Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Knoxville, Tennessee

Knoxville: Historical Overview

|

Over the past several decades, the Jewish South has been transformed, as generations of Jewish merchants have given way to Jewish professionals and executives. Knoxville, with its long history as a small Jewish community in East Tennessee and its recent emergence as a part of the Jewish sunbelt boom, perfectly encapsulates these demographic changes. In this way, the story of Jewish Knoxville is the story of the Jewish South writ large.

Founded in 1796, Knoxville was the capital of the newly admitted western state of Tennessee for its first 20 years. Located in the foothills of the Great Smokey Mountains, Knoxville never developed large-scale slavery or plantation agriculture. For this reason, the area was strongly Unionist during the Civil War, and offered little resistance when the Union occupied Knoxville. The history of Jews in East Tennessee would have begun a century earlier than it did if Sir Alexander Cuming had his way. A Scottish adventurer, Cuming hatched an impractical scheme to colonize 300,000 European Jewish families in East Tennessee. Far from a humanitarian or proto-Zionist, Cuming hoped to enrich himself from this money-making venture. He brought his idea to London Jews, who failed to express much enthusiasm for the plan. King George II didn’t like it either, and nothing became of Cuming’s scheme. The history of Jewish life in the area around Knoxville thus unfolded according to the general pattern of Jewish settlement in the Southern interior. A strong Jewish community exists in Knoxville today. |

RESOURCES

Chabad of Knoxville website Heska Amuna Synagogue website Temple Beth El website Photos courtesy of the Knoxville Jewish Archives |

Stories of the Jewish Community in Knoxville

Early Jewish Residents

The Civil War was a catalyst in the development of Knoxville’s Jewish community. On the eve of the war, there were seven Jewish families living among Knoxville’s 3,000 residents. One of these was A. Schwab, a merchant who emigrated from France sometime before 1844 and settled in Tennessee by the early 1850s. In 1861, his 18-year-old son, Joseph, died while fighting for the Confederacy in Virginia. Schwab wanted to bury his son in Knoxville, but there was no Jewish cemetery in town. Solomon Lyon and Joseph Mayer, two Jewish merchants who owned a store together, donated a small parcel of land for Schwab’s burial and for use as a Jewish cemetery. In 1864, Knoxville Jews established a Hebrew Benevolent Society to oversee the cemetery and care for local Jews in need. This group soon began to hold worship services and eventually grew into Knoxville’s first Jewish congregation.

After the Civil War, a growing number of Jews settled in Knoxville. Louis Gratz, a German immigrant who lived in the North and volunteered for the Union Army, was stationed in East Tennessee at the end of the war. While in Knoxville, he fell in love with the daughter of a prominent local family, married her, and remained in town. Gratz was a lawyer and also owned a grocery store. He twice served as city attorney and was elected mayor of North Knoxville four times starting in the 1890s. Gratz’s wife was not Jewish and he had little contact with the burgeoning Jewish community in Knoxville. Gratz’s life reflected the freedom and opportunities available to Jews; this included to freedom to leave the Jewish community.

Gratz was just one of several Jews who found their way to Knoxville after the war. In the late 1860s, Bavarian immigrant Julius Ochs and family moved from Cincinnati to Knoxville, where they had lived briefly in the 1850s. Julius tried various business ventures which usually resulted in failure. His son Adolph started working as a paperboy for the Knoxville Chronicle, and worked his way up to being a journeyman typesetter by the time he was 17. In 1877, when he was only 19, Adolph moved to Chattanooga, and borrowed $250 to buy a controlling share of the Chattanooga Times, which became very successful under his stewardship. Ochs later married Effie Wise, the daughter of the famous rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise. In 1896, he purchased the New York Times and built it into one of the most successful and respected newspapers in the world.

The Civil War was a catalyst in the development of Knoxville’s Jewish community. On the eve of the war, there were seven Jewish families living among Knoxville’s 3,000 residents. One of these was A. Schwab, a merchant who emigrated from France sometime before 1844 and settled in Tennessee by the early 1850s. In 1861, his 18-year-old son, Joseph, died while fighting for the Confederacy in Virginia. Schwab wanted to bury his son in Knoxville, but there was no Jewish cemetery in town. Solomon Lyon and Joseph Mayer, two Jewish merchants who owned a store together, donated a small parcel of land for Schwab’s burial and for use as a Jewish cemetery. In 1864, Knoxville Jews established a Hebrew Benevolent Society to oversee the cemetery and care for local Jews in need. This group soon began to hold worship services and eventually grew into Knoxville’s first Jewish congregation.

After the Civil War, a growing number of Jews settled in Knoxville. Louis Gratz, a German immigrant who lived in the North and volunteered for the Union Army, was stationed in East Tennessee at the end of the war. While in Knoxville, he fell in love with the daughter of a prominent local family, married her, and remained in town. Gratz was a lawyer and also owned a grocery store. He twice served as city attorney and was elected mayor of North Knoxville four times starting in the 1890s. Gratz’s wife was not Jewish and he had little contact with the burgeoning Jewish community in Knoxville. Gratz’s life reflected the freedom and opportunities available to Jews; this included to freedom to leave the Jewish community.

Gratz was just one of several Jews who found their way to Knoxville after the war. In the late 1860s, Bavarian immigrant Julius Ochs and family moved from Cincinnati to Knoxville, where they had lived briefly in the 1850s. Julius tried various business ventures which usually resulted in failure. His son Adolph started working as a paperboy for the Knoxville Chronicle, and worked his way up to being a journeyman typesetter by the time he was 17. In 1877, when he was only 19, Adolph moved to Chattanooga, and borrowed $250 to buy a controlling share of the Chattanooga Times, which became very successful under his stewardship. Ochs later married Effie Wise, the daughter of the famous rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise. In 1896, he purchased the New York Times and built it into one of the most successful and respected newspapers in the world.

The Community Grows

Eastern European Jews began to arrive in Knoxville in the late 19th century. Some came as peddlers sent by the wholesaling giant, the Baltimore Bargain House, which guided newly arrived immigrants to peddling routes in the country’s hinterlands. By 1880, so many Jewish peddlers were traveling through Knoxville that the newly formed Ladies Hebrew Benevolent Auxiliary raised money to help house and feed them. Some of these peddlers decided to settle in Knoxville; a number opened small stores downtown around Vine Street.

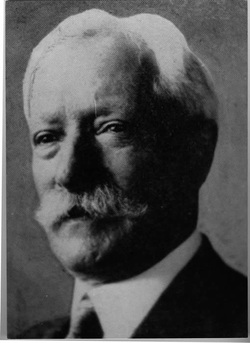

Another turning point in the Knoxville’s Jewish history took place in 1888, when Max Arnstein decided to stop in Knoxville, rather than continuing on to Birmingham, his planned destination. Arnstein had earlier owned a store in Anderson, South Carolina, and had heard of the tremendous economic opportunity that existed in Birmingham. On his way to Alabama, he stopped in Knoxville for the night. He liked the town and noticed several stores for rent. Casting his lot in East Tennessee, Arnstein opened a dry goods store called M.B. Arnstein & Company, which eventually grew into a hugely successful department store specializing in high-end goods. In 1905, he built a seven-story building in downtown Knoxville to house his store and business. Arnstein became an important civic leader and philanthropist whose family supported both Knoxville and its small Jewish community.

In the early 20th century, the Knoxville Jewish community was made up of a handful of often large families that were intermarried with each other. The Robinsons were one such family. Six brothers came from Russia before World War I, settling in Knoxville because they had an uncle already living there. One brother, S.H., opened a feed store, while the rest went into the junk business. Another brother, Frank Robinson, died in a horse and wagon accident while peddling in East Tennessee. They brought another brother, A.J., from Rhode Island to be the shochet (kosher butcher) for the growing Orthodox population. A.J. opened a small kosher butcher shop in downtown Knoxville. Max Robinson returned to Russia after World War I and brought their mother back to Knoxville.

Eastern European Jews began to arrive in Knoxville in the late 19th century. Some came as peddlers sent by the wholesaling giant, the Baltimore Bargain House, which guided newly arrived immigrants to peddling routes in the country’s hinterlands. By 1880, so many Jewish peddlers were traveling through Knoxville that the newly formed Ladies Hebrew Benevolent Auxiliary raised money to help house and feed them. Some of these peddlers decided to settle in Knoxville; a number opened small stores downtown around Vine Street.

Another turning point in the Knoxville’s Jewish history took place in 1888, when Max Arnstein decided to stop in Knoxville, rather than continuing on to Birmingham, his planned destination. Arnstein had earlier owned a store in Anderson, South Carolina, and had heard of the tremendous economic opportunity that existed in Birmingham. On his way to Alabama, he stopped in Knoxville for the night. He liked the town and noticed several stores for rent. Casting his lot in East Tennessee, Arnstein opened a dry goods store called M.B. Arnstein & Company, which eventually grew into a hugely successful department store specializing in high-end goods. In 1905, he built a seven-story building in downtown Knoxville to house his store and business. Arnstein became an important civic leader and philanthropist whose family supported both Knoxville and its small Jewish community.

In the early 20th century, the Knoxville Jewish community was made up of a handful of often large families that were intermarried with each other. The Robinsons were one such family. Six brothers came from Russia before World War I, settling in Knoxville because they had an uncle already living there. One brother, S.H., opened a feed store, while the rest went into the junk business. Another brother, Frank Robinson, died in a horse and wagon accident while peddling in East Tennessee. They brought another brother, A.J., from Rhode Island to be the shochet (kosher butcher) for the growing Orthodox population. A.J. opened a small kosher butcher shop in downtown Knoxville. Max Robinson returned to Russia after World War I and brought their mother back to Knoxville.

Organized Jewish Life in Knoxville

With their growing population, Knoxville Jews began to build religious institutions. In 1869, the Hebrew Benevolent Association held worship services once a month on Sundays in members’ homes and businesses. Julius Ochs was a leader of Knoxville’s Jewish congregation, often serving as lay reader. For a while, the group met at Jacob Spiro’s Cider and Vinegar Works Company, with worshipers sitting on vinegar barrels. This small group was Reform, using an organ and choir during services, and joined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations in 1875. In 1877, they changed their name to Beth El (House of God) and established a religious school that met in private homes. Despite its new name, the congregation did not have a house of its own, and continued to meet in rented and borrowed rooms. On the High Holidays, Beth El would meet in large halls like the Masonic Temple, the Lyceum Building, and sometimes the First Presbyterian Church. Beth El was very small. It had only 15 members in 1880, and couldn’t afford a full-time rabbi or synagogue. In 1888, they brought in their first student rabbi from Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati; HUC students continued to serve Beth El over the next 34 years.

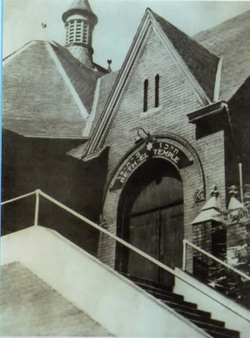

Not all Knoxville Jews were happy with the Reform worship style of Beth El. In 1890, a group of these dissenters joined with newly arriving immigrants from Eastern Europe to establish a traditional synagogue, Heska Amuna (Strongholders of the Faith). While Heska Amuna started with only ten founding members, it soon grew larger than the older congregation, Beth El. They hired their first rabbi, A. Michaelof, soon after organizing. By 1894, they had acquired a house on the corner of Vine and Temperance Streets for use as a synagogue. The following year they hired Isaac Winick as their rabbi, who lived in the synagogue’s upstairs area with his family. Winick was also a mohel (ritual circumciser), and traveled throughout the region performing circumcisions. In 1921, the congregation bought a new building on West Fifth Avenue.

In most other Southern communities with two synagogues, the older, Reform congregation was usually larger and more established. This was not the case in Knoxville. By 1900, Heska Amuna had a synagogue and a full-time rabbi, while the 36-year-old congregation Beth El had neither. In 1907, Heska Amuna had 75 members while Beth El only had 20. Finally, in 1914, after 50 years as a congregation, Beth El bought a former church for $5000 as its first synagogue. Max Arnstein was the largest donor in this fundraising campaign, which attracted several donations from local Gentiles. Beth El’s new synagogue had sanctuary seating for 200 and six classrooms. In 1922, Beth El hired its first rabbi, Jerome Mark, who came to Knoxville from the congregation in Helena, Arkansas. Their new synagogue and rabbi helped to fuel a growth in Beth El’s membership. By 1945, it had 98 members.

With their growing population, Knoxville Jews began to build religious institutions. In 1869, the Hebrew Benevolent Association held worship services once a month on Sundays in members’ homes and businesses. Julius Ochs was a leader of Knoxville’s Jewish congregation, often serving as lay reader. For a while, the group met at Jacob Spiro’s Cider and Vinegar Works Company, with worshipers sitting on vinegar barrels. This small group was Reform, using an organ and choir during services, and joined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations in 1875. In 1877, they changed their name to Beth El (House of God) and established a religious school that met in private homes. Despite its new name, the congregation did not have a house of its own, and continued to meet in rented and borrowed rooms. On the High Holidays, Beth El would meet in large halls like the Masonic Temple, the Lyceum Building, and sometimes the First Presbyterian Church. Beth El was very small. It had only 15 members in 1880, and couldn’t afford a full-time rabbi or synagogue. In 1888, they brought in their first student rabbi from Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati; HUC students continued to serve Beth El over the next 34 years.

Not all Knoxville Jews were happy with the Reform worship style of Beth El. In 1890, a group of these dissenters joined with newly arriving immigrants from Eastern Europe to establish a traditional synagogue, Heska Amuna (Strongholders of the Faith). While Heska Amuna started with only ten founding members, it soon grew larger than the older congregation, Beth El. They hired their first rabbi, A. Michaelof, soon after organizing. By 1894, they had acquired a house on the corner of Vine and Temperance Streets for use as a synagogue. The following year they hired Isaac Winick as their rabbi, who lived in the synagogue’s upstairs area with his family. Winick was also a mohel (ritual circumciser), and traveled throughout the region performing circumcisions. In 1921, the congregation bought a new building on West Fifth Avenue.

In most other Southern communities with two synagogues, the older, Reform congregation was usually larger and more established. This was not the case in Knoxville. By 1900, Heska Amuna had a synagogue and a full-time rabbi, while the 36-year-old congregation Beth El had neither. In 1907, Heska Amuna had 75 members while Beth El only had 20. Finally, in 1914, after 50 years as a congregation, Beth El bought a former church for $5000 as its first synagogue. Max Arnstein was the largest donor in this fundraising campaign, which attracted several donations from local Gentiles. Beth El’s new synagogue had sanctuary seating for 200 and six classrooms. In 1922, Beth El hired its first rabbi, Jerome Mark, who came to Knoxville from the congregation in Helena, Arkansas. Their new synagogue and rabbi helped to fuel a growth in Beth El’s membership. By 1945, it had 98 members.

While Heska Amuna was the stronger, more active congregation, it also experienced more internal dissension. In 1907, a group led by Rabbi Isaac Winickbroke away from Heska Amuna and formed a new congregation, Anshei Sholom (Men of Peace). The dispute seems to have been over the religious school. The 30 members of Anshei Sholom met for three years in a rented room on Vine Street, before rejoining Heska Amuna in 1910.

The congregation split again in 1929, this time over the issue of maintaining kashrut, the Jewish dietary laws. The congregation had been paying a local kosher butcher, A.J. Robinson, a monthly salary for his services, but decided to stop this practice. While still an Orthodox congregation, Heska Amuna had been adopting reforms, including mixed-gender seating. A group of 60 people upset about the firing of Robinson split from Heska Amuna and founded a new congregation called Beth Israel, which met, appropriately enough, above a kosher restaurant. Many of these dissidents belonged to the large Robinson, Green, or Slovis families. A.J. Robinson led services for the first few years before the congregation hired the young Orthodox rabbi Israel Levine, who instituted Hebrew classes for girls. Rabbi Levine stayed for five years, and was replaced by Morris Herzlich in 1937. The following year, Beth Israel disbanded and most of its members rejoined Heska Amuna.

Despite the turmoil within Heska Amuna, its relationship with Beth El was cordial. In the early 1900s, a Junior Jewish Social Club brought together the youth of both congregations. A tradition developed in which temple children would walk down to Heska Amuna after Rosh Hashanah services to visit their friends. This tradition continues today. Ben Winick, who belonged to Heska Amuna, sought to preserve these social connections into adulthood, founding the Progressive Club, a Jewish social and literary society for both Reform and Orthodox Jews. Started in 1923, the Progressive Club helped lead to the creation of a Jewish community center six years later. In 1930, the two synagogues founded a joint Sunday school. Led by William Shaw, a professor at the University of Tennessee and an ardent Zionist, the school focused on Jewish history and culture. Students from Heska Amuna also attended a weekday Hebrew School. The joint Sunday school lasted for over 20 years, until Rabbi Solomon Foster of Beth El pulled out of the arrangement and reestablished the Reform congregation’s own Sunday school.

This cooperation between the members of the different synagogues in Knoxville was reinforced by the creation of a Jewish Community Center in 1929. The JCC was the final gift of Max Arnstein to the Knoxville Jewish community before he retired and moved to New York. Arnstein donated a three-story building located next door to Temple Beth El for use as a Jewish Community Center. Although the building was technically owned by Beth El, the JCC became a central social and cultural meeting place for all young Jews in Knoxville. Its mission was to serve the spiritual, social, and educational needs of all Knoxville Jews and to promote “mutual understanding.” The JCC had a library, club rooms, game rooms, kitchen, gymnasium, and auditorium. It hosted a dance after the Yom Kippur break-the-fast and a big annual Purim Ball. In the 1960s, the Arnstein family gave the money to build a new JCC in west Knoxville. The JCC also housed the Federation of Jewish Charities, which was established in 1940 to provide assistance to Knoxville Jews in need.

The congregation split again in 1929, this time over the issue of maintaining kashrut, the Jewish dietary laws. The congregation had been paying a local kosher butcher, A.J. Robinson, a monthly salary for his services, but decided to stop this practice. While still an Orthodox congregation, Heska Amuna had been adopting reforms, including mixed-gender seating. A group of 60 people upset about the firing of Robinson split from Heska Amuna and founded a new congregation called Beth Israel, which met, appropriately enough, above a kosher restaurant. Many of these dissidents belonged to the large Robinson, Green, or Slovis families. A.J. Robinson led services for the first few years before the congregation hired the young Orthodox rabbi Israel Levine, who instituted Hebrew classes for girls. Rabbi Levine stayed for five years, and was replaced by Morris Herzlich in 1937. The following year, Beth Israel disbanded and most of its members rejoined Heska Amuna.

Despite the turmoil within Heska Amuna, its relationship with Beth El was cordial. In the early 1900s, a Junior Jewish Social Club brought together the youth of both congregations. A tradition developed in which temple children would walk down to Heska Amuna after Rosh Hashanah services to visit their friends. This tradition continues today. Ben Winick, who belonged to Heska Amuna, sought to preserve these social connections into adulthood, founding the Progressive Club, a Jewish social and literary society for both Reform and Orthodox Jews. Started in 1923, the Progressive Club helped lead to the creation of a Jewish community center six years later. In 1930, the two synagogues founded a joint Sunday school. Led by William Shaw, a professor at the University of Tennessee and an ardent Zionist, the school focused on Jewish history and culture. Students from Heska Amuna also attended a weekday Hebrew School. The joint Sunday school lasted for over 20 years, until Rabbi Solomon Foster of Beth El pulled out of the arrangement and reestablished the Reform congregation’s own Sunday school.

This cooperation between the members of the different synagogues in Knoxville was reinforced by the creation of a Jewish Community Center in 1929. The JCC was the final gift of Max Arnstein to the Knoxville Jewish community before he retired and moved to New York. Arnstein donated a three-story building located next door to Temple Beth El for use as a Jewish Community Center. Although the building was technically owned by Beth El, the JCC became a central social and cultural meeting place for all young Jews in Knoxville. Its mission was to serve the spiritual, social, and educational needs of all Knoxville Jews and to promote “mutual understanding.” The JCC had a library, club rooms, game rooms, kitchen, gymnasium, and auditorium. It hosted a dance after the Yom Kippur break-the-fast and a big annual Purim Ball. In the 1960s, the Arnstein family gave the money to build a new JCC in west Knoxville. The JCC also housed the Federation of Jewish Charities, which was established in 1940 to provide assistance to Knoxville Jews in need.

Eastern European Jews in Knoxville

Eastern European Jews in Knoxville followed the same path of upward mobility as the earlier German Jews had. Max Finklestein came to American from Poland in 1890, settling in Knoxville by 1895. He opened a clothing store which grew into a successful business, and later built the Finklestein Building in downtown Knoxville. Finklestein served as president of Heska Amuna and the local chapter of B’nai B’rith, and was also involved in several non-Jewish fraternal societies.

The path to success was not always short or easy. Oscar Glazer came to the U.S. from Russia before World War I, settling in Atlanta. After the lynching of Leo Frank, Glazer left Atlanta and moved to Knoxville, where he opened a small grocery store. The business closed in 1916 after Glazer’s bank failed. When America entered World War I, Glazer traveled the region buying scrap metal, which had become a hot commodity. Glazer managed to keep kosher while he was on the road, subsisting on hard boiled eggs and sardines. While his business flourished in the 1920s, it failed during the Great Depression. He later opened a scrapyard in Knoxville, but died tragically in 1939, after which his wife Ida ran the business. Her son-in-law, Buddy Cohen, soon took over the business and guided it through the boom years of the 1940s and 50s. Glazer Iron and Steel became very successful and the Glazer/Cohen family became one of the wealthiest Jewish families in Knoxville.

Eastern European Jews in Knoxville followed the same path of upward mobility as the earlier German Jews had. Max Finklestein came to American from Poland in 1890, settling in Knoxville by 1895. He opened a clothing store which grew into a successful business, and later built the Finklestein Building in downtown Knoxville. Finklestein served as president of Heska Amuna and the local chapter of B’nai B’rith, and was also involved in several non-Jewish fraternal societies.

The path to success was not always short or easy. Oscar Glazer came to the U.S. from Russia before World War I, settling in Atlanta. After the lynching of Leo Frank, Glazer left Atlanta and moved to Knoxville, where he opened a small grocery store. The business closed in 1916 after Glazer’s bank failed. When America entered World War I, Glazer traveled the region buying scrap metal, which had become a hot commodity. Glazer managed to keep kosher while he was on the road, subsisting on hard boiled eggs and sardines. While his business flourished in the 1920s, it failed during the Great Depression. He later opened a scrapyard in Knoxville, but died tragically in 1939, after which his wife Ida ran the business. Her son-in-law, Buddy Cohen, soon took over the business and guided it through the boom years of the 1940s and 50s. Glazer Iron and Steel became very successful and the Glazer/Cohen family became one of the wealthiest Jewish families in Knoxville.

Eastern European Jews in Knoxville

Eastern European Jews in Knoxville followed the same path of upward mobility as the earlier German Jews had. Max Finklestein came to American from Poland in 1890, settling in Knoxville by 1895. He opened a clothing store which grew into a successful business, and later built the Finklestein Building in downtown Knoxville. Finklestein served as president of Heska Amuna and the local chapter of B’nai B’rith, and was also involved in several non-Jewish fraternal societies.

The path to success was not always short or easy. Oscar Glazer came to the U.S. from Russia before World War I, settling in Atlanta. After the lynching of Leo Frank, Glazer left Atlanta and moved to Knoxville, where he opened a small grocery store. The business closed in 1916 after Glazer’s bank failed. When America entered World War I, Glazer traveled the region buying scrap metal, which had become a hot commodity. Glazer managed to keep kosher while he was on the road, subsisting on hard boiled eggs and sardines. While his business flourished in the 1920s, it failed during the Great Depression. He later opened a scrapyard in Knoxville, but died tragically in 1939, after which his wife Ida ran the business. Her son-in-law, Buddy Cohen, soon took over the business and guided it through the boom years of the 1940s and 50s. Glazer Iron and Steel became very successful and the Glazer/Cohen family became one of the wealthiest Jewish families in Knoxville.

Eastern European Jews in Knoxville followed the same path of upward mobility as the earlier German Jews had. Max Finklestein came to American from Poland in 1890, settling in Knoxville by 1895. He opened a clothing store which grew into a successful business, and later built the Finklestein Building in downtown Knoxville. Finklestein served as president of Heska Amuna and the local chapter of B’nai B’rith, and was also involved in several non-Jewish fraternal societies.

The path to success was not always short or easy. Oscar Glazer came to the U.S. from Russia before World War I, settling in Atlanta. After the lynching of Leo Frank, Glazer left Atlanta and moved to Knoxville, where he opened a small grocery store. The business closed in 1916 after Glazer’s bank failed. When America entered World War I, Glazer traveled the region buying scrap metal, which had become a hot commodity. Glazer managed to keep kosher while he was on the road, subsisting on hard boiled eggs and sardines. While his business flourished in the 1920s, it failed during the Great Depression. He later opened a scrapyard in Knoxville, but died tragically in 1939, after which his wife Ida ran the business. Her son-in-law, Buddy Cohen, soon took over the business and guided it through the boom years of the 1940s and 50s. Glazer Iron and Steel became very successful and the Glazer/Cohen family became one of the wealthiest Jewish families in Knoxville.

Civic Engagement

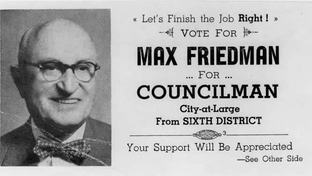

From their role as merchants, a number of Knoxville Jews became active in local civic and political affairs. Frank Winick, the son of Rabbi Isaac Winick, was a close political ally of Mayor George Dempster, and served as justice of the peace. Charles Siegal served on the Knoxville City Council and spent time as vice-mayor. Max Wolf was a longtime county commissioner. Perhaps the most influential of these Jewish politicos was Max Friedman, who had come to the U.S. from Russia as a teenager. Friedman owned a big jewelry store in downtown Knoxville, but his real passion was politics and the Democratic Party. According to local legend, Friedman was visiting with Franklin Roosevelt as he was first running for president in 1932. When FDR mentioned his lack of a good campaign slogan, Friedman reportedly suggested “a New Deal.” Friedman later served on the Knoxville City Council for twenty years, as well as the county court and election commission. During the 1960s, David Blumberg was a progressive voice on the Knoxville City Council, fighting against the White Citizen’s Council. In 1971, Blumberg was elected the international president of B’nai B’rith.

Knoxville Jews were also engaged in Jewish causes like Zionism. They founded the Ohavei Zion Society in 1900, which later evolved into the Knoxville Zionist District. Gert Weinstein founded a local chapter of Hadassah in the late 1920s. Most Knoxville Zionists belonged to the Orthodox congregation Heska Amuna, although some Beth El members were also active in the local movement. Several Knoxville Jews became leaders of national Zionist organizations. Ben Winick was the regional president of the Zionist Organization of America in 1951, while Mrs. J.B. Corkland was a regional president of Hadassah. Sam Rosen and his wife Esther were ardent Zionists who donated lots of money during Israel Bond Drives. In 1953, Sam was a delegate at the founding meeting of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), which lobbies the U.S. government to support the Jewish state. In 1951, Israel’s first Prime Minister, David Ben Gurion, came to Knoxville to tour the facilities of the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA). Knoxville Jews held a large formal dinner in his honor at the Farragut Hotel. During the 1967 War, Jews in Knoxville raised $67,000 in one day to support the besieged Jewish state, with several local Gentiles contributing to the cause.

From their role as merchants, a number of Knoxville Jews became active in local civic and political affairs. Frank Winick, the son of Rabbi Isaac Winick, was a close political ally of Mayor George Dempster, and served as justice of the peace. Charles Siegal served on the Knoxville City Council and spent time as vice-mayor. Max Wolf was a longtime county commissioner. Perhaps the most influential of these Jewish politicos was Max Friedman, who had come to the U.S. from Russia as a teenager. Friedman owned a big jewelry store in downtown Knoxville, but his real passion was politics and the Democratic Party. According to local legend, Friedman was visiting with Franklin Roosevelt as he was first running for president in 1932. When FDR mentioned his lack of a good campaign slogan, Friedman reportedly suggested “a New Deal.” Friedman later served on the Knoxville City Council for twenty years, as well as the county court and election commission. During the 1960s, David Blumberg was a progressive voice on the Knoxville City Council, fighting against the White Citizen’s Council. In 1971, Blumberg was elected the international president of B’nai B’rith.

Knoxville Jews were also engaged in Jewish causes like Zionism. They founded the Ohavei Zion Society in 1900, which later evolved into the Knoxville Zionist District. Gert Weinstein founded a local chapter of Hadassah in the late 1920s. Most Knoxville Zionists belonged to the Orthodox congregation Heska Amuna, although some Beth El members were also active in the local movement. Several Knoxville Jews became leaders of national Zionist organizations. Ben Winick was the regional president of the Zionist Organization of America in 1951, while Mrs. J.B. Corkland was a regional president of Hadassah. Sam Rosen and his wife Esther were ardent Zionists who donated lots of money during Israel Bond Drives. In 1953, Sam was a delegate at the founding meeting of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), which lobbies the U.S. government to support the Jewish state. In 1951, Israel’s first Prime Minister, David Ben Gurion, came to Knoxville to tour the facilities of the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA). Knoxville Jews held a large formal dinner in his honor at the Farragut Hotel. During the 1967 War, Jews in Knoxville raised $67,000 in one day to support the besieged Jewish state, with several local Gentiles contributing to the cause.

Congregations in the Mid and Late 20th Century

Knoxville Jews continued to support their congregations in the mid and late 20th century. Beth El’s membership grew tremendously in the post-war years, from 45 members in 1940 to 150 in 1962. This growth prompted the congregation to build a bigger synagogue in 1957. Beth El followed many of its members by moving out to the suburbs of west Knoxville. Soon, both the JCC and Heska Amuna followed. The Arnstein family were the major benefactors of Beth El’s new synagogue on Kingston Pike Road, which was designed by temple member Sam Good. In 1993, the building was expanded and renovated, as the congregation had grown to well over 200 families. Today, Beth El has 240 member families.

Heska Amuna has grown as well, remaining somewhat larger than Beth El. In 1957, it had 204 members, as compared to 120 at Beth El. In 1960, it built a new synagogue on Kingston Pike Road, just down the street from Beth El’s new temple. That same year, the congregation voted to join the Conservative movement, officially leaving Orthodox Judaism behind, after having long ago introduced such changes as mixed-gender seating and confirmation. Over the years, Heska Amuna has had several rabbis, with none staying in Knoxville for very long. Rabbi Max Zucker, who led the congregation from 1960 to 1969, has been its longest serving rabbi since Issac Winick in the early 20th century. The congregation now numbers 250 member families.

Knoxville Jews continued to support their congregations in the mid and late 20th century. Beth El’s membership grew tremendously in the post-war years, from 45 members in 1940 to 150 in 1962. This growth prompted the congregation to build a bigger synagogue in 1957. Beth El followed many of its members by moving out to the suburbs of west Knoxville. Soon, both the JCC and Heska Amuna followed. The Arnstein family were the major benefactors of Beth El’s new synagogue on Kingston Pike Road, which was designed by temple member Sam Good. In 1993, the building was expanded and renovated, as the congregation had grown to well over 200 families. Today, Beth El has 240 member families.

Heska Amuna has grown as well, remaining somewhat larger than Beth El. In 1957, it had 204 members, as compared to 120 at Beth El. In 1960, it built a new synagogue on Kingston Pike Road, just down the street from Beth El’s new temple. That same year, the congregation voted to join the Conservative movement, officially leaving Orthodox Judaism behind, after having long ago introduced such changes as mixed-gender seating and confirmation. Over the years, Heska Amuna has had several rabbis, with none staying in Knoxville for very long. Rabbi Max Zucker, who led the congregation from 1960 to 1969, has been its longest serving rabbi since Issac Winick in the early 20th century. The congregation now numbers 250 member families.

Morristown

Jews in small towns around East Tennessee were part of Knoxville’s extended Jewish community. Morristown, located 50 miles northeast of Knoxville, emerged as a manufacturing center after World War II. A handful of Jewish furniture manufacturers from the North moved to Morristown in the 1950s and 60s to take advantage of its cheap, non-union labor. These Jewish owners came to dominate the furniture manufacturing business in Morristown. The group had to decide whether to form their own congregation, or join the ones in Knoxville. Most chose to join Temple Beth El, and would drive to Knoxville for Shabbat services and Sunday school. Beth El’s rabbi would travel to Morristown once a month to lead services. Morristown Jews played a leading role in the fundraising campaign to build a new temple for Beth El in 1957. By the late 1960s, Morristown had a significant Jewish population; 25 members of the Knoxville Hadassah chapter lived in Morristown. In the 1970s, its Jewish community went into decline, and few Jews still live there today.

Jews in small towns around East Tennessee were part of Knoxville’s extended Jewish community. Morristown, located 50 miles northeast of Knoxville, emerged as a manufacturing center after World War II. A handful of Jewish furniture manufacturers from the North moved to Morristown in the 1950s and 60s to take advantage of its cheap, non-union labor. These Jewish owners came to dominate the furniture manufacturing business in Morristown. The group had to decide whether to form their own congregation, or join the ones in Knoxville. Most chose to join Temple Beth El, and would drive to Knoxville for Shabbat services and Sunday school. Beth El’s rabbi would travel to Morristown once a month to lead services. Morristown Jews played a leading role in the fundraising campaign to build a new temple for Beth El in 1957. By the late 1960s, Morristown had a significant Jewish population; 25 members of the Knoxville Hadassah chapter lived in Morristown. In the 1970s, its Jewish community went into decline, and few Jews still live there today.

A Community Renaissance

While Morristown has declined, Knoxville has experienced a Jewish renaissance. The city’s Jewish population has grown from 766 Jews in 1948 to an estimated 1,800 today. Hidden within this growth is a significant demographic shift within Knoxville’s Jewish community. For a long time, most Knoxville Jews were merchants, and Jewish-owned clothing, hardware, and jewelry stores once lined downtown Knoxville. Harold’s Deli served kosher (and nonkosher) meat downtown for over 60 years. As late as 1971, merchant families still constituted about two-thirds of the Jewish community. But over the past few decades, most all of these stores have closed, as these retiring Jewish merchants were offset by increasing numbers of Jewish professionals moving to Knoxville to work in its growing medical center, the Tennessee Valley Authority, or the science labs at nearby Oak Ridge.

While Morristown has declined, Knoxville has experienced a Jewish renaissance. The city’s Jewish population has grown from 766 Jews in 1948 to an estimated 1,800 today. Hidden within this growth is a significant demographic shift within Knoxville’s Jewish community. For a long time, most Knoxville Jews were merchants, and Jewish-owned clothing, hardware, and jewelry stores once lined downtown Knoxville. Harold’s Deli served kosher (and nonkosher) meat downtown for over 60 years. As late as 1971, merchant families still constituted about two-thirds of the Jewish community. But over the past few decades, most all of these stores have closed, as these retiring Jewish merchants were offset by increasing numbers of Jewish professionals moving to Knoxville to work in its growing medical center, the Tennessee Valley Authority, or the science labs at nearby Oak Ridge.

The Jewish Community in Knoxville Today

Over the past few decades, Knoxville’s Jewish community has evolved from a close-knit group of merchant families bound by kinship ties, to a collection of unrelated professionals, often from other parts of the country. The native Knoxville Jew has become a rather rare breed. Today, the community is overwhelmingly professional. According to historian Wendy Besmann, 95% of working Jewish families are professionals. In this sense, Knoxville has been a microcosm of the demographic changes that have swept through the Jewish South over the last several decades. While these changes have decimated many small Jewish communities across the South, Knoxville has thrived as it has become an educational, medical, and research hub.

Knoxville has always been a strong Jewish community despite its small size. With fewer than 800 Jews in 1948, Knoxville supported two congregations, a JCC, and a Jewish Federation. As the size of the Jewish community has grown over the last half century, so have its activity and its future prospects.

Knoxville has always been a strong Jewish community despite its small size. With fewer than 800 Jews in 1948, Knoxville supported two congregations, a JCC, and a Jewish Federation. As the size of the Jewish community has grown over the last half century, so have its activity and its future prospects.

Sources

Besmann,Wendy Lowe. A Separate Circle: Jewish Life in Knoxville, Tennessee. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2001.