Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Clarksville, Tennessee

Clarksville: Historical Overview

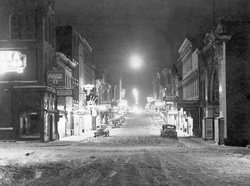

Nestled on the banks of the Cumberland River, Clarksville is located in the Ohio Valley, just 45 minutes north of Nashville. Founded in 1785 and named for the noted Revolutionary War hero George Rogers Clark, Clarksville was initially opened to settlement by veterans of George Washington’s Continental Army. The city grew in the early 19th century as it became linked to other cities through river boat traffic, improved roads, and eventually, in 1859, the railroad. Tobacco was the area’s main cash crop, and tobacco plantations sprouted along with an increasing number of slaves. Clarksville strongly supported secession, but was captured by the Union Army in 1862. Clarksville suffered a major blow in 1878 when fire swept through the city’s downtown, destroying 15 acres of property, including the county courthouse.

The Jewish population of Tennessee has always been concentrated in the state’s four largest cities. Nowhere is this more evident than in Clarksville, which is the state’s fifth largest and fastest growing city, but which has never had a significant Jewish population. In 2005, over 123,000 people lived in Clarksville, only a handful of which were Jews.

The Jewish population of Tennessee has always been concentrated in the state’s four largest cities. Nowhere is this more evident than in Clarksville, which is the state’s fifth largest and fastest growing city, but which has never had a significant Jewish population. In 2005, over 123,000 people lived in Clarksville, only a handful of which were Jews.

Stories of the Jewish Community in Clarksville

Early Jewish Residents

Jews first arrived in Clarksville in the years before the Civil War. David Kohn, a German-born immigrant, was a young merchant in Clarksville in 1860; Jacob Kline, only 17 years old, was a clerk in the Kohn’s store. By 1870, both men had moved away from Clarksville. William Rosenfield came to Clarksville after the Civil War, and opened a millinery shop by 1870. He and his wife Bertha had eight children, few if any of whom remained in Clarksville when they were adults. William Kleeman was one of the first Jews to settle in Clarksville permanently. Born in Bavaria in 1835, Kleeman came to the United States in 1852. After spending time in New York and Illinois, Kleeman moved with his family to Clarksville after the Civil War, where he opened a dry goods store. By 1880, he had closed the dry goods business and opened a butcher shop. His sons Ike, Arthur and Edward later joined him in the business. In the 20th century, the Kleemans became a very prominent family in town, though many of them converted to Christianity. William Kleeman, Ike's son, served as mayor of Clarksville in the 1950s; a local community center in Clarksville bears his name. Kleeman descendants still reside in Clarksville today.

Jews first arrived in Clarksville in the years before the Civil War. David Kohn, a German-born immigrant, was a young merchant in Clarksville in 1860; Jacob Kline, only 17 years old, was a clerk in the Kohn’s store. By 1870, both men had moved away from Clarksville. William Rosenfield came to Clarksville after the Civil War, and opened a millinery shop by 1870. He and his wife Bertha had eight children, few if any of whom remained in Clarksville when they were adults. William Kleeman was one of the first Jews to settle in Clarksville permanently. Born in Bavaria in 1835, Kleeman came to the United States in 1852. After spending time in New York and Illinois, Kleeman moved with his family to Clarksville after the Civil War, where he opened a dry goods store. By 1880, he had closed the dry goods business and opened a butcher shop. His sons Ike, Arthur and Edward later joined him in the business. In the 20th century, the Kleemans became a very prominent family in town, though many of them converted to Christianity. William Kleeman, Ike's son, served as mayor of Clarksville in the 1950s; a local community center in Clarksville bears his name. Kleeman descendants still reside in Clarksville today.

Eastern European Jews also made their way to Clarksville around the turn of the century. Russian-born Shyer Rubenstein came to America in 1894 and soon settled in Clarksville; he later opened a dry goods store with Isaac Schindler, who was born in Latvia. Shyer was later joined by other family members, including Morris and Charles Rubenstein, who also owned dry goods stores. Morris owned a store on Franklin Street called “The Famous.”

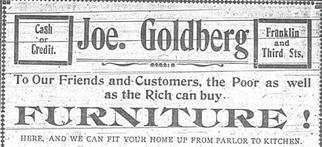

A cousin of the Rubenstein family, Joseph Goldberg, would leave a significant legacy in Clarksville. Born in Russia, Goldberg came to the United States in 1894, initially settling in Chicago. Around 1900, he moved to Clarksville to join his cousins; he started out peddling with merchandise from the Rubenstein & Schindler Dry Goods Store. Goldberg soon saved enough money to open a furniture store in Clarksville, though eventually he became infatuated with the new technology of motion pictures. Pursuing his passion,Goldberg built the Lillian Theater on Franklin Street in 1912. Described by the local newspaper as “one of the most elaborate and up-to-date movie houses in the South,” the theater burned down within its first year. Undaunted, Goldberg rebuilt the Lillian in 1914. Goldberg also bought the Majestic Theater and converted it to a live performance venue. He also constructed several buildings along what became known as the “Goldberg Block,” which he rented to merchants. Goldberg died in 1925, and management of the Lillian Theater was taken over by his son Ralph, who was forced the close the facility during the Great Depression. He sold it in 1939, when it was reopened as the Roxy Theater. When Joe died, the local newspaper praised him, writing that “few have contributed so substantially to Clarksville’s business development in the same time, and with a keener and truer interest in its welfare.” Goldberg’s descendants continued to live in Clarksville into the 21st century. Ralph’s son, William Goldberg, owned a store in town before he died in 2007.

A cousin of the Rubenstein family, Joseph Goldberg, would leave a significant legacy in Clarksville. Born in Russia, Goldberg came to the United States in 1894, initially settling in Chicago. Around 1900, he moved to Clarksville to join his cousins; he started out peddling with merchandise from the Rubenstein & Schindler Dry Goods Store. Goldberg soon saved enough money to open a furniture store in Clarksville, though eventually he became infatuated with the new technology of motion pictures. Pursuing his passion,Goldberg built the Lillian Theater on Franklin Street in 1912. Described by the local newspaper as “one of the most elaborate and up-to-date movie houses in the South,” the theater burned down within its first year. Undaunted, Goldberg rebuilt the Lillian in 1914. Goldberg also bought the Majestic Theater and converted it to a live performance venue. He also constructed several buildings along what became known as the “Goldberg Block,” which he rented to merchants. Goldberg died in 1925, and management of the Lillian Theater was taken over by his son Ralph, who was forced the close the facility during the Great Depression. He sold it in 1939, when it was reopened as the Roxy Theater. When Joe died, the local newspaper praised him, writing that “few have contributed so substantially to Clarksville’s business development in the same time, and with a keener and truer interest in its welfare.” Goldberg’s descendants continued to live in Clarksville into the 21st century. Ralph’s son, William Goldberg, owned a store in town before he died in 2007.

Organized Jewish Life in Clarksville

In the early 20th century, the small but growing Jewish community began to worship together. In 1906, they founded a congregation called B’nai Abraham (People of Abrham). Joseph Rosenfield was the president, J. Adler was treasurer, and Edward Kleeman was secretary. They originally met in the Knights of Pythias Hall, but later rented an old Disciples of Christ Church on Madison Street. B’nai Abraham did not have a rabbi, relying on lay reader Simon Katz to lead services. Occasionally, a rabbi from Nashville would come up to lead services. This early congregation was short-lived, disbanding in 1908. Even when they did not have a congregation, Clarksville Jews ran a religious school to teach their children about Judaism. In 1919, Maurice Latner and Ella Klein ran the Brandeis Sunday School in Clarksville.

In 1929, Clarksville Jews founded another congregation, which they named Beth El (House of God). In 1931, they dedicated two rented rooms on the second floor of the local Masonic Temple as their synagogue. Rabbi Michael Aaronson, who worked for the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, came down from Cincinnati to give the dedication address. About 75 people attended the dedication ceremony, including several Jews from small towns in southern Kentucky who joined the Clarksville congregation. Rabbi Aaronson, who had been blinded while fighting in World War I, also spoke to the local American Legion chapter during his visit to the city.

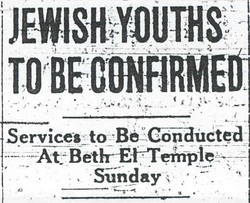

Beth El joined the Reform movement in 1931, and began to host student rabbis from Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati. In 1933, the congregation held its first confirmation ceremony. Student rabbi Eric Friedland officiated at the Sunday morning service in which four young men and women were confirmed. Although the congregation was nominally Reform, most members came from Orthodox backgrounds and their worship style was a mixture of the two. When services were lay-led, they were more Orthodox; when student rabbis came to lead services, they were Reform. Beth El also held social events, such as the 1933 congregational picnic held at Kleeman’s Farm, which attracted 100 people from Clarksville and such Kentucky towns as Hopkinsville, Russellville, Bowling Green, and Greenville to eat what the newspaper reported as a “delectable chicken barbecue dinner.” Indeed, Beth El was a regional congregation.

The congregation reached a peak of activity when it hired Rabbi Alfred Vise as its spiritual leader in 1939. Vise was a German refugee who had fled the country after his synagogue in Hamburg was destroyed by the Nazis during Kristallnacht. Congregation Ohavai Sholom of Nashville helped to bring Rabbi Vise over and helped pay his salary while he was in Clarksville. Rabbi Vise served the small congregation for five years, before leaving to take a pulpit in Blytheville, Arkansas. Without Vise’s leadership, and facing declining membership numbers, Beth El disbanded in the late 1940s.

In the early 20th century, the small but growing Jewish community began to worship together. In 1906, they founded a congregation called B’nai Abraham (People of Abrham). Joseph Rosenfield was the president, J. Adler was treasurer, and Edward Kleeman was secretary. They originally met in the Knights of Pythias Hall, but later rented an old Disciples of Christ Church on Madison Street. B’nai Abraham did not have a rabbi, relying on lay reader Simon Katz to lead services. Occasionally, a rabbi from Nashville would come up to lead services. This early congregation was short-lived, disbanding in 1908. Even when they did not have a congregation, Clarksville Jews ran a religious school to teach their children about Judaism. In 1919, Maurice Latner and Ella Klein ran the Brandeis Sunday School in Clarksville.

In 1929, Clarksville Jews founded another congregation, which they named Beth El (House of God). In 1931, they dedicated two rented rooms on the second floor of the local Masonic Temple as their synagogue. Rabbi Michael Aaronson, who worked for the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, came down from Cincinnati to give the dedication address. About 75 people attended the dedication ceremony, including several Jews from small towns in southern Kentucky who joined the Clarksville congregation. Rabbi Aaronson, who had been blinded while fighting in World War I, also spoke to the local American Legion chapter during his visit to the city.

Beth El joined the Reform movement in 1931, and began to host student rabbis from Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati. In 1933, the congregation held its first confirmation ceremony. Student rabbi Eric Friedland officiated at the Sunday morning service in which four young men and women were confirmed. Although the congregation was nominally Reform, most members came from Orthodox backgrounds and their worship style was a mixture of the two. When services were lay-led, they were more Orthodox; when student rabbis came to lead services, they were Reform. Beth El also held social events, such as the 1933 congregational picnic held at Kleeman’s Farm, which attracted 100 people from Clarksville and such Kentucky towns as Hopkinsville, Russellville, Bowling Green, and Greenville to eat what the newspaper reported as a “delectable chicken barbecue dinner.” Indeed, Beth El was a regional congregation.

The congregation reached a peak of activity when it hired Rabbi Alfred Vise as its spiritual leader in 1939. Vise was a German refugee who had fled the country after his synagogue in Hamburg was destroyed by the Nazis during Kristallnacht. Congregation Ohavai Sholom of Nashville helped to bring Rabbi Vise over and helped pay his salary while he was in Clarksville. Rabbi Vise served the small congregation for five years, before leaving to take a pulpit in Blytheville, Arkansas. Without Vise’s leadership, and facing declining membership numbers, Beth El disbanded in the late 1940s.

The Community Declines

The Jewish community of Clarksville was never large. According to a 1937 population survey, 55 Jews lived in the city. In 1940, Beth El had only 19 contributing members, while renting a sanctuary that seated 100 people. By 1945, its membership had dropped sharply to 12 households. Most of its members were Russian-born merchants who owned clothing or furniture stores on Franklin Street downtown. Many of the families were related to each other, tracing their roots back to Latvia. Many of the children raised in Clarksville, like Joseph Cohen, moved to larger cities to find greater career opportunities; Cohen became a professor of English at Tulane University in New Orleans and founded the school’s Jewish Studies program.

Many moved to nearby Nashville, and with the construction of the interstate highway connecting the two cities, it became easier for Clarksville Jews to attend religious services in the capital city. Indeed, Clarksville Jews had long been connected to Nashville’s Jewish community, with Nashville rabbis conducting funerals in Clarksville, and Clarksville Jews being buried in Nashville’s Jewish cemeteries.

The Jewish community of Clarksville was never large. According to a 1937 population survey, 55 Jews lived in the city. In 1940, Beth El had only 19 contributing members, while renting a sanctuary that seated 100 people. By 1945, its membership had dropped sharply to 12 households. Most of its members were Russian-born merchants who owned clothing or furniture stores on Franklin Street downtown. Many of the families were related to each other, tracing their roots back to Latvia. Many of the children raised in Clarksville, like Joseph Cohen, moved to larger cities to find greater career opportunities; Cohen became a professor of English at Tulane University in New Orleans and founded the school’s Jewish Studies program.

Many moved to nearby Nashville, and with the construction of the interstate highway connecting the two cities, it became easier for Clarksville Jews to attend religious services in the capital city. Indeed, Clarksville Jews had long been connected to Nashville’s Jewish community, with Nashville rabbis conducting funerals in Clarksville, and Clarksville Jews being buried in Nashville’s Jewish cemeteries.

The Jewish Community in Clarksville Today

Since World War II, Clarksville has grown tremendously. In 1942, the U.S. Army built Fort Campbell just ten miles north of Clarksville in southern Kentucky. The base is currently the home of the 101st Airborne Division and about 28,000 military personnel. The growth of Fort Campbell has led to a boom in Clarksville, which is now the fastest growing city in the state. In 1960, 22,000 people lived in Clarksville; by 2000, over 100,000 did. 2005 estimates put the population at around 125,000.

Usually, a booming economy and a rising population go hand-in-hand with a growing Jewish community, but this is not the case in Clarksville. Its Jewish population is extremely small, consisting of only a handful of families. The reason for this seeming anomaly is likely rooted in recent large scale changes in Southern Jewish life. Historically, Southern Jews were concentrated in retail trade, and thrived in areas where the economy was booming. But Clarksville’s growth has occurred during a period in which the Jewish store owner has largely disappeared. The sons and daughters of shopkeepers have gone to college, become professionals, and moved away to larger cities. There aren’t enough Jewish store owners to take advantage of the economic opportunities in Clarksville. Indeed, those Jews who do live in the city are likely either professors at Austin Peay State University or doctors at the growing regional medical center. If this growth had occurred 50 to 100 years earlier, Clarksville would have likely emerged as a large and active Jewish community.

Despite their small numbers and lack of Jewish institutions, Jews have left their mark on Clarksville. From the Roxy Theater, which was rebuilt in 1947 after another fire, to the Harriet Cohn Guidance Center, which was donated by Jessel and Harriet Cohn to help those with mental health needs, Jews have been an important part of life in Clarksville for well over a century.

Usually, a booming economy and a rising population go hand-in-hand with a growing Jewish community, but this is not the case in Clarksville. Its Jewish population is extremely small, consisting of only a handful of families. The reason for this seeming anomaly is likely rooted in recent large scale changes in Southern Jewish life. Historically, Southern Jews were concentrated in retail trade, and thrived in areas where the economy was booming. But Clarksville’s growth has occurred during a period in which the Jewish store owner has largely disappeared. The sons and daughters of shopkeepers have gone to college, become professionals, and moved away to larger cities. There aren’t enough Jewish store owners to take advantage of the economic opportunities in Clarksville. Indeed, those Jews who do live in the city are likely either professors at Austin Peay State University or doctors at the growing regional medical center. If this growth had occurred 50 to 100 years earlier, Clarksville would have likely emerged as a large and active Jewish community.

Despite their small numbers and lack of Jewish institutions, Jews have left their mark on Clarksville. From the Roxy Theater, which was rebuilt in 1947 after another fire, to the Harriet Cohn Guidance Center, which was donated by Jessel and Harriet Cohn to help those with mental health needs, Jews have been an important part of life in Clarksville for well over a century.