohen came to Jackson from Romania to join his brother Sam in the clothing business. For almost a century, the Cohen Brothers’ clothing store served customers on Capitol Street. Other Jewish-owned downtown businesses included The Hub (owned by Harry Herman), Millstein’s Ready to Wear (Sam Millstein), Mangel's (owned by the Horowitz family), Vogue (owned by the Gordons), Lefkowitz Jewelry, and a farm supply store owned by the Ascher family.

In the 1920s, Jackson’s leading department store was The Emporium, located on the northeast corner of Congress and Capitol Streets. Its owner, Simon Seelig Marks, belonged to the Kiwanis Club and served as director of the Mississippi Merchants Association and vice president of Jackson’s Chamber of Commerce. He was married to Josephine Hyams of Jackson. During the Great Depression, Marks was also the state director for the National Emergency Council. The Emporium sold a wide range of inventory, including victory war bonds during World War II. Although long since closed, the building was restored in 1988, and it is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

In the 1920s, Jackson’s leading department store was The Emporium, located on the northeast corner of Congress and Capitol Streets. Its owner, Simon Seelig Marks, belonged to the Kiwanis Club and served as director of the Mississippi Merchants Association and vice president of Jackson’s Chamber of Commerce. He was married to Josephine Hyams of Jackson. During the Great Depression, Marks was also the state director for the National Emergency Council. The Emporium sold a wide range of inventory, including victory war bonds during World War II. Although long since closed, the building was restored in 1988, and it is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Jews were also involved in the apparel cleaning business in Jackson. Near the turn of the century, Mississippi native Isidore Lehman began his career in Jackson operating a shirt washing cart for a Memphis laundry company. He eventually became partner and owner of Jackson Steam Laundry. The business not only cleaned clothes, but it also served as a bathhouse for people without running water. As Lehman found financial success, he also contributed to Jackson’s civic life. He was president of numerous organizations including the Jackson and Mississippi Chambers of Commerce as well as Beth Israel synagogue, Hinds County Red Cross, and the local school board. Jackson Steam Laundry closed in the 1960s.

As Jackson Jews established themselves in business, they also invested in real estate. In the economic uncertainty that followed the Civil War, many Jews saw an opportunity to purchase cheap land. John Hart (formerly Hertz) was one of these buyers. In the 1850s, Hart had been a poor immigrant making $10 a month in a butcher shop. After serving in Company A of the 6th Mississippi Brigade, Hart used land purchases to increase his wealth and formed J & B Hart Company in 1866.

Joseph Ascher was another real estate success. Born in Alsace in 1855, he came to Jackson to live with relatives in the Hart family. Ascher began his career in the U.S. as a peddler but developed a prosperous real estate business by the end of his life. He also served on the Jackson School Board, embodying Jackson Jews’ interest in civic engagement and public service.

Jews enjoyed tremendous economic success in Jackson. Families such as Strauss, Norman, Beck, Feibleman, Kahn, Bloom, Wolf, Lehman, Hatry, and Devy lived in large houses on prime properties along North State Street.

As Jackson Jews established themselves in business, they also invested in real estate. In the economic uncertainty that followed the Civil War, many Jews saw an opportunity to purchase cheap land. John Hart (formerly Hertz) was one of these buyers. In the 1850s, Hart had been a poor immigrant making $10 a month in a butcher shop. After serving in Company A of the 6th Mississippi Brigade, Hart used land purchases to increase his wealth and formed J & B Hart Company in 1866.

Joseph Ascher was another real estate success. Born in Alsace in 1855, he came to Jackson to live with relatives in the Hart family. Ascher began his career in the U.S. as a peddler but developed a prosperous real estate business by the end of his life. He also served on the Jackson School Board, embodying Jackson Jews’ interest in civic engagement and public service.

Jews enjoyed tremendous economic success in Jackson. Families such as Strauss, Norman, Beck, Feibleman, Kahn, Bloom, Wolf, Lehman, Hatry, and Devy lived in large houses on prime properties along North State Street.

Congregational Growth

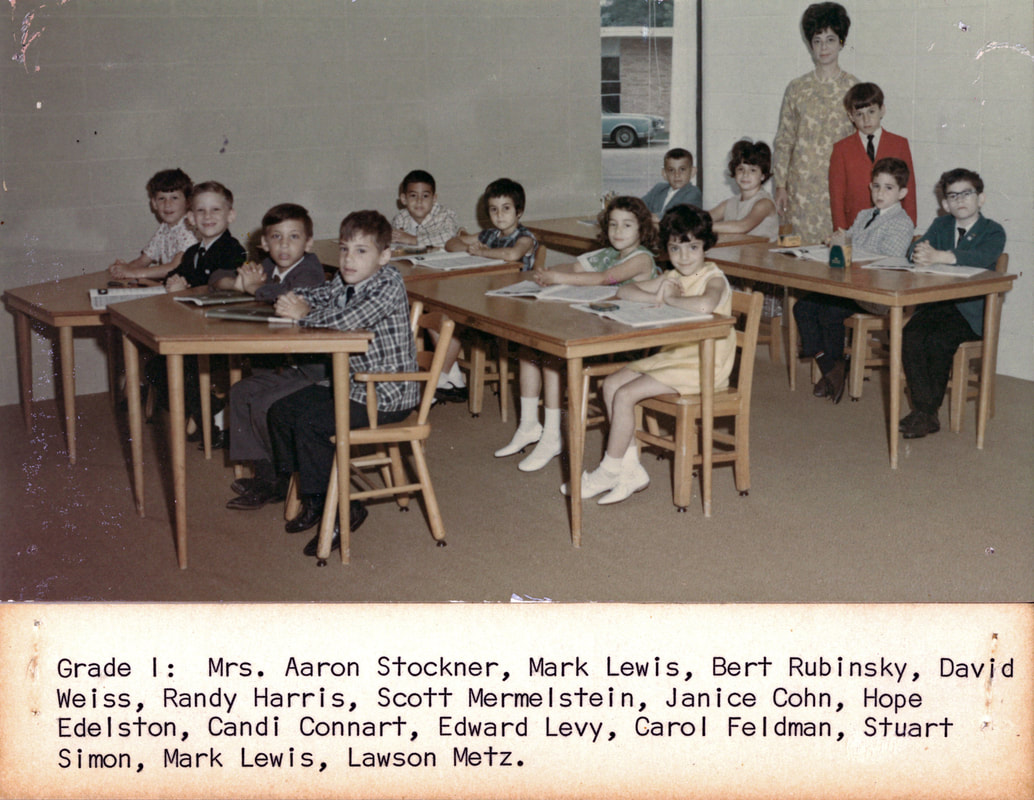

Beth Israel Religious School students with adults, c. 1920s. Beth Israel Congregation Archives.

Beth Israel Religious School students with adults, c. 1920s. Beth Israel Congregation Archives.

Jackson’s Jewish population fluctuated in the first decades of the 20th century, despite the growth of the city’s general population. Slightly fewer than 8,000 people lived in Jackson in 1900; during the next decade, the city grew to a population of 21,000. Beth Israel reached a membership of 37 households in 1907 but declined in size over the following twelve years. The congregation experienced high rabbinical turnover as well. When Jackson underwent another period of rapid growth in the 1920s, the number of Jewish households followed suit, and Beth Israel reached a membership of 41 families by 1930.

The relative Jewish boom of the 1920s improved Beth Israel’s financial situation and helped the congregation to retain a long-term rabbi, Meyer Lovitt. Rabbi Lovitt arrived in 1929 and served the Jackson congregation for 25 years. As early as 1926, the members of Beth Israel also began to discuss building a new synagogue. Many of them had moved away from the South State Street neighborhood where the Jewish population had been concentrated when the temple was built more than 50 years earlier. However, it took the congregation several years to raise the necessary funds and sell the old building. When the State Street temple was finally sold in 1940, it was the oldest religious structure still in use in the city, and the building was torn down soon after the sale. The new synagogue on Woodrow Wilson Drive—about two-and-a-half miles north on State Street—was closer to members’ homes at the time.

The Jewish population continued to increase during and after World War II, and Beth Israel Congregation boasted 150 families by 1962. In order to accommodate the booming religious school population, the congregation added five additional classrooms to its synagogue in 1955, just thirteen years after its dedication. By this point Beth Israel was one of the leading congregations in the state. When the congregation celebrated its centennial in 1961, Jackson Mayor Allen Thompson and Mississippi Governor Ross Barnett (both ardent segregationists) made remarks at a lavish Saturday-night banquet.

The relative Jewish boom of the 1920s improved Beth Israel’s financial situation and helped the congregation to retain a long-term rabbi, Meyer Lovitt. Rabbi Lovitt arrived in 1929 and served the Jackson congregation for 25 years. As early as 1926, the members of Beth Israel also began to discuss building a new synagogue. Many of them had moved away from the South State Street neighborhood where the Jewish population had been concentrated when the temple was built more than 50 years earlier. However, it took the congregation several years to raise the necessary funds and sell the old building. When the State Street temple was finally sold in 1940, it was the oldest religious structure still in use in the city, and the building was torn down soon after the sale. The new synagogue on Woodrow Wilson Drive—about two-and-a-half miles north on State Street—was closer to members’ homes at the time.

The Jewish population continued to increase during and after World War II, and Beth Israel Congregation boasted 150 families by 1962. In order to accommodate the booming religious school population, the congregation added five additional classrooms to its synagogue in 1955, just thirteen years after its dedication. By this point Beth Israel was one of the leading congregations in the state. When the congregation celebrated its centennial in 1961, Jackson Mayor Allen Thompson and Mississippi Governor Ross Barnett (both ardent segregationists) made remarks at a lavish Saturday-night banquet.

Civic Engagement and Jewish Social Status

Those Jackson Jews who found financial success often became involved in civic affairs. In the case of the Lehmans, that leadership became a family tradition. During the Great Depression, the Lehman family served breakfast to hungry children who attended the school across the street from the family's home. Aaron and Celestine Lehman (Isidore’s parents) started a home for elderly women in Jackson, and Aaron served on the Jackson school board. Celeste Lehman Orkin, Isidore Lehman's oldest daughter, was committed to preserving Jewish life in the Deep South, and helped found the youth movement for Jewish children in the area in the 1950s. Beginning in 1959 she was also the guiding force in the creation of Henry S. Jacobs Camp (now URJ Jacobs Camp) in nearby Utica, Mississippi.

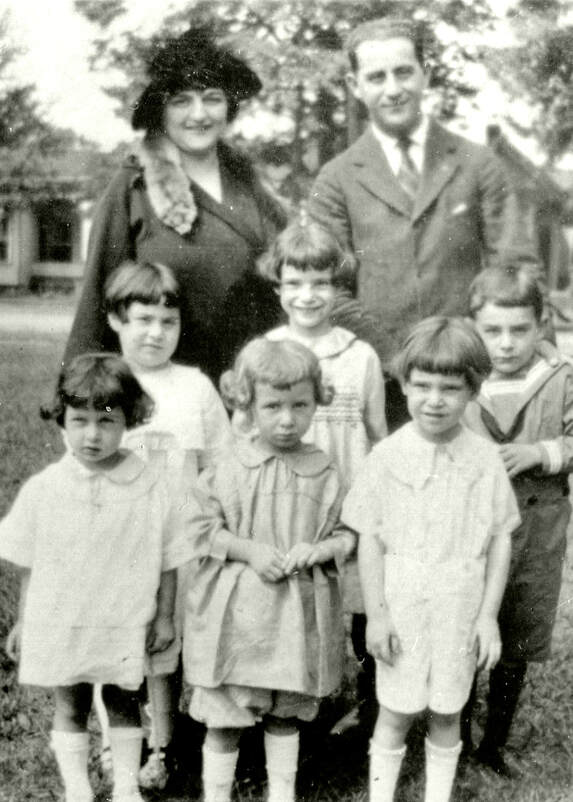

The Lehman sisters: Celeste Orkin, Bea Gotthelf, and Phyllis Herman.

Photo by Bill Aron.

The Lehman sisters: Celeste Orkin, Bea Gotthelf, and Phyllis Herman.

Photo by Bill Aron.

While the Lehman family had an exceptional record of public service, they were far from the only Jackson Jews to earn recognition in the wider community. Jewish businessmen in Jackson belonged to fraternal and civic groups including the Masons and the Odd Fellows. Local newspapers reported Jewish lifecycle events and business successes. Jackson Jews also worked to acculturate into white southern culture, dropping dietary laws and strict Shabbat observance. (The Jackson congregation had long held Shabbat services only on Friday evenings because so many store-owning members worked on Saturday mornings.)

Jackson Jews’ social acceptance and civic recognition was contingent on their adherence to the systems of racial segregation that structured everyday life in Mississippi. Black residents made up 40 to 50 percent of the city’s population during the first half of the 20th century, but white leaders at the local and state level ensured that they did not gain commensurate political or economic power. Although some local Jews proved more progressive on racial issues than their white Christian counterparts, they rarely challenged the status quo in a public manner. Jackson Jews employed Black workers in their homes and businesses in similar capacities as other white people of similar class standing. As they did elsewhere in the South, Jewish children attended all-white schools. Jewish-owned downtown stores followed the prevailing norms in their unequal treatment of Black and white customers.

Despite most Jackson Jews’ apparent success in entering the city’s white middle class, they encountered barriers to joining some of Jackson's elite white institutions. In the 1930s Bea (Lehman) Gotthelf received an unwelcome shock when she was snubbed by selective high school sororities. When Sam Millstein sold his retail businesses and started a real estate firm in 1954, he was not initially invited to join the Jackson Board of Realtors. Additionally, the Jackson Country Club did not accept its first Jewish members until the late 1970s or early 1980s.

Jackson Jews’ social acceptance and civic recognition was contingent on their adherence to the systems of racial segregation that structured everyday life in Mississippi. Black residents made up 40 to 50 percent of the city’s population during the first half of the 20th century, but white leaders at the local and state level ensured that they did not gain commensurate political or economic power. Although some local Jews proved more progressive on racial issues than their white Christian counterparts, they rarely challenged the status quo in a public manner. Jackson Jews employed Black workers in their homes and businesses in similar capacities as other white people of similar class standing. As they did elsewhere in the South, Jewish children attended all-white schools. Jewish-owned downtown stores followed the prevailing norms in their unequal treatment of Black and white customers.

Despite most Jackson Jews’ apparent success in entering the city’s white middle class, they encountered barriers to joining some of Jackson's elite white institutions. In the 1930s Bea (Lehman) Gotthelf received an unwelcome shock when she was snubbed by selective high school sororities. When Sam Millstein sold his retail businesses and started a real estate firm in 1954, he was not initially invited to join the Jackson Board of Realtors. Additionally, the Jackson Country Club did not accept its first Jewish members until the late 1970s or early 1980s.

The 1950s and 1960s

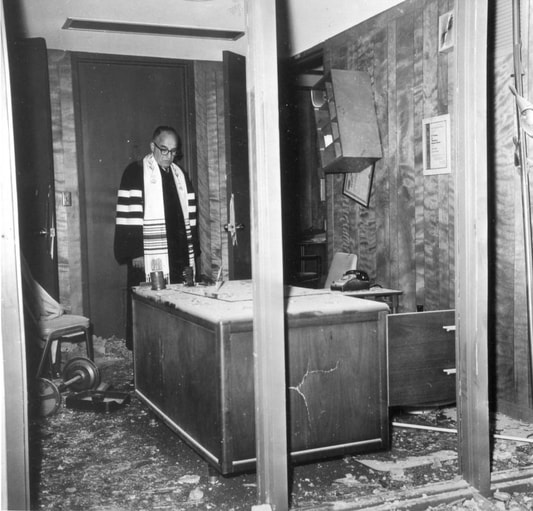

Rabbi Perry Nussbaum surveys damage at Beth Israel Congregation following the bombing on September 18, 1967. Photo by Jim Lucas.

Rabbi Perry Nussbaum surveys damage at Beth Israel Congregation following the bombing on September 18, 1967. Photo by Jim Lucas.

After Black civil rights activism increased during the mid-1950s, Jewish southerners faced competing pressures from pro- and anti-segregationist forces. National Jewish groups such as B’nai B’rith publicly supported the NAACP’s efforts to fight segregation in the courts. Both northern Jewish liberals and some Black civil rights organizers expressed disappointment in southern Jews’ reluctance to contribute to the cause. At the same time, antisemitic conspiracy theories circulated among the South’s hardline segregationist groups. Whether Jewish merchants and communal leaders endorsed segregation or not, they faced the possibility of economic boycotts and retaliatory violence if the Jewish community became identified with the Civil ights Movement.

Jackson Jews responded to the dilemma in a variety of ways. A few actively supported desegregation. Bea (daughter of Isidore and Gussie Lehman) and Harold Gotthelf, for example, belonged to cross-racial organizations that sought to advance racial equality. On one occasion, a member of the segregationist White Citizens Council called Harold on the phone and pressured him to fire a Black employee whose child was involved in civil rights activism. When Harold refused, the caller responded with a veiled threat.

Unlike the Gotthelf family, Ernst Borinski did not associate much with the Jewish community. Borinski escaped from Nazi Germany in 1938 and took a job teaching sociology at Tougaloo College (a private, historically Black college) in North Jackson in 1947. Over the subsequent decades he served as a mentor for a number of significant Black scholars and activists, and he convened integrated academic events on the Tougaloo campus when crossing the color line remained taboo in Mississippi.

Other Jackson Jews vocally supported segregation. Jewish attorney Alvin Binder was a Clarksdale native who advocated for the maintenance of segregation in the early 1960s. He made public appearances on behalf of the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission—a state-level agency tasked with anti-civil rights surveillance and public relations—and he helped to prosecute civil rights activists arrested during the Freedom Rides in 1961. Although Binder reported an eventual change of heart, he was not the only member of Beth Israel Congregation who endorsed segregation. Additionally, even those Jackson Jews who supported the basic idea of Black legal equality often disapproved of the direct action tactics adopted by civil rights organizations.

As the United States entered the peak years of civil rights activity, Beth Israel Congregation hired a new rabbi who would remain in Jackson until the early 1970s. Rabbi Perry Nussbaum had served for short periods at several synagogues before his arrival in Jackson in 1954. He was known for being rigid, and he ruffled feathers in Jackson by insisting on greater ritual observance at the congregation. Rabbi Nussbaum’s response to the problem of Black civil rights mirrored the approach of the majority of his congregants: avoiding public stances on desegregation that might attract unwanted attention to the Jewish community. Over time, however, he found it difficult to remain neutral. During the summer of 1961 he provided chaplain services to incarcerated Freedom Riders at Parchman Penitentiary. In 1964 he helped found the Committee of Concern, an interracial group of clergy who raised money to rebuild Black churches that had been bombed or burned by white supremacists. On some occasions he also addressed issues of racial justice in his sermons.

Jackson Jews responded to the dilemma in a variety of ways. A few actively supported desegregation. Bea (daughter of Isidore and Gussie Lehman) and Harold Gotthelf, for example, belonged to cross-racial organizations that sought to advance racial equality. On one occasion, a member of the segregationist White Citizens Council called Harold on the phone and pressured him to fire a Black employee whose child was involved in civil rights activism. When Harold refused, the caller responded with a veiled threat.

Unlike the Gotthelf family, Ernst Borinski did not associate much with the Jewish community. Borinski escaped from Nazi Germany in 1938 and took a job teaching sociology at Tougaloo College (a private, historically Black college) in North Jackson in 1947. Over the subsequent decades he served as a mentor for a number of significant Black scholars and activists, and he convened integrated academic events on the Tougaloo campus when crossing the color line remained taboo in Mississippi.

Other Jackson Jews vocally supported segregation. Jewish attorney Alvin Binder was a Clarksdale native who advocated for the maintenance of segregation in the early 1960s. He made public appearances on behalf of the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission—a state-level agency tasked with anti-civil rights surveillance and public relations—and he helped to prosecute civil rights activists arrested during the Freedom Rides in 1961. Although Binder reported an eventual change of heart, he was not the only member of Beth Israel Congregation who endorsed segregation. Additionally, even those Jackson Jews who supported the basic idea of Black legal equality often disapproved of the direct action tactics adopted by civil rights organizations.

As the United States entered the peak years of civil rights activity, Beth Israel Congregation hired a new rabbi who would remain in Jackson until the early 1970s. Rabbi Perry Nussbaum had served for short periods at several synagogues before his arrival in Jackson in 1954. He was known for being rigid, and he ruffled feathers in Jackson by insisting on greater ritual observance at the congregation. Rabbi Nussbaum’s response to the problem of Black civil rights mirrored the approach of the majority of his congregants: avoiding public stances on desegregation that might attract unwanted attention to the Jewish community. Over time, however, he found it difficult to remain neutral. During the summer of 1961 he provided chaplain services to incarcerated Freedom Riders at Parchman Penitentiary. In 1964 he helped found the Committee of Concern, an interracial group of clergy who raised money to rebuild Black churches that had been bombed or burned by white supremacists. On some occasions he also addressed issues of racial justice in his sermons.

Meanwhile, Jackson’s Jewish population continued to grow. In 1965 Beth Israel Congregation broke ground on a new synagogue building in Northeast Jackson, near the newly-developed residential neighborhoods that were attracting many of the city’s Jewish families. The sanctuary had capacity for 230 people, and a set of retractable walls allowed for overflow seating in the adjacent social hall. At the March 1967 dedication ceremonies, African American ministers from prominent local churches participated along with white Christian clergy.

By that time, Rabbi Nussbaum’s civil rights activities had attracted the attention of segregationist terrorists. On the night of September 18th, 1967, a group of Ku Klux Klan members planted a bomb that destroyed much of the Rabbi’s office and part of the library. The synagogue was empty at the time, and no one was injured. Two months later, the same Klan members bombed the Nussbaum home while the rabbi was home with his wife. Miraculously, again, no one was hurt. In 1968 the same terror cell bombed the temple in Meridian, Mississippi, and the culprits were eventually apprehended when they tried to bomb the home of a Jewish leader in Meridian.

To some extent, the Beth Israel bombings were a turning point, as many white Jacksonians—Jewish and non-Jewish alike—decided that the violence of massive resistance had gone too far. In response to the bombing of the Nussbaum home, 42 clergymen and sympathetic citizens joined in a “walk of penance” to Beth Israel. There they held a Thursday night vigil, which attracted a crowd of 150 people, most of whom were not Jewish. Local newspapers and state officials denounced the attacks and expressed support for Beth Israel. (Earlier bombings of and arson attacks against Black churches drew far less attention). In 1968, a full page ad in Jackson’s daily newspaper called for an end to “hate, discord [and] violence” in the city. The ad was signed by numerous civic and business leaders, including more than a dozen Jewish professionals and business owners. While the bombings may have pushed Jackson Jews to become more engaged with civic issues, the violence also caused Rabbi Nussbaum to curtail his advocacy and look for another pulpit. He received no job offers, however, and remained in Jackson until his retirement in 1973.

By that time, Rabbi Nussbaum’s civil rights activities had attracted the attention of segregationist terrorists. On the night of September 18th, 1967, a group of Ku Klux Klan members planted a bomb that destroyed much of the Rabbi’s office and part of the library. The synagogue was empty at the time, and no one was injured. Two months later, the same Klan members bombed the Nussbaum home while the rabbi was home with his wife. Miraculously, again, no one was hurt. In 1968 the same terror cell bombed the temple in Meridian, Mississippi, and the culprits were eventually apprehended when they tried to bomb the home of a Jewish leader in Meridian.

To some extent, the Beth Israel bombings were a turning point, as many white Jacksonians—Jewish and non-Jewish alike—decided that the violence of massive resistance had gone too far. In response to the bombing of the Nussbaum home, 42 clergymen and sympathetic citizens joined in a “walk of penance” to Beth Israel. There they held a Thursday night vigil, which attracted a crowd of 150 people, most of whom were not Jewish. Local newspapers and state officials denounced the attacks and expressed support for Beth Israel. (Earlier bombings of and arson attacks against Black churches drew far less attention). In 1968, a full page ad in Jackson’s daily newspaper called for an end to “hate, discord [and] violence” in the city. The ad was signed by numerous civic and business leaders, including more than a dozen Jewish professionals and business owners. While the bombings may have pushed Jackson Jews to become more engaged with civic issues, the violence also caused Rabbi Nussbaum to curtail his advocacy and look for another pulpit. He received no job offers, however, and remained in Jackson until his retirement in 1973.

The Late 20th Century

Jackson’s Jewish population continued to grow in the 1970s and 1980s, in contrast with shrinking Jewish communities elsewhere in Mississippi. Following the departure of Rabbi Nussbaum, Beth Israel Congregation hired Rabbi Richard Birnholz, who had been an assistant rabbi in Memphis. Rabbi Birnholz’s 13-year tenure was marked by stability and growth. In addition to religious practice, the congregation and its members participated in a variety of interfaith events and organizations. The annual Sisterhood Bazaar fundraiser, which had begun in 1967, continued to attract a large public audience for a day-long sale of Jewish foods that benefited local charities. Beth Israel also opened a preschool in its synagogue in 1975, which soon attracted a diverse student body. The preschool did not offer a Jewish curriculum; it was the only secular early childhood education option in the city at the time.

While Beth Israel emerged as the largest Jewish congregation in the state, the late 20th century brought significant changes to the Jackson metro area and its Jewish population. Whereas many Jewish families had once made their livings in retail, a greater number of Jewish workers held jobs in medicine, law, and higher education. Following a 1970 court decision that mandated the full desegregation of Jackson Public Schools, white parents in the area increasingly sought other options. Many Jewish families participated in the exodus, either enrolling their children in private schools or relocating to the growing suburbs. Jackson itself began to lose population around 1980, a trend which continued into the 21st century. The 1993-1994 religious school roster for Beth Israel Congregation reflects both the process of white out-migration from Jackson and the city’s heightened role as a hub for Jewish Mississippians. Of the 108 religious school students listed, a majority (66) lived in Jackson, with 31 from nearby suburbs and the remainder (11) from more distant small towns.

Jewish practice also changed in Jackson during the late 20th century. Beth Israel Congregation, like many southern synagogues, remained a haven of Classical Reform Judaism into the 1970s. Friday night services took precedence over Saturday mornings. Holiday observances featured a choir, which sang with organ accompaniment and was hidden by a screen at the back of the bema. Services consisted primarily of English-language prayers. However, a number of Classical Reform elements began to change by the end of the century. B’nai mitzvah ceremonies became commonplace, piano accompaniment replaced the organ, and services featured more Hebrew prayers than in the past. The shift toward more contemporary Reform practices continued into the next century.

Jewish practice also changed in Jackson during the late 20th century. Beth Israel Congregation, like many southern synagogues, remained a haven of Classical Reform Judaism into the 1970s. Friday night services took precedence over Saturday mornings. Holiday observances featured a choir, which sang with organ accompaniment and was hidden by a screen at the back of the bema. Services consisted primarily of English-language prayers. However, a number of Classical Reform elements began to change by the end of the century. B’nai mitzvah ceremonies became commonplace, piano accompaniment replaced the organ, and services featured more Hebrew prayers than in the past. The shift toward more contemporary Reform practices continued into the next century.

The Early 21st Century

Jackson’s Jewish population peaked sometime around 2010, when Beth Israel Congregation’s membership surpassed 220 member households and 600 individuals. Local Jews continued to play prominent roles in civic, cultural, and charitable organizations, whether serving on the school board or the boards of museums and theater companies. The suburbanization of previous decades also persisted, with Jewish households distributed among several municipalities.

In the early 21st century, the nearby presence of URJ Jacobs Camp in Utica continues to enhance Jewish life in Jackson. Camp staff often live in Jackson during the off-season, and Jewish children in Jackson have a high camp attendance rate. In addition to the camp, Jackson has been home to the Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life (ISJL)—founded by former camp director Macy B. Hart—since 2000. In addition to young staff members who typically work at the ISJL for two years after college, the organization has attracted a handful of Jewish families who have settled in Jackson permanently.

Beth Israel Congregation’s membership decreased during the 2010s. As of 2021 the membership includes approximately 170 households representing 300 individuals. The decline occurred due to both deaths among the older generation of members (especially those above 80) and relocations among younger members (empty nesters and younger adults alike). When the sisterhood dissolved in 2020, shrinking enrollment played a role, but so did changing lifestyle patterns and gender norms; Jewish professional women in their 30s and 40s had less availability for daytime sisterhood events, and they were better represented in the general leadership of the congregation. The annual Bazaar had changed from a Sisterhood event to a congregational one several years earlier, and local Jewish men had gotten involved with more of the cooking duties.

Despite these and other changes, Beth Israel Congregation maintains an active calendar and remains the largest Jewish congregation in the state. In 2019 the congregation hired a new full-time rabbi, Joseph Rosen, and the religious school continues to enroll approximately 20 students. While Jewish life should persist in the Jackson area for the foreseeable future, the size and vibrancy of the Jewish community will likely depend on the fortunes of Mississippi's capital city.

In the early 21st century, the nearby presence of URJ Jacobs Camp in Utica continues to enhance Jewish life in Jackson. Camp staff often live in Jackson during the off-season, and Jewish children in Jackson have a high camp attendance rate. In addition to the camp, Jackson has been home to the Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life (ISJL)—founded by former camp director Macy B. Hart—since 2000. In addition to young staff members who typically work at the ISJL for two years after college, the organization has attracted a handful of Jewish families who have settled in Jackson permanently.

Beth Israel Congregation’s membership decreased during the 2010s. As of 2021 the membership includes approximately 170 households representing 300 individuals. The decline occurred due to both deaths among the older generation of members (especially those above 80) and relocations among younger members (empty nesters and younger adults alike). When the sisterhood dissolved in 2020, shrinking enrollment played a role, but so did changing lifestyle patterns and gender norms; Jewish professional women in their 30s and 40s had less availability for daytime sisterhood events, and they were better represented in the general leadership of the congregation. The annual Bazaar had changed from a Sisterhood event to a congregational one several years earlier, and local Jewish men had gotten involved with more of the cooking duties.

Despite these and other changes, Beth Israel Congregation maintains an active calendar and remains the largest Jewish congregation in the state. In 2019 the congregation hired a new full-time rabbi, Joseph Rosen, and the religious school continues to enroll approximately 20 students. While Jewish life should persist in the Jackson area for the foreseeable future, the size and vibrancy of the Jewish community will likely depend on the fortunes of Mississippi's capital city.

Last updated, November 2021

Selected Bibliography

Stuart Rockoff, Beth Israel Congregation 150th Anniversary, 1861-2011, (Jackson, MS).

Jack Nelson, Terror in the Night: The Klan's Campaign Against the Jews (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1993).

Leo E. and Evelyn Turitz, Jews in Early Mississippi (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 1983).

Clive Webb, Fight Against Fear: Southern Jews and Black Civil Rights (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2003).

Stuart Rockoff, Beth Israel Congregation 150th Anniversary, 1861-2011, (Jackson, MS).

Jack Nelson, Terror in the Night: The Klan's Campaign Against the Jews (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1993).

Leo E. and Evelyn Turitz, Jews in Early Mississippi (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 1983).

Clive Webb, Fight Against Fear: Southern Jews and Black Civil Rights (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2003).