Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Goldsboro, North Carolina

Overview >> North Carolina >> Goldsboro

Goldsboro: Historical Overview

Goldsboro, formerly known as Waynesborough, blossomed in the 1840s. The Wilmington and Weldon Railroad was completed and a hotel was built at its intersection with New Bern Road, creating the perfect place for merchants to set up shop. More and more people came to this growing village, eventually named “Goldsborough’s Junction” after Major Matthew T. Goldsborough of the railroad company. By the time the town was incorporated in 1847, the name was shortened to Goldsborough and it had a population of about 100 residents.

Stories of the Jewish Community in Goldsboro

Rabbi Julius Mayerberg

Rabbi Julius Mayerberg

Asher Edwards

Among the early Jewish settlers of Goldsboro was Asher Edwards, who had originally been named Urbansky. He got his new name after he had been peddling with a French immigrant named Eduard. The Frenchman eventually got tired of the peddling life, but, since the peddler’s license was in Eduard’s name, Urbansky changed his own. During the Civil War, Edwards smuggled quinine, the first effective treatment for malaria, to the Confederacy. He later brought his brothers, Lipman and Joseph, to the United States. They too adopted the name “Edwards” and all ran a clothing store together.

Organized Jewish Life in Goldsboro

There is not much information about the Jews of Goldsboro prior to the organization of the congregation, but there is no doubt that they were practicing their religious traditions. In 1875, they founded a burial society and purchased land for a cemetery from the town of Goldsboro; N. Schultz, R.M. Cohn, and Joseph Ballenberger were the trustees of the society. Soon after, a Ladies Hebrew Assistance Society was founded. By the time Goldsboro Jews founded an official congregation, they already had a Torah.

In 1883, 33 Goldsboro Jews gathered at the Odd Fellows Hall and formally established Congregation Oheb Sholom (Lovers of Peace) for the purpose of building a synagogue. They chose their name in honor of the synagogue of the same name in Baltimore, from which many of the congregants had come. The cantor of the Baltimore congregation, Dr. Alois Kaiser, who is considered the founder of the American cantorate, gave a speech at this first meeting of the Goldsboro congregation. Adolph Lehman was named the president of the fledgling group. The members decided to follow the same worship style practiced by Oheb Sholom in Baltimore. According to the new congregation’s bylaws, the Sabbath and Jewish holidays were to be governed by “Biblical injunction, rather than by expediency” and the divine services were to be in Hebrew exclusively. The rules also stated that men had to wear a yarmulke (skullcap) during services. While they demonstrated some Reform leanings by establishing a mixed-gender choir, the congregation maintained a more conservative form of practice by using the Minhag Jastrow prayer book. It was not until 1913 that Oheb Sholom finally adopted the Reform Union Prayer Book.

Almost two-thirds of Oheb Sholom’s founding members were German-speaking immigrants, with roughly an even split between Bavaria and Prussia as their native country. Yet a significant minority, 35%, were native born, with most from North Carolina. Those who were born in the U.S. were more likely to be young; indeed, several were the teenaged sons of other founding members. The average age of the founders was 34 years. Most of these founders were involved in retail trade. 55% of them were listed as merchants in the 1880 census, while 32% were store clerks. Three were peddlers, while one was a farmer and another a butcher. Most merchants, like the Weil brothers, sold general dry goods, although a few had specialty stores. Ike Fuchtler and Alfred Kern ran a furniture store together in Goldsboro, while Sam Cohn and his son Leopold ran a meat market.

Soon after forming, the congregation leased the second floor of the armory building from H. Weil & Brothers for use as a temporary synagogue. The Ladies’ Assistance Society provided furnishings for the space. The congregation soon organized both a religious school and a Jewish day school. Oheb Sholom elected the Rev. I.M. Bloch to serve as service leader, Hebrew teacher, and shochet (kosher butcher), though Bloch only remained in Goldsboro for six months before moving to take a position in Petersburg, Virginia. In October of 1883, the congregation purchased a lot and began a campaign to raise money to build a synagogue. One event that raised a significant amount was a lecture given by Simon Wolf, a Jewish leader from Washington, D.C. Along with these funds and various pledges, they were able to begin construction.

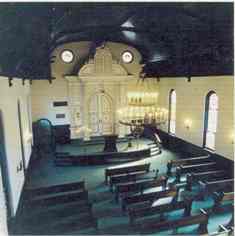

Despite these efforts, the congregation struggled at times during its early years, sometimes resorting to interest-bearing loans from members. Nevertheless, the synagogue was completed in December of 1886, becoming only the second Jewish house of worship in the state of North Carolina. It was officially dedicated on December 31. Alois Kaiser of Oheb Sholom in Baltimore and Simon Wolf returned to Goldsboro for the dedication and the banquet ball that followed.

In July of 1890, the congregation hired Rabbi Julius H. Mayerberg, who would serve the congregation for 34 years. Mayerburg, who had emigrated from Germany in 1871, led the congregation as it gradually embraced Reform Judaism. In 1890, after a period of prolonged discussion, the congregation voted to join the Union of American Hebrew Congregations. Despite their allegiance to this Reform organization, their worship was more traditional. In 1913, they started using the Reform Union Prayer Book and introduced English into the Shabbat service. The following year, the congregation purchased an organ. In 1915, after a bequest from the late Sol Weil, the congregation had an annex built that housed the religious school and meetings of the B’nai B’rith, Sisterhood, and Hadassah.

Among the early Jewish settlers of Goldsboro was Asher Edwards, who had originally been named Urbansky. He got his new name after he had been peddling with a French immigrant named Eduard. The Frenchman eventually got tired of the peddling life, but, since the peddler’s license was in Eduard’s name, Urbansky changed his own. During the Civil War, Edwards smuggled quinine, the first effective treatment for malaria, to the Confederacy. He later brought his brothers, Lipman and Joseph, to the United States. They too adopted the name “Edwards” and all ran a clothing store together.

Organized Jewish Life in Goldsboro

There is not much information about the Jews of Goldsboro prior to the organization of the congregation, but there is no doubt that they were practicing their religious traditions. In 1875, they founded a burial society and purchased land for a cemetery from the town of Goldsboro; N. Schultz, R.M. Cohn, and Joseph Ballenberger were the trustees of the society. Soon after, a Ladies Hebrew Assistance Society was founded. By the time Goldsboro Jews founded an official congregation, they already had a Torah.

In 1883, 33 Goldsboro Jews gathered at the Odd Fellows Hall and formally established Congregation Oheb Sholom (Lovers of Peace) for the purpose of building a synagogue. They chose their name in honor of the synagogue of the same name in Baltimore, from which many of the congregants had come. The cantor of the Baltimore congregation, Dr. Alois Kaiser, who is considered the founder of the American cantorate, gave a speech at this first meeting of the Goldsboro congregation. Adolph Lehman was named the president of the fledgling group. The members decided to follow the same worship style practiced by Oheb Sholom in Baltimore. According to the new congregation’s bylaws, the Sabbath and Jewish holidays were to be governed by “Biblical injunction, rather than by expediency” and the divine services were to be in Hebrew exclusively. The rules also stated that men had to wear a yarmulke (skullcap) during services. While they demonstrated some Reform leanings by establishing a mixed-gender choir, the congregation maintained a more conservative form of practice by using the Minhag Jastrow prayer book. It was not until 1913 that Oheb Sholom finally adopted the Reform Union Prayer Book.

Almost two-thirds of Oheb Sholom’s founding members were German-speaking immigrants, with roughly an even split between Bavaria and Prussia as their native country. Yet a significant minority, 35%, were native born, with most from North Carolina. Those who were born in the U.S. were more likely to be young; indeed, several were the teenaged sons of other founding members. The average age of the founders was 34 years. Most of these founders were involved in retail trade. 55% of them were listed as merchants in the 1880 census, while 32% were store clerks. Three were peddlers, while one was a farmer and another a butcher. Most merchants, like the Weil brothers, sold general dry goods, although a few had specialty stores. Ike Fuchtler and Alfred Kern ran a furniture store together in Goldsboro, while Sam Cohn and his son Leopold ran a meat market.

Soon after forming, the congregation leased the second floor of the armory building from H. Weil & Brothers for use as a temporary synagogue. The Ladies’ Assistance Society provided furnishings for the space. The congregation soon organized both a religious school and a Jewish day school. Oheb Sholom elected the Rev. I.M. Bloch to serve as service leader, Hebrew teacher, and shochet (kosher butcher), though Bloch only remained in Goldsboro for six months before moving to take a position in Petersburg, Virginia. In October of 1883, the congregation purchased a lot and began a campaign to raise money to build a synagogue. One event that raised a significant amount was a lecture given by Simon Wolf, a Jewish leader from Washington, D.C. Along with these funds and various pledges, they were able to begin construction.

Despite these efforts, the congregation struggled at times during its early years, sometimes resorting to interest-bearing loans from members. Nevertheless, the synagogue was completed in December of 1886, becoming only the second Jewish house of worship in the state of North Carolina. It was officially dedicated on December 31. Alois Kaiser of Oheb Sholom in Baltimore and Simon Wolf returned to Goldsboro for the dedication and the banquet ball that followed.

In July of 1890, the congregation hired Rabbi Julius H. Mayerberg, who would serve the congregation for 34 years. Mayerburg, who had emigrated from Germany in 1871, led the congregation as it gradually embraced Reform Judaism. In 1890, after a period of prolonged discussion, the congregation voted to join the Union of American Hebrew Congregations. Despite their allegiance to this Reform organization, their worship was more traditional. In 1913, they started using the Reform Union Prayer Book and introduced English into the Shabbat service. The following year, the congregation purchased an organ. In 1915, after a bequest from the late Sol Weil, the congregation had an annex built that housed the religious school and meetings of the B’nai B’rith, Sisterhood, and Hadassah.

Photo courtesy of the North Carolina State Archives

Photo courtesy of the North Carolina State Archives

The Weil Family

The new temple annex was only one of many significant contributions of the Weil family to Goldsboro and its Jewish community. Herman was the first of the Weil brothers to come to Goldsboro, North Carolina. He had immigrated to the United States in 1858 when he was 16 years old. Initially, he lived in Baltimore with his sisters but soon moved to Goldsboro, where he worked as a clerk in Henry Oettinger’s store. When the Civil War began, Herman was among the first to Join Captain J. B. Whitaker’s company of Goldsboro volunteers, in spite of his limited ability to speak English. Henry Weil, who was four years younger than Herman, was the second of the brothers to come to Goldsboro. After the war, Henry and Herman went into business for themselves in June of 1865, opening up their own store in the same location that Henry Oettinger’s store had been. In 1866, Solomon Weil, who was 17 at the time, joined his brothers in Goldsboro.

H. Weil & Bros. was located in the heart of Goldsboro’s downtown, right across from the railroad tracks. The store soon became a commercial trading center for eastern North Carolina, drawing in customers from the surrounding areas. They eventually started a wholesale operation that supplied stores throughout the Carolinas. The retail store was successful, and the brothers soon built a new two-story brick building to house the growing business. The bricks for the building came from a brickyard also owned by the Weils. The store sold a wide array of goods, from groceries, clothing, hats, and shoes to bricks, coal, and lumber.

Soon, H. Weil & Bros. became a prominent part of the business establishment. Not only did they begin dealing in real estate, but Herman Weil became an incorporator of the Building and Loan Association in Goldsboro in 1873. They were involved in several different enterprises, including the Goldsboro Ice Company, the Carolina Rice Mills, the Goldsboro Oil Company, the Pioneer Tobacco Company, the Goldsboro Savings Bank, and the Goldsboro Storage and Warehouse Company. The Weil brothers were very involved in civic affairs in Goldsboro. In 1881, Solomon Weil was elected alderman. The brothers also helped establish the town’s public school system. In 1890, Solomon and Henry Weil donated land to the city of Goldsboro for Herman Park, named for their brother Herman Weil.

The new temple annex was only one of many significant contributions of the Weil family to Goldsboro and its Jewish community. Herman was the first of the Weil brothers to come to Goldsboro, North Carolina. He had immigrated to the United States in 1858 when he was 16 years old. Initially, he lived in Baltimore with his sisters but soon moved to Goldsboro, where he worked as a clerk in Henry Oettinger’s store. When the Civil War began, Herman was among the first to Join Captain J. B. Whitaker’s company of Goldsboro volunteers, in spite of his limited ability to speak English. Henry Weil, who was four years younger than Herman, was the second of the brothers to come to Goldsboro. After the war, Henry and Herman went into business for themselves in June of 1865, opening up their own store in the same location that Henry Oettinger’s store had been. In 1866, Solomon Weil, who was 17 at the time, joined his brothers in Goldsboro.

H. Weil & Bros. was located in the heart of Goldsboro’s downtown, right across from the railroad tracks. The store soon became a commercial trading center for eastern North Carolina, drawing in customers from the surrounding areas. They eventually started a wholesale operation that supplied stores throughout the Carolinas. The retail store was successful, and the brothers soon built a new two-story brick building to house the growing business. The bricks for the building came from a brickyard also owned by the Weils. The store sold a wide array of goods, from groceries, clothing, hats, and shoes to bricks, coal, and lumber.

Soon, H. Weil & Bros. became a prominent part of the business establishment. Not only did they begin dealing in real estate, but Herman Weil became an incorporator of the Building and Loan Association in Goldsboro in 1873. They were involved in several different enterprises, including the Goldsboro Ice Company, the Carolina Rice Mills, the Goldsboro Oil Company, the Pioneer Tobacco Company, the Goldsboro Savings Bank, and the Goldsboro Storage and Warehouse Company. The Weil brothers were very involved in civic affairs in Goldsboro. In 1881, Solomon Weil was elected alderman. The brothers also helped establish the town’s public school system. In 1890, Solomon and Henry Weil donated land to the city of Goldsboro for Herman Park, named for their brother Herman Weil.

This civic involvement continued through the next generation. Gertrude, Henry Weil’s daughter, was born in Goldsboro in 1879. After attending the Horace Mann School and Smith College in the northeast, Gertrude became a staunch suffragist and returned to Goldsboro determined to make a difference in her home community. She became very involved in Oheb Sholom’s religious school, serving as a teacher for at least 35 years. Gertrude was especially active in the North Carolina Association of Jewish Women, which was founded in 1921. Gertrude served on the group’s board her entire life and even served as its president twice. Under her leadership, the NCAJW conducted a census of adult Jews and helped establish the Hillel Foundation at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Early on, Weil was among the minority of Reform Jews in favor of the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine. Gertrude and her mother Mina became close with Henrietta Szold, who later founded Hadassah, the women’s Zionist organization; Szold even visited the Weil home in Goldsboro. The Weil women participated in Hadassah locally and regionally. Both Gertrude and her parents visited Palestine and continued to donate money to Zionist causes.

Gertrude Weil’s civic involvement went beyond the Jewish community. She was active in the Goldsboro Woman’s Club, which had been established by her mother in 1899, and the North Carolina Federation of Women’s Clubs. Yet her primary focus was women’s voting rights. It began in 1912 when she mounted a successful crusade to allow women to sit on local school boards, even though they could not yet vote for them. Two years later, she helped establish the Goldsboro Equal Suffrage Association and traveled around the state with national leaders, such as Carrie Chapman Catt, to gain support for a constitutional amendment granting women the right to vote. By 1919, she was president of the North Carolina Equal Suffrage League. She vigorously lobbied the state legislature to adopt the 19th amendment, but North Carolina failed to ratify it. Despite this local setback, the amendment was finally ratified nationally in 1920. Soon after, Weil established the North Carolina League of Women Voters to make sure that the women in her state would understand and use their new right. In 1922, Weil made news when she destroyed stacks of pre-marked ballots meant to be used for illegal ballot stuffing.

Weil did not retreat from the political sphere after gaining the right to vote. She became very involved in the issues of child and women’s labor and the right to unionize. She supported striking female textile workers in 1929. Finally, in 1931, Weil’s activism helped win shorter hours for female workers, the prohibition of night work, and many other industrial reforms. In 1933, she was put in charge of administering local relief efforts when she was appointed Director of Federal Public Relief Work during the New Deal.

Weil’s commitment to social justice even extended to the difficult Southern issue of race. In 1930, she joined the Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching. Two years later, the Governor of North Carolina appointed Gertrude to the North Carolina Commission on Interracial Cooperation, which worked to improve race relations in the state. Gertrude advocated integration of the schools and continued to live in downtown Goldsboro long after most white families had left the area, often inviting her black neighbors into her home for social occasions.

Early on, Weil was among the minority of Reform Jews in favor of the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine. Gertrude and her mother Mina became close with Henrietta Szold, who later founded Hadassah, the women’s Zionist organization; Szold even visited the Weil home in Goldsboro. The Weil women participated in Hadassah locally and regionally. Both Gertrude and her parents visited Palestine and continued to donate money to Zionist causes.

Gertrude Weil’s civic involvement went beyond the Jewish community. She was active in the Goldsboro Woman’s Club, which had been established by her mother in 1899, and the North Carolina Federation of Women’s Clubs. Yet her primary focus was women’s voting rights. It began in 1912 when she mounted a successful crusade to allow women to sit on local school boards, even though they could not yet vote for them. Two years later, she helped establish the Goldsboro Equal Suffrage Association and traveled around the state with national leaders, such as Carrie Chapman Catt, to gain support for a constitutional amendment granting women the right to vote. By 1919, she was president of the North Carolina Equal Suffrage League. She vigorously lobbied the state legislature to adopt the 19th amendment, but North Carolina failed to ratify it. Despite this local setback, the amendment was finally ratified nationally in 1920. Soon after, Weil established the North Carolina League of Women Voters to make sure that the women in her state would understand and use their new right. In 1922, Weil made news when she destroyed stacks of pre-marked ballots meant to be used for illegal ballot stuffing.

Weil did not retreat from the political sphere after gaining the right to vote. She became very involved in the issues of child and women’s labor and the right to unionize. She supported striking female textile workers in 1929. Finally, in 1931, Weil’s activism helped win shorter hours for female workers, the prohibition of night work, and many other industrial reforms. In 1933, she was put in charge of administering local relief efforts when she was appointed Director of Federal Public Relief Work during the New Deal.

Weil’s commitment to social justice even extended to the difficult Southern issue of race. In 1930, she joined the Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching. Two years later, the Governor of North Carolina appointed Gertrude to the North Carolina Commission on Interracial Cooperation, which worked to improve race relations in the state. Gertrude advocated integration of the schools and continued to live in downtown Goldsboro long after most white families had left the area, often inviting her black neighbors into her home for social occasions.

Lionel Weil

Lionel Weil

Gertrude Weil’s impact on her community did not pass unnoticed. In 1951, the Chi Omega Sorority named her Outstanding Woman of the year. The following year, the North Carolina Woman’s College (later the University of North Carolina at Greensboro) presented her with an honorary doctorate of Humane Letters. Her alma mater, Smith College, awarded her the Smith Medal in 1964 in recognition of a “lifetime of service to the cultural, charitable, religious, and political welfare of [her] State.” In 1955, at Weil’s invitation, Eleanor Roosevelt visited Goldsboro and gave a speech at Oheb Sholom.

Gertrude’s cousin Lionel Weil became an important business leader in Goldsboro. He started in the family’s wholesale business but eventually got involved with their fertilizer factory. He served as a city alderman from 1904 to 1922. He spent many years on the local school board. When the banking crisis of 1932-33 struck Goldsboro, Lionel helped design a new banking system for the county. In recognition of his service, he was made president of the holding corporation of the Bank of Wayne. He was involved in several local and statewide boards, including the State Farm Debt Adjustment Commission, the county Agricultural Adjustment Act board, and the Tobacco Advisory Commission. He also served as director of the State Forestry Association, the National Fertilizer Association, and the State Plant Food Institute. Between Lionel, Gertrude, and other members of the family, the Weils had a profound impact on Goldsboro.

Gertrude’s cousin Lionel Weil became an important business leader in Goldsboro. He started in the family’s wholesale business but eventually got involved with their fertilizer factory. He served as a city alderman from 1904 to 1922. He spent many years on the local school board. When the banking crisis of 1932-33 struck Goldsboro, Lionel helped design a new banking system for the county. In recognition of his service, he was made president of the holding corporation of the Bank of Wayne. He was involved in several local and statewide boards, including the State Farm Debt Adjustment Commission, the county Agricultural Adjustment Act board, and the Tobacco Advisory Commission. He also served as director of the State Forestry Association, the National Fertilizer Association, and the State Plant Food Institute. Between Lionel, Gertrude, and other members of the family, the Weils had a profound impact on Goldsboro.

Oheb Sholom

Oheb Sholom

Prominent Jews of Goldsboro

William Heilig and Max Meyers also made their mark on Goldsboro and other small towns across the South. Both left Russia in 1909, settling in Goldsboro by 1911. They started out peddling to the farmers in the countryside outside of Goldsboro, sometimes even carrying furniture on their backs. In 1913, they opened a furniture store together in Goldsboro. The business grew steadily, surviving the Great Depression with only one year in the red. By 1939, the partners had opened branch stores in Kinston, Wilson, Raleigh, and Rocky Mount, North Carolina. After World War II, the chain expanded, focusing on small towns and cities of less than 50,000 residents. After a string of acquisitions in the 1980s, Heilig-Meyers became the largest publicly traded furniture retail company in the United States. By 1995, Heilig-Meyers had 662 stores in 24 states.

Morris Leder was another prominent Jewish immigrant who found retail success in Goldsboro. After arriving in the U.S. from Poland in 1922, Leder began to open clothing stores with his brother Herman throughout North Carolina. Within a few decades, they oversaw 25 retail operations across the region, and Morris decided to permanently settle in Goldsboro with his wife Minnie. In addition to serving as a retail pioneer in Goldsboro, Morris Leder led the community in social and civic organizations such as the Kiwanis Club and Shriners. In the 1950s, he chaired the United Jewish Appeal Israeli Bond Drive in Goldsboro. In 1964, Leder was elected president of the state-wide B’nai B’rith Association. At the same time, even well into his 80s, Morris rarely missed a day of work at his store in Goldsboro, which he consciously chose to keep downtown even as many of his customers relocated to the suburbs.

William Heilig and Max Meyers also made their mark on Goldsboro and other small towns across the South. Both left Russia in 1909, settling in Goldsboro by 1911. They started out peddling to the farmers in the countryside outside of Goldsboro, sometimes even carrying furniture on their backs. In 1913, they opened a furniture store together in Goldsboro. The business grew steadily, surviving the Great Depression with only one year in the red. By 1939, the partners had opened branch stores in Kinston, Wilson, Raleigh, and Rocky Mount, North Carolina. After World War II, the chain expanded, focusing on small towns and cities of less than 50,000 residents. After a string of acquisitions in the 1980s, Heilig-Meyers became the largest publicly traded furniture retail company in the United States. By 1995, Heilig-Meyers had 662 stores in 24 states.

Morris Leder was another prominent Jewish immigrant who found retail success in Goldsboro. After arriving in the U.S. from Poland in 1922, Leder began to open clothing stores with his brother Herman throughout North Carolina. Within a few decades, they oversaw 25 retail operations across the region, and Morris decided to permanently settle in Goldsboro with his wife Minnie. In addition to serving as a retail pioneer in Goldsboro, Morris Leder led the community in social and civic organizations such as the Kiwanis Club and Shriners. In the 1950s, he chaired the United Jewish Appeal Israeli Bond Drive in Goldsboro. In 1964, Leder was elected president of the state-wide B’nai B’rith Association. At the same time, even well into his 80s, Morris rarely missed a day of work at his store in Goldsboro, which he consciously chose to keep downtown even as many of his customers relocated to the suburbs.

Photo courtesy of Julian Preisler

Photo courtesy of Julian Preisler

Oheb Sholom in the 20th Century

While the Jewish community of Goldsboro was never very large, Oheb Sholom remained an active congregation. In 1924, Rabbi Abe Shindling replaced Rabbi Mayerberg. The congregation only had 31 families at the time, but the financial success of several members enabled the small group to afford a full-time spiritual leader, although it did not prevent a high degree of turnover in the position. In 1931, Rabbi Iser Freund succeeded Shingling. Five years later, Freund left and was replaced by Rabbi Joseph Weiss. By 1937, 143 Jews lived in Goldsboro.

During World War II, temple members were active in the war effort. Seventeen members of the congregation served in the military during the war. From 1940 to 1945, the Temple was open on Saturday evenings and Sundays for the soldiers stationed nearby at Seymour Johnson Air Force Base. The servicemen would play ping-pong, darts, and other games while congregants served them sandwiches and snacks. Herman Levin, a representative of the Jewish Welfare Board, came to Goldsboro and helped to organize the local USO and other activities, such as seders, for the soldiers.

After the war, Oheb Sholom continued to employ full-time rabbis. Among those who led the congregation were Jerome Tolochko, Maurice Feuer, Solomon Herbst, I. J. Sarasohn, and Tibor Fabian. Rabbi Fabian, who retired in the 1970s, was the last full-time rabbi to grace the pulpit of Oheb Sholom. After that, a circuit-riding rabbi would visit the congregation periodically, and they would bring down student rabbis from Hebrew Union College. Since the early 1990s, Oheb Sholom has not had a regular rabbinic presence.

While the Jewish community of Goldsboro was never very large, Oheb Sholom remained an active congregation. In 1924, Rabbi Abe Shindling replaced Rabbi Mayerberg. The congregation only had 31 families at the time, but the financial success of several members enabled the small group to afford a full-time spiritual leader, although it did not prevent a high degree of turnover in the position. In 1931, Rabbi Iser Freund succeeded Shingling. Five years later, Freund left and was replaced by Rabbi Joseph Weiss. By 1937, 143 Jews lived in Goldsboro.

During World War II, temple members were active in the war effort. Seventeen members of the congregation served in the military during the war. From 1940 to 1945, the Temple was open on Saturday evenings and Sundays for the soldiers stationed nearby at Seymour Johnson Air Force Base. The servicemen would play ping-pong, darts, and other games while congregants served them sandwiches and snacks. Herman Levin, a representative of the Jewish Welfare Board, came to Goldsboro and helped to organize the local USO and other activities, such as seders, for the soldiers.

After the war, Oheb Sholom continued to employ full-time rabbis. Among those who led the congregation were Jerome Tolochko, Maurice Feuer, Solomon Herbst, I. J. Sarasohn, and Tibor Fabian. Rabbi Fabian, who retired in the 1970s, was the last full-time rabbi to grace the pulpit of Oheb Sholom. After that, a circuit-riding rabbi would visit the congregation periodically, and they would bring down student rabbis from Hebrew Union College. Since the early 1990s, Oheb Sholom has not had a regular rabbinic presence.

The Jewish Community in Goldsboro Today

Over the last several decades, Goldsboro’s Jewish community has experienced a decline in numbers. Children raised in the town have moved to bigger cities in search of greater economic opportunity. There has not been a religious school at Oheb Sholom since the 1970s. Most Goldsboro Jews joined larger synagogues in nearby cities, and Temple Oheb Sholom was used only for occasional services and life cycle events. In recent years, the congregation has become inactive and the synagogue rented out to an Episcopal Church for use as a food pantry.