Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Chattanooga, Tennessee

Chattanooga: Historical Overview

|

Chattanooga sits in a bend of the Tennessee River, at a point where the ridges and valleys of the Appalachian Mountains flatten out into the Cumberland Plateau. The city’s location at this strategic geographic crossroads bestowed equal parts of good fortune and misery upon its residents, and the area bore witness to many of the nation’s great tragedies and triumphs.

The Cherokee Indians moved into the area in the late 1700s, and by the early 1800s built a settlement named Ross’s Landing. Following the passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, Ross’s Landing served as one of the three primary “emigration depots,” where members of the Cherokee Nation were assembled prior to their forced march westward along the Trail of Tears. Rail transportation came to Chattanooga in the 1850s, and in the following decades the city emerged as a major transportation hub between the South, the Midwest and the Eastern Seaboard. Goods and travelers poured through the town, and large railroad yards grew to support the burgeoning traffic. But Chattanooga’s increasing prominence also rendered it a tactical priority for both the Union and Confederate armies soon after the commencement of hostilities. The opposing forces fought a number of battles for control of the town and the surrounding heights before the city finally fell into Union hands following General Grant’s victory in the Third Battle of Chattanooga in November of 1863. Although there is some record of Jewish settlement in Chattanooga prior to the Civil War, the beginnings of the first Jewish community appeared in Chattanooga in the years after. From these settlers, a vital community grew and lasts today. |

Stories of the Jewish Community in Chattanooga

Early Organized Jewish Life

Immigrants Fannie Schwartzenberg Bach and Jacob Bach arrived in Chattanooga in the 1860s from their home in Germany. The Bachs began holding services in their home in 1866, primarily for the Jewish soldiers who remained in Chattanooga following the conclusion of the war. Jacob Bach served as the congregation’s first lay rabbi, cantor, mohel, and shochet (kosher butcher).

In May of 1866, 21 young Jewish men organized a group named Chebra Gamilas Chaced, The Hebrew Benevolent Association, and received a formal state charter the following year. The group purchased a parcel of land for a cemetery at the corner of east Third and Collins Street for the sum of $225. In addition to providing a resting ground for Jewish community members, the association arranged for the bodies of Jewish soldiers fallen in the battles around Chattanooga to be exhumed and reburied in the new cemetery.

The fledgling congregation received a boost with the arrival of Rabbi E. K. Fischer in 1869. He served as a volunteer rabbi for the following two years, established a religious school, and oversaw the relocation of meetings to the Concordia Hall on Market Street. After Fischer stepped down in 1871 due to ill health, Dr. Marx Block assumed leadership of the congregation. Block, a druggist and wholesale merchant from Alsace-Lorraine, and his wife Delphine played a prominent role in early Chattanooga Jewish life. In 1877, Delphine organized the Hebrew Ladies Aid Society with a founding membership of 33 women.

Immigrants Fannie Schwartzenberg Bach and Jacob Bach arrived in Chattanooga in the 1860s from their home in Germany. The Bachs began holding services in their home in 1866, primarily for the Jewish soldiers who remained in Chattanooga following the conclusion of the war. Jacob Bach served as the congregation’s first lay rabbi, cantor, mohel, and shochet (kosher butcher).

In May of 1866, 21 young Jewish men organized a group named Chebra Gamilas Chaced, The Hebrew Benevolent Association, and received a formal state charter the following year. The group purchased a parcel of land for a cemetery at the corner of east Third and Collins Street for the sum of $225. In addition to providing a resting ground for Jewish community members, the association arranged for the bodies of Jewish soldiers fallen in the battles around Chattanooga to be exhumed and reburied in the new cemetery.

The fledgling congregation received a boost with the arrival of Rabbi E. K. Fischer in 1869. He served as a volunteer rabbi for the following two years, established a religious school, and oversaw the relocation of meetings to the Concordia Hall on Market Street. After Fischer stepped down in 1871 due to ill health, Dr. Marx Block assumed leadership of the congregation. Block, a druggist and wholesale merchant from Alsace-Lorraine, and his wife Delphine played a prominent role in early Chattanooga Jewish life. In 1877, Delphine organized the Hebrew Ladies Aid Society with a founding membership of 33 women.

Jewish Businesses in Chattanooga

Many of the leaders of the Hebrew Benevolent Association went into the retail business, and some realized substantial profits during the Civil War and subsequent Reconstruction. Morris Bradt, one of the group’s founding members, emigrated from Prussia and settled with his wife Julia in Chattanooga in the 1860s after spending some time in Pennsylvania. By the time of the 1870 census, he was a successful merchant and among the larger property owners in the town. Joseph Spitzer, another founding member and emigrant from Hungary, arrived in Chattanooga after living a number of years in Pennsylvania. In Chattanooga, he established a successful lumber dealership that thrived during the post-war rebuilding years. By 1870 he and his wife Babhetta presided over a large household that included their five children, a live-in servant, and three single Jewish boarders. The boarders had recently arrived in Chattanooga. Henry Deutsch, a 36 year-old silversmith from Germany, Samuel Geismar, a 27 year-old dry goods merchant from Baden, and George Schenk, a 27-year-old tailor from Prussia, lived with the Spitzer family.

Many of the leaders of the Hebrew Benevolent Association went into the retail business, and some realized substantial profits during the Civil War and subsequent Reconstruction. Morris Bradt, one of the group’s founding members, emigrated from Prussia and settled with his wife Julia in Chattanooga in the 1860s after spending some time in Pennsylvania. By the time of the 1870 census, he was a successful merchant and among the larger property owners in the town. Joseph Spitzer, another founding member and emigrant from Hungary, arrived in Chattanooga after living a number of years in Pennsylvania. In Chattanooga, he established a successful lumber dealership that thrived during the post-war rebuilding years. By 1870 he and his wife Babhetta presided over a large household that included their five children, a live-in servant, and three single Jewish boarders. The boarders had recently arrived in Chattanooga. Henry Deutsch, a 36 year-old silversmith from Germany, Samuel Geismar, a 27 year-old dry goods merchant from Baden, and George Schenk, a 27-year-old tailor from Prussia, lived with the Spitzer family.

Adolph Ochs

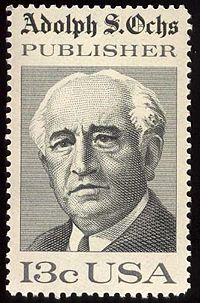

In 1878, 19-year-old Adolph Ochs borrowed $250 to purchase a controlling share in the Chattanooga Times, and ultimately built a newspaper publishing dynasty that extended far beyond Chattanooga and charted a new course for American journalism.

Ochs was born in 1858 to German immigrant parents Julius and Bertha Levy Ochs. The family lived in Cincinnati, but moved to Knoxville, Tennessee during the Civil War due to Bertha’s sympathies with the Confederacy. Julius supported the Union but even with their conflicting loyalties the family fared well in Tennessee, a border state where many residents harbored mixed allegiances. Adolph left school at a young age to work as a printer’s assistant at the Knoxville Chronicle and later at the Knoxville Tribune.

After purchasing his controlling interest in the struggling Chattanooga Times, Ochs rapidly restored the paper to solvency and success. Ochs ignored the common practice at the time of accepting payments to promote certain agendas or interests, instead declaring that “we shall conduct our business on business principles, neither seeking nor giving sops and donations." By 1880 Ochs was able to buy out the remaining half interest, and brought his father Julius and two brothers, George and Milton, to help with the paper.

Ochs earned national recognition for his success in Chattanooga, and in 1896 he assumed control of the heavily debt-ridden New York Times. Ochs immediately set about differentiating the Times from the “yellow journalism” rags predominant in the city. In contrast, Ochs advertised his paper as “clean, dignified, trustworthy and impartial,” and adopting the motto of “all the news that’s fit to print.” By his third year at the helm, the Times was profitable and expanded rapidly in subsequent decades.

Even after his triumph at the New York Times, Ochs continued to publish his Chattanooga paper, and contributed generously to the city. Ochs helped build Chattanooga’s public library, as well as roads, hospitals, public parks and an opera house. In 1883 he married Effie Miriam Wise, daughter of Hebrew Union College and Union of American Hebrew Congregations founder Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise.

In 1878, 19-year-old Adolph Ochs borrowed $250 to purchase a controlling share in the Chattanooga Times, and ultimately built a newspaper publishing dynasty that extended far beyond Chattanooga and charted a new course for American journalism.

Ochs was born in 1858 to German immigrant parents Julius and Bertha Levy Ochs. The family lived in Cincinnati, but moved to Knoxville, Tennessee during the Civil War due to Bertha’s sympathies with the Confederacy. Julius supported the Union but even with their conflicting loyalties the family fared well in Tennessee, a border state where many residents harbored mixed allegiances. Adolph left school at a young age to work as a printer’s assistant at the Knoxville Chronicle and later at the Knoxville Tribune.

After purchasing his controlling interest in the struggling Chattanooga Times, Ochs rapidly restored the paper to solvency and success. Ochs ignored the common practice at the time of accepting payments to promote certain agendas or interests, instead declaring that “we shall conduct our business on business principles, neither seeking nor giving sops and donations." By 1880 Ochs was able to buy out the remaining half interest, and brought his father Julius and two brothers, George and Milton, to help with the paper.

Ochs earned national recognition for his success in Chattanooga, and in 1896 he assumed control of the heavily debt-ridden New York Times. Ochs immediately set about differentiating the Times from the “yellow journalism” rags predominant in the city. In contrast, Ochs advertised his paper as “clean, dignified, trustworthy and impartial,” and adopting the motto of “all the news that’s fit to print.” By his third year at the helm, the Times was profitable and expanded rapidly in subsequent decades.

Even after his triumph at the New York Times, Ochs continued to publish his Chattanooga paper, and contributed generously to the city. Ochs helped build Chattanooga’s public library, as well as roads, hospitals, public parks and an opera house. In 1883 he married Effie Miriam Wise, daughter of Hebrew Union College and Union of American Hebrew Congregations founder Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise.

A Reform Congregation

The Hebrew Benevolent Association officially affiliated with the Union of American Hebrew Congregations the same year Ochs married. In 1888, Harry Wise Sr., a son of Isaac Wise, also moved to Chattanooga, further cementing ties between the Chattanooga congregation and the Reform movement.

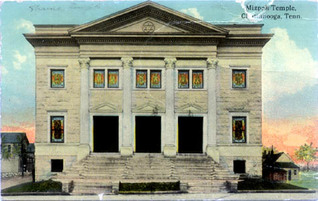

The congregation’s first temple, built in 1882, occupied a lot on Walnut Street near Fifth. The group formally adopted the name of “Mitzpah” (soon dropping the “t” to become “Mizpah”) in 1888. The Hebrew word “Mitzpah” literally translates to “overlook” or “lookout” and most likely refers to Lookout Mountain or the other elevations around Chattanooga. In 1904, they built a new synagogue on the corner of Lindsay and Oak Streets, which served the congregation for the next 24 years.

The Community Grows

Beginning in the 1880s, increasing numbers of Jewish arrivals from Eastern Europe began to settle in the area, carrying with them aspirations for a better life and traditional Jewish beliefs. In 1880, twenty-eight-year-old Wolfe Brody and his wife Dora brought their family to Chattanooga from Poland, and encouraged others to settle in the city. Brody opened a clothing retail business, grew successful, and others soon followed his lead. Dora built the city’s first mikvah, or ritual bath, by digging a pit in her backyard and putting a wooden box inside. She also provided board for the numerous itinerant peddlers who returned to the city for the Sabbath and holidays.

Business networking brought a growing number of Eastern European Jews to Chattanooga. In the late 1880s, brothers Halman and Rueben Blumberg settled in Chattanooga and established a peddler supply business. The Blumbergs regularly traveled to New York to recruit new peddlers and ended up bringing approximately 40 immigrants to the Chattanooga area. The Blumbergs paid the railroad fare from New York, supplied the peddlers with merchandise, and assisted them in establishing routes. By 1918, approximately 1,400 Jews lived in Chattanooga.

The Hebrew Benevolent Association officially affiliated with the Union of American Hebrew Congregations the same year Ochs married. In 1888, Harry Wise Sr., a son of Isaac Wise, also moved to Chattanooga, further cementing ties between the Chattanooga congregation and the Reform movement.

The congregation’s first temple, built in 1882, occupied a lot on Walnut Street near Fifth. The group formally adopted the name of “Mitzpah” (soon dropping the “t” to become “Mizpah”) in 1888. The Hebrew word “Mitzpah” literally translates to “overlook” or “lookout” and most likely refers to Lookout Mountain or the other elevations around Chattanooga. In 1904, they built a new synagogue on the corner of Lindsay and Oak Streets, which served the congregation for the next 24 years.

The Community Grows

Beginning in the 1880s, increasing numbers of Jewish arrivals from Eastern Europe began to settle in the area, carrying with them aspirations for a better life and traditional Jewish beliefs. In 1880, twenty-eight-year-old Wolfe Brody and his wife Dora brought their family to Chattanooga from Poland, and encouraged others to settle in the city. Brody opened a clothing retail business, grew successful, and others soon followed his lead. Dora built the city’s first mikvah, or ritual bath, by digging a pit in her backyard and putting a wooden box inside. She also provided board for the numerous itinerant peddlers who returned to the city for the Sabbath and holidays.

Business networking brought a growing number of Eastern European Jews to Chattanooga. In the late 1880s, brothers Halman and Rueben Blumberg settled in Chattanooga and established a peddler supply business. The Blumbergs regularly traveled to New York to recruit new peddlers and ended up bringing approximately 40 immigrants to the Chattanooga area. The Blumbergs paid the railroad fare from New York, supplied the peddlers with merchandise, and assisted them in establishing routes. By 1918, approximately 1,400 Jews lived in Chattanooga.

Orthodox Congregations in Chattanooga

Wolfe and Dora Brody initially held Orthodox services at their home, and the peddlers and merchants returned from outlying areas every Friday to observe the Sabbath with the community. The group formally adopted the name of B’nai Zion in 1888 and rented a succession of halls and buildings for services. Mr. J. Friedman conducted services and also served as cantor and shochet. For a number of years the congregation rented a building at 1027 Carter Street which was destroyed by fire in the 1890s. One of the congregants, L. Slabosky, rushed into the roaring flames to save the Torah scrolls. He escaped from the building with the salvaged scrolls, but soon collapsed from the smoke and the heat and never fully recovered from the fire. The congregation bought land for a cemetery in 1890 after Mizpah Congregation stopped accepting non-member burials. By 1902 many of the members were financially stable, and contributed funds to build a large Romanesque synagogue at the corner of Fourteenth and Carter streets. Despite his own ties to the Reform congregation, Adolph Ochs assisted their efforts with a large contribution.

During this period, a second Orthodox congregation formed in the city. In 1904, a small group began meeting in a rented space on Poplar Street, before moving into a building shared with the Workman’s Circle. The congregation, Shaari-Zion, persisted for approximately 40 years, many of them under the leadership of lay Rabbi Herschel Contor. In addition to his role at Shaari Zion, Contor supported his large family by working as a store clerk. In 1941, the congregation had 65 member families and its own cemetery.

Wolfe and Dora Brody initially held Orthodox services at their home, and the peddlers and merchants returned from outlying areas every Friday to observe the Sabbath with the community. The group formally adopted the name of B’nai Zion in 1888 and rented a succession of halls and buildings for services. Mr. J. Friedman conducted services and also served as cantor and shochet. For a number of years the congregation rented a building at 1027 Carter Street which was destroyed by fire in the 1890s. One of the congregants, L. Slabosky, rushed into the roaring flames to save the Torah scrolls. He escaped from the building with the salvaged scrolls, but soon collapsed from the smoke and the heat and never fully recovered from the fire. The congregation bought land for a cemetery in 1890 after Mizpah Congregation stopped accepting non-member burials. By 1902 many of the members were financially stable, and contributed funds to build a large Romanesque synagogue at the corner of Fourteenth and Carter streets. Despite his own ties to the Reform congregation, Adolph Ochs assisted their efforts with a large contribution.

During this period, a second Orthodox congregation formed in the city. In 1904, a small group began meeting in a rented space on Poplar Street, before moving into a building shared with the Workman’s Circle. The congregation, Shaari-Zion, persisted for approximately 40 years, many of them under the leadership of lay Rabbi Herschel Contor. In addition to his role at Shaari Zion, Contor supported his large family by working as a store clerk. In 1941, the congregation had 65 member families and its own cemetery.

Congregations in the Early 20th Century

The Jewish congregations in Chattanooga grew steadily through the first decades of the 20th century. In 1904, Mizpah built a large new temple on Linsday and Oak Streets, but within a short time the congregation outgrew this building as well, reaching a membership of 153 by the close of World War I. In 1924, Adolph Ochs pledged funds for a new structure, in memory of his parents. Planning quickly commenced, and the Julius and Bertha Ochs Memorial Temple opened in 1928 on McCallie Avenue. By the 1920s, B’nai Zion members began to move away from the Carter Street neighborhood, and also began to look for a new structure closer to the congregant’s homes. After a successful fundraising initiative, the group built a new synagogue on Vine Street in 1931.

During this period, both congregations experienced relatively high turnover among spiritual leaders. Rabbi Julian Miller served at Mizpah from 1907 through 1919, and was succeeded by Rabbi Abraham Holzberg and Rabbi Samuel Shillman. A revolving retinue of rabbis led B’nai Zion for brief periods before the arrival of Rabbi Maisel, who led the congregation from 1921 through 1934.

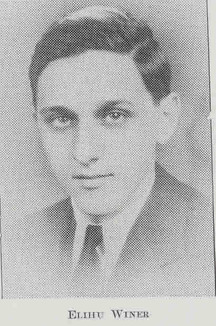

Relations between the two congregations were frosty on occasion, but the differences softened over time. Elihu Winer grew up in the B’nai Zion congregation in the 1920s, and studied at Vanderbilt and Yale before pursuing a career as a playwright and screenwriter. In an article for Opinion magazine, he recalls that: “for decades there existed a sharp cleavage between the two groups, with one clinging to a recently acquired tradition of emancipation and enlightenment, the other clinging just as tenaciously to the older tradition of the synagogue.” But as the Eastern European Jews advanced financially and acclimated to American society, the groups began to mingle and participate in shared social functions.

Elihu recounts that an internal generational and ideological debate complicated B’nai Zion’s 1931 move to Vine Street. He writes: “the urge to … be modern, up-to-date, was very strong and caused many defections from the ranks of orthodoxy. The old men of the shule held fast to their heritage, and refused to yield at all in matters of ritual … and continued to guide their actions as if the younger generations didn’t exist.” The desire to build a new synagogue in the 1920s was a conscious effort to modernize the congregation in some respects. The new synagogue was to be “a new building … in a nicer section of the city, a house of worship that would compare favorably with the Temple. Eventually the older men realized that something had to be done if the youngsters were to be held in line. They agreed to build a new shule.”

By the early 20th century, the Jewish community of Chattanooga supported a wide array of social clubs and activities. Early organizations included branches of B’nai Brith, Hadassah, he Chattanooga Farband, the Workman’s Circle, the YMHA (Young Men’s Hebrew Association), the Young Judea Club, Jewish Boy Scouts of America as well as men’s and women’s and children’s clubs affiliated with the congregations. By the early 1920s, Mizpah operated a Sunday School with 124 children. B’nai Zion organized a Religious School in 1934 with a beginning enrollment of 60 children.

Chattanoogan Harry Miller organized the Chattanooga Jewish Welfare Agency in 1931, supporting Jewish and public causes in Chattanooga and around the country. In 1938, the CJWA obtained a formal charter as the Chattanooga Jewish Federation. The Chattanooga Jewish Community Center was organized in 1944 and operated independently until merging with the Federation in 1993

The Jewish congregations in Chattanooga grew steadily through the first decades of the 20th century. In 1904, Mizpah built a large new temple on Linsday and Oak Streets, but within a short time the congregation outgrew this building as well, reaching a membership of 153 by the close of World War I. In 1924, Adolph Ochs pledged funds for a new structure, in memory of his parents. Planning quickly commenced, and the Julius and Bertha Ochs Memorial Temple opened in 1928 on McCallie Avenue. By the 1920s, B’nai Zion members began to move away from the Carter Street neighborhood, and also began to look for a new structure closer to the congregant’s homes. After a successful fundraising initiative, the group built a new synagogue on Vine Street in 1931.

During this period, both congregations experienced relatively high turnover among spiritual leaders. Rabbi Julian Miller served at Mizpah from 1907 through 1919, and was succeeded by Rabbi Abraham Holzberg and Rabbi Samuel Shillman. A revolving retinue of rabbis led B’nai Zion for brief periods before the arrival of Rabbi Maisel, who led the congregation from 1921 through 1934.

Relations between the two congregations were frosty on occasion, but the differences softened over time. Elihu Winer grew up in the B’nai Zion congregation in the 1920s, and studied at Vanderbilt and Yale before pursuing a career as a playwright and screenwriter. In an article for Opinion magazine, he recalls that: “for decades there existed a sharp cleavage between the two groups, with one clinging to a recently acquired tradition of emancipation and enlightenment, the other clinging just as tenaciously to the older tradition of the synagogue.” But as the Eastern European Jews advanced financially and acclimated to American society, the groups began to mingle and participate in shared social functions.

Elihu recounts that an internal generational and ideological debate complicated B’nai Zion’s 1931 move to Vine Street. He writes: “the urge to … be modern, up-to-date, was very strong and caused many defections from the ranks of orthodoxy. The old men of the shule held fast to their heritage, and refused to yield at all in matters of ritual … and continued to guide their actions as if the younger generations didn’t exist.” The desire to build a new synagogue in the 1920s was a conscious effort to modernize the congregation in some respects. The new synagogue was to be “a new building … in a nicer section of the city, a house of worship that would compare favorably with the Temple. Eventually the older men realized that something had to be done if the youngsters were to be held in line. They agreed to build a new shule.”

By the early 20th century, the Jewish community of Chattanooga supported a wide array of social clubs and activities. Early organizations included branches of B’nai Brith, Hadassah, he Chattanooga Farband, the Workman’s Circle, the YMHA (Young Men’s Hebrew Association), the Young Judea Club, Jewish Boy Scouts of America as well as men’s and women’s and children’s clubs affiliated with the congregations. By the early 1920s, Mizpah operated a Sunday School with 124 children. B’nai Zion organized a Religious School in 1934 with a beginning enrollment of 60 children.

Chattanoogan Harry Miller organized the Chattanooga Jewish Welfare Agency in 1931, supporting Jewish and public causes in Chattanooga and around the country. In 1938, the CJWA obtained a formal charter as the Chattanooga Jewish Federation. The Chattanooga Jewish Community Center was organized in 1944 and operated independently until merging with the Federation in 1993

Economic Growth

In the first half of the 20th century Chattanooga emerged as a major center for manufacturing and industry, earning the city the nickname “The Dynamo of Dixie.” Jewish residents played a central role in the city’s economic growth, engaging in a wide variety of industries and businesses. Some worked in retail, building many of Chattanooga’s largest stores. In 1920, Abe and Lou Effron opened a large clothing store that soon occupied a three-story building at the corner of Sixth and Market Streets. In 1921, Harry Miller, founder of the CJWA, opened The Vogue, a high-end ladies retail shop that operated for over half a century.

Others participated in the city’s thriving industries. In 1895, Robert Siskin and his wife Anna left their home in Lithuania, like many other immigrants, with no specific destination in mind. On the trip, a friend told him about opportunities in Chattanooga, and Siskin decided to travel with him to the area. Upon arrival, Siskin began working as a traveling peddler. He saved diligently, and in 1900 he and a partner opened a scrap metal business using $6 in startup capital and a rented lot. Siskin soon bought out his partner and renamed the business R.H. Siskin and Sons.

The business was modestly successful, and by 1910 the family still lived in a rented home and Robert still spent a good deal of time on the road seeking trade opportunities. Robert passed away in 1926, and left the business to his two sons Mose and Garrison, who successfully expanded the business. During World War II, the demand for scrap metal skyrocketed, and the Siskin operation grew. In 1949 the company moved beyond the scrap business, and began distributing new steel and other metal products. The company thrives today, and had net sales of over $159 million in 2003.

The Siskin brothers gave generously to the Chattanooga Jewish community and the general public. After recovering from a near fatal train accident in 1942, Garrison pledged to devote his substantial resources to helping others. The brothers established the Siskin Memorial Foundation in 1950, supporting a variety of local causes. In 1990, the foundation provided funding for Chattanooga’s Siskin Hospital for Physical Rehabilitation.

In the first half of the 20th century Chattanooga emerged as a major center for manufacturing and industry, earning the city the nickname “The Dynamo of Dixie.” Jewish residents played a central role in the city’s economic growth, engaging in a wide variety of industries and businesses. Some worked in retail, building many of Chattanooga’s largest stores. In 1920, Abe and Lou Effron opened a large clothing store that soon occupied a three-story building at the corner of Sixth and Market Streets. In 1921, Harry Miller, founder of the CJWA, opened The Vogue, a high-end ladies retail shop that operated for over half a century.

Others participated in the city’s thriving industries. In 1895, Robert Siskin and his wife Anna left their home in Lithuania, like many other immigrants, with no specific destination in mind. On the trip, a friend told him about opportunities in Chattanooga, and Siskin decided to travel with him to the area. Upon arrival, Siskin began working as a traveling peddler. He saved diligently, and in 1900 he and a partner opened a scrap metal business using $6 in startup capital and a rented lot. Siskin soon bought out his partner and renamed the business R.H. Siskin and Sons.

The business was modestly successful, and by 1910 the family still lived in a rented home and Robert still spent a good deal of time on the road seeking trade opportunities. Robert passed away in 1926, and left the business to his two sons Mose and Garrison, who successfully expanded the business. During World War II, the demand for scrap metal skyrocketed, and the Siskin operation grew. In 1949 the company moved beyond the scrap business, and began distributing new steel and other metal products. The company thrives today, and had net sales of over $159 million in 2003.

The Siskin brothers gave generously to the Chattanooga Jewish community and the general public. After recovering from a near fatal train accident in 1942, Garrison pledged to devote his substantial resources to helping others. The brothers established the Siskin Memorial Foundation in 1950, supporting a variety of local causes. In 1990, the foundation provided funding for Chattanooga’s Siskin Hospital for Physical Rehabilitation.

The Second Half of the 20th Century

Despite the continued success of businesses such as the Siskin’s, the city of Chattanooga as well as its Jewish community began to decline in the post-war years. From a peak of 3,800 in 1937, the Jewish population of Chattanooga slid over 40% to 2,200 by 1948. The loss of manufacturing jobs shrunk the city’s economic base while the growth of suburban centers diminished the city’s population. The very same mountains of such strategic importance in earlier times captured the smog from the city’s industries, and by 1969 the federal government determined Chattanooga’s air to be the dirtiest in the nation.

Although the population declined to some degree, the Chattanooga Jewish community maintained a critical population mass and continued to support a full range of communal activities in the most war years, and even found new opportunities for growth. In the early 1960s, members of B’nai Zion changed the congregation’s affiliation from Orthodox to Modern Conservative and joined the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism. The congregation also purchased an investment property on McBrien Road in Brainerd. After a number of years, the group built a new facility at the new site and moved in 1975. Mizpah Congregation continued to occupy the original 1928 Ochs building, albeit altered through the course of multiple renovations and additions.

Following B’nai Zion’s switch to Conservative Judaism, a small faction among the members decided to organize a separate Orthodox congregation. B’nai Zion member Morris Ellman led the organization of a new congregation named Beth Sholom. The group purchased a property on Pisgah Avenue in Brainerd. In 1977, the Beth Sholom building was bombed and completely destroyed by a notorious racist, anti-Semite, and psychopath. The perpetrator was later apprehended and convicted in the bombing and other assaults, including shooting a man outside of a St. Louis synagogue in 1977. The indomitable Beth Sholom members rebuilt the same year. While the congregation has shrunk in recent years, the members of Beth Sholom continue to worship regularly in their synagogue.

Despite the continued success of businesses such as the Siskin’s, the city of Chattanooga as well as its Jewish community began to decline in the post-war years. From a peak of 3,800 in 1937, the Jewish population of Chattanooga slid over 40% to 2,200 by 1948. The loss of manufacturing jobs shrunk the city’s economic base while the growth of suburban centers diminished the city’s population. The very same mountains of such strategic importance in earlier times captured the smog from the city’s industries, and by 1969 the federal government determined Chattanooga’s air to be the dirtiest in the nation.

Although the population declined to some degree, the Chattanooga Jewish community maintained a critical population mass and continued to support a full range of communal activities in the most war years, and even found new opportunities for growth. In the early 1960s, members of B’nai Zion changed the congregation’s affiliation from Orthodox to Modern Conservative and joined the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism. The congregation also purchased an investment property on McBrien Road in Brainerd. After a number of years, the group built a new facility at the new site and moved in 1975. Mizpah Congregation continued to occupy the original 1928 Ochs building, albeit altered through the course of multiple renovations and additions.

Following B’nai Zion’s switch to Conservative Judaism, a small faction among the members decided to organize a separate Orthodox congregation. B’nai Zion member Morris Ellman led the organization of a new congregation named Beth Sholom. The group purchased a property on Pisgah Avenue in Brainerd. In 1977, the Beth Sholom building was bombed and completely destroyed by a notorious racist, anti-Semite, and psychopath. The perpetrator was later apprehended and convicted in the bombing and other assaults, including shooting a man outside of a St. Louis synagogue in 1977. The indomitable Beth Sholom members rebuilt the same year. While the congregation has shrunk in recent years, the members of Beth Sholom continue to worship regularly in their synagogue.

The Jewish Community in Chattanooga Today

A 2000 study of the Chattanooga Jewish community estimated the population at around 1,400 members, a significant drop from its pre-World War II peak. Despite the diminished numbers, the remaining Jewish Chattanoogans continue to support a broad range of religious and communal functions. The city has embarked upon major revitalization campaigns aimed at improving the local environment and city infrastructure, and the Jewish residents of Chattanooga continue to play a vital role in the city’s economy and civic life.