Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Columbia, Tennessee

Columbia: Historical Overview

Located 45 miles south of Nashville, Columbia, Tennessee, has never been a center of Jewish life in the state. Yet, as in many other small towns across the South, a group of Jews lived in this seat of Maury County for over a century, though they failed to leave a permanent institutional mark on the community. In many ways, Columbia’s Jewish community was an offshoot of Nashville, which had a significant Jewish population and three synagogues. Jews moved back and forth between Columbia and the Tennessee capital city, and rather than build their own Jewish institutions, Columbia Jews supported those in Nashville.

Stories of the Jewish Community in Columbia

Early Jewish Residents

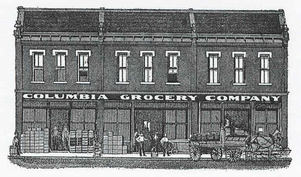

Though Columbia was founded in 1808, Jews did not settle in the area in significant numbers until after the Civil War. By one estimate, 81 Jews lived in Columbia by 1878. One of these was David Lazarus. Born in Prussia, Lazarus came to the United States as a boy in 1839. After living in Ohio, Lazarus moved to Pulaski, Tennessee, before he came to Columbia in 1875, where he opened a grocery store. In 1890, he moved his “Columbia Grocery Company” to a new, large two story building, and opened a wholesale operation that served other grocery stores in Maury and the surrounding counties. His sons Benjamin and Moses joined their father’s business. David became a respected local business leader, serving as a city alderman from 1888 to 1895 and again from 1898 to 1899.

Most of Columbia’s early Jewish settlers came from Eastern Europe. J. Rosenthal arrived in Columbia from Poland soon after the end of the Civil War. He spent two years peddling around the area, before opening a small dry goods store. Rosenthal remained in business in Columbia for several decades. As late as 1938, two of his children were still living in town. Isaac Barker was born in Russia, and came to Tennessee in 1871. By 1880, he was living in Columbia as a fruit salesman with his wife Sarah and their five children. Barker lived in Columbia until he died in the first decade of the 20th century. Isaac’s son, William, remained in Columbia and started a very successful egg and poultry company. In 1907, his business was earning over $200,000 a year, with a sizable portion of this total coming from selling eggs to merchants in Cuba. William Barker also sold “dressed poultry” and live chickens in the area around Columbia. Barker was active in civic life in Columbia, serving as the president of a local fraternal society, the colorfully named “Prudent Patricians of Pompeii.” Pinchas Garber left Poland in 1887, and lived in Pulaski and Lawrenceburg, Tennessee, before settling in Columbia with his wife Annie and five children by 1900. Garber opened a dry goods store, Garber & Co., which remained in business for almost 50 years.

Though Columbia was founded in 1808, Jews did not settle in the area in significant numbers until after the Civil War. By one estimate, 81 Jews lived in Columbia by 1878. One of these was David Lazarus. Born in Prussia, Lazarus came to the United States as a boy in 1839. After living in Ohio, Lazarus moved to Pulaski, Tennessee, before he came to Columbia in 1875, where he opened a grocery store. In 1890, he moved his “Columbia Grocery Company” to a new, large two story building, and opened a wholesale operation that served other grocery stores in Maury and the surrounding counties. His sons Benjamin and Moses joined their father’s business. David became a respected local business leader, serving as a city alderman from 1888 to 1895 and again from 1898 to 1899.

Most of Columbia’s early Jewish settlers came from Eastern Europe. J. Rosenthal arrived in Columbia from Poland soon after the end of the Civil War. He spent two years peddling around the area, before opening a small dry goods store. Rosenthal remained in business in Columbia for several decades. As late as 1938, two of his children were still living in town. Isaac Barker was born in Russia, and came to Tennessee in 1871. By 1880, he was living in Columbia as a fruit salesman with his wife Sarah and their five children. Barker lived in Columbia until he died in the first decade of the 20th century. Isaac’s son, William, remained in Columbia and started a very successful egg and poultry company. In 1907, his business was earning over $200,000 a year, with a sizable portion of this total coming from selling eggs to merchants in Cuba. William Barker also sold “dressed poultry” and live chickens in the area around Columbia. Barker was active in civic life in Columbia, serving as the president of a local fraternal society, the colorfully named “Prudent Patricians of Pompeii.” Pinchas Garber left Poland in 1887, and lived in Pulaski and Lawrenceburg, Tennessee, before settling in Columbia with his wife Annie and five children by 1900. Garber opened a dry goods store, Garber & Co., which remained in business for almost 50 years.

Organized Jewish Life in Columbia

Jews in Columbia had worshiped together informally since the late 19th century. Abraham Cheslar, who emigrated from Russia in 1885, and owned a furniture store and later a grocery store, served as the lay leader of the group. In 1908, they met for the High Holidays at the local Masonic Temple. They had not yet formed a congregation, and many Columbia Jews traveled north to Nashville for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. In fact, Cheslar’s son-in-law, Barney Smolinsky, was a board member of the Gay Street Synagogue in Nashville, and Pinchas Garber was a longtime member of the West End Synagogue.

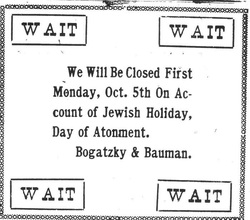

Columbia Jews had varying religious practices. The local newspaper reported in 1907 that some Jewish-owned stores in town would be closed one day for Rosh Hashanah while other stores would be closed the more traditional two days. Local stores would close on the High Holidays and run ads in the local newspaper informing their customers. These ads show how Columbia Jews maintained their religious practices, even without a formal congregation.

Finally, Columbia Jews organized a congregation sometime in the 1910’s, which they called Khal Kadosh (Holy Community). In 1919, it had 16 members and held weekly services in Hebrew and English. Khal Kadosh also had a religious school with 14 students. William Barker was the president while Abe Bauman was the secretary. In 1921, Julius Abrahams moved to Columbia from Nashville, and became a leader of the congregation. Abrahams led the services from the Reform prayer book. The group met on the second floor of Isaac Wolfe’s store. The congregation acquired a Torah and ark, although it never had a permanent building. In 1926, Abrahams moved back to Nashville, and the congregation seems to have dissolved in his absence. Since then, Columbia Jews have traveled to Nashville for religious services. Columbia never had a Jewish cemetery, as its Jews were usually buried in Nashville.

Jews in Columbia had worshiped together informally since the late 19th century. Abraham Cheslar, who emigrated from Russia in 1885, and owned a furniture store and later a grocery store, served as the lay leader of the group. In 1908, they met for the High Holidays at the local Masonic Temple. They had not yet formed a congregation, and many Columbia Jews traveled north to Nashville for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. In fact, Cheslar’s son-in-law, Barney Smolinsky, was a board member of the Gay Street Synagogue in Nashville, and Pinchas Garber was a longtime member of the West End Synagogue.

Columbia Jews had varying religious practices. The local newspaper reported in 1907 that some Jewish-owned stores in town would be closed one day for Rosh Hashanah while other stores would be closed the more traditional two days. Local stores would close on the High Holidays and run ads in the local newspaper informing their customers. These ads show how Columbia Jews maintained their religious practices, even without a formal congregation.

Finally, Columbia Jews organized a congregation sometime in the 1910’s, which they called Khal Kadosh (Holy Community). In 1919, it had 16 members and held weekly services in Hebrew and English. Khal Kadosh also had a religious school with 14 students. William Barker was the president while Abe Bauman was the secretary. In 1921, Julius Abrahams moved to Columbia from Nashville, and became a leader of the congregation. Abrahams led the services from the Reform prayer book. The group met on the second floor of Isaac Wolfe’s store. The congregation acquired a Torah and ark, although it never had a permanent building. In 1926, Abrahams moved back to Nashville, and the congregation seems to have dissolved in his absence. Since then, Columbia Jews have traveled to Nashville for religious services. Columbia never had a Jewish cemetery, as its Jews were usually buried in Nashville.

The Community Declines

By 1937, only 30 Jews lived in Columbia. Many of the merchants who owned dry goods or grocery stores in the early 20th century had moved away. Several of them, like William Barker, had moved to nearby Nashville. The Bauman family remained in town through the 1950s. Garber & Co. closed in 1948, and the last remaining member of the Garber family left Columbia around 1980. Other Jewish merchants had stores in Columbia after World War II. Joe Grossman owned a jewelry store, while Dave Gordon, Sam Kaufman, and Milton Feldman owned ladies clothing stores. But with Nashville only a short drive away on new and improved highways, there was little need to form Jewish institutions in town. As in many other Southern towns, these Jewish-owned stores eventually closed and their owners moved away.

By 1937, only 30 Jews lived in Columbia. Many of the merchants who owned dry goods or grocery stores in the early 20th century had moved away. Several of them, like William Barker, had moved to nearby Nashville. The Bauman family remained in town through the 1950s. Garber & Co. closed in 1948, and the last remaining member of the Garber family left Columbia around 1980. Other Jewish merchants had stores in Columbia after World War II. Joe Grossman owned a jewelry store, while Dave Gordon, Sam Kaufman, and Milton Feldman owned ladies clothing stores. But with Nashville only a short drive away on new and improved highways, there was little need to form Jewish institutions in town. As in many other Southern towns, these Jewish-owned stores eventually closed and their owners moved away.

The Jewish Community in Columbia Today

By 2007, only one Jew remained in Columbia. Gene Heller was born in Bessemer, Alabama, and moved to Columbia in 1961 to open a children's outerwear manufacturing company called “Weather Tamer.” Heller later sold the company to Gerber in 1983; by 1990, the factory had been closed. Heller went into real estate, buying apartment complexes and developing housing subdivisions in the area.

For all intents and purposes, a Jewish community no longer exists in Columbia. Because of the proximity to Nashville, there is no synagogue or cemetery than can attest to the once visible presence Jews had in Columbia.

For all intents and purposes, a Jewish community no longer exists in Columbia. Because of the proximity to Nashville, there is no synagogue or cemetery than can attest to the once visible presence Jews had in Columbia.