Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Statesville, North Carolina

Overview >> North Carolina >> Statesville

Statesville: Historical Overview

Statesville, North Carolina, first attracted permanent European settlers in the 1750s, as Scots-Irish and German immigrants moved to what was then called Fourth Creek Congregation. In 1788, the state legislature named this frontier outpost in the North Carolina piedmont the seat of newly formed Iredell County. Statesville remained a small settlement until the arrival of the railroad in 1858 and the town’s rise as a center of tobacco growing and processing. Thanks to two Jewish immigrants from Germany, Statesville also became a major business distribution center for various roots and herbs in the late 19th century.

Stories of the Jewish Community in Statesville

Wallace Bros. Botanical Co.

Wallace Bros. Botanical Co.

The Wallace Brothers

David and Isaac Wallach left their home in Hessen-Cassel in the 1850s. David came first, in 1851, and settled in Smoaks, South Carolina. Isaac followed in 1854. After the Panic of 1857, Isaac Wallach and his brother-in-law Lewis Elias, moved to Statesville, which had just been named the terminal of the Western North Carolina Railroad; they opened a general merchandise store in collaboration with a third partner, Jacob Rintels. After Elias and Rintels left the business, David Wallach joined his brother in the business in Statesville. The store suffered during the Civil War, and the two brothers, who had changed their name to Wallace, even moved to Charleston for a short time. By 1868, they had returned to Statesville, where their store began to flourish. By 1870, the partners owned $10,000 of personal estate. By 1876, their operation was the largest in the northwest corner of the state.

In addition to general merchandise, the brothers also bought and sold medicinal herbs, which soon grew into a major operation. In 1871, they hired Mordecai Hyams, a Charleston Jew who was an expert in roots, barks, and herbs, to be their botanical manager and built a two-story warehouse to store the product. Hyams established ties with rural farmers and merchants around the state who would ship the herbs they had found to Statesville in return for other goods. Hyams scoured the countryside looking for new herbs to sell. After five years, Hyams had expanded their line of herbal products to 2,300 items. Hyams gained national attention and acclaim for his work. By 1876, their herb operation was doing over $50,000 in business, as herb gathering kept many rural North Carolinians afloat during the economic panic of the 1870s. By the late 1880s, their sales volume had surpassed $100,000 a year. The Wallace brothers eventually closed their retail store, focusing their efforts on their booming wholesale herb business, which had customers around the country and in Europe. The Wallace Brothers Company went bankrupt in 1895, though David’s son William was able to buy up the remaining stock with the help of outside investors. He reopened the business, which remained in operation until 1950.

David and Isaac Wallach left their home in Hessen-Cassel in the 1850s. David came first, in 1851, and settled in Smoaks, South Carolina. Isaac followed in 1854. After the Panic of 1857, Isaac Wallach and his brother-in-law Lewis Elias, moved to Statesville, which had just been named the terminal of the Western North Carolina Railroad; they opened a general merchandise store in collaboration with a third partner, Jacob Rintels. After Elias and Rintels left the business, David Wallach joined his brother in the business in Statesville. The store suffered during the Civil War, and the two brothers, who had changed their name to Wallace, even moved to Charleston for a short time. By 1868, they had returned to Statesville, where their store began to flourish. By 1870, the partners owned $10,000 of personal estate. By 1876, their operation was the largest in the northwest corner of the state.

In addition to general merchandise, the brothers also bought and sold medicinal herbs, which soon grew into a major operation. In 1871, they hired Mordecai Hyams, a Charleston Jew who was an expert in roots, barks, and herbs, to be their botanical manager and built a two-story warehouse to store the product. Hyams established ties with rural farmers and merchants around the state who would ship the herbs they had found to Statesville in return for other goods. Hyams scoured the countryside looking for new herbs to sell. After five years, Hyams had expanded their line of herbal products to 2,300 items. Hyams gained national attention and acclaim for his work. By 1876, their herb operation was doing over $50,000 in business, as herb gathering kept many rural North Carolinians afloat during the economic panic of the 1870s. By the late 1880s, their sales volume had surpassed $100,000 a year. The Wallace brothers eventually closed their retail store, focusing their efforts on their booming wholesale herb business, which had customers around the country and in Europe. The Wallace Brothers Company went bankrupt in 1895, though David’s son William was able to buy up the remaining stock with the help of outside investors. He reopened the business, which remained in operation until 1950.

Early Settlers

The Wallace brothers had a significant impact on Statesville and its Jewish community. Isaac and David used the proceeds from their highly successful herb business to invest in other ventures, including the purchase and renovation of the Cooper Hotel, a local cotton mill, and creation of a suburban housing development south of the city. They also helped bring other Jews to town, many of whom started out working for the Wallace brothers before opening businesses of their own. Julius Lowenstein, related to the brothers by marriage, became a successful liquor wholesaler in Statesville. In 1879, Jacob Hoffman moved to town from Bamberg, South Carolina; he initially worked for the Wallace brothers before opening his own dry goods store. Abraham Moses, a cousin of the Wallaces, worked for them before starting his own dry goods and millinery store. Other Jews moved to Statesville in the late 19th century, with many opening wholesale businesses. Louis Pinkus opened his own herb business, while Henry Clarke and W.M. Meyer opened a wholesale liquor business together that thrived until North Carolina banned alcohol sales in 1903. Benjamin Ash came to Statesville from New York and opened a wholesale tobacco operation. Others, like John Stephany, who owned the Baltimore Clothing House, went into retail trade

The Wallace brothers had a significant impact on Statesville and its Jewish community. Isaac and David used the proceeds from their highly successful herb business to invest in other ventures, including the purchase and renovation of the Cooper Hotel, a local cotton mill, and creation of a suburban housing development south of the city. They also helped bring other Jews to town, many of whom started out working for the Wallace brothers before opening businesses of their own. Julius Lowenstein, related to the brothers by marriage, became a successful liquor wholesaler in Statesville. In 1879, Jacob Hoffman moved to town from Bamberg, South Carolina; he initially worked for the Wallace brothers before opening his own dry goods store. Abraham Moses, a cousin of the Wallaces, worked for them before starting his own dry goods and millinery store. Other Jews moved to Statesville in the late 19th century, with many opening wholesale businesses. Louis Pinkus opened his own herb business, while Henry Clarke and W.M. Meyer opened a wholesale liquor business together that thrived until North Carolina banned alcohol sales in 1903. Benjamin Ash came to Statesville from New York and opened a wholesale tobacco operation. Others, like John Stephany, who owned the Baltimore Clothing House, went into retail trade

Photo courtesy of Julian Preisler

Photo courtesy of Julian Preisler

Organized Jewish Life in Statesville

In 1883, this growing Jewish community gathered together in the home of Isaac Wallace and formally established Congregation Emanuel. Benjamin Ash was elected the first president and initially served as lay leader during services. Ash had earlier led informal High Holiday services. At its founding, Congregation Emanuel had 34 adult members from 15 different households. During High Holiday services in 1883, Jews came to Statesville from such nearby towns as Hickory and Salisbury. The group soon met at the local Fireman’s Hall and hired Rabbi Jacob Mayerberger as their rabbi. Though not originally affiliated with the Reform Union of American Hebrew Congregations, Congregation Emanuel was Reform in worship style. Its bylaws called for members to act “in a quiet and becoming manner” during services and stated, “during the recitation of those prayers which are exclusively for the minister, the Congregation must maintain perfect silence. No one is permitted to anticipate or chime in with the minister or choir.” Yet, a motion to remove head coverings during services was voted down by the board in 1900. Eight years later, the congregation voted to adopt the Reform Union Prayer Book, make head coverings optional, and affiliate with the UAHC, the national organization of Reform Judaism.

Congregation Emanuel moved quickly to build a synagogue. Thanks to the financial support of the Wallace family, by 1891, the congregation bought land, and a year later dedicated Statesville’s first permanent Jewish house of worship. Rabbi Benjamin Szold of Baltimore was the featured speaker at the dedication. Rabbi S. Tyor led Congregation Emanuel at the time it moved into its brick Romanesque revival synagogue. A year earlier, the congregation had acquired land in Oakwood Cemetery for a Jewish burial ground. In 1899, after a tornado destroyed the local Reformed Presbyterian Church, Congregation Emanuel invited them to meet in their synagogue for over a year until the church was rebuilt. A few years later, the congregation built a parsonage for their rabbi on a lot adjacent to the temple, although Congregation Emanuel soon lost its full-time spiritual leader, relying on students from Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati to lead High Holiday services from 1906 to 1920.

In 1883, this growing Jewish community gathered together in the home of Isaac Wallace and formally established Congregation Emanuel. Benjamin Ash was elected the first president and initially served as lay leader during services. Ash had earlier led informal High Holiday services. At its founding, Congregation Emanuel had 34 adult members from 15 different households. During High Holiday services in 1883, Jews came to Statesville from such nearby towns as Hickory and Salisbury. The group soon met at the local Fireman’s Hall and hired Rabbi Jacob Mayerberger as their rabbi. Though not originally affiliated with the Reform Union of American Hebrew Congregations, Congregation Emanuel was Reform in worship style. Its bylaws called for members to act “in a quiet and becoming manner” during services and stated, “during the recitation of those prayers which are exclusively for the minister, the Congregation must maintain perfect silence. No one is permitted to anticipate or chime in with the minister or choir.” Yet, a motion to remove head coverings during services was voted down by the board in 1900. Eight years later, the congregation voted to adopt the Reform Union Prayer Book, make head coverings optional, and affiliate with the UAHC, the national organization of Reform Judaism.

Congregation Emanuel moved quickly to build a synagogue. Thanks to the financial support of the Wallace family, by 1891, the congregation bought land, and a year later dedicated Statesville’s first permanent Jewish house of worship. Rabbi Benjamin Szold of Baltimore was the featured speaker at the dedication. Rabbi S. Tyor led Congregation Emanuel at the time it moved into its brick Romanesque revival synagogue. A year earlier, the congregation had acquired land in Oakwood Cemetery for a Jewish burial ground. In 1899, after a tornado destroyed the local Reformed Presbyterian Church, Congregation Emanuel invited them to meet in their synagogue for over a year until the church was rebuilt. A few years later, the congregation built a parsonage for their rabbi on a lot adjacent to the temple, although Congregation Emanuel soon lost its full-time spiritual leader, relying on students from Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati to lead High Holiday services from 1906 to 1920.

William Wallace

William Wallace

Community Decline

The Jewish community of Statesville, while never large, went into decline in the early 20th century. By 1907, Congregation Emanuel had only 12 members, while 59 total Jews lived in Statesville. By 1927, only 40 Jews remained, consisting of only about six families. Many of the early Jewish settlers moved away, especially after alcohol prohibition killed the local liquor industry, and newly arriving Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe largely bypassed Statesville. In a 1909 report about the local Jewish community sent to the Industrial Removal Office in New York, William Wallace wrote that “we have had few Russians and Roumanians. They do not remain long, but go elsewhere where there are folks of their own kind.” Due to this population decline, the congregation stopped holding services and became dormant. The remaining Jews in Statesville traveled to other towns in the area for religious services. The synagogue building was preserved and occasionally rented out to various church groups. The parsonage was also rented out, with the proceeds going to support the Federated Fund for Jewish Charities overseen by Dr. Wallace Hoffman. The congregation lent its Torahs to Hillel at the University of North Carolina and to a congregation in Fredericksburg, Virginia.

Although the Jewish community declined in Statesville, a few new Jewish arrivals still found economic opportunity in the town. Louis Gordon, whose parents had emigrated from Lithuania, moved to Statesville from High Point in 1917, and began selling scrap metal and furniture. Often he would pick up scrap items from his furniture customers after delivering their purchases. Louis and his wife Charlotte had five sons, but giving them a Jewish education was a challenge after the synagogue became defunct. When it came time for their bar mitzvah, each of the boys would spend a year in High Point staying with their grandparents and going to Sunday school. All five of Louis Gordon’s sons went into the family business, taking over the operation after their father died in 1954. Two sons took over the furniture store while the other three ran the scrap metal business. In 2009, the fifth generation of Gordon family members was running the scrap operation.

The Wallace family continued to leave their mark on Statesville well into the 20th century. William Wallace, son of David and Amelia, founded the Statesville Cotton Mill, and served as its president for forty years. He helped to found the local public school system and served on the school board for many years. Through his work with the Statesville Development Company, Wallace helped to bring new industry to the city. His son John became a lawyer who served as president of the Statesville Chamber of Commerce in 1937. John Wallace was elected to the North Carolina State Senate in 1940. Four years later, he became president of the Statesville Cotton Mill.

By 1951, Congregation Emanuel had only three member families. While they had not held services in their synagogue for years, the congregation was still a legal entity with elected officers. Sig Wallace served as secretary from 1903 until his death in 1941, after which Wallace Hoffman took his place.

The Jewish community of Statesville, while never large, went into decline in the early 20th century. By 1907, Congregation Emanuel had only 12 members, while 59 total Jews lived in Statesville. By 1927, only 40 Jews remained, consisting of only about six families. Many of the early Jewish settlers moved away, especially after alcohol prohibition killed the local liquor industry, and newly arriving Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe largely bypassed Statesville. In a 1909 report about the local Jewish community sent to the Industrial Removal Office in New York, William Wallace wrote that “we have had few Russians and Roumanians. They do not remain long, but go elsewhere where there are folks of their own kind.” Due to this population decline, the congregation stopped holding services and became dormant. The remaining Jews in Statesville traveled to other towns in the area for religious services. The synagogue building was preserved and occasionally rented out to various church groups. The parsonage was also rented out, with the proceeds going to support the Federated Fund for Jewish Charities overseen by Dr. Wallace Hoffman. The congregation lent its Torahs to Hillel at the University of North Carolina and to a congregation in Fredericksburg, Virginia.

Although the Jewish community declined in Statesville, a few new Jewish arrivals still found economic opportunity in the town. Louis Gordon, whose parents had emigrated from Lithuania, moved to Statesville from High Point in 1917, and began selling scrap metal and furniture. Often he would pick up scrap items from his furniture customers after delivering their purchases. Louis and his wife Charlotte had five sons, but giving them a Jewish education was a challenge after the synagogue became defunct. When it came time for their bar mitzvah, each of the boys would spend a year in High Point staying with their grandparents and going to Sunday school. All five of Louis Gordon’s sons went into the family business, taking over the operation after their father died in 1954. Two sons took over the furniture store while the other three ran the scrap metal business. In 2009, the fifth generation of Gordon family members was running the scrap operation.

The Wallace family continued to leave their mark on Statesville well into the 20th century. William Wallace, son of David and Amelia, founded the Statesville Cotton Mill, and served as its president for forty years. He helped to found the local public school system and served on the school board for many years. Through his work with the Statesville Development Company, Wallace helped to bring new industry to the city. His son John became a lawyer who served as president of the Statesville Chamber of Commerce in 1937. John Wallace was elected to the North Carolina State Senate in 1940. Four years later, he became president of the Statesville Cotton Mill.

By 1951, Congregation Emanuel had only three member families. While they had not held services in their synagogue for years, the congregation was still a legal entity with elected officers. Sig Wallace served as secretary from 1903 until his death in 1941, after which Wallace Hoffman took his place.

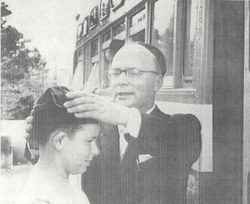

Circuit-Riding Rabbi Harold Friedman

Circuit-Riding Rabbi Harold Friedman

Community Growth

The 1950s saw a resurgence in the Statesville Jewish community as a growing number of Jews moved to the area. Statesville was experiencing an industrial boom, and a handful of new Jewish families moved to the area to operate textile factories or open stores in the wake of this increased economic activity. Isadore and Albert Schneider opened a textile mill in nearby Taylorsville and moved to Statesville in 1951. Joseph and Sally Jay moved to Statesville around the same time, establishing a blouse manufacturing business. Max and Florence Lerner opened a clothing store in Taylorsville by 1951.

This growing number of Jews decided to revive Congregation Emanuel. I.D. Blumenthal of Charlotte, the president of the North Carolina Association of Jewish Men, encouraged the group to reform and made a significant financial contribution to help repair and reopen the synagogue. In October, 1953, Statesville Jews gathered at the home of Milton Steinberger to reorganize the congregation. A few months later, the group decided to spend $2,000 fixing the temple so it could be used again. Among the leaders at this time were Julius and Viola Aaronson. Julius was the first president of the reactivated congregation and Viola—a descendant of Isaac Wallace—helped to clean out the neglected synagogue building to make it usable again. As the congregation renewed its activities members founded a Ladies Auxiliary and a religious school and the congregation instituted weekly Friday night services. Blumenthal created an itinerant rabbi program that served Statesville and several other small congregations in the Carolinas. For the High Holidays of 1954, Rabbi Harold Friedman, the circuit-rider who was featured in Life magazine, led services for 65 people at the newly reopened synagogue. Rabbi Friedman chose to live in Statesville during his tenure as a circuit-riding rabbi. The congregation also hosted student rabbis from Hebrew Union College during the early and mid-1950s, although this practice ceased when they affiliated with the Conservative movement later in the decade.

In 1957, the congregation, which had 27 families, held a dedication for a new addition that included a social hall and space for classrooms. Ten years later, they built a new education wing that housed the growing religious school. In 1968-69, Congregation Emanuel had four b’nei mitzvah, the most it ever had during a year. Yet the congregation was still too small to employ a full-time rabbi, and tore down the old parsonage to create a much needed parking lot.

The 1950s saw a resurgence in the Statesville Jewish community as a growing number of Jews moved to the area. Statesville was experiencing an industrial boom, and a handful of new Jewish families moved to the area to operate textile factories or open stores in the wake of this increased economic activity. Isadore and Albert Schneider opened a textile mill in nearby Taylorsville and moved to Statesville in 1951. Joseph and Sally Jay moved to Statesville around the same time, establishing a blouse manufacturing business. Max and Florence Lerner opened a clothing store in Taylorsville by 1951.

This growing number of Jews decided to revive Congregation Emanuel. I.D. Blumenthal of Charlotte, the president of the North Carolina Association of Jewish Men, encouraged the group to reform and made a significant financial contribution to help repair and reopen the synagogue. In October, 1953, Statesville Jews gathered at the home of Milton Steinberger to reorganize the congregation. A few months later, the group decided to spend $2,000 fixing the temple so it could be used again. Among the leaders at this time were Julius and Viola Aaronson. Julius was the first president of the reactivated congregation and Viola—a descendant of Isaac Wallace—helped to clean out the neglected synagogue building to make it usable again. As the congregation renewed its activities members founded a Ladies Auxiliary and a religious school and the congregation instituted weekly Friday night services. Blumenthal created an itinerant rabbi program that served Statesville and several other small congregations in the Carolinas. For the High Holidays of 1954, Rabbi Harold Friedman, the circuit-rider who was featured in Life magazine, led services for 65 people at the newly reopened synagogue. Rabbi Friedman chose to live in Statesville during his tenure as a circuit-riding rabbi. The congregation also hosted student rabbis from Hebrew Union College during the early and mid-1950s, although this practice ceased when they affiliated with the Conservative movement later in the decade.

In 1957, the congregation, which had 27 families, held a dedication for a new addition that included a social hall and space for classrooms. Ten years later, they built a new education wing that housed the growing religious school. In 1968-69, Congregation Emanuel had four b’nei mitzvah, the most it ever had during a year. Yet the congregation was still too small to employ a full-time rabbi, and tore down the old parsonage to create a much needed parking lot.

The Jewish Community in Statesville Today

In the early 1990s, the growing number of Jews in the Lake Norman area bolstered Congregation Emanuel and its religious school, though Lake Norman Jews have recently established two congregations of their own. Congregation Emanuel no longer has a religious school; families with children now send them to Lake Norman or Winston-Salem for religious instruction. Emanuel is affiliated with the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism through its relationship with Temple Israel in Charlotte. Today, Congregation Emanuel continues to worship in its 1892 synagogue. In recent decades, the congregation has remained at about 35 families, even as its members have aged and children raised in Statesville have moved to larger cities in search of greater economic and social opportunities. In 2008, the congregation became part of a pilot program with the Conservative Jewish Theological Seminary in New York, in which rabbinic student Aaron Philmus traveled to Statesville regularly to lead services. Though the congregation is not growing, it remains active. Thus, over 125 years after its founding, Congregation Emanuel continues to serve as a home for Statesville’s small but vibrant Jewish community.