Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Union City, Tennessee

Union City: Historical Overview

In her memoir The Jew Store, Stella Suberman tells the story of her family’s time living in “Concordia, Tennessee” in the 1920s. Concordia was a pseudonym for Union City, a town in the northwest corner of the state. Her family owned Kaufman’s Low Price Store, which was located in downtown Union City in the 1920s. Suberman’s family did not stay in Union City very long. As one of the only Jewish families in town, they moved back East once their older children began to date local Gentiles. Suberman’s parents found the social acceptance they enjoyed in Union City more of a threat than anti-Semitism. This story may have turned out differently if it had taken place after World War II, when several Jewish families moved to the area and created a strong, close-knit community.

Located on the New Madrid fault line, the area around Union City in Obion County was reshaped during an 1811 earthquake, in which the Mississippi River ran backwards for several hours and created Reelfoot Lake, a 23-mile long swamp. The newly formed lake displaced Cherokee hunting grounds and opened the way for American settlement in the area. One of the earliest white settlers was Davey Crockett, who was elected to the state legislature from neighboring Weakley County in 1823. Union City was incorporated in 1861; its name honored the origins of the town, which arose upon the confluence of two railroad lines. After the Civil War and Reconstruction, Union City emerged as an industrial center during the era of the “New South.” Between 1875 and 1879, three furniture factories opened in the area, as Union City became a typical “boom town.” Along with a fast-growing population, Union City also experienced all the vices usually associated with boomtowns, including several saloons.

It was during this boom era that Jews first arrived in Union City, forming the foundation for a community that lasted through the end of the 20th century.

Located on the New Madrid fault line, the area around Union City in Obion County was reshaped during an 1811 earthquake, in which the Mississippi River ran backwards for several hours and created Reelfoot Lake, a 23-mile long swamp. The newly formed lake displaced Cherokee hunting grounds and opened the way for American settlement in the area. One of the earliest white settlers was Davey Crockett, who was elected to the state legislature from neighboring Weakley County in 1823. Union City was incorporated in 1861; its name honored the origins of the town, which arose upon the confluence of two railroad lines. After the Civil War and Reconstruction, Union City emerged as an industrial center during the era of the “New South.” Between 1875 and 1879, three furniture factories opened in the area, as Union City became a typical “boom town.” Along with a fast-growing population, Union City also experienced all the vices usually associated with boomtowns, including several saloons.

It was during this boom era that Jews first arrived in Union City, forming the foundation for a community that lasted through the end of the 20th century.

Stories of the Jewish Community in Union City

Early Jewish Residents

David Lowenheim came to town in 1882 and opened a dry goods store that catered to the growing number of factory workers. David Levy was a successful tailor who arrived the same year as Lowenheim. Levy gained notice by penning theater reviews of traveling shows that came through Union City for the New York Mirror newspaper. Both Levy and Lowenheim failed to sink deep roots into the community and moved away once the industrial boom petered out in the 1890s. For the next few decades, a handful of Jewish merchants lived in Union City for brief periods of time before moving on. In 1894, Julius Falkoff married Celia Klibausky in Union City, the first Jewish wedding in the town. The Falkoffs soon moved to Memphis, and then opened a store in East Prairie, Missouri.

The Jewish history of Obion County was transformed when Solomon Shatz, a Russian immigrant, bought a dry goods store in the small town of Kenton and moved his large family from Jackson, Tennessee. Sol Shatz and his children became major economic forces in the area for much of the 20th century. They bought lots of property in the county, and opened Kenton’s first cotton gin. The Shatz family was also involved in the egg and poultry business. Sol’s sons opened retail stores in towns throughout the area. Dave Shatz opened a branch of the Shatz Brothers store in Union City in 1918; it remained in business for over 50 years. Sam Shatz helped to make strawberries a cash crop for Obion County, and became a major wholesale supplier of the fruit. Sam was very respected in the community, and was often asked to mediate major disputes in town. In one case, he settled a factional dispute within a local church. Various Shatzes served on local bank boards. Dave Shatz became an important figure in the economic development of Union City. He helped to bring industry to the area, often investing in ventures that would benefit the local economy. Popularly known as “Uncle Dave,” Shatz served on the city council and was head of the local chamber of commerce.

The success of the Shatzes also benefited the local Jewish community. Several Jews moved to Union City towork for the family’s businesses. Sam Byer of Jackson, Tennessee, married Sadie Shatz and went to work with her brothers. Max Altfeld came in the 1930s to work for the family. Descendants of the Shatz brothers owned businesses in Union City well into the 1970s. Many of the Jews in Obion County not named Shatz had economic connections with the family.

David Lowenheim came to town in 1882 and opened a dry goods store that catered to the growing number of factory workers. David Levy was a successful tailor who arrived the same year as Lowenheim. Levy gained notice by penning theater reviews of traveling shows that came through Union City for the New York Mirror newspaper. Both Levy and Lowenheim failed to sink deep roots into the community and moved away once the industrial boom petered out in the 1890s. For the next few decades, a handful of Jewish merchants lived in Union City for brief periods of time before moving on. In 1894, Julius Falkoff married Celia Klibausky in Union City, the first Jewish wedding in the town. The Falkoffs soon moved to Memphis, and then opened a store in East Prairie, Missouri.

The Jewish history of Obion County was transformed when Solomon Shatz, a Russian immigrant, bought a dry goods store in the small town of Kenton and moved his large family from Jackson, Tennessee. Sol Shatz and his children became major economic forces in the area for much of the 20th century. They bought lots of property in the county, and opened Kenton’s first cotton gin. The Shatz family was also involved in the egg and poultry business. Sol’s sons opened retail stores in towns throughout the area. Dave Shatz opened a branch of the Shatz Brothers store in Union City in 1918; it remained in business for over 50 years. Sam Shatz helped to make strawberries a cash crop for Obion County, and became a major wholesale supplier of the fruit. Sam was very respected in the community, and was often asked to mediate major disputes in town. In one case, he settled a factional dispute within a local church. Various Shatzes served on local bank boards. Dave Shatz became an important figure in the economic development of Union City. He helped to bring industry to the area, often investing in ventures that would benefit the local economy. Popularly known as “Uncle Dave,” Shatz served on the city council and was head of the local chamber of commerce.

The success of the Shatzes also benefited the local Jewish community. Several Jews moved to Union City towork for the family’s businesses. Sam Byer of Jackson, Tennessee, married Sadie Shatz and went to work with her brothers. Max Altfeld came in the 1930s to work for the family. Descendants of the Shatz brothers owned businesses in Union City well into the 1970s. Many of the Jews in Obion County not named Shatz had economic connections with the family.

An Industrial Boom

After World War II, Union City experienced another industrial boom, which finally led to the creation of an organized Jewish community. While cotton and corn farming remained important economic staples in the area, several companies built factories in and around Union City in the 1950s. The Brown Shoe Company led the way, though the opening of a Goodyear Tire plant in the early 1970s marked the height of the boom. In 2007, Goodyear was still the largest employer in Union City.

Several Jews took part in Obion County’s version of the industrial revolution. Phil and Nettie Roseman moved from New York and opened garment factories around Union City. David and Sylvia Wechsler opened a uniform factory in nearby Martin. Irving Berlin also opened a factory in the area. All of these new residents chose to live in Union City, where the county’s Jewish community was centered. Other Jews moved to town to open retail stores in the wake of the area’s economic growth. Harry and Ruth Gorman came to town from Nashville in 1950 after he received a job offer as the manager of an upscale women's store.

The Gormans’ experience moving to Union City in 1950 reflected the nature of the local Jewish community. Soon after they arrived in town, they began receiving calls from local Jews inviting them to social events. Since there was no congregation or synagogue, the Jewish community of Union City was largely constituted through social ties. Union City Jews socialized together, hosting dinner parties and card playing sessions with each other. Six Jewish families lived on the same block on Bishop Street, in a subdivision that had been developed by Dave Shatz. Interestingly, they were able to build a strong Jewish community with no religious foundation. It wasn’t because they were irreligious; Union City Jews usually belonged to congregations in nearby cities like Paducah, Kentucky, Jackson, Tennessee, and Cairo, Illinois. For their first few years in Union City, the Gormans ordered kosher meat from Memphis. They had observed the Jewish dietary laws in Nashville, but found this to be a challenge in Union City. After a few years, they dispensed with the inconvenience of ordering kosher meat, and adjusted their eating habits to the local fare.

After World War II, Union City experienced another industrial boom, which finally led to the creation of an organized Jewish community. While cotton and corn farming remained important economic staples in the area, several companies built factories in and around Union City in the 1950s. The Brown Shoe Company led the way, though the opening of a Goodyear Tire plant in the early 1970s marked the height of the boom. In 2007, Goodyear was still the largest employer in Union City.

Several Jews took part in Obion County’s version of the industrial revolution. Phil and Nettie Roseman moved from New York and opened garment factories around Union City. David and Sylvia Wechsler opened a uniform factory in nearby Martin. Irving Berlin also opened a factory in the area. All of these new residents chose to live in Union City, where the county’s Jewish community was centered. Other Jews moved to town to open retail stores in the wake of the area’s economic growth. Harry and Ruth Gorman came to town from Nashville in 1950 after he received a job offer as the manager of an upscale women's store.

The Gormans’ experience moving to Union City in 1950 reflected the nature of the local Jewish community. Soon after they arrived in town, they began receiving calls from local Jews inviting them to social events. Since there was no congregation or synagogue, the Jewish community of Union City was largely constituted through social ties. Union City Jews socialized together, hosting dinner parties and card playing sessions with each other. Six Jewish families lived on the same block on Bishop Street, in a subdivision that had been developed by Dave Shatz. Interestingly, they were able to build a strong Jewish community with no religious foundation. It wasn’t because they were irreligious; Union City Jews usually belonged to congregations in nearby cities like Paducah, Kentucky, Jackson, Tennessee, and Cairo, Illinois. For their first few years in Union City, the Gormans ordered kosher meat from Memphis. They had observed the Jewish dietary laws in Nashville, but found this to be a challenge in Union City. After a few years, they dispensed with the inconvenience of ordering kosher meat, and adjusted their eating habits to the local fare.

Organized Jewish Life in Union City

The growing number of Jewish children in Union City eventually led the community to organize a congregation. In the 1930s and 1940s, there were a few short-lived efforts to form a religious school for their children. Most Jews in Union City sent their children to other cities for Sunday school. In 1954, they formally established a religious school in Union City with parents serving as the teachers. The school first met at the Davey Crockett Hotel, and later in the Masonic Lodge and a local Baptist Church. The children would regularly travel to Jackson for special holiday programs.It was during one of these trips that a tragedy struck the group, which prompted them to build a permanent home for Union City’s Jewish community.

On March 10, 1957, heading back from Jackson after a Purim party, several Union City children were in a car accident. The driver lost control and the car overturned. Five-year-old Sammy Shatz, the son of Mark and Gladys (Waldman) Shatz, was thrown from the car and died. The other children in the car were injured. After the accident, local Jews resolved to keep their children closer to home and decided to build a Jewish center for Union City. Dave Shatz donated a piece of land, and the “Jewish Center” was dedicated in 1959.

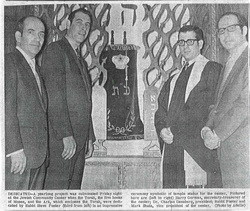

According to its charter, the Jewish Center was to be used as a religious, educational, and social facility for the area’s Jews. In most communities, Jews organized a congregation first, and then built or acquired a building. In Union City, it was the opposite; the building inspired the creation of a religious congregation. At first, the Jewish Center was used primarily for Sunday school and social gatherings. Union City Jews would still travel to other cities for religious services. The raised platform at one end of the building was used as a stage, not a bimah. In 1963, Union City Jews requested a student rabbi from Hebrew Union College to help run the religious school and prepare older students for confirmation. This led to a string of student rabbis, who were able to gently coax the “Jewish Center” into a religious congregation. By the late 1960s, under the guidance of student rabbi Steven Foster, the group had acquired a Torah, and built an ark to house it, transforming the stage into a bimah. Student rabbis, who started out coming once a month, began to come once a fortnight. By 1970, regular Shabbat and High Holiday services were being held at the Jewish Center. Although the community now had a functioning religious institution that was affiliated with the national Reform Movement, they continued to identify the congregation with the name of the building, “the Jewish Center.”

The growing number of Jewish children in Union City eventually led the community to organize a congregation. In the 1930s and 1940s, there were a few short-lived efforts to form a religious school for their children. Most Jews in Union City sent their children to other cities for Sunday school. In 1954, they formally established a religious school in Union City with parents serving as the teachers. The school first met at the Davey Crockett Hotel, and later in the Masonic Lodge and a local Baptist Church. The children would regularly travel to Jackson for special holiday programs.It was during one of these trips that a tragedy struck the group, which prompted them to build a permanent home for Union City’s Jewish community.

On March 10, 1957, heading back from Jackson after a Purim party, several Union City children were in a car accident. The driver lost control and the car overturned. Five-year-old Sammy Shatz, the son of Mark and Gladys (Waldman) Shatz, was thrown from the car and died. The other children in the car were injured. After the accident, local Jews resolved to keep their children closer to home and decided to build a Jewish center for Union City. Dave Shatz donated a piece of land, and the “Jewish Center” was dedicated in 1959.

According to its charter, the Jewish Center was to be used as a religious, educational, and social facility for the area’s Jews. In most communities, Jews organized a congregation first, and then built or acquired a building. In Union City, it was the opposite; the building inspired the creation of a religious congregation. At first, the Jewish Center was used primarily for Sunday school and social gatherings. Union City Jews would still travel to other cities for religious services. The raised platform at one end of the building was used as a stage, not a bimah. In 1963, Union City Jews requested a student rabbi from Hebrew Union College to help run the religious school and prepare older students for confirmation. This led to a string of student rabbis, who were able to gently coax the “Jewish Center” into a religious congregation. By the late 1960s, under the guidance of student rabbi Steven Foster, the group had acquired a Torah, and built an ark to house it, transforming the stage into a bimah. Student rabbis, who started out coming once a month, began to come once a fortnight. By 1970, regular Shabbat and High Holiday services were being held at the Jewish Center. Although the community now had a functioning religious institution that was affiliated with the national Reform Movement, they continued to identify the congregation with the name of the building, “the Jewish Center.”

The evolution of the Jewish Center provoked some controversy amongst its members. In the late 1960s, some members objected to holding weekly bridge club meetings at the center. The room the card players had been using was now an unambiguous sanctuary, and some thought it was inappropriate. When the board voted narrowly to ban the card playing, some members resigned in protest, though this rift was eventually healed.

In the early 1970s, the congregation had about 15 to 20 children, who were involved with SOFTY, the regional Jewish youth organization, and the newly founded Henry S. Jacobs Camp in Utica, Mississippi. The Jewish Center was a regional congregation, attracting Jews from surrounding towns in Tennessee and Kentucky. During the Yom Kippur War of 1973, congregation members raised $20,000 for Israel. That next year, their student rabbi wrote a history of the local Jewish community and predicted that the congregation would double in size over the next 25 years due to the increasing industrial development in town.

Unfortunately, this growth never occurred, and the community has slowly shrunk since the 1970s. Most of the Jewish children raised in Union City didn’t return after college, moving instead to larger cities like Nashville and St. Louis. The string of Jewish-owned stores downtown gradually closed. Falkoff’s Department Store closed in the early 1990s, while Libby’s Store, owned by the Gormans, closed later that decade. Today, there are no Jewish-owned retail stores in Union City.

In the early 1970s, the congregation had about 15 to 20 children, who were involved with SOFTY, the regional Jewish youth organization, and the newly founded Henry S. Jacobs Camp in Utica, Mississippi. The Jewish Center was a regional congregation, attracting Jews from surrounding towns in Tennessee and Kentucky. During the Yom Kippur War of 1973, congregation members raised $20,000 for Israel. That next year, their student rabbi wrote a history of the local Jewish community and predicted that the congregation would double in size over the next 25 years due to the increasing industrial development in town.

Unfortunately, this growth never occurred, and the community has slowly shrunk since the 1970s. Most of the Jewish children raised in Union City didn’t return after college, moving instead to larger cities like Nashville and St. Louis. The string of Jewish-owned stores downtown gradually closed. Falkoff’s Department Store closed in the early 1990s, while Libby’s Store, owned by the Gormans, closed later that decade. Today, there are no Jewish-owned retail stores in Union City.

The Jewish Community in Union City Today

The Jewish Center stopped hosting student rabbis sometime in the 1990s, and by 2004 had disbanded. On October 6, 2012, the Union City Jewish Center was dismantled. The Star of David window, their Torah, memorial boards and plaques, two standup menorah lights, the contents of their library, their ark and ner tamid (eternal light), their stand up podium, the large cast iron letters that made up their external sign, and other objects have become a part of Jackson's Congregation B'nai Israel's permanent historical display. A unification service was held December 5, 2014, at Congregation B'nai Israel honoring the Union Congregation and dedicating their Torah.